Comorbidity and Course of Psychiatric Disorders in a Community Sample of Former Prisoners of War

Abstract

Objective:The authors assessed DSM-III-R disorders among American former prisoners of war. Comorbidity, time of onset, and the relationship of trauma severity to complicated versus uncomplicated posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were examined. Method:A community sample (N=262) of men exposed to combat and imprisonment was assessed by clinicians using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.Results:The rates of comorbidity among the men with PTSD were lower than rates from community samples assessed by lay interviewers. Over one-third of the cases of lifetime PTSD were uncomplicated by another axis I disorder; over one-half of the cases of current PTSD were uncomplicated. PTSD almost always emerged soon after exposure to trauma. Lifetime PTSD was associated with increased risk of lifetime panic disorder, major depression, alcohol abuse/dependence, and social phobia. Current PTSD was associated with increased risk of current panic disorder, dysthymia, social phobia, major depression, and generalized anxiety disorder. Relative to PTSD, the onset of the comorbid disorders was as follows: major depression, predominantly secondary; alcohol abuse/dependence and agoraphobia, predominantly concurrent (same year); social phobia, equal proportions primary and concurrent; and panic disorder, equal proportions concurrent and secondary. Trauma exposure was comparable in the subjects with complicated and uncomplicated PTSD.Conclusions:The types of comorbid diagnoses and their patterns of onset were comparable to the diagnoses and patterns observed in other community samples. The findings support the validity of the PTSD construct; PTSD can be distinguished from comorbid disorders. Uncomplicated PTSD may be more common than previous studies suggest, particularly in clinician-assessed subjects exposed to severe trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1740-1745

Studies of comorbidity in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1–9) have reported such high rates that the idea that PTSD can be clearly differentiated from other psychiatric disorders may be challenged (10). Clearly, when compared with trauma-exposed individuals who do not develop PTSD, individuals with PTSD exhibit increased rates of other disorders (6–9). What is not clear, however, is whether PTSD is more frequently complicated by other psychiatric disorders than are other DSM axis I disorders. The majority (79%) of lifetime disorders assessed in the National Comorbidity Survey (11) were comorbid disorders. Comorbid lifetime generalized anxiety occurred with other lifetime axis I disorders in 90% of the cases (12), comorbid lifetime major depression occurred in 74% of the cases (13), and comorbid lifetime PTSD occurred in 88% of men and 79% of women (4). In the National Comorbidity Survey, rates of comorbidity in PTSD appear comparable to rates observed in other axis I disorders.

Surveys of trauma-exposed community samples suggest that PTSD is highly comorbid with other disorders (6–9). Among subjects with PTSD, reported lifetime comorbidity rates have ranged from 61% (7) to 99% (6). Current PTSD was complicated by other current disorders in 50%–95% of the cases (6,8). The lifetime disorders significantly associated with PTSD include major depression, 26%–53% (6–9); substance abuse, 14%–73% (6, 7); generalized anxiety disorder, 25%–39% (8,9); panic disorder, 9%–37% (8, 9); dysthymia, 21% (6); phobia, 22%–33% (6, 8, 9); obsessive-compulsive disorder, 4%–13% (6, 8, 9); agoraphobia, 6% (8); and somatization disorder, 4% (8). The comorbidity rate of 99% in the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (6) included the diagnosis of antisocial personality, found in 31% of the individuals with PTSD. The comorbidity rate of 61% in a study of Israeli combat veterans (7) included personality disorder, found in 24% of those with PTSD.

Community studies of comorbidity in PTSD (1–9) have been based on samples in which the group’s average trauma exposure was moderate to moderately severe. Subjects’ reported trauma exposure was frequently limited to a single episode. Most assessments were not conducted by experienced clinicians, and the majority of the diagnoses were made with the use of some version of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (14). To our knowledge, there is no published evidence to date documenting comorbidity in a community sample with PTSD that is based exclusively on clinician-administered structured interviews.

Comorbidity rates are determined by many factors, including assessment methods (15). Experienced clinicians conducted all assessments in only one study (7). With two exceptions (7, 8), community studies have relied on the DIS or one of its derivatives (e.g., the Composite International Diagnostic Interview [16]). While the DIS is economical in that it may be administered by lay interviewers, convergence of its results with results from clinician-administered structured diagnostic interviews may be low. Agreement between results from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview and those from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (17) was low for generalized anxiety disorder (18) and phobic disorders (19). This lack of convergence may occur for a variety of reasons, including differences between interviews in the wording and sequence of questions, the freedom of clinicians to add probe questions, and clinicians’ possibly higher thresholds for assigning a diagnosis (20). Also, clinicians may use clinical judgment when assigning symptoms to one diagnostic category or another. For example, in a survey of Vietnam combat veterans (21), the DIS administered by lay interviewers suggested that 35% of the subjects with PTSD met the criteria for schizophrenia. Using clinical interviews, the attending clinicians concluded that none of the subjects was psychotic. Many responses to the DIS schizophrenia questions represented positive symptoms of PTSD (e.g., flashbacks).

The relationship of DIS findings to those derived from interviews that allow clinical judgment requires more investigation. It has been suggested that interviews administered by lay interviewers yield overestimates of comorbidity (22) and that clinician-administered structured diagnostic interviews are superior (23), but without a “gold standard” for psychiatric diagnosis, this remains unclear.

PATTERNS OF ONSET OF COMORBID DISORDER

Patterns of emergence of psychiatric disorders have been explored in clinical samples. In a sample of patients who were World War II and Vietnam combat veterans, similar patterns were found in the two groups: PTSD was primary (occurred first, just after the war in most patients), followed soon after by generalized anxiety disorder and alcoholism and later by phobias, depression, and panic disorder (24). In a sample of Vietnam veteran patients, PTSD was primary relative to mood and anxiety disorders (25). In another group of Vietnam veteran patients, PTSD symptoms were reported as beginning at the time of combat exposure, rapidly increasing over the initial postwar years, and then leveling off. Alcohol and substance abuse typically emerged with the onset of PTSD symptoms (26).

In the National Comorbidity Survey (4), PTSD was primary more often than not with respect to comorbid affective disorders and most substance use disorders. Male subjects reported alcohol abuse as more frequently occurring with or following the onset of PTSD, rather than predating it. Alcohol dependence was more likely to predate than co-occur with or follow onset of PTSD (27). PTSD was less likely to be primary with respect to comorbid anxiety disorders. In a community sample of women (5), PTSD was associated with increased risks of first-onset major depression and alcohol abuse/dependence. Also, the risk of major depression following PTSD was equal to the risk of major depression following other anxiety disorders.

Among Israeli combat veterans (7), affective disorders, particularly major depression, either appeared concurrently or were secondary to the onset of PTSD. In a sample of brushfire fighters (9), 11% of the subjects with complicated PTSD had another disorder at the time of the disaster, suggesting that 89% of the complicating disorders were either concurrent or secondary relative to the onset of PTSD. The presence of comorbid disorders, particularly panic and phobic disorders, made recovery from PTSD less likely.

PREDICTION OF COMPLICATED VERSUS UNCOMPLICATED PTSD

In a sample of Vietnam veterans, exposure to grotesque death and special combat assignments were the strongest predictors of complicated PTSD (28). Among Israeli combat veterans, predisposing factors did not predict development of the comorbid disorders significantly associated with PTSD (7). In a community sample of women, exposure to trauma per se did not increase the risk for disorders other than PTSD except for alcohol abuse/dependence (5). Brushfire fighters with uncomplicated PTSD reported the highest exposure to the disaster, suggesting that they required a more intense exposure to trigger PTSD; they may have had fewer of the vulnerability factors for comorbid disorders. The etiological process in persons with uncomplicated PTSD may be different from the process in those who have complicated PTSD (9).

Our study attempted to extend the findings summarized above by examining a community sample of men who had been exposed to extreme and prolonged wartime trauma, former prisoners of war (POWs). We used structured clinical interviews administered by experienced clinicians. We assessed current and lifetime axis I disorders, examined their relative times of onset, and explored the relation between exposure to trauma and the development of complicated versus uncomplicated PTSD. We hypothesized that the relative frequencies and onset patterns of the comorbid disorders in subjects with PTSD would be comparable to the frequencies and patterns observed in other trauma-exposed community samples. We also hypothesized that subjects who developed complicated PTSD would have suffered greater exposure to trauma than those who developed uncomplicated PTSD.

METHOD

The subjects were community-residing former POWs who completed diagnostic interviews and psychodiagnostic testing at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Minneapolis between 1991 and 1994. More details about the study group and test results are reported elsewhere (29, 30). All subjects were male. Their median age was 71 years, and their median education level was 12 years. Two were Native American, one Hispanic, and the rest white. Only 7% were involved in mental health care at the time of their recruitment for the study; even fewer were seeking compensation at the time of their participation. Of 344 potential subjects, 262 (76%) completed assessments. As POWs, they were held by Japan (N=56), Germany (N=191), and North Korea (N=15). After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

All subjects were administered the SCID PTSD module (31) and the non-patient version of the SCID (17). The interviewers were four psychologists with 2 to 14 years (mean=8 years) of experience in psychodiagnosis and assessment of combat-related PTSD. Although there were no reinterviews to estimate the stability of the diagnostic ratings, estimates of interjudge agreement were made. Among the lifetime PTSD cases, two interviews were directly observed by a second rater, and five interviews were taped and independently reviewed by two additional raters, allowing three pairs of observations for these cases. There were no disagreements over the presence or absence of current or lifetime axis I disorders (including PTSD) among these 23 pairs of ratings. There was one disagreement in rating the 36 emergence patterns of disorders comorbid with PTSD. The experience of torture/beatings was indexed by summation of responses to nine questions from a medical history self-report, yielding a score of 9 (no such experiences) to 27 (exposed to all nine forms of maltreatment). Combat exposure was self-reported by means of the Combat Exposure Scale (32). Social support was indexed through a sum of responses to items from the Social Reintegration Scale (33).

RESULTS

The mean number of lifetime axis I disorders was 2.3 (range=0–7). PTSD was the most prevalent disorder: 53.4% (N=140) of the subjects met criteria for a lifetime diagnosis, and 29.4% (N=77) met criteria for a current diagnosis.

Sixty-six percent of the men with lifetime PTSD reported one or more additional axis I disorders, versus 34% of those without PTSD (table 1). Inspection of the odds ratios’ 95% confidence intervals suggests that the disorders most strongly associated with lifetime PTSD were (in descending order) panic disorder, major depression, alcohol abuse/dependence, and social phobia. Phobias as such were more common than our figures suggest; many were related to traumatic experiences and thus were part of the PTSD and were excluded because of the diagnostic rules. Nonetheless, these phobias often impaired social and occupational functioning.

Thirty-four percent of the 140 subjects with lifetime PTSD had no other disorder (uncomplicated PTSD). If alcohol abuse/dependence is excluded, 59% had uncomplicated lifetime PTSD. Among the 140 lifetime cases of PTSD, only two cases of delayed onset were identified. All other PTSD cases were reported to have arisen during combat or captivity or within 6 months of release from prison camp.

Of the 185 subjects without current PTSD, 82.2% also were free of the other 33 current axis I disorders assessed by the SCID (table 2). Of the 77 with current PTSD, 54.5% had uncomplicated PTSD. Having current PTSD was associated with increased risk of having one or more additional axis I disorders, specifically (in descending order), panic disorder, dysthymia, social phobia, major depression, and generalized anxiety disorder. Although lifetime PTSD was associated with significantly increased risk of lifetime alcohol abuse/dependence (Pearson χ2=12.4, df=1, p<0.0005) (table 1), there was no association between current PTSD and current alcohol abuse/dependence (Pearson χ2=1.0, df=1, p=0.30). The presence of one or more comorbid lifetime disorders was unrelated to recovery from PTSD: 45.6% of the 48 subjects with uncomplicated lifetime PTSD did not meet the criteria for current PTSD, and 44.7% of the 92 with complicated lifetime PTSD did not meet the criteria for current PTSD (Pearson χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.91).

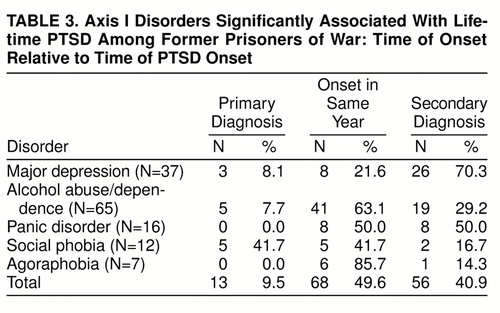

The disorders occurring more frequently among the subjects with lifetime PTSD had various dates of onset with respect to the time of PTSD onset, as presented in table 3. Five cases each of social phobia and alcohol abuse/dependence and three cases of major depression occurred before combat exposure and the onset of PTSD. Social phobia was most often primary or had an onset in the same year as PTSD. The primary disorders may or may not have been risk factors for PTSD development. Half of the panic disorder cases began in the same year as the onset of PTSD, and half were secondary. The onset of alcohol abuse/dependence was most often in the same year as the onset of PTSD, consistent with the POWs’ self-reported pattern of heavy drinking upon return to civilian life, which decreased over time. Twenty-six cases of secondary major depression occurred among the subjects with PTSD. These episodes arose as early as 1 year and as late as 48 years after the onset of PTSD. Overall, the onset of 91% of the comorbid disorders was either in the same year as the onset of PTSD or secondary to PTSD.

Table 4 presents the results of analyses of variance examining associations among lifetime disorders and factors predictive of PTSD. There were no significant mean differences in the predictor variables for those who had no lifetime disorders and those who had one or more lifetime disorders other than PTSD, so these categories were combined. Age at capture appears to be unrelated to the various diagnostic outcomes. The group with no PTSD reported significantly lower exposure to trauma than both PTSD groups. There were no significant differences between the uncomplicated and complicated PTSD groups.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with patterns observed in other studies (4, 5, 7, 9), PTSD was associated with increased risk of first onset of major depression. In our study group, major depression most often arose after the onset of PTSD (often many years later); case review suggested that it frequently arose following stressful life events. PTSD occurred in the same year or was the primary diagnosis more often than not with respect to comorbid alcohol abuse/dependence. For many subjects, alcohol abuse/dependence appeared to have been secondary to untreated PTSD and may have represented attempts at self-medication. PTSD was less likely to be the primary diagnosis relative to comorbid anxiety disorders, although even in these cases, the percentage of cases in which PTSD was primary was substantial (30%–60%). Among men in the National Comorbidity Survey (4), PTSD was primary with respect to all other comorbid disorders between 29% and 51% of the time.

PTSD may be causally related to comorbid disorders in several ways. Comorbid disorders may have arisen independently or been diagnosed as co-occurring because of symptom overlap. Emergence patterns (table 3) further suggest that some subjects with preexisting disorders may have been predisposed to develop PTSD. More frequently, comorbid disorders emerged following exposure to trauma because of shared risk factors, because of mutual (reciprocal) causality, or, in the case of disorders secondary to PTSD, as sequelae of PTSD, constituting a range of complications caused by distressing PTSD symptoms.

Results based on lifetime reports, such as ours, should be interpreted with caution. Prospective studies have shown that rates of forgetting previous disorders may be problematic in population surveys (34). Some additional lifetime disorders probably existed in our sample. Also, the proportion of complicated lifetime PTSD probably would have been somewhat higher if the SCID had allowed for diagnoses of lifetime dysthymia and generalized anxiety disorder. Subjects’ recall of symptoms and age at onset probably contained inaccuracies (i.e., after more than 40 years some might focus on the trauma as a referent point for all comorbidities). Conversely, their coping abilities mobilized during imprisonment may have led to a greater-than-usual awareness of their psychological state, past and present.

Comorbidity rates in this sample were lower than those in other reports based on community samples. This may in part explain the low rate of treatment seeking noted above, since comorbidity increases the likelihood of treatment seeking (7). The average level of trauma exposure appears to be higher in our sample than in other samples. We hypothesized that higher levels would be associated with uncomplicated PTSD, but this hypothesis was not supported at the group level by our data. It may still be true for certain individuals. In the absence of prospective studies using valid markers of premorbid vulnerability, hypotheses on this issue remain speculative.

Several other factors may have contributed to our findings of low comorbidity. Our sample is not comparable to random samples of the general population. Our subjects were selected in the first instance (entry into the military) for mental and physical health. They were less likely to have had psychiatric disorders before their exposure to trauma, thereby reducing comorbidity rates. Their resilience also may have contributed to low comorbidity; those with more comorbidity may have died earlier.

Uncomplicated PTSD may be more likely found in community samples such as ours in which trauma exposure has been severe. Also, the likelihood of detecting uncomplicated PTSD may be further increased when assessments are conducted by clinicians using structured diagnostic interviews. If we had used the DIS, we could have more closely compared our results with the results of other community surveys. The SCID probably yielded lower comorbidity rates than the DIS administered by a lay interviewer would have. Also, the SCID appears to yield higher estimates of PTSD prevalence than other methods of ascertainment (35). In the detection of PTSD, studies using DSM-III criteria and early versions of the DIS (1, 2, 9) may have yielded lower estimates than studies using DSM-III-R criteria and the SCID (6,8) or DSM-III-R criteria and recent revisions of the DIS (4,5).

Our findings support the validity of the diagnostic construct of PTSD, demonstrating that PTSD can be distinguished from comorbid disorders. Uncomplicated lifetime PTSD was found in a substantial minority (34%) of lifetime PTSD cases. Uncomplicated current PTSD was the rule, rather than the exception, being found in nearly 55% of current PTSD cases. These findings also indicate that uncomplicated PTSD may be more common than previous studies suggest, particularly in clinician-assessed subjects with histories of exposure to severe trauma.

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, Boston, Nov. 2–6, 1995Received Dec. 16, 1997; ; revisions received April 14 and May 21, 1998; accepted July 9, 1998. From the VA Medical Center, Minneapolis; and the Department of Psychology, Institute of Child Development, and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Engdahl, Psychology Service (116B), VA Medical Center, One Veterans Drive, Minneapolis, MN 55417; [email protected]. gov (e-mail). Supported by the VA and the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

|

|

|

|

1. Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630–1634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Davidson JRT, Hughes D, Blazer DG: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991; 21:713–721Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L: Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:81–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS: National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS): Description, Current Status, and Initial PTSD Prevalence Estimates: Final Report. Washington, DC, Veterans Administration, 1988Google Scholar

7. Skodol AE, Schwartz S, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE, Reiff M: PTSD symptoms and comorbid mental disorders in Israeli war veterans. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:717–225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Leonard AC: Chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and diagnostic comorbidity in a disaster sample. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:760–766Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. McFarlane AC, Papay P: Multiple diagnoses in posttraumatic stress disorder in the victims of natural disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:498–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Yehuda R, McFarlane AC: Conflict between current knowledge about posttraumatic stress disorder and its original conceptual basis. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1705–1713Link, Google Scholar

11. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Kessler RC, Eaton WW: DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:355–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG: Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168(suppl 30):17–30Google Scholar

14. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J (eds): National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version III: PHS Publication ADM-T-42-3. Rockville, Md, NIMH, 1981Google Scholar

15. Wittchen H-U: Critical issues in the evaluation of comorbidity of psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168(suppl 30):9–16Google Scholar

16. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

18. Wittchen H-U, Kessler RC, Zhao S, Abelson J: Reliability and clinical validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:95–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC: Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med (in press)Google Scholar

20. Frances A, Widiger T, Fyer MR: The influence of classification methods on comorbidity, in Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Edited by Maser JD, Cloninger CR. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 41–60Google Scholar

21. Escobar JI, Randolph ET, Puente G, Spiwak F, Asamen JK, Hill M, Hough RL: Post-traumatic stress disorder in Hispanic Vietnam veterans: clinical phenomenology and sociocultural characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis 1983; 171:585–596Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Keane TM, Wolfe J: Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder: an analysis of community and clinical studies. J Appl Soc Psychol 1990; 20:1776–1778Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Coyne JC: Self-reported distress: analog or ersatz depression? Psychol Bull 1994; 116:29–45Google Scholar

24. Davidson JRT, Kudler HS, Saunders WB, Smith RD: Symptom and comorbidity patterns in World War II and Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:162–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Mellman TA, Randolph CA, Brawman-Mintzer O, Flores LP, Milanes FJ: Phenomenology and course of psychiatric disorders associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1568–1574Link, Google Scholar

26. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Darnell A, Charney DS: Chronic PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans: course of illness and substance abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:369–375Link, Google Scholar

27. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Gleser GC: Multiple diagnoses in posttraumatic stress disorder: the role of war stressors. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:329–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Engdahl BE, Eberly RE, Blake JD: The assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in World War II veterans. Psychol Assessment 1996; 8:445–449Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Engdahl B, Dikel TN, Eberly R, Blank A Jr: Posttraumatic stress disorder in a community sample of former prisoners of war: a normative response to severe trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1576–1581Link, Google Scholar

31. Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Version Modified for Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, April 1, 1987Google Scholar

32. Keane TM, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM, Zimmerling RT, Taylor KL, Moira CA: Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychol Assessment 1989; 1:53–55Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Laufer RS, Yaeger T, Frey-Wouters E, Donellan J: Post-war trauma: social and psychological problems of Vietnam veterans and their peers, in Legacies of Vietnam, vol III. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1981Google Scholar

34. Wilhelm K, Parker G: Sex differences in lifetime depression rates: fact or artifact? Psychol Med 1994; 24:97–111Google Scholar

35. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank, JA, Jordan BK, Hough RL, Marmar CR, Weiss DS: Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: prospects and pitfalls from recent studies of Vietnam veterans. Psychol Assessment 1991; 3:547–560Crossref, Google Scholar