Family History of Suicidal Behavior and Mood Disorders in Probands With Mood Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: First-degree relatives of persons with mood disorder who attempt suicide are at greater risk for mood disorders and attempted or completed suicide. This study examined the shared and distinctive factors associated with familial mood disorders and familial suicidal behavior. METHOD: First-degree relatives’ history of DSM-IV–defined mood disorder and suicidal behavior was recorded for 457 mood disorder probands, of whom 81% were inpatients and 62% were female. Probands’ lifetime severity of aggression and impulsivity were rated, and probands’ reports of childhood physical or sexual abuse, suicide attempts, and age at onset of mood disorder were recorded. Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out to identify predictors of suicidal acts in first-degree relatives. RESULTS: A total of 23.2% of the probands with mood disorder who had attempted suicide had a first-degree relative with a history of suicidal behavior, compared with 13.2% of the probands with mood disorder who had not attempted suicide (odds ratio=1.99, 95% CI=1.21–3.26). Thirty percent (30.8%) of the first-degree relatives with a diagnosis of mood disorder also manifested suicidal behavior, compared with 6.6% of the first-degree relatives with no mood disorder diagnosis (odds ratio=6.25, 95% CI=3.44–11.35). Probands with and without a history of suicide attempts did not differ in the incidence of mood disorder in first-degree relatives (50.6% versus 48.1%). Rates of reported childhood abuse and severity of lifetime aggression were higher in probands with a family history of suicidal behavior. Earlier age at onset of mood disorder in probands was associated with greater lifetime severity of aggression and higher rates of reported childhood abuse, mood disorder in first-degree relatives, and suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives. CONCLUSIONS: Risk for suicidal behavior in families of probands with mood disorders appears related to early onset of mood disorders, aggressive/impulsive traits, and reported childhood abuse in probands. Studies of such clinical features in at-risk relatives are under way to determine the relative transmission of these clinical features.

Suicidal behavior is more common in the relatives of suicide attempters, compared to nonattempter psychiatric comparison subjects. This finding has two implications. First, relatives of suicide attempters can be identified as an at-risk population for suicidal behavior and thus a potential group to target for intervention against future suicidal acts. Second, because suicidal behavior aggregates in families, the factors—both genetic and nongenetic—that are responsible for familial transmission of suicidal behavior should be discernible and may be targets for preventive therapeutic intervention. In the study reported here, we investigated factors beyond mood disorder that may account for familial suicidal behavior.

Suicidal behavior is closely associated with the presence of mood disorder. However, there is evidence that the higher rate of suicidal behavior in relatives of suicide attempters cannot be fully explained by higher rates of mood disorders in those same relatives (1). Genetic factors contribute to the risk for suicidal behavior, and evidence suggests this contribution is over and above the genetic contribution to mood disorder transmission. Twin studies provide evidence for the heritability of suicidal behavior, with reports that genetic factors predicted 17%–45% of the variance in suicidal behavior (2, 3) and that genetic and shared environmental influences together accounted for 35%–75% of the variance in risk of suicidal behavior (4).

Studies of children and adolescents also found higher rates of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives of proband suicide attempters (5, 6) and probands who die by suicide (7, 8) than in nonsuicidal community or psychiatric comparison subjects. Moreover, the incidence of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives remains higher in proband suicide attempters and those who die by suicide in analyses that adjust for the effect of first-degree relatives’ axis I disorders; these findings indicate that there are other factors, in addition to axis I psychiatric diagnosis, that contribute to familial liability for suicidal acts (5–7). A study of suicide in Old Order Amish pedigrees over a 100-year period supported this conclusion in finding that although there was a significant loading of mood disorders in families that had suicides, other families with comparably high rates of mood disorders had no history of suicide (9).

We previously reported that offspring of depressed suicide attempters have a sixfold greater risk of suicide attempts, compared to offspring of depressed nonattempters (1). That study identified a role for childhood abuse history and impulsive aggression in the transmission of suicidal behavior and found that early onset of mood disorder was related to suicide attempt. It also documented an inverse correlation between impulsivity/aggression and age at onset of mood disorder in probands that warranted testing in a larger, older group of subjects. That study had the advantage of direct assessments of both depressed probands and their offspring, but it had a limited number of subjects (N=136 probands). The present study has considerably more subjects (N=457) and is, to our knowledge, the largest study to date examining clinical factors in relation to familial suicidal behavior in probands with mood disorders. The purpose of this study is to determine the relative rates of familial mood disorder and suicidal behavior, defined by their presence in at least one first-degree relative, and to identify proband characteristics associated with familial mood disorder and/or suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives. On the basis of findings in adult studies (10, 11) and early results from a study of offspring of depressed adults (1, 12), we hypothesized that factors such as aggressive/impulsive traits and reported childhood abuse would contribute to familial suicidal behavior.

Method

Probands

Probands were recruited from the research inpatient and outpatient clinics at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, where they had been referred for evaluation of a mood disorder. Proband lifetime mood disorder diagnosis (major depressive episode, bipolar disorder, dysthymia) was determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (13). All subjects gave written informed consent, as required by the applicable institutional review boards.

The majority of the 457 probands were female (61%) and were evaluated and then treated initially as inpatients (81.8%). The high proportion of inpatients reflects the fact that the study group was enriched with suicide attempters who had often made suicide attempts in the context of current major depression and required hospitalization. Because many of these subjects were inpatients, we recruited inpatient nonattempters as well. Approximately one-half (51.9%) of all probands had made at least one suicide attempt. For initial analyses we defined two groups using the criterion of proband lifetime suicide attempt status: attempter and nonattempter.

First-Degree Relatives

We defined mother, father, full brothers and sisters, and offspring of each proband as first-degree relatives. Probands had a mean of 5.6 first-degree relatives (SD=3.2). Probands provided information on the psychiatric history of their relatives to an interviewer who completed a genogram. In the majority of cases (N=419, 91%), at least one other relative was also interviewed regarding family history. Family history of suicidal behavior was rated as present where probands reported at least one first-degree relative with a suicidal act. A suicidal act was defined as either a suicide attempt (a self-injurious act with some intent to end one’s life) or a completed suicide.

Assessment Instruments

All probands were age 17 years or older and were assessed for the presence of lifetime and current DSM-IV axis I psychiatric disorders by using the SCID (13). First-degree relatives who were not directly interviewed were assessed with the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (with criteria modified for DSM-IV) (14) on the basis of data obtained from the proband and, in the majority of cases, at least one other biological relative. History of suicidal behavior was assessed with the Columbia Suicide History Form (15). Lethality of proband suicide attempts was assessed with the Lethality Rating Scale (16), on which attempts are rated from 0 (no medical damage) to 8 (death). Attempts with a rating of ≥4, the point at which medical treatment for the consequences of the attempt is required, were considered high-lethality attempts.

Proband lifetime aggression was rated with the 11-item Brown-Goodwin Lifetime History of Aggression (17), and impulsivity was rated with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (18). A history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse was assessed with screening questions in the baseline demographic and clinical history and in the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) section of the SCID. All interviewers were at least master’s-level clinicians or psychiatric nurses who received extensive training in the administration of semistructured interviews. For clinical and demographic measures for which data were not available on all subjects, the number of subjects assessed is noted in the relevant table.

Statistical Methods

Demographic and clinical variables were compared in suicide attempter and nonattempter probands by using Student’s t test for continuous variables and the chi-square statistic or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Nonparametric data were tested with the Mann-Whitney test. In additional analyses, chi-square tests and t tests were used to compare probands with and without suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives, to compare probands with and without mood disorder in first-degree relatives, and to explore associations between proband childhood abuse, age at onset of major depression, and aggression as possible pathways for familial suicidal behavior. Pearson product-moment correlation was used to test for a linear relationship between age at onset of proband mood disorder and aggression scores. We constructed four multinomial regression models to examine the relationship between suicidal acts in first-degree relatives, mood disorder in first-degree relatives, and suicide attempts in probands and the possible mediating roles of proband aggression and history of childhood abuse, as suggested in the findings of our univariate analyses. In all four models the dependent variable was suicidal acts in first-degree relatives. In the first model, the independent variables were mood disorders in first-degree relatives and suicide attempts in probands. In the second model, the independent variables were mood disorders in first-degree relatives and aggression and suicide attempts in probands. The independent variables in the third model were mood disorders in first-degree relatives and childhood abuse and suicide attempts in probands. In the final model, the independent variables were mood disorders in first-degree relatives and suicide attempts, aggression, childhood abuse, and age in probands. The results are reported as means and standard deviations. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Characteristics of Proband Suicide Attempters and Nonattempters

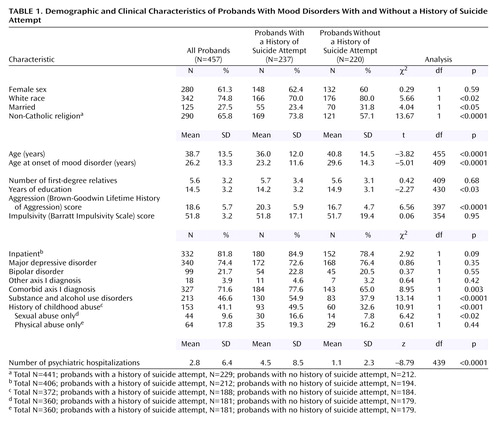

Table 1 presents a comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of proband suicide attempters and nonattempters. Compared to nonattempter probands, attempter probands were younger; were less likely to be Catholic, white, or married; and had slightly fewer years of education. Almost three-quarters of the probands had a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder (N=340, 74.4%). The spectrum of mood disorders was comparable in proband attempters and nonattempters. Seventy-one percent (71.6%, N=327) of all probands had an additional comorbid axis I diagnosis (46.6% [N=213], alcohol and substance use disorders; 33.1% [N=72], dysthymia; 30.4% [N=66], panic disorder; 16.5% [N=36], PTSD; and 11.9% [N=26], bulimia). Probands with bipolar disorder were less likely to have comorbid dysthymia and more likely to have comorbid panic disorder, compared with probands with major depressive disorder (data not shown). Probands who attempted suicide were more likely than nonattempter probands to have a comorbid axis I diagnosis and a substance or alcohol use disorder.

Attempter probands were on average 6 years younger than nonattempter probands at the time of mood disorder onset and reported four times as many psychiatric hospitalizations. Probands who attempted suicide were more aggressive, but not more impulsive, and more likely to report a history of childhood sexual abuse, and childhood abuse in general, than probands who had not attempted suicide.

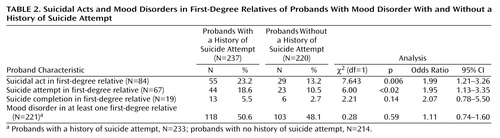

Familial Suicidal Behavior and Proband Clinical Characteristics

Table 2 gives details about suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives in relation to probands’ suicide attempt status. Probands who attempted suicide were more likely than nonattempter probands to have a first-degree relative with at least one suicidal act (attempt or completion). Significantly more attempter probands than nonattempter probands had at least one first-degree relative who had made a suicide attempt. However, there was no significant association between suicide completions in first-degree relatives and suicide attempts in probands. The small number of first-degree relatives who died by suicide limited statistical power, but, as with suicide attempts and suicidal acts in first-degree relatives, there was an almost twofold higher rate of completed suicide in first-degree relatives of proband suicide attempters, compared to nonattempters (5.5% [N=13] versus 2.7% [N=6]). There was no difference in the rate of suicidal acts in first-degree relatives between proband suicide attempters with low-lethality attempts and those with high-lethality attempts (22% [N=27] versus 15% [N=16]) (χ2=1.40, df=1, p=0.24). Relatives with a mood disorder had a significantly higher rate of suicidal acts, compared with relatives with no mood disorder (30.8% [N=68 of 221] versus 6.6% [N=15 of 226]) (χ2=43.03, df=1, p<0.0001; odds ratio=6.25, 95% confidence interval=3.44–11.35).

Probands with a history of suicide attempt in first-degree relatives had a significantly younger age at onset of mood disorder than those with no history of suicide attempt in first-degree relatives (mean=22.0 years, SD=10.4, versus mean=27.0 years, SD=13.7) (t=–2.7, df=409, p=0.006). Age at mood disorder onset was not significantly earlier in probands with first-degree relatives who died by suicide than in probands with no history of completed suicide in first-degree relatives (mean=32.0 years, SD=13.0, versus mean=26.0 years, SD=13.3) (t=1.7, df=408, p=0.09). It is noteworthy that, unlike the younger age at mood disorder onset in probands with first-degree relatives who attempted suicide, older age at mood disorder onset in probands was associated with suicide completion in first-degree relatives. This difference explains the nonsignificant finding with respect to proband age at mood disorder onset in analysis in which attempts and completions in first-degree relatives were considered together as suicidal acts (t=–1.7, df=409, p=0.09).

Probands with first-degree relatives who had a history of suicidal acts had higher lifetime aggression scores (Brown-Goodwin Lifetime History of Aggression) than probands with no first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal acts (mean=20.1, SD=5.6, versus mean=18.2, SD=5.7) (t=2.5, df=397, p<0.02) and a higher rate of comorbid alcohol and substance use disorders (59.5% [N=50] versus 43.8% [N=163]) (χ2=6.79, df=1, p=0.009) but similar rates of other axis I comorbidity (21.2% [N=46] versus 15.8% [N=38]) (χ2=2.19, df=1, p=0.14). Within the proband suicide attempter group there was no difference in lifetime aggression score between those with or without a family history of suicidal acts (mean=21.0, SD=5.4, versus mean=20.1, SD=6.1) (t=0.92, df=209, p=0.36). Lifetime impulsivity, measured with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale, was significantly higher in probands with first-degree relatives with a history of suicide attempts (mean=56.6, SD=14, versus mean=50.9, SD=18) (t=2.09, df=354, p<0.04) but not in probands with first-degree relatives who died by suicide (mean=49.1, SD=21, versus mean=51.9, SD=18) (t=–0.58, df=354, p=0.56) or in probands with first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal acts (both attempted and completed suicide) (mean=55.1, SD=16, versus mean=50, SD=18) (t=1.60, df=354, p=0.11). Probands who reported a history of childhood abuse were more likely to have first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal acts (26.1% [N=40] versus 14.1% [N=31]) (χ2=8.30, df=1, p=0.004). The rates of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives did not differ in probands with physical, compared to sexual, abuse histories (data not shown).

Familial Mood Disorder and Proband Clinical Characteristics

The rates of mood disorders in first-degree relatives of suicide attempter and nonattempter probands were high and comparable: 50.6% (N=118 of 233) and 48.1% (N=103 of 214), respectively (Table 2). Probands with first-degree relatives with a history of mood disorder had a significantly earlier age at onset of mood disorder than those without first-degree relatives with a history of mood disorder (mean=24.3 years, SD=12.1, versus mean=28.5 years, SD=14.2) (t=3.1, df=400, p=0.002). There were no differences between probands with or without first-degree relatives with mood disorders in lifetime impulsivity score (mean=53.4, SD=18, versus mean=49.7, SD=18) (t=1.89, df=347, p=0.06), aggression score (mean=18.6, SD=5.6, versus mean=18.6, SD=5.8) (t=–0.17, df=391, p=0.86), or reported history of childhood abuse (44% [N=100] versus 36% [N=50]) (χ2=2.05, df=1, p=0.15). Among probands with first-degree relatives with a history of mood disorder, those who reported a history of childhood abuse were more likely to report physical rather than sexual abuse (66% [N=47] versus 45% [N=32]) (χ2=4.50, df=1, p<0.04). Unlike familial suicidal behavior, rates of comorbid substance and alcohol use disorders did not distinguish probands with and without a first-degree relative with mood disorder (data not shown).

Proband Childhood Abuse, Aggression, and Age at Onset of Mood Disorder

Forty-one percent (41%, N=153 of 372) of all probands reported a history of childhood abuse. Abused probands had higher lifetime aggression scores than those with no reported abuse history (mean=19.5, SD=5.6, versus mean=17.0, SD=5.0) (t=4.22, df=334, p<0.0001) but similar lifetime impulsivity scores (mean=53.8, SD=17, versus mean=50.4, SD=19) (t=1.59, df=313, p=0.11). Lifetime aggression scores were higher in proband suicide attempters who reported a history of childhood abuse than in proband attempters with no abuse history (mean=20.7, SD=5.7, versus mean=18.2, SD=5.3) (t=2.87, df=169, p=0.005). Proband aggression, impulsivity, and age at onset of mood disorder did not differ in probands with physical, compared to sexual, abuse histories (data not shown).

Younger age at mood disorder onset was associated with a history of childhood abuse (mean=23.8 years, SD=13, versus mean=26.8 years, SD=12) (t=–2.30, df=343, p<0.02). A modest, but significant, negative correlation was found between age at onset of mood disorder and lifetime aggression score (Pearson’s r=–0.17, N=368, p<0.02), meaning that younger age at onset of mood disorder was associated with more lifetime aggression.

Regression Analyses

All four multivariate models were highly significant predictors of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives of probands with mood disorders (χ2=44.5–54.03, df=2–5, p<0.0001), and in all four models mood disorder in first-degree relatives was a significant independent predictor of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives (p<0.0001). In the first model, proband suicide attempt was an independent predictor (β=0.75, Wald χ2=7.86, df=1, p=0.005). In the second model, which included the aggression score, the results for proband suicide attempt (β=0.53, Wald=3.31, df=1, p=0.07) and aggression score (β=0.05, Wald=3.65, df=1, p=0.06) approached significance, suggesting a mediating effect of aggression on the effect of proband suicide attempt with respect to predicting suicidal acts in first-degree relatives. The third model differed from the first model by the addition of proband history of childhood abuse, which was predictive of suicidal acts in first-degree relatives (β=0.73, Wald=6.51, df=1, p<0.02) but had nonsignificant results for proband suicide attempt (β=0.48, Wald=2.75, df=1, p=0.10), indicating that the relationship between proband suicidal behavior and suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives may also be mediated by proband childhood abuse. In the final model, which included both aggression score and proband history of childhood abuse, proband history of childhood abuse was significant, but proband age, suicide, attempt, and aggression were not (Table 3).

Discussion

Familial Transmission of Suicidal Behavior and Mood Disorder

Studies have found that 12%–20% of suicide attempters with mood disorders report a history of suicide attempt in first-degree relatives (1, 5, 7, 10, 19), and 8%–22% report a family history of suicide completion in first- or second-degree relatives (20–24). We found that 23.2% of probands with a mood disorder who attempted suicide had at least one first-degree relative with a history of suicidal acts, almost twice the rate of nonattempter probands with a mood disorder. This finding is consistent with reports that suicide attempters with mood disorders have between a 1.5-fold and sixfold higher rate of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives, compared with subjects with mood disorders who do not attempt suicide (5, 7, 10, 19, 24).

Mood disorders are a major risk factor for suicidal behavior. This study found that probands’ first-degree relatives with a mood disorder had a fourfold higher rate of suicidal behavior, compared to relatives with no mood disorder, confirming the important role of mood disorders in the occurrence of suicidal behavior. However, the results of our previous study of a high-risk cohort of suicide attempters with major depressive disorder and their offspring suggested that although the transmission of mood disorder is an important component of familial transmission of suicidal behavior, it is not sufficient to account fully for familial transmission of suicidal behavior (1).

Both genetic and nongenetic factors play a role in the familial transmission of suicidal behavior. Twin (2–4) and adoption (25) studies have provided evidence of a genetic contribution to the familial transmission of suicidal behavior in community samples. A strong association between suicidal behavior and mood disorders is noted in these studies; however, all found evidence that transmission of suicidal behavior, to some extent, requires factors in addition to transmission of mood disorder (2–4, 25). Likewise, the majority of family studies have observed that suicidal behavior aggregates in families somewhat independently of familial transmission of mood disorder (5, 9, 19, 20, 23, 26, 27), suggesting the existence of other predisposing factors.

In support of the hypothesis that mood disorders and the predisposition to suicidal acts are transmitted independently, the present study of first-degree relatives of probands with mood disorders found high, but comparable, rates of mood disorders in first-degree relatives of both suicide attempter probands and nonattempter probands. However, probands who attempted suicide were more likely to have first-degree relatives with a history of suicidal behavior than were probands who did not attempt suicide. Thus, this study demonstrates, in concurrence with the literature, that familial mood disorder alone does not explain familial aggregation of suicidal behavior. We hypothesize that there must also be a familial transmission of a diathesis for suicidal behavior.

Familial Mood Disorder and Suicidal Behavior and Age at Mood Disorder Onset

We found that suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives of probands with mood disorders is clearly linked to mood disorder in the relatives, consistent with longitudinal prospective studies showing that suicide attempts occur during episodes of major depression (11). There have been few studies of the age at onset of depressive disorder in relation to family history of suicidal behavior. Winokur et al. (28) found that significantly more parents of probands with early-onset depressive illness (age <40 years) had committed suicide, compared with parents of probands with late-onset depressive illness. That study, and studies of familial transmission of mood disorder, found associations between early-onset mood disorder and higher rates of family history of mood disorder (28–34), comorbid anxiety disorder (29, 32), alcoholism (29, 32, 34), and sociopathy (34). Such psychopathology carries a higher risk of suicidal behavior and may, in part, explain the finding in the present study that higher rates of suicidal behavior occur in families of probands with an earlier onset of mood disorder.

In this study, probands who reported a history of mood disorder in first-degree relatives had an earlier age at onset of mood disorder than those with no family history of mood disorders. Earlier age at mood disorder onset also occurred in probands with a family history of suicide attempt, but not suicide completion. However, the small number of completed suicides in first-degree relatives limited statistical power. In this study, probands with a younger age at mood disorder onset were at higher risk for suicidal behavior. They were also more likely to report childhood abuse and were more aggressive than probands with later onset of mood disorder; both characteristics are potential markers of risk for suicidal behavior, and both are familial. Transmission of aggressive/impulsive traits, perhaps related to childhood abuse, may contribute to familial suicidal behavior; this interpretation is consistent with the findings in our previous study of a high-risk cohort (1).

Lifetime Aggression, Childhood Abuse, and Familial Suicidality

Aggressive/impulsive behavior has been associated with suicidal behavior in mood disorders (19, 35), and in this study, probands with mood disorder who attempted suicide had higher lifetime aggression scores than probands with mood disorder who did not attempt suicide. Few studies have examined aggression with respect to transmission of suicidal behavior. Linkowski et al. (24) noted that the offspring of largely violent suicide attempters made more, and more frequently violent, suicide attempts. However, they did not quantify aggression. Pfeffer et al. (6) found that children who engage in suicidal behavior have a higher incidence of first-degree relatives with assaultive behavior, but they provided no data on levels of aggression in those child attempters. In our high-risk familial transmission study, we reported that individuals with a family history of suicidal behavior have higher aggression ratings and that aggression may be a heritable trait (1). Although the current study did not examine intergenerational transmission of aggression, we did find evidence that aggression predicts familial suicidal behavior independently of mood disorder in first-degree relatives.

The role of aggression in familial suicidal behavior is complex. In this study, although both proband suicide attempt and a family history of suicidal acts were independently associated with higher levels of aggression, among probands with a family history of suicidal behavior there was no difference in aggression ratings between suicide attempters and nonattempters. Thus, aggression is associated with suicide attempt in the probands and with a family history of suicidal acts, but it is not the only factor determining the occurrence of suicidal behavior in families. Increased aggression/impulsivity has been associated with substance and alcohol use disorders (36), which have also been shown to be familial (37), and to be associated with suicidal behavior in mood disorders (38). In the current study, comorbid alcohol or substance use disorder was associated with both proband suicide attempt and family history of suicidal behavior, suggesting it may be a contributory factor, either independently or in the context of increased aggression/impulsivity, to familial suicidal risk.

The results of our regression models suggest that the role of aggression in the familial aggregation of suicidality may be mediated by childhood abuse, which, along with other adverse child rearing conditions, has been shown to increase liability for suicidal behavior (39, 40). A study by this group found that subjects who reported an abuse history were more likely to have made a suicide attempt and had significantly higher impulsivity and aggression scores than those who did not report an abuse history (41). Moreover, we previously reported that both sexual abuse and aggression may be transmitted from parents to offspring and that the offspring of abused suicide attempters were more likely to make a suicide attempt than the offspring of suicide attempters who had not been abused (1).

The design of the present study did not permit a description of direct parent-offspring transmission of abuse, suicidal behavior, or aggression. However, we did observe a similar constellation of these three factors in relation to familial aggregation of suicidal acts. In the current study, proband-reported childhood abuse was associated with more proband aggression, suicidal behavior, and a family history of suicidal behavior. Our regression models showed that a history of childhood abuse in the probands not only independently predicted suicidal acts in first-degree relatives but also may have had a mediating role with respect to both proband aggression and suicide attempts in relation to familial suicidal behavior. In the current study, a history of abuse appears to intensify aggression in various contexts. For example, on the whole, suicide attempters were more aggressive than nonattempters. However, attempters who had been abused had significantly higher lifetime aggression scores than nonabused attempters. Likewise, probands with a family history of suicidal behavior were more aggressive than those with no such history. Yet among probands with a family history of suicidal behavior, those who had been abused were more aggressive than those who had not.

These findings, and those of other family studies (1, 7, 41), suggest two potential pathways whereby childhood abuse plays a role in the familial transmission of suicidality. First, childhood abuse appears to confer an increased susceptibility to earlier onset of mood disorder and thus more exposure to the stressor of depressive episodes, which are known to be a major risk factor for suicidal behavior (42). Second, childhood abuse appears to increase the likelihood of developing aggressive/impulsive traits, which also increase risk for suicidal behavior. Aggression could lead to more childhood abuse and could be worsened by abuse. Further longitudinal research is required to examine the nature of the interaction between aggression and abuse and their relationship to familial transmission of both mood disorder and suicidal behavior from both genetic and environmental developmental perspectives.

Limitations

Probands were largely inpatients with a high incidence of suicidal behavior and thus represent an acutely ill cohort. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to all patients with mood disorders. In addition, the majority of probands were female, and the results need further evaluation in male probands. In many cases, we were able to interview at least one first-degree relative to obtain family history, but we were not always able to do so. The family history method has been shown to provide adequate diagnostic sensitivity; however, it has limitations (43). Given that all the probands had a mood disorder and that we had additional data from relatives, the possibility of under- or overreporting of events such as suicidal behavior is lessened, but it cannot be ruled out. Also, individuals who have attempted suicide may be more aware of suicidal behavior in other family members, which hypothetically could lead to more complete information. However, this relationship has not been demonstrated and is made less likely in the current study by the inclusion of family history data from probands’ relatives. The cross-sectional nature of the study and the lack of direct examination of all first-degree family members of the probands limit the data and prevent determination of the time of onset of aggressive traits and mood disorder in relation to childhood abuse. Such questions can be answered only by longitudinal follow-up of at-risk offspring.

Conclusions

We have shown that familial suicidal behavior is not solely attributable to familial mood disorder. A cluster of factors are associated with a family history of suicidal behavior, including earlier onset of depression, reported childhood abuse, and higher levels of aggression. Together, these factors elevate the risk of familial suicidal behavior. Further research is required to clarify the temporal relationship and interaction between these factors and identify potential points for therapeutic intervention.

We have previously hypothesized a stress-diathesis model of suicidal behavior whereby a major depressive episode is an acute stressor and the diathesis includes aggressive/impulsive traits as well as a pessimistic trait, characterized by more suicidal ideation, subjective depression, hopelessness, and reporting of fewer reasons for living, despite comparable objective severity of depression and life events. We have shown that this model has predictive properties (11). Our current finding supports the model by showing that familial suicidal behavior depends heavily on familial mood disorders, but because mood disorders can be present in families without suicidal behavior, it also suggests that other factors, such as the diathesis described in our model, contribute to suicide risk.

|

|

|

Received Feb. 13, 2004; revision received July 27, 2004; accepted Sept. 13, 2004. From the Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Mann, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., Box 42, New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-62185, MH-56390, MH-48514, and MH-56612 and by the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

1. Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, Zelazny J, Brodsky B, Bridge J, Ellis S, Salazar JO, Mann JJ: Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: risk for suicidal behavior in offspring of mood-disordered suicide attempters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:801–807Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Bierut L, Dinwiddie SH, Slutske WS, Dunne MP, Martin NG: Suicidal behaviour: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychol Med 1998; 28:839–855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Glowinski AL, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, Jacob T, True MR, Eisen SA: A twin study of genetic and environmental influences on suicidality in men. Psychol Med 2002; 32:11–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Glowinski AL, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Fu Q, Madden PAF, Reich W, Heath AC: Suicide attempts in an adolescent female twin sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1300–1307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Johnson BA, Brent DA, Bridge J, Connolly J: The familial aggregation of adolescent suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 97:18–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pfeffer CR, Normandin L, Kakuma T: Suicidal children grow up: suicidal behavior and psychiatric disorders among relatives. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:1087–1097Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Brent DA, Bridge J, Johnson BA, Connolly J: Suicidal behavior runs in families: a controlled family study of adolescent suicide victims. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1145–1152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D: Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1155–1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Egeland JA, Sussex JN: Suicide and family loading for affective disorders. JAMA 1985; 254:915–918Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:181–189Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, Mann JJ: Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1433–1441Link, Google Scholar

12. Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, Zelazny J, Brodsky B, Firinciogullari S, Ellis SP, Mann JJ: Peripubertal suicide attempts in offspring of suicide attempters with siblings concordant for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1486–1493Link, Google Scholar

13. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1994Google Scholar

14. Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G: The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1229–1235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ: Risk factors for suicidal behavior: the utility and limitations of research instruments, in Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Edited by First MB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, pp 103–130Google Scholar

16. Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M: Classification of suicidal behaviors, I: quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:285–287Link, Google Scholar

17. Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF: Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979; 1:131–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Barratt ES: Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychol Rep 1965; 16:547–554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Mann JJ: Major depression and the risk of attempted suicide. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:173–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Roy A: Family history of suicide in manic-depressive patients. J Affect Disord 1985; 8:187–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Pitts FN, Winokur G: Affective disorder, III: diagnostic correlates and incidence of suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis 1964; 139:176–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Brodie HK, Leff MJ: Bipolar depression—a comparative study of patient characteristics. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 127:1086–1090Link, Google Scholar

23. Roy A: Family history of suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:971–974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Linkowski P, De Maertelaer V, Mendlewicz J: Suicidal behaviour in major depressive illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1985; 72:233–238Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Schulsinger F, Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Wender PH: A family study of suicide, in Origin, Prevention, and Treatment of Affective Disorders Edited by Schou M, Stromgren E. New York, Academic Press, 1979, pp 277–287Google Scholar

26. Runeson B, Åsberg M: Family history of suicide among suicide victims. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1525–1526Link, Google Scholar

27. Tsuang MT: Risk of suicide in the relatives of schizophrenics, manics, depressives, and controls. J Clin Psychiatry 1983; 44:396–400Medline, Google Scholar

28. Winokur G, Morrison J, Clancy J, Crowe R: The Iowa 500: familial and clinical findings favor two kinds of depressive illness. Compr Psychiatry 1973; 14:99–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Rende R, Weissman M, Rutter M, Wickramaratne P, Harrington R, Pickles A: Psychiatric disorders in the relatives of depressed probands, II: familial loading for comorbid non-depressive disorders based upon proband age of onset. J Affect Disord 1997; 42:23–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. McGuffin P, Katz R, Bebbington P: Hazard, heredity and depression: a family study. J Psychiatr Res 1987; 21:365–375Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Merikangas KR, Leckman JF, Prusoff BA, Caruso KA, Kidd KK, Gammon GD: Onset of major depression in early adulthood: increased familial loading and specificity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:1136–1143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Weissman MM, Merikangas KR, Wickramaratne P, Kidd KK, Prusoff BA, Leckman JF, Pauls DL: Understanding the clinical heterogeneity of major depression using family data. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:430–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Baron M, Mendlewicz J, Klotz J: Age-of-onset and genetic transmission in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1981; 64:373–380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Mendlewicz J, Baron M: Morbidity risks in subtypes of unipolar depressive illness: differences between early and late onset forms. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139:463–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Oquendo MA, Waternaux C, Brodsky B, Parsons B, Haas GL, Malone KM, Mann JJ: Suicidal behavior in bipolar mood disorder: clinical characteristics of attempters and nonattempters. J Affect Disord 2000; 59:107–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Branchey L, Branchey M, Shaw S, Lieber CS: Depression, suicide, and aggression in alcoholics and their relationship to plasma amino acids. Psychiatry Res 1984; 12:219–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kendler KS, Davis CG, Kessler RC: The familial aggregation of common psychiatric and substance use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: a family history study. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:541–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Mezzich J, Cornelius MD, Fabrega HF Jr, Ehler JG, Ulrich RF, Thase ME, Mann JJ: Disproportionate suicidality in patients with comorbid major depression and alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:358–364Link, Google Scholar

39. Molnar BE, Berkman LF, Buka SL: Psychopathology, childhood sexual abuse and other childhood adversities: relative links to subsequent suicidal behaviour in the US. Psychol Med 2001; 31:965–977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Fergusson DM, Beautrais AL, Horwood LJ: Vulnerability and resiliency to suicidal behaviours in young people. Psychol Med 2003; 33:61–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Brodsky BS, Oquendo M, Ellis SP, Haas GL, Malone KM, Mann JJ: The relationship of childhood abuse to impulsivity and suicidal behavior in adults with major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1871–1877Link, Google Scholar

42. Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Ellis SP, Sackeim HA, Mann JJ: Inadequacy of antidepressant treatment for patients with major depression who are at risk for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:190–194Abstract, Google Scholar

43. Andreasen NC, Rice J, Endicott J, Reich T, Coryell W: The family history approach to diagnosis: how useful is it? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:421–429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar