Inadequacy of Antidepressant Treatment for Patients With Major Depression Who Are at Risk for Suicidal Behavior

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to determine whether suicide attempters with major depression received more intensive antidepressant treatment than depressed patients who had not attempted suicide. METHOD: One hundred eighty inpatients who met DSM-III-R criteria for a major depressive episode according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R were enrolled in the study. All patients were assessed for lifetime history of suicide attempts. Depressive symptoms at the index hospitalization were assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. Strength of antidepressant treatment over the 90 days preceding the hospitalization was scored by using the Antidepressant Treatment History Form. RESULTS: A large majority of the depressed patients with a history of suicide attempts, who were at higher risk for future suicide and suicide attempts, received inadequate treatment. Similarly, most of the depressed patients at lower risk for suicide attempts also received inadequate treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Major depression is undertreated pharmacologically, regardless of history of suicide attempt. Some suicide attempts may be preventable if the problem of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression can be overcome by psychoeducation for health professionals and the public.

More than 50% of suicides occur in the context of an episode of major depression (1, 2), which raises the question of why the discovery of highly effective antidepressant medications has had little effect on suicide rates (3). One possible explanation is that potential suicide victims with major depression are not diagnosed or are undertreated (4– 8). Psychological autopsy studies (4, 7) have shown that between 9% and 33% of suicide completers with major depression were receiving antidepressants at the time of death and that fewer still received adequate doses of antidepressants. Studies in clinical populations (9–13) have documented underdiagnosis and undertreatment of major depression, regardless of suicidal behavior.

It is not clear whether the rate of diagnosis and treatment of major depression in suicidal patients differs from that in patients with major depression who are not at higher risk for suicide. Depressed patients with a history of suicide attempts have an elevated risk for suicidal behavior, including completed suicide, than depressed patients who have never attempted suicide (14, 15). Although two clinical studies (9, 11) found that subjects who have attempted suicide and those who had suicidal tendencies are undertreated for depression, our computer-assisted review of the literature revealed no reports comparing somatic treatment received by depressed patients with a history of suicide attempts with that received by depressed patients who never made suicide attempts. Thus, whether suicidal depressed patients who contact a physician are receiving treatment comparable to the treatment received by nonsuicidal depressed patients remains unknown. We conducted a study to determine whether depressed patients who attempted suicide receive less intensive antidepressant treatment, thereby explaining part of the reason for suicide attempts.

METHOD

Subjects

One hundred eighty inpatients admitted to two university hospitals (in New York City and Pittsburgh) who met DSM-III-R criteria for a major depressive episode after being interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (16) were enrolled in the study. All subjects provided written informed consent as approved by the institutional review boards of both hospitals.

All patients were given physical examinations and routine blood tests, including urine toxicology. Exclusion criteria included current substance or alcohol abuse, neurological illness, and active medical conditions. Patients with a history of substance or alcohol abuse more than 6 months preceding admission were included. All patients were assessed for the presence of a lifetime history of suicide attempts by using the Suicide History Form. This form is a semistructured instrument devised by our group that elicits information about lifetime suicide attempts, their method, lethality, precipitant, and surrounding circumstances. Our group has found this instrument to be reliable, yielding an interrater reliability coefficient of 0.97 (unpublished data). Depressive symptoms at the index hospitalization were assessed by using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17) and the Beck Depression Inventory (18).

Strength of Antidepressant Treatment

A history of pharmacological treatment for depression was obtained for the 3 months preceding the index hospitalization. Strength of antidepressant treatment was ascertained by using the Antidepressant Treatment History Form (19). A therapeutic dose was defined as a score of 3 or greater on a scale of 0 to 5 on this instrument, which scores the adequacy of antidepressant treatment trials for the major pharmacological antidepressant categories and ECT and has been shown to have good reliability and validity (19, 20). For all categories of antidepressants, the minimum duration of the treatment with a specific dose is 4 weeks. The minimum adequate daily dose for the tricyclics is at least 200 mg of imipramine hydrochloride or its equivalent; for SSRIs, the minimum daily dose is at least 20 mg of fluoxetine or its equivalent; for phenelzine, the minimum is at least 61 mg; for venlafaxine, the minimum is 225 mg; for bupropion, the minimum is 300 mg; and for ECT, the minimum is more than six unilateral or bilateral treatments. (See the work of Sackeim et al. [19] for details.)

Suicide Attempter Status

We assessed the medication treatment given to the patients in the 3 months preceding admission. We defined “remote attempters” as individuals who had a history of past suicide attempts, before the 3-month period of interest in this study. Treating clinicians would have regarded these patients as suicide attempters; therefore, patients who had made an attempt more than 90 days preceding admission were categorized as remote attempters (N=80) and could be considered a higher risk group. The nonattempter group included 91 patients: 83 of these patients had never made a suicide attempt, and eight had made a suicide attempt in the 7 days preceding the index hospitalization but had no previous lifetime history of suicide attempts. These eight patients were included in the nonattempter category because their recent suicide attempt would not have influenced their treatment in the 3 months preceding admission, but the fact that they had no previous history of suicide attempts would have an effect on their treatment during this time. Nine patients initially admitted to the protocol who had no remote history (more than 3 months earlier) of suicide attempts made a suicide attempt between 90 and 8 days preceding admission. Since we were interested in understanding the effect of a history of suicide attempts rather than a current attempt on antidepressant treatment, these patients were excluded from the analysis. Of note, only two of these patients received adequate antidepressant treatment.

Comparability of Subjects Across Sites

The patients in New York and Pittsburgh were comparable in all variables except for modest differences in age, total number of years of education, length of current episode, and number of lifetime major depressive episodes. The mean ages of the New York nonattempter and remote attempter groups were 8 and 6 years higher, respectively, than the mean ages of the Pittsburgh groups. As expected, attempters were younger than nonattempters in both cities. The New York nonattempter and remote attempter groups had means of 2 and 3 more years of education, respectively, than the Pittsburgh groups. Patients at both sites had mean educational levels of at least high school completion.

The New York nonattempters and remote attempters had means of about 0.58 and 0.36 more previous episodes, respectively, than the Pittsburgh groups. The differences in number of previous episodes of depression were not clinically significant. The median length of the current episode of New York patients was about 50% longer than that of the Pittsburgh patients. New York patients had been ill longer than Pittsburgh patients, reflecting different referral patterns to the inpatient unit.

Clinically and statistically, patients across the sites were comparable in sex distribution, marital status, age at onset of depression, subjective depression (according to the Beck inventory), absence of psychosis, and objective depression (according to the Hamilton depression scale).

Data Analysis

Quantitative variables were analyzed by using analysis of variance with remote attempter status, site (New York or Pittsburgh), and their interaction as independent variables. Two variables—length of current episode and number of episodes—had highly skewed distributions. They were analyzed on the log scale. Binary variables were analyzed by using logistic regression with the same independent variables.

RESULTS

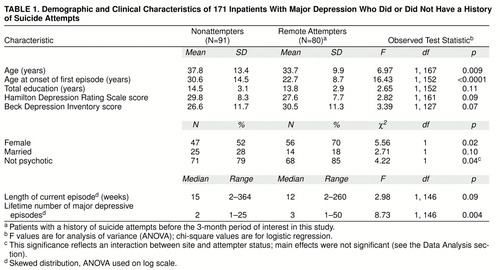

Remote attempters were more likely to be female and younger (table 1). They also were younger at the onset of the first episode of major depression and had more previous episodes of major depression (table 1). However, the depression was similar in severity both subjectively (Beck inventory) and objectively (Hamilton depression scale). A smaller percentage of the attempters were considered psychotic (table 1). Although patients with a history of substance abuse were somewhat more likely to be remote suicide attempters than those without (47 [53%] versus 33 [39%]), this finding did not reach statistical significance (p=0.07).

Only 26 (15%) of the 171 patients, both attempters and nonattempters, were taking any antidepressant medication on admission to the hospital. Only 35 (21%) of the patients (23 [18%] in Pittsburgh and 12 [33%] in New York) received adequate somatic antidepressant treatment at some point in the 3 months preceding admission. Critically, depressed patients with a history of remote suicide attempts were not more likely to receive adequate antidepressant treatment (10 [17%] in Pittsburgh and 6 [33%] in New York) than were depressed patients with no history of suicide attempts (13 [18%] in Pittsburgh and 6 [33%] in New York). This was true regardless of history of substance abuse or no abuse.

DISCUSSION

Our main finding is that a large majority of depressed patients with a history of suicide attempts, who are at higher risk for future suicide attempts and suicide, received inadequate treatment for depression. Similarly, a large majority of depressed patients who had never attempted suicide, who were at lower risk for suicide, received inadequate treatment. Therefore, it appears that both groups of depressed patients were inadequately treated to a comparable degree and that the higher-risk patients were not more poorly treated. In fact, because our study examined medication treatment as reported by the patients, it likely overestimated treatment adequacy by not accounting for treatment noncompliance.

These results are consistent with findings from psychological autopsy studies of completed suicides. One study of suicide victims (7) revealed that in the 3 months preceding suicide, about half of the patients received medical attention; among these treated patients, 73% of the women and 40% of the men received prescriptions. The suicide victims who received prescriptions obtained and filled 1.5 times more prescriptions than matched control subjects selected from a prescription monitoring system. However, only a small proportion of the suicide victims (13% of the women and 9% of the men) received antidepressants, often in subtherapeutic doses. Similarly, in the San Diego Suicide Study (6), about two-thirds of the suicide victims who consulted a physician in the 90 days preceding suicide were diagnosed as depressed, but less than half of the suicide victims who were seen by a physician received antidepressant medication. In Finland (4), two-thirds of subjects with a history of major depression at the time of suicide had received psychiatric treatment during their last year of life. However, even among these patients, antidepressant treatment was either absent or inadequate. Only 33% of the depressed suicide victims were receiving antidepressant medication at the time of death, despite the finding that 56% of the victims explicitly communicated their intent to either the person treating them or a family member. In another study comparing 64 inpatients who committed suicide with 64 inpatients who did not (5), patients who did not attempt suicide were more likely to be taking psychiatric medications (81% versus 49%). Postmortem studies of suicide victims (4–7) have found that 20% to 66% of suicides were among people who were taking antidepressants. The rates of any antidepressant treatment in suicide victims who consult a physician are certain to be greater than rates of adequate treatment, a concept that is consistent with our findings in remote attempters.

Our study group was comparable to those of previously reported studies in several important aspects. We found some important differences between patients with a remote history of suicide attempts and those with no history of attempts. Remote attempters had an earlier age at onset of first episode of major depression than nonattempters. Bulik et al. (21) and Roy (22) reported the same findings in patients with major depressive episodes. The remote attempters in our study group were more likely to be female. Although it has been reported that suicide attempters with unipolar depression in the community are twice as likely to be female (23), not all studies replicate this finding (for example, references 21 and 22). Why women are more vulnerable to suicide attempts is not known.

One reason why depressed patients at higher risk, such as those with past suicide attempts, did not receive more intensive antidepressant treatment than patients without a history of suicide attempts may lie in the absence of a noticeable clinical difference. The level of depression of remote attempters as measured subjectively (by the Beck inventory) or objectively (by the clinician using the Hamilton depression scale) did not differ from that of nonattempters in this series of patients. There was a trend for attempters to report more depression subjectively. That suicide attempts are unrelated to the objective severity of depression has been previously reported by us and others (24–26).

Many studies have documented the undertreatment of major depression in clinical populations as well (27). Keller et al. (11) reported that in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Study of the Psychobiology of Depression, only 12% of patients who were depressed according to Research Diagnostic Criteria received doses of more than 150 mg/day of imipramine hydrochloride or its equivalent for at least 4 weeks. Moreover, of the nonpsychotic patients who had made one or more suicide attempts during the index episode, 73% had been treated with psychotherapy and 60% received minor tranquilizers as their main treatment modalities. Their overall treatment did not differ from that of the nonpsychotic depressed group as a whole. In later work, Keller et al. (9) reported that after enrolling in the NIMH Collaborative Study and receiving a careful diagnostic evaluation, only 24% of patients treated as inpatients and 19% of patients treated as outpatients received what could be described as adequate antidepressant treatment trials. This study is of interest because a failure to make the correct diagnosis did not explain the low levels of somatotherapy.

Other studies also reported similar levels of undertreatment. Kocsis et al. (12) reported that only 8% of outpatients entering a study of the treatment of chronic depression had ever received adequate treatment with antidepressants. Goethe et al. (13), in a chart review study, reported that 18.4% of inpatients with nonbipolar major depression at a private psychiatric hospital received no somatic treatment for their depression. In a more recent study of chronic depression, Keller et al. (10) reported that only 26.8% of patients had received previous treatment of at least 4 consecutive weeks of 150 mg/day of imipramine or its equivalent. Mulsant et al. (28) found that across three centers, only two out of 53 patients with psychotic depression had received an adequate combination of antidepressant and neuroleptic medication before receiving ECT. Among 100 nonpsychotic patients with major depression, Prudic et al. (20) documented that 65% had received at least one adequate antidepressant trial before receiving ECT.

Our current study reveals the degree to which patients with major depression and a history of suicide attempts are undertreated with medication. Although a history of attempting suicide could be used by the clinician as a marker of propensity for future attempts, patients with such a history were not treated more intensely than those without. It remains unclear whether those patients at substantial risk for suicide in association with major depression because of their history of suicidal acts are either not being recognized as at risk or are not receiving adequate somatic treatment despite the clinician’s recognition of their heightened vulnerability.

This study also confirms the previously noted undertreatment of major depression in clinical populations. These patients were admitted to the current study after the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Although efficacious, safer, and, in some cases, easier to administer, their use does not seem to have improved intensity of treatment for inpatients. In fact, even though our New York patients, who entered the study between 1995 and 1997, had higher Antidepressant Treatment History Form scores than the Pittsburgh patients, who entered between 1990 and 1994, this was not attributable to the greater use of SSRIs.

The major limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. The information about pharmacotherapy was from the patient’s report and may contain omissions or other mistakes. In addition, because medication compliance was not assessed, our estimate of treatment intensity is probably inflated. However, the number of subjects and the robust nature of the finding makes the conclusion compelling that major depression is undertreated pharmacologically regardless of the presence of a history of suicide attempt. These findings in patients with major depression are consistent with the low rate of antidepressant pharmacological treatment of major depression reported in psychological autopsy studies of suicide victims. Remarkably, the pattern of undertreatment persists despite the finding that patients with a past history of suicide attempts are at higher risk for completed suicide in the context of major depression (14, 15)

One possible solution to the problem of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression is psychoeducation for health professionals. The Gotland study (29) provides evidence that educational programs for general practitioners can increase the number of prescriptions written for antidepressants and decrease suicide rates. However, the educational effect is not a lasting one (30). Educational efforts need to be repeated at regular intervals, and their impact needs to be studied. Given the findings about prescription practices at the university settings in the NIMH Collaborative Study of the Psychobiology of Depression (9) and in primary care settings (29), educational programs need to be geared toward primary care physicians as well as specialists in all branches of medicine, not just psychiatry. Such efforts are needed to take advantage of the availability of highly effective medication treatment for major depression and may be an essential step in reducing rates of suicide.

Received Jan. 5, 1998; revisions received May 7 and Aug. 24, 1998; accepted Sept. 17, 1998. From the Mental Health Clinical Research Center for the Study of Suicidal Behavior, Departments of Neuroscience and Biological Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute. Address reprint requests to Dr. Oquendo, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 722 West 168 St., New York, NY 10032; [email protected]. columbia.edu (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-35636, MH-46745, MH-40695, and MH-48514 Clinical ratings were completed by members of the Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Core of the Mental Health Clinical Research Center.

|

1. Barraclough B, Bunch J, Nelson B, Sainsbury P: One hundred cases of suicide: clinical aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125:355–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Dorpat TL, Ripley HS: A study of suicide in the Seattle area. Compr Psychiatry 1960; 1:349–359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. La Vecchia C, Lucchini F, Levi F: Worldwide trends in suicide mortality, 1955–1989. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:53–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Isomets� ET, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Heikkinen ME, Kuoppasalmi KI, L�nnqvist JK: Suicide in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:530–536Link, Google Scholar

5. Modestin J, Schwarzenbach F: Effect of psychopharmacotherapy on suicide risk in discharged psychiatric inpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:173–175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL: Antidepressants, depression and suicide: an analysis of the San Diego study. J Affect Disord 1994; 32:277–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Isacsson G, Bo�thius G, Bergman U: Low level of antidepressant prescription for people who later commit suicide: 15 years of experience from a population-based drug database in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:444–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rihmer Z, Barsi J, Veg K, Katona CLE: Suicide rates in Hungary correlate negatively with reported rates of depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 20:87–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Coryell W, Fawcett J, Rice JP, Hirschfeld RM: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:458–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Keller MB, Harrison W, Fawcett JA, Gelenberg A, Hirschfeld RMA, Klein D, Kocsis JH, McCullough JP, Rush AJ, Schatzberg A, Thase ME: Mood disorders: treatment of chronic depression with sertraline or imipramine: preliminary blinded response rates and high rates of undertreatment in the community. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:205–212Medline, Google Scholar

11. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Fawcett JA, Coryell W, Endicott J: Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA 1982; 248:1848–1855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kocsis JH, Frances AJ, Voss C, Mann JJ, Mason BJ, Sweeney JA: Imipramine treatment for chronic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:253–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Goethe JW, Szarek BL, Cook WL: A comparison of adequately vs inadequately treated depressed patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1988; 176:465–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Nordstr�m P, �sberg M, Aberg-Wistedt A, Nordin C: Attempted suicide predicts suicide risk in mood disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92:345–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fawcett J, Scheftner W, Clark D, Hedeker D, Gibbons R, Coryell W: Clinical predictors of suicide in patients with major affective disorders: a controlled prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:35–40Link, Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Version 1.0 (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

17. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Decina P, Kerr B, Malitz S: The impact of medication resistance and continuation pharmacotherapy on relapse following response to electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10:96–104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, Malone KM, Pettinati HM, Stevens S, Greenberg R, Rifas SL, Sackeim HA: Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:985–992Link, Google Scholar

21. Bulik CM, Carpenter LL, Kupfer DJ, Frank E: Features associated with suicide attempts in recurrent major depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 18:29–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Roy A: Features associated with suicide attempts in depression: a partial replication. J Affect Disord 1993; 27:35–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Chen Y-W, Dilsaver SC: Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:896–899Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Mann JJ: Major depression and the risk of attempted suicide. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:173–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. van Praag HM, Plutchik R: Depression type and depression severity in relation to risk of violent suicide attempt. Psychiatry Res 1984; 12:333–338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Mezzich J, Cornelius MD, Fabrega HF Jr, Ehler JG, Ulrich RF, Thase ME, Mann JJ: Disproportionate suicidality in patients with comorbid major depression and alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:358–364Link, Google Scholar

27. Hirschfeld RMA, Keller M, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Guthrie D, Marek RG, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Philips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Mulsant BH, Haskett RF, Prudic J, Thase ME, Malone KM, Mann JJ, Pettinati HM, Sackeim HA: Low use of neuroleptic drugs in the treatment of psychotic major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:559–561Link, Google Scholar

29. Rutz W, Von Knorring L, W�linder J: Frequency of suicide on Gotland after systematic postgraduate education of general practitioners. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 80:151–154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Rihmer Z, Rutz W, Pihlgren H: Depression and suicide on Gotland—an intensive study of all suicides before and after a depression-training programme for general practitioners. J Affect Disord 1995; 35:147–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar