Traumatic Grief Treatment: A Pilot Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effects of a treatment program targeting debilitating grief symptoms were tested in a pilot study. METHOD: Twenty-one individuals experiencing traumatic grief were recruited for participation, and 13 completed the full 4-month protocol. The treatment protocol used imaginal re-living of the death, in vivo exposure to avoided activities and situations, and interpersonal therapy. RESULTS: Significant improvement in grief symptoms and associated anxiety and depression was observed for both completer and intent-to-treat groups. CONCLUSIONS: The traumatic grief treatment protocol appears to be a promising intervention for debilitating grief.

Pathological grief has been described in the literature (1–3), but criteria for identifying a clinically significant condition involving grief were unavailable until the development of the Inventory of Complicated Grief (4). Individuals who score >25 on this scale endorse a constellation of symptoms, including preoccupation with the deceased, longing, yearning, disbelief and inability to accept the death, bitterness or anger about the death, and avoidance of reminders of the loss. This condition, called traumatic grief (5), has been associated with impairment and poor outcomes (6).

To our knowledge, no studies of the treatment of traumatic grief have been reported. Reports of the treatment of pathological grief from different therapeutic schools exist. However, pathological grief comprises heterogeneous symptoms, and most authors do not operationalize what is meant by this condition. Most treatment includes some form of regrief or guided mourning. Two behavioral studies of guided mourning (7, 8) are of particular interest. These two well-conducted trials from the same laboratory compared exposure to avoided reminders of the death with antiexposure instructions and showed some advantage for exposure. The investigators did not systematically use imaginal reliving. Pathological grief was not operationally defined, and outcome was measured with a variety of instruments.

Studies of bereavement-related depression conducted by our group have included individuals with high Inventory of Complicated Grief scores. In these studies, depressive symptoms responded well to standard treatment. However, neither antidepressant medication nor interpersonal psychotherapy relieved grief symptoms (9). We therefore undertook a treatment development project targeting traumatic grief. The results of pilot study of a new treatment for this condition are reported here.

Method

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Eligible subjects were at least 3 months postloss and scored >25 on the Inventory of Complicated Grief (4). All subjects were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV by experienced, certified raters. The subjects completed the Inventory of Complicated Grief, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the Beck Depression Inventory at weekly therapy sessions.

We treated 21 subjects with a mean age of 51.4 years (SD=15.8, range=22–71). The mean time since the death associated with traumatic grief was 2.9 years (range=3 months to 9 years). The subjects’ mean number of current DSM-IV axis I diagnoses was 1.7, including major depression in nine and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in seven subjects. For all subjects, grief symptoms were prominent and considered the primary clinical problem.

Eight subjects dropped out after one or more sessions (mean number of sessions=5.75, SD=3.37, median=7, range=1–10). Dropouts were significantly younger than completers (39.4 years versus 58.8 years) (t=–3.37, df=19, p=0.003). More dropouts were grieving violent deaths, including two by murder, one by suicide, and two by accidents. Thirteen subjects (nine women and four men) completed a full 4-month course of treatment.

Traumatic grief treatment incorporates strategies from interpersonal therapy for depression (10) and cognitive behavior therapy for PTSD (11). The goals of traumatic grief treatment include reducing the intensity of grief, facilitating the ability to enjoy fond memories of the deceased, and supporting reengagement in daily activities and relationships with others. The treatment is guided by a manual, available from the first author, and was designed to be delivered in approximately 16 sessions over 4 months. The primary strategy for grief reduction is exposure, both imaginal (reexperiencing the death scene) and in vivo, targeting situations the bereaved patient is avoiding. Interpersonal therapy methods are used to help patients reengage in relationships with others.

In the pilot study, history taking included a detailed account of the death, as well as a chronicle of the relationship with the deceased and a review of current relationships. The symptoms of traumatic grief were described, along with the rationale for the treatment. Avoidance was identified, and in vivo exposure exercises were planned. Mindfulness breathing was taught. The therapists explained the Subjective Units of Distress Scale, a standard procedure used to assess discomfort during exposure. Situations and/or cues that triggered avoidance were arranged in a hierarchical order, according to discomfort level.

During audiotaped reexperiencing sessions, the patient was asked to describe the death, as if it were happening in the present, with eyes closed, while paying attention to feelings evoked. The therapist provided support and helped to identify periods of most intense emotion (“hot spots”). Daily homework included listening to the audiotape of imaginal exposure and doing in vivo exposure exercises. Toward the end of treatment, progress was reviewed to ensure that the subject could have access to comforting memories and that social isolation was addressed. A few patients wrote farewell letters.

The Wilcoxon paired rank-sum test was used to compare completers and noncompleters on all measures. For pre- to posttreatment analyses of symptoms, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed. Within-group effect sizes were computed to correspond with each signed-rank test, using the mean difference divided by the standard deviation of the difference.

Results

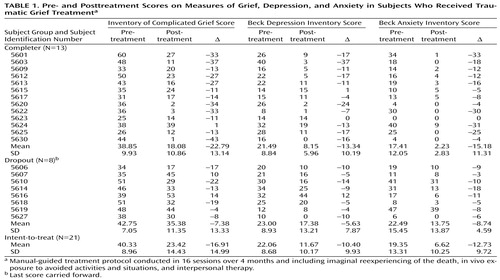

Significant and very large pretreatment–posttreatment differences were found for Inventory of Complicated Grief scores in both the completer group (N=13) (mean=22.79, SD=13.14, z=–3.11, p=0.002) and the intent-to-treat group (N=21) (mean=16.91, SD=14.99, z=–3.51, p<0.001) (Table 1). These results comprised large effect sizes of 2.19 and 1.45, respectively. In the intent-to-treat group, the mean decrease in the Inventory of Complicated Grief score was nearly twice that observed in our prior study of depressed patients whose scores were consistent with traumatic grief and who received interpersonal therapy only (mean=–8.75, SD=14.1) (9). Among completers this difference was even more striking. It is noteworthy that the completer group resembled closely the patients who participated in the bereavement-related depression study (9). All but three of the subjects in the completer group were over 60 years of age, and one was 56. Eight were spousally bereaved.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression, as measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory, respectively, showed similar marked reductions for both the completer and the intent-to-treat groups (anxiety in completers: z=–3.06, p=0.002; anxiety in intent-to-treat group: z=–3.92, p<0.001; depression in completers: z=–2.98, p=0.003; depression in intent-to-treat group: z=–3.44, p=0.001). Again, results comprised large effect sizes of 2.04 and 1.08, respectively, for the Beck Anxiety Inventory and of 1.80 and 1.16, respectively, for the Beck Depression Inventory.

Discussion

We report promising results for a pilot series of patients in a treatment development project targeting traumatic grief, a clinical entity that appears to be prevalent and debilitating. The results of the traumatic grief treatment protocol were substantially better than that of interpersonal therapy alone in similar subjects. Several patients who participated in this study had already received interpersonal therapy and/or other psychotherapy with little effect. A randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm the efficacy of the traumatic grief treatment approach. Such a study is currently underway at our clinic. We present these results to draw attention to the need for treatment targeting debilitating grief symptoms and to provide information about strategies that may be effective.

|

Presented in part at the 152nd annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., May 15–20, 1999. Received June 22, 2000; revision received Jan. 5, 2001; accepted March 1, 2001. From the Anxiety Disorders Prevention Program and the Centers for Mid-Life and Late-Life Mood and Anxiety Disorders, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic; and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Shear, Anxiety Disorders Clinic, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213-2593; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-53817 and Intervention Center grants MH-52247, MH-30915, MH-00295, MH-37869, and MH-43832. The authors thank therapists Kate Harkness, Pamela Stimac, Rebecca Siberman, Lee Wolfson, Jean Picone, Ulrika Feske, Mike Greenwald, and Lin Ehrenpreis for assistance with traumatic grief treatment and Mary McShea, Barbara Kumer, Gloria Klima, Tracey Wang, and Linda Buckley for technical assistance.

1. Lindemann E: Beyond Grief: Studies in Crisis Intervention. New York, Jason Aronson, 1979Google Scholar

2. Rando TA: Treatment of Complicated Mourning. Champaign, Ill, Research Press, 1993Google Scholar

3. Raphael B: The Anatomy of Bereavement. New York, Basic Books, 1983Google Scholar

4. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF III, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, Frank E, Doman J, Miller M: Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 1995; 59:65-79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, Reynolds CR III, Maciejewski PK, Davidson JR, Rosenheck R, Pilkonis PA, Wortman CB, Williams JB, Widiger TA, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Zisook S: Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: a preliminary empirical test. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:67-73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF III, Shear MK, Day N, Beery LC, Newsom JT, Jacobs S: Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:616-623Link, Google Scholar

7. Mawson D, Marks IM, Ramm L, Stern RS: Guided mourning for morbid grief: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:185-193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sireling L, Cohen D, Marks I: Guided mourning for morbid grief: a controlled replication. Behavior Therapy 1988; 19:121-132Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Reynolds CF III, Miller MD, Pasternak RE, Frank E, Perel JM, Cornes C, Huock PR, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, Kupfer DJ: Treatment of bereavement-related major depressive episodes in later life: a controlled study of acute and continuation treatment with nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:202-208Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

11. Foa E, Rothbaum B: Treating the Trauma of Rape: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar