Screening for Complicated Grief Among Project Liberty Service Recipients 18 Months After September 11, 2001

The events of September 11, 2001, raised awareness of disaster-related mental health problems. Disasters commonly leave bereaved people behind, yet the literature related to mental health in the event of disaster pays surprisingly little attention to grief. In particular, it is important to identify and treat complicated grief, a recently identified reaction syndrome related to the loss of a relative or close friend ( 1 , 2 ). This condition, consisting of core symptoms of separation and traumatic distress, possesses unique features that differentiate it from other mental health problems, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression ( 3 , 4 ). We conducted a brief, fully structured telephone survey of recipients of Project Liberty services. Five screening questions for complicated grief were included. The survey was conducted 16-19 months after September 11 as a component of the Project Liberty evaluation. The purpose of this article is todescribe a screening instrument for complicated grief and to report rates and correlates of positive screens from this new instrument.

Methods

Overview of Project Liberty and the telephone interview study

On September 11, 2001, the five boroughs of New York City were declared a federal disaster area after attacks on the World Trade Center, and the disaster declaration was extended to the ten surrounding counties on September 28, 2001. This declaration established eligibility for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) programs ( 5 ), including the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program. That program funds public education, community outreach, and crisis counseling under immediate and regular services programs. The crisis response program established by the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYOMH) was called Project Liberty.

By the end of October 2001 more than 100 mental health agencies, funded by Project Liberty, were providing public education and free crisis counseling for affected individuals. Project Liberty offered counseling services wherever the service recipients wished to have them: in their home, at a community agency, at a school, at a business, or elsewhere in the community. Project Liberty subsidized the demand for counseling services related to the disaster by requiring no payment from users. In addition, this was the first crisis counseling program to include funding for program evaluation.

Given its scope, innovations, and the possible need for response to future disasters, NYOMH was highly committed to evaluating Project Liberty services. The state contracted with the Division of Health Services Research of the Department of Psychiatry at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine to aid in its efforts to evaluate the effectiveness and impact of Project Liberty. We worked collaboratively to develop a brief telephone interview for recipients of crisis counseling services. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish with individuals served at eight Project Liberty sites from January to April 2003. A more complete description of the evaluation project is available elsewhere ( 6 ). Five screening questions for complicated grief were used in this survey, and the results form the basis for this report. Although several validated assessment instruments are available for evaluation of complicated grief ( 1 , 7 , 8 ), all were too lengthy to include in this survey.

Study participants

Our protocol, approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, stipulated that each Project Liberty counselor invite service recipients to provide feedback on services in a telephone interview. Counselors offered a permission-to-contact form to individuals who spoke either English or Spanish and were at least 18 years of age. Service recipients completed the form by indicating their agreement to be contacted and contact information. Forms could be mailed to NYOMH or submitted to the Project Liberty site, or recipients could call a toll-free number to schedule a telephone interview. Respondents received $20 for completing the telephone interview.

Of 214 individuals who agreed to be contacted, 61 did not participate in a telephone interview. Twenty-three were deemed ineligible because they had not received individual crisis counseling, 23 could not be reached, seven were missing a phone number or signature on their forms, six declined to be interviewed, and two were incapable of completing the interview. Four participants were excluded from analyses in this article because they did not indicate whether they knew someone who was killed on September 11. We therefore report data for 149 persons. Of these, 103 (69 percent) were female, 84 (58 percent) were Caucasian, 26 (18 percent) were African American, 29 (20 percent) were Hispanic, and 123 (83 percent) stated that English was their preferred language. Respondents ranged in age from 20 to 86 years (mean±SD=45.8±14.7 years, median=45 years).

Telephone interview procedure

The confidential telephone interview was conducted by trained interviewers who were supervised throughout the data collection period. Average interview time was 46±15 minutes (range=21-106 minutes). Interview questions included reasons for participating in Project Liberty, type and degree of distress and impairment, experience and satisfaction with Project Liberty services, and demographic information. Pertinent to this report, respondents indicated whether they knew anyone who was killed in the attacks. If so, they were asked five questions—about trouble accepting the death, interference of grief in their life, troubling images or thoughts of the death, avoidance of things related to the person who died, and feeling cut off or distant from other people—to screen for complicated grief. Consistent with the rest of the interview, answers were rated as 0, not at all; 1, somewhat; or 2, a lot.

Given the need to limit grief questions to a maximum of five, along with the lack of a universally accepted criteria set for complicated grief, we chose items from the two proposed criteria sets that we judged appropriate for a screening instrument. Both criteria sets included intrusive images of the deceased and avoidance of reminders of the loss. Prigerson and colleagues ( 8 ) included trouble accepting the death and feeling numb and detached. We included a global question about overall interference with ongoing life.

Current major depressive disorder and current PTSD were assessed with a method described by Galea and colleagues ( 9 ) and included criteria for nonclinically trained interviewers to categorize recipient responses as being suggestive of full and subthreshold DSM-IV-TR conditions ( 10 ). We note that PTSD was assessed separately from complicated grief. The questions about exposure to a traumatic event referred to "the World Trade Center attacks" rather than to any specific subevent. In addition, respondents were asked to rate their functioning in the past month with a 4-point scale ranging from poor to excellent separately for each of five domains: job or school, relationships with family and friends, daily household activities, physical health, and community activities.

Statistical analyses

We examined the frequency distribution of screen scores for complicated grief (range of 0 to 10). In order to compare results from the complicated grief screen with those for PTSD and major depressive disorder, we created categories of probable complicated grief and probable subthreshold complicated grief. We chose cutoff scores by examining the frequency distribution and estimating the clinical importance of different symptom levels. Thus we categorized respondents according to the total five-item score, as follows: 8 or higher, complicated grief was likely; between 5 and 7, complicated grief was likely at a subthreshold level; and less than 5, complicated grief was unlikely. We then conducted logistic regression to identify factors related to a positive complicated grief screen by using a dichotomized rating of 5 or greater, indicating a positive screen, or less than 5, indicating a negative screen. Variables included in the analyses were age, gender, race (categorized as non-Hispanic, Caucasian, and English-speaking versus all others), prior history of depression, and relationship to the deceased as an acquaintance, friend, or family member. Variables were entered stepwise and included demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race), history of depression, and relationship to the deceased.

To estimate the impact of symptoms on functioning, we conducted a logistic regression that included a complicated grief screen total of 5 or higher, full or subthreshold PTSD, and probable full or subthreshold depression. We ran higher-order models to examine interactions among depression, PTSD, and complicated grief. Only higher-order models that were statistically significant compared with the previous models were accepted; hence, in all cases, the most parsimonious model was adopted.

Results

Bereavement among Project Liberty clients

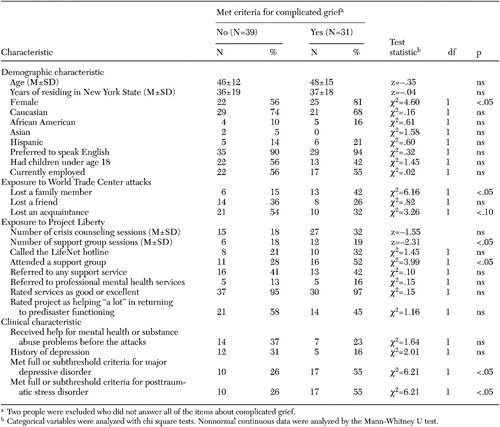

Nearly half of the 149 service recipients we interviewed, or 72 (48 percent), indicated that they knew someone who was killed as a result of the September 11 attacks. Table 1 lists data for comparison of people who knew someone who died and those who did not. In addition to some demographic differences, the group who knew someone who had died used more services and was more likely to endorse items suggestive of full or subthreshold major depressive disorder or PTSD than those without a loss.

|

Nineteen (26 percent) of 72 respondents who knew someone who died on September 11 lost a family member (including child, spouse, sibling, or other relative), 28 (39 percent) lost a friend, and 50 (69 percent) knew an acquaintance who died; 22 (31 percent) knew more than one person who died; hence, the sum of losses by category is greater that 72. For respondents who knew more than one person who died, questions to screen for complicated grief were asked in relation to the most difficult loss. Nineteen (26 percent) identified the loss that affected them the most as the death of a family member, 22 (31 percent) the death of a friend, and 31 (43 percent) the death of an acquaintance. Data from two bereaved respondents who did not respond to items that screened for complicated grief were not included in the analyses.

Characteristics of the five-item screen for complicated grief

Cronbach's alpha for the five items to assess complicated grief indicated good internal consistency (.82). Figure 1 illustrates the endorsement of each screening question by people who knew someone who died in the attacks.

We sought to identify those likely to be experiencing complicated grief by examining the distribution of the total five-item scores ( Figure 2 ). With possible scores of 0 to 10, the higher scores indicating greater complicated grief, we found that the full range of scores was represented. The modal total five-item score was 2 (20 percent; mean±SD=4.3±3.1, median=3.5).

a Sum of five traumatice grief items, each item scored between 0 and 2. Possible total scores ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more severe complicated grief.

The distribution of scores suggests that the 16 respondents with a total score of 8 or higher (23 percent) indicated at least four of five symptoms at the highest level and were considered likely to have the syndrome of complicated grief as described in the literature ( 4 , 11 ). This percentage is similar to that reported for complicated grief among elderly bereaved spouses ( 7 , 12 ). A middle group of 15 respondents (21 percent) had a total score between 5 and 7, a level we considered likely to indicate subthreshold complicated grief. Bereaved respondents were thus divided into those considered to have screened positive for complicated grief, defined by a total score higher than 5, or to have screened negative for complicated grief, with a score less than 5.

Characteristics associated with complicated grief

Logistic regressions indicated that respondents who lost a family member were four times more likely to screen positive for complicated grief than those who lost an acquaintance (odds ratio [OR]=4.24, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.10-16.32, Wald statistic=4.42, p<.05). They were also three times more likely to screen positive than those who lost a friend (OR=3.39, CI=.78-14.77), but this difference was not significant ( Table 2 ). Women were almost three times more likely than men to screen positive (OR=2.79, CI=.82-9.52), but this difference was not significant. Age, race, and history of depression did not significantly predict symptoms of complicated grief.

|

Figure 3 illustrates the rates of probable major depression, PTSD, complicated grief, and their co-occurrence. Among 70 respondents who knew someone who died, 64 percent met our criteria for at least one of these conditions. Among the 45 individuals who met criteria for at least one condition, 29 percent had symptoms of all three conditions and 31 percent had symptoms for two of the three. The remaining 40 percent met criteria for only one condition. Among the 18 individuals who met our criteria for only one condition, 56 percent showed symptoms of only complicated grief, 22 percent indicated only major depression, and 22 percent indicated only PTSD.

a PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder

Given the significant overlap between diagnostic categories, we conducted analyses to determine which syndrome best predicted functioning at the time of the interview. When probable PTSD, major depression, and complicated grief were entered simultaneously into the model, only complicated grief (Wald=9.5, p<.005) and PTSD (Wald=5.2, p<.05) significantly and independently predicted functioning. None of the higher-order models were statistically significant compared with the most basic model.

Discussion

This study has several noteworthy limitations. The sample was selected by enlisting the cooperation of counselors from a selected set of eight Project Liberty service providers during a limited period more than a year after services were initiated. The interview was conducted in Spanish as needed, but it was not offered in Chinese. A large Chinese population in lower Manhattan received Project Liberty services but was not included in the telephone interviews. Complicated grief was identified with five screening questions that had not been tested for reliability and validity. It was not possible to test the predictive power of the screening instrument in this sample. No follow-up clinical interview was conducted to establish the diagnosis of complicated grief or other DSM-IV conditions. In particular, the cutoff score we used for a positive screen has not been validated. However, we believe its appropriateness is supported by the fact that this score differentiated people who were likely to be closer to the person lost, and the cutoff score used was able to predict impairment. For these reasons our results should be viewed as provisional. It will be important to test the usefulness of this screening instrument in identifying individuals who are "diagnosed" as having complicated grief with other validated instruments.

However, given these limitations, our survey of Project Liberty recipients is the first to include screening questions for complicated grief in a postdisaster evaluation. Much attention has rightly been paid to disaster-related PTSD ( 13 ) and depression. However, problem grief reactions are often neglected in postdisaster surveys. We found that 44 percent of service recipients who knew someone who died in the September 11 attacks screened positive for complicated grief more than a year after the event.

Pfefferbaum and colleagues ( 14 ) examined grief in a survey of 86 individuals seeking help from the federally funded Project Heartland mental health program established by the Oklahoma Department of Health and Substance Abuse Services after the Oklahoma City bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah building. Results are similar to our findings. Forty respondents (47 percent) reported they knew someone who was killed in the bombing. Complicated grief was inferred from findings that grief and PTSD reactions interacted to account for ratings of functional impairment. Among those with high PTSD symptom scores, higher grief led to higher levels of functional impairment, and neither grief nor PTSD reactions alone contributed to impairment. The authors suggested that their findings supported the construct of traumatic (complicated) grief.

Accumulating evidence indicates that complicated grief is a chronic debilitating syndrome that predicts negative health outcomes. Symptoms reflect separation distress and trauma-like symptoms indicative of devastation from bereavement ( 15 ). Studies have shown that this condition tends to be chronic and persistent and to be associated with significant functional impairment, negative health behaviors, physical illness, and risk of suicide ( 12 , 16 , 17 ). Grief resembles depression, but complicated grief does not respond well to proven efficacious treatments for depression ( 18 , 19 , 20 ). A recent randomized controlled study showed that a targeted treatment produced a better outcome than a well-validated treatment for depression ( 21 ). Complicated grief differs from PTSD in the prominence of separation distress and the experience of trauma in response to loss rather than to a violent event. Nearly one-third of the Project Liberty service recipients we interviewed who screened positive for complicated grief did not meet even subthreshold criteria for probable major depression or PTSD, further supporting the distinction of grief reactions from both of these existing DSM-IV conditions. Complicated grief was the strongest contributor to impairment.

Risk factors for complicated grief include a very close relationship to the person who died, an anxious ( 22 ) or fearful-avoidant ( 23 ) attachment style, and a positive caregiving experience ( 24 ). Although we did not obtain information related to the quality of the relationship, people who lost a family member were significantly more likely to screen positive for complicated grief.

Our results have implications for disaster response planning. Approximately 2,800 people were killed in New York City on September 11, 2001. NYOMH and FEMA estimated that locally, approximately 3.1 million people were at risk of experiencing emotional distress as a result of the disaster ( 25 ). A rapid needs assessment focused only on PTSD because a public-academic collaboration concluded that this was the only trauma-related disorder for which the research base was sufficiently strong. Our findings suggest that this planning strategy overlooked a large group of bereaved individuals with complicated grief without PTSD.

By March 2002 a conservative estimate indicated that Project Liberty had reached 91,000 people through 42,000 service encounters ( 5 ), including 4,154 people who lost a family member. Nearly half (47 percent) of the people we interviewed reported that they knew someone personally who had died in the attacks, suggesting that this group represented a large proportion of those continuing to accept services more than a year after the attacks. In addition, those who knew someone who died attended significantly more individual counseling and support group sessions than those who did not. Project Liberty was aimed at ameliorating psychological distress and returning individuals to their previous levels of functioning ( 5 ). Our results underscore the need to address complicated grief in order to achieve this objective.

Conclusions

In summary, this is the first survey that we know of to screen for disaster-related complicated grief. We found that a substantial subgroup (44 percent) of individuals who knew someone who died in the World Trade Center attacks and who sought Project Liberty services more than a year after the disaster screened positive for complicated grief (23 percent) or subthreshold symptoms (21 percent). These rates should not be thought to reflect community rates of complicated grief because the study pertained to individuals who sought counseling and was not a random sample of the community. Furthermore, all survey respondents received services and so may have received treatment for their symptoms of complicated grief. Still, individuals who screened positive for complicated grief in our survey had increased risk of other common disaster-related mental health disorders, as well as significantly greater functional impairment than those who screened negative for complicated grief. Clinicians and researchers working with victims of disaster need to recognize and treat complicated grief.

Acknowledgments

This evaluation was funded by grant FEMA-1391-DR-NY (titled "Project Liberty: Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program") to New York State from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administered the grant. This study was also funded by grants MH-60783, MH-30915, and MH-52247 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the University of Pittsburgh. The authors express their appreciation to Wendy R. Ulaszek, Ph.D., and Nancy H. Covell, Ph.D.

1. Horowitz MJ, Siegel B, Holen A, et al: Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:904-910, 1997Google Scholar

2. Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, et al: Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: a rationale and preliminary empirical test. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:67-73, 1999Google Scholar

3. Jacobs SC: Pathologic Grief: Maladaptation to Loss. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

4. Lichtenthal WG, Cruess DG, Prigerson HG: A case for establishing complicated grief as a distinct mental disorder in DSM-V. Clinical Psychology Review 24:637-662, 2004Google Scholar

5. Felton CJ: Project Liberty: a public health response to New Yorkers' mental health needs arising from the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79:429-433, 2002Google Scholar

6. Ulaszek WR, Dunakin LK, Donahue SA, et al: Using staff focus groups to refine a service recipient feedback process: an example from Project Liberty, New York's 9/11 mental health response program. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 28:209-216, 2005Google Scholar

7. Burnett P, Middleton W, Raphael B, et al: Measuring core bereavement phenomena. Psychological Medicine 27:49-57, 1997Google Scholar

8. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, et al: Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research 59:65-79, 1995Google Scholar

9. Galea S, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982-987, 2002Google Scholar

10. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

11. Shear MK, Frank E, Foa EB, et al: Traumatic grief treatment: a pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1506-1508, 2001Google Scholar

12. Ott CH: The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Studies 27:249-272, 2003Google Scholar

13. Herman D, Susser E, Felton C: Rates and Treatment Costs of Mental Disorders Stemming From the World Trade Center Terrorist Attacks: An Initial Needs Assessment. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2002Google Scholar

14. Pfefferbaum B, Call JA, Lewegraf SJ, et al: Traumatic grief in a convenience sample of victims seeking support services after a terrorist incident. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 13:19-24, 2001Google Scholar

15. Jacobs S: Traumatic Grief: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. Philadelphia, Brunner/Mazel, 1999Google Scholar

16. Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, et al: Complicated grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1484-1486, 1996Google Scholar

17. Szanto K, Prigerson HG, Houck PR, et al: Suicidal ideation in elderly bereaved: the role of complicated grief. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 27:194-207, 1997Google Scholar

18. Pasternak RE, Reynolds CF, Frank E, et al: The temporal course of depressive symptoms and grief intensity in late-life spousal bereavement. Depression 1, 1993Google Scholar

19. Reynolds CF, Miller MD, Pasternak RE, et al: Treatment of bereavement-related major depressive episodes in later life: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acute and continuation treatment with nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:202-208, 1999Google Scholar

20. Zisook S, Shuchter SR: Treatment of the depressions of bereavement. American Behavioral Scientist 44:782-797, 2001Google Scholar

21. Shear K, Frank E, Houck P, et al: Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:2601-2608, 2005Google Scholar

22. Field NP, Sundin EC: Attachment style in adjustment to conjugal bereavement. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 18:347-361, 2001Google Scholar

23. Fraley RC, Bonanno GA: Attachment and loss: a test of three competing models on the association between attachment-related avoidance and adaptation bereavement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30:878-890, 2004Google Scholar

24. Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A: Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychology and Aging 19:668-675, 2004Google Scholar

25. Project Liberty Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program, Regular Services Program Application. FEMA-1391-DR-NY. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2001Google Scholar