Gender-Related Differences in the Characteristics of Problem Gamblers Using a Gambling Helpline

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The characteristics of male and female gamblers utilizing a gambling helpline were examined to identify gender-related differences. METHOD: The authors performed logistic regression analyses on data obtained in 1998–1999 from callers to a gambling helpline serving southern New England. RESULTS: Of the 562 phone calls used in the analyses, 349 (62.1%) were from male callers and 213 (37.9%) from female callers. Gender-related differences were observed in reported patterns of gambling, gambling-related problems, borrowing and indebtedness, legal problems, suicidality, and treatment for mental health and gambling problems. Male gamblers were more likely than female gamblers to report problems with strategic or “face-to-face” forms of gambling, e.g., blackjack or poker. Female gamblers were more likely to report problems with nonstrategic, less interpersonally interactive forms of gambling, e.g., slot machines or bingo. Female gamblers were more likely to report receiving nongambling-related mental health treatment. Male gamblers were more likely to report a drug problem or an arrest related to gambling. High rates of debt and psychiatric symptoms related to gambling, including anxiety and depression, were observed in both groups. CONCLUSIONS: Individuals with gambling disorders have gender-related differences in underlying motivations to gamble and in problems generated by excessive gambling. Different strategies may be necessary to maximize treatment efficacy for men and for women with gambling problems.

Historically, pathological gambling has been viewed as a male-dominated illness, with a ratio of approximately 2:1 in its prevalence in men and women in the general adult population (1). Many investigations of the etiology and treatment of pathological gambling have involved predominantly or exclusively male subjects (2), generating a deficiency in our knowledge about women with gambling problems. Studies involving both men and women with pathological gambling have demonstrated gender-related behavioral and biological differences (3, 4). For example, differential distribution in male and female subjects of allelic variants of candidate genes for pathological gambling has been reported (4). Gender-related differences have also been observed in utilization of treatment modalities; e.g., historically, 93%–98% of Gamblers Anonymous participants have been male (5). Despite these differences, relatively few structured investigations have explored gender-related characteristics of specific groups of individuals with gambling problems (2).

Self-destructive gambling behavior in individuals with pathological gambling is often undetected or unaddressed for significant periods of time. A current health care challenge is to identify people with pathological gambling and engage them in treatment during earlier stages of the illness. Gambling helplines constitute one method for assisting problem gamblers (6–9). Helplines have been used to address questions about or facilitate treatment of various problems, e.g., cocaine abuse (10). In the United States, there are toll-free telephone services providing assistance to individuals seeking help for gambling problems (7, 9), and similar networks operate in other countries, including the United Kingdom and New Zealand (6, 8). Despite the widespread use of gambling helplines, relatively few studies have explored the characteristics of problem gamblers that use these services (7, 9).

The goal of the present study was to determine whether there were gender-related differences in the characteristics of individuals with gambling problems. Given our observations of individuals with gambling problems in prevention and treatment settings, we hypothesized that male and female problem gamblers differ with regard to patterns and consequences of problematic gambling. Specifically, we had observed an increase in the number of women with gambling problems in treatment settings after the introduction of casinos in Connecticut, with many women reporting problems with slot machine gambling. In an initial effort to explore gender-related differences in problem gamblers, we examined the information provided by gamblers who used a gambling helpline.

Method

Data were gathered from callers to the helpline of the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling. The characteristics of the helpline have been described elsewhere (9). Briefly, the helpline is operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, a private nonprofit organization and affiliate of the National Council on Problem Gambling. Calls to the helpline are addressed by staff members of the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, who have training and experience in the areas of problem and pathological gambling.

Data for the present analysis were obtained from the 1,260 calls received from February 15, 1998, to February 14, 1999, inclusive. Of these, 1,024 calls were from or regarding individuals with gambling problems. We chose to focus the present analysis on calls from the gamblers themselves (613 of the 1,024 calls). Of these 613 phone calls, 51 were excluded because the caller was unwilling to provide information, leaving 562 calls for the present analysis.

Questionnaire items were grouped essentially as described previously (9) into eight categories: 1) demographic characteristics (age, annual income, Caucasian race, African American race, Hispanic ethnicity, education level, and marital status), 2) gambling types and durations (years of gambling, years of problematic gambling, number of problematic gambling types), 3) psychiatric symptoms secondary to gambling (anxiety, depression, suicidality, suicide attempt[s]), 4) problems secondary to gambling (family problems, financial problems, illegal activity without arrest, arrest), 5) financial problems (indebtedness, bankruptcy), 6) types of debt (debt to institutions such as a bank or the government, debt to a bookie or loan shark, debt to casino credit line or credit card, debt to acquaintances, including friends, family members, co-workers), 7) drug and alcohol problems, and 8) treatment (mental health treatment not related to gambling, professional treatment for gambling, self-help for gambling). The mental health variable in the treatment category refers specifically to nondrug, nongambling mental health care to address depression, anxiety, or other mental health problems. The variable “number of problematic gambling types” was derived from the total number of acknowledged noncasino and casino forms of gambling problems, as reported previously (9). Gambling forms were defined as strategic (e.g., cards or sports gambling) or nonstrategic (e.g., lottery or slot machine gambling), as described previously (9).

Logistic regression analyses were completed for each of the eight categories of variables to determine relationships to the dependent variable gender (male versus female gender). If the overall model for a category was significant, individual variables within the model were examined for significant relationship to male gender by using the results of the logistic regression analysis. Before completion of the logistic regression analyses, independent variables in each category were examined for colinearity and multicolinearity by using correlation matrices and the equivalent model that was adjusted by weight matrix. The SAS System (Cary, N.C.) was used for coding data, estimating models, and performing computations. Items answered as “don’t know” were excluded from data analyses.

Results

The callers with gambling problems who provided data for the study included 349 men (62.1%) and 213 women (37.9%). Multivariate analyses revealed that each of the eight questionnaire categories distinguished the groups of male and female gamblers.

Demographic Characteristics

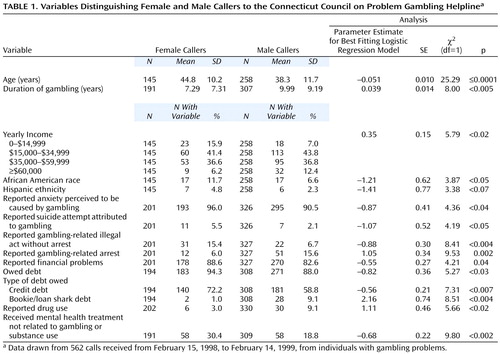

Male and female gamblers had significantly different demographic characteristics (χ2=46.27, df=7, p<0.0001). Of the specific demographic characteristics examined, age, yearly income, and African American race significantly distinguished male and female gamblers (Table 1). Compared with the female gamblers, the male gamblers were younger, more likely to have a reported annual income of more than $60,000, and less likely to be of African American origin. The gender difference in the proportion of gamblers with Hispanic ethnicity approached but did not reach statistical significance.

Duration of Gambling and Problem Gambling

Male and female gamblers were significantly different in duration of gambling (χ2=15.18, df=3, p<0.002). Male gamblers were more likely than female gamblers to report a longer duration of gambling, although neither the reported duration of problematic gambling nor the number of types of problematic gambling significantly distinguished the groups.

Types of Gambling Problems

Secondary analyses were performed to investigate the relationship of gender to types of problematic gambling. Gambling problems, categorized by style (strategic, nonstrategic, or both strategic and nonstrategic), were found to differ significantly as a function of gender (χ2=116.81, df=2, p≤0.001). Male gamblers were more likely to report problems with only strategic forms of gambling (male gamblers: N=132 of 324, 40.7%; female gamblers: N=16 of 200, 8.0%) or both strategic and nonstrategic gambling (male gamblers: N=122 of 324, 37.7%; female gamblers: N=51 of 200, 25.5%) and less likely to report problems with only nonstrategic gambling (male gamblers: N=70 of 324, 21.6%; female gamblers: N=133 of 200, 66.5%). Significant gender-related differences were observed for the location of problematic gambling (casino, noncasino, or both casino and noncasino) (χ2=9.58, df=2, p=0.008). The majority of the difference was accounted for by the male gamblers more frequently reporting problems with only noncasino gambling (male gamblers: N=56 of 327, 17.1%; female gamblers: N=18 of 201, 9.0%) and the female gamblers more frequently reporting problems with only casino gambling (male gamblers: N=145 of 327, 44.3%; female gamblers: N=112 of 201, 55.7%).

Chi-square analyses were performed to investigate the relationship between gender and problems with each of the 12 most frequently acknowledged types of casino and noncasino gambling. Significant gender-related differences were observed for each of the six most frequently acknowledged forms of casino gambling, with male gamblers more likely than female gamblers to report problems with blackjack (N=152 of 329, 46.2%, versus N=41 of 203, 20.2%) (χ2=36.72, df=1, p≤0.001), roulette (N=44 of 329, 13.4%, versus N=9 of 203, 4.4%) (χ2=11.19, df=1, p≤0.001), poker (N=39 of 329, 11.9%, versus N=9 of 203, 4.4%) (χ2=8.42, df=1, p≤0.004), or craps/dice (N=45 of 329, 13.7%, versus N=4 of 203, 2.0%) (χ2=20.58, df=1, p≤0.001) and less likely than female gamblers to report problems with slot machines (N=122 of 329, 37.1%, versus N=157 of 203, 77.3%) (χ2=81.58, df=1, p≤0.000) or bingo (N=2 of 329, 0.6%, versus N=21 of 203, 10.3%) (χ2=28.72, df=1, p≤0.001). Significant gender-related differences were also observed for three of the six most frequently acknowledged forms of noncasino gambling, with male gamblers more likely than female gamblers to report problems with gambling on sports (N=53 of 329, 16.1%, versus N=3 of 203, 1.5%) (χ2=28.54, df=1, p≤0.001), dog racing (N=32 of 329, 9.7%, versus N=6 of 203, 3.0%) (χ2=8.68, df=1, p=0.003), or horse racing (N=31 of 329, 9.4%, versus N=2 of 203, 1.0%) (χ2=15.36, df=1, p≤0.001). No statistically significant gender differences were observed in reported frequencies of problems with lottery, jai alai, or card gambling.

Psychiatric Symptoms Related to Gambling

Male and female gamblers had significantly different psychiatric symptoms that they perceived to be caused by gambling (χ2=12.26, df=4, p<0.02). Although high rates of anxiety (Table 1) and depression (male gamblers: N=254 of 326, 77.9%; female gamblers: N=169 of 201, 84.1%) perceived to be caused by gambling were observed for both men and women, female gamblers were significantly more likely than male gamblers to report anxiety and suicide attempts attributed to gambling (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were observed between men and women in reports of depression or suicidality perceived to be caused by gambling.

Problems Perceived as Caused by Gambling

Male and female gamblers reported significantly different problems perceived to be caused by gambling (χ2=25.68, df=4, p<0.0001). Of the specific types of problems reported, legal problems and financial problems distinguished male and female gamblers (Table 1). Male gamblers were significantly more likely than female gamblers to report gambling-related arrests, and female gamblers were significantly more likely to report gambling-related illegal activities in the absence of arrest. Female gamblers were more likely to report financial problems caused by gambling, although high rates of these problems were observed in both groups.

Financial Problems

Male and female gamblers had significantly different financial problems related to gambling (χ2=6.11, df=2, p<0.05). Female gamblers were significantly more likely than male gamblers to report having debts, but high rates of indebtedness were observed in both groups (Table 1).

Types of Debt

Male and female gamblers were distinguished by the types of debt they owed (χ2=25.61, df=4, p<0.0001). Male gamblers were significantly more likely than female gamblers to report indebtedness to a bookie or loan shark, and female gamblers were significantly more likely to report credit debt (Table 1).

Excessive Drug or Alcohol Use

Male and female gamblers reported significantly different patterns of drug and alcohol problems (χ2=9.11, df=2, p=0.01). Male gamblers were significantly more likely than female gamblers to report drug problems (Table 1). No statistically significant difference between the groups was observed in the rates of reported alcohol problems, with 14.9% of the female gamblers (N=30 of 202) and 20.0% of the male gamblers (N=66 of 330) acknowledging problems with alcohol.

Treatments Received

The types of treatment received by male and female gamblers were significantly different (χ2=13.74, df=3, p<0.004). Reported rates of nongambling, non-substance-related mental health treatment were significantly higher for female gamblers than for male gamblers (Table 1). Overall low and not significantly different rates between groups were observed for prior professional gambling treatment (male gamblers: N=10 of 309, 3.2%; female gamblers: N=3 of 191, 1.6%) and 12-step gambling program participation (male gamblers: N=42 of 309, 13.6%; female gamblers: N=16 of 191, 8.4%).

Discussion

The present study is the first to our knowledge to investigate specifically gender-related differences in gamblers using a gambling helpline. As noted previously (9), high rates of psychiatric symptoms, notably anxiety (92.6%) and depression (80.2%), were attributed to gambling. These rates approximate those attributed to cocaine use by cocaine users who utilized a cocaine helpline (anxiety, 85%; depression, 83%) (10). The high rates of gambling-induced anxiety and depression might reflect a vulnerability of problem gamblers to experience uncomfortable or distressing somatic states. In findings that are consistent with this idea, pathological gamblers scored higher than nonpsychiatric community comparison subjects on all scales of the SCL-90, including those for depression and anxiety (11). Similarly, substance abusers with gambling problems scored higher than those without gambling problems on multiple SCL-90 measures, including those for depression and anxiety (12). Higher than expected rates of mental and physical health problems have also been associated with gambling problems (13). Taken together, the observed high rates of gambling-related anxiety and depression are consistent with those reported in prior studies of problem gamblers, and the frequencies of gambling-related symptoms are similar to the frequencies of cocaine-related symptoms reported by cocaine abusers using a similar service.

Relatively high rates of suicidality caused by gambling (26.7%) were observed in this study. These rates were lower than the rate of close to 90% among callers meeting the criteria for pathological gambling who used a helpline in New Zealand (6). In the New Zealand study, all callers were reported to meet the criteria for pathological gambling. This finding, in conjunction with the higher rate of suicidality, suggests the New Zealand group might have been experiencing more severe gambling problems than the callers in the present study. Rates of attempted suicide caused by gambling in the present study (3.4%) were lower than those reported previously for individuals with pathological gambling (17%–24%) (14). Differences in rates of suicidality and suicide attempts between the present and previous studies likely reflect differences in severity of gambling pathology and type of suicidality measured (i.e., suicidality caused by gambling compared with any suicidality). The rate of prior mental health treatment reported by callers (23.2%) was markedly lower than the acknowledged rates of psychiatric symptoms, suggesting a need for additional efforts to engage problem gamblers into mental health treatment.

Helpline callers described gambling problems of prolonged duration (average >2 years) with high rates of distress and associated problems. Despite the significant extent and duration of gambling problems, few callers had received professional gambling treatment or participated in Gamblers Anonymous. These findings reinforce the need to engage problem gamblers in gambling treatment, ideally in conjunction with other mental health treatment.

High rates of substance use disorders have been reported in individuals with pathological gambling (15, 16). The lower rates observed in the current study could reflect the specific questions asked (questions about self-defined excessive or problematic drug or alcohol use) or differences in the subjects’ characteristics (e.g., the possibility of less severe gambling disorders). However, the ratio of women to men who reported alcohol problems (approximately 3:4) in the present study was higher than in the general population (approximately 1:4) (17) and similar to that reported for individuals with pathological gambling who are in treatment (18).

Disproportionately few calls were received from minorities, particularly Hispanic and African American men, compared with estimated rates of problem gambling in these groups. The proportion of Hispanic callers was different from census estimates of the proportion of Hispanic persons in the population of Connecticut (3.2% of helpline callers, compared with 8.2% of the Connecticut population), whereas the census estimates more closely approximated the percentage of calls from African Americans (8.4% of helpline callers, compared with 9.3% of the Connecticut population) (19). Higher rates of problem gambling have consistently been reported in African Americans, with two- to three-fold higher rates than in Caucasians (16, 20). Findings in Hispanic groups have been mixed, with some reports of higher (7) and others of modestly lower rates in Hispanic groups, compared with Caucasians (20). Other helplines (e.g., those for suicide prevention) are most frequently used by Caucasian female callers (21). The underrepresentation of minority male callers to the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling helpline could in part reflect gender-related differences in help-seeking (3). Together, these findings suggest a need to make gambling helpline services more available or attractive to minority groups, particularly minority men, e.g., through the use of additional advertising or bilingual or culturally sensitive helpline personnel.

Female problem gamblers, compared with male problem gamblers, reported shorter durations of gambling despite similar durations of problematic gambling before contacting the gambling helpline. This finding raises the possibility that women, once they begin gambling, develop gambling problems at a more rapid rate than men. Such a pattern, termed telescoping, has been observed in women with alcohol dependence, suggesting that women are more likely than men to move rapidly through the multiple landmark events associated with the development and progression of alcoholism (22). The difference we observed could also be related to types of gambling, e.g., casino slot machine gambling, that are more frequently problematic for women. It has been suggested that machine gambling leads more rapidly to problematic use, given its greater rapidity of action (23).

Gender differences in patterns of problem gambling could reflect differences in motivations to gamble. Male gamblers in the present study were significantly younger and more likely to report problems with strategic forms of gambling. In contrast to female gamblers, who may more likely report gambling as a means of escape from distressing problems (3, 24), male gamblers may more often seek ego enhancement through the thrill of competitive risk-taking that targets large wins. This idea is consistent with the observation that male callers were more likely to report problems with strategic forms of gambling and female callers with nonstrategic forms. Consistent with the possibility of male thrill-seeking, studies have found higher levels of sensation seeking or impulsivity in predominantly male groups with pathological gambling (25) and among male adolescents who frequently gamble (26). In comparison, lower levels of sensation seeking were found to correlate with increased fruit machine gambling in women (27). However, there also exist reports of normal or low levels of impulsivity and sensation seeking in predominantly male groups of individuals with pathological gambling (28). Although gambling patterns suggest men may engage in more action-oriented (e.g., table or sports gambling) and women in more escape-oriented (e.g., slots) forms of gambling, studies have demonstrated high rates of dissociative experiences in both men and women with pathological gambling (3, 29). Further studies are needed to better define the relationships between gender, thrill-seeking, dissociation, impulsivity, and underlying motivations to gamble in individuals with gambling problems.

Some of the present findings, for example, higher rates of anxiety attributed to gambling in female callers, are consistent with general gender-related characteristics, such as higher rates of anxiety disorders in women (30). The clinical significance of this difference and some others (e.g., presence of debt) are questionable due to the high rates of acknowledgment and the large sample size. Consistent with the current study, women in general are more like likely than men to attempt suicide (30) and seek mental health treatment (3). Other differences appear more specific to problem gamblers; e.g., men were more than eight times as likely as women to owe money to a loan shark or bookie. This finding is consistent with prior reports that women are more likely to opt for legalized gambling (3). Considering the recent expansion in legalized gambling and easy access to legal credit, an increase in the proportion of women with gambling problems would be predicted.

We acknowledge several caveats in interpreting the data obtained from the helpline callers. First, several factors, including callers’ ability to recollect past experiences and willingness to provide information, could influence the responses received. Second, regional differences in gambling opportunities must be considered. Connecticut has two of the world’s largest casinos but no automated lottery terminals. Third, data were collected within a distinct time period. Given changes in gambling opportunities and available treatment services, there will likely be changes over time in the characteristics of callers. Fourth, the present study lacked instruments from which formal diagnoses of pathological gambling or other mental health disorders could be determined.

Gambling helplines serve extensively as a means to direct large groups of people with gambling problems to appropriate treatments and thus have a major clinical impact. The findings of gender-related differences in gambling helpline callers emphasize the importance of consideration of gender in the study and treatment of individuals with gambling problems.

|

Presented in part at the College on Problems in Drug Dependence, Acapulco, Mexico, June 12–17, 1999; the World Congress of Psychiatry, Hamburg, Germany, Aug. 6–11, 1999; the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Acapulco, Mexico, Dec. 12–16, 1999; and the International Conference on Gaming and Risk-Taking, Las Vegas, Nev., June 13–16, 2000. Received Aug. 18, 2000; revisions received Jan. 31 and March 9, 2001; accepted March 30, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine; and the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, Guilford, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Potenza, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, Connecticut Mental Health Center, Room S-104, 34 Park St., New Haven, CT 06519; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, a Drug Abuse Research Scholar Program in Psychiatry Award from APA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-00366), grant AA-00171 from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, and grants from the National Center for Responsible Gaming; the Department of Veterans Affairs VISN 1 Mental Illness Research, Educational, and Clinical Center; the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation; the Mohegan Sun Casino; and the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. The authors thank Dawn Hemstock and Elaine LaVelle for comments on the helpline data form, Marek Chawarski for advice on statistical analyses, and Carolyn Mazure for comments on the manuscript.

1. Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J: Estimating the Prevalence of Disordered Gambling in the United States and Canada: A Meta-Analysis. Boston, Harvard Medical School Division on Addictions, 1997Google Scholar

2. Mark ME, Lesieur HR: A feminist critique of problem gambling research. Br J Addict 1992; 87:549-565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lesieur H, Blume SB: When lady luck loses: women and compulsive gambling, in Feminist Perspectives on Addictions. Edited by van den Bergh N. New York, Springer, 1991, pp 181-197Google Scholar

4. Ibanez A, Perez de Castro I, Fernandez-Piqueras J, Vlanco C, Saiz-Ruiz J: Pathological gambling and DNA polymorphic markers at MAO-A and MAO-B genes. Mol Psychiatry 2000; 5:105-109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lesieur HR: Report on Pathological Gambling. Trenton, NJ, Governor’s Advisory Commission on Gambling, 1988, pp 104-165Google Scholar

6. Sullivan S, Abbott M, McAvoy B, Arroll B: Pathological gamblers—will they use a new telephone hotline? NZ Med J 1994; 107:313-315Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cuadrado M: A comparison of Hispanic and Anglo calls to a gambling hotline. J Gambling Studies 1999; 15:71-82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Griffiths M, Scarfe A, Bellringer P: The UK national telephone gambling helpline: results on the first year of operation. J Gambling Studies 1999; 15:83-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Potenza MN, Steinberg MA, McLaughlin SD, Rounsaville BJ, O’Malley SS: Illegal behaviors in problem gambling: analysis of data from a gambling helpline. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2000; 28:389-403Medline, Google Scholar

10. Washton AM, Gold MS, Pottash AC: The 800-COCAINE helpline: survey of 500 callers. NIDA Res Monogr 1984; 55:224-230Medline, Google Scholar

11. Blaszczynski AP, McConaghy N: SCL-90 assessed psychopathology in pathological gamblers. Psychol Rep 1988; 62:547-552Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Petry N: Psychiatric symptoms in problem gambling and non-problem gambling substance abusers. Am J Addict 2000; 9:163-171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. James K: National Gambling Impact Study Commission: Final Report to Congress 1999. http://www.ngisc.gov/reports/finrpt.htmlGoogle Scholar

14. DeCaria CM, Hollander E, Grossman R, Wong CM, Mosovich SA, Cherkasky S: Diagnosis, neurobiology, and treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 8):80-83; discussion, 83-84Google Scholar

15. Crockford DN, el-Guebaly N: Psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gambling: a critical review. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43:43-50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM III, Spitznagel EL: Taking chances: problem gamblers and mental health disorders: results from the St Louis Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Am J Public Health 1998; 88:1093-1096Google Scholar

17. Grant BJ: The relationship between ethanol intake and DSM-III-R alcohol dependence: results of a national survey. J Subst Abuse 1993; 5:257-267Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Toneatto T: Relationship between gender and substance use among treatment-seeking gamblers. eGambling 2000. http://www.camh.net/egambling/issue1/research/Google Scholar

19. United States Census Internet Site: Population estimates for States by race and Hispanic origin, 2000. http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/state/srh/srh98.txtGoogle Scholar

20. National Opinion Research Center: Gambling Impact and Behavior Study. Chicago, National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, 1999. http://www.norc.uchicago.edu/new/gamb-fin.htmGoogle Scholar

21. Shaffer D, Garland A, Gould M, Fisher P, Trautman P: Preventing teenage suicide: a critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:675-687Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Randall C, Robert JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connor GJ, Mattson ME: Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: a gender comparison. J Stud Alcohol 1999; 60:252-260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Musante J: Women and gambling. Connecticut Post, Sept 22, 1999, pp A1, A12Google Scholar

24. Trevorrow K, Moore S: The association between loneliness, social isolation, and women’s electronic gaming machine gambling. J Gambling Studies 1998; 14:263-284Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Blaszczynski A, Steel Z, McConaghy N: Impulsivity in pathological gambling: the antisocial impulsivist. Addiction 1997; 92:75-87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Vitaro F, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE: Dispositional predictors of problem gambling in male adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1769-1770Google Scholar

27. Coventry KR, Constable B: Physiological arousal and sensation-seeking in female fruit machine gamblers. Addiction 1999; 94:425-430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Allcock CC, Grace DM: Pathological gamblers are neither impulsive nor sensation-seekers. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1988; 22:307-311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kofoed L, Morgan TJ, Buchkoski J, Carr R: Dissociative experiences scale and MMPI-2 scores in video poker gamblers, other gamblers, and alcoholic controls. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:58-60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kaplan H, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA: Synopsis of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1994Google Scholar