Borderline Personality Disorder in Clinical Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Most studies of borderline personality disorder have drawn patients from among hospital inpatients or outpatients. The aims of this study were to examine the nature of borderline personality disorder patients in everyday clinical practice and to use data from a sample of borderline personality disorder patients seen in the community to refine the borderline construct. METHOD: A random national sample of 117 experienced psychiatrists and psychologists from the membership registers of the American Psychiatric Association and American Psychological Association provided data on a randomly selected patient with borderline personality disorder (N=90) or dysthymic disorder (N=27) from their practice. The clinicians provided data on axis I comorbidity, axis II comorbidity, and adaptive functioning, as well as a personality description of the patient using the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200 (SWAP-200) Q-sort, an instrument designed for assessment and taxonomic purposes. Analyses compared borderline personality disorder and dysthymic disorder groups on variables of interest and aggregated SWAP-200 items across all borderline personality disorder patients to create a composite portrait of borderline personality disorder as seen in the community. RESULTS: The borderline personality disorder sample strongly resembled previously studied borderline personality disorder samples with regard to comorbidity and adaptive functioning. However, the SWAP-200 painted a portrait of borderline personality disorder patients as having more distress and emotion dysregulation, compared to the DSM-IV description. CONCLUSIONS: Borderline personality disorder patients in research samples are highly similar to those seen in a cross-section of clinical practice. However, several studies have now replicated a portrait of borderline personality disorder symptoms that places greater weight than the DSM-IV description on the intense psychological pain of these patients and suggests candidate diagnostic criteria for DSM-V.

Since the first research using a standardized interview for borderline personality disorder patients two decades ago (1), an immense body of research has emerged on the nature and etiology of borderline personality disorder. Most studies have drawn subjects from groups of outpatients or inpatients, usually associated with academic training departments (e.g., references 2–19). To what extent these patients, who are likely to have symptoms on the more disturbed end of the borderline spectrum, resemble the range of borderline personality disorder patients seen in everyday practice is largely unknown.

The aims of the current study were twofold. The first was to describe the nature of borderline pathology seen in clinical practice. We compared data from prior studies with data from a random national sample of borderline personality disorder patients treated in the community on three sets of criteria: axis I comorbidity, axis II comorbidity, and adaptive functioning. Gunderson’s review (20) indicated that the axis I disorders most frequently found in borderline personality disorder patient samples are dysthymic disorder, major depression, substance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders and that at least one-half of borderline personality disorder patients have major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or both. Although borderline personality disorder has been found to have high rates of comorbidity with virtually all axis II disorders, the highest diagnostic overlap appears to be with histrionic and avoidant personality disorders (20, 21). With regard to adaptive functioning, research findings have associated borderline personality disorder with self-injurious behavior such as skin cutting and burning and with psychiatric hospitalizations, suicidality, difficulty maintaining relationships, and difficulty maintaining appropriate employment. We thus expected to see similar patterns of findings in a community clinical sample if the descriptions of borderline personality disorder generated from hospital inpatients and outpatients generalize.

The second aim was to describe the personality characteristics of borderline personality disorder patients by using a large, relatively comprehensive item set and to refine the borderline construct empirically by using a broad sample of borderline personality disorder patients seen in the community. In a prior study (22, 23), a large random national sample of experienced clinicians described a personality disorder patient by using the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200 (SWAP-200) (22), a clinician-report personality pathology Q-sort instrument that includes items reflecting the roughly 80 DSM-IV criteria for all current axis II diagnoses as well as 120 additional items that provide candidate criteria for refining current diagnoses (i.e., potential alternative diagnostic criteria). Of 530 clinician-participants, 43 described a patient with borderline personality disorder. Among the items most characteristic of the borderline personality disorder patients in this sample were several that mirrored DSM-IV criteria. Other items, however, appeared to be more characteristic of the average borderline personality disorder patient than several of the DSM-IV criteria, notably items describing intense and poorly modulated affect and profound dysphoric affect. The data suggested that intense dysphoric affect is a core, rather than co-occurring, feature of borderline personality disorder. Similar findings emerged in a prior study that used the SWAP-167, the progenitor to the SWAP-200 (24). The results of these studies were in keeping with Gunderson’s finding that chronic major depression and chronic feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, worthlessness, guilt, loneliness, and emptiness appear to be central to the disorder (20).

In the present study, we asked a random national sample of experienced clinicians to provide data on phenomenology, comorbidity, and adaptive functioning in a randomly selected patient with DSM-IV-diagnosed borderline personality disorder, and we used data from the SWAP-200 Q-sort to develop an empirical portrait of the personality functioning of the average patient with borderline personality disorder. Given that the instrument includes items assessing all current axis II criteria, if personality descriptors that were not among the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria appeared to be more diagnostic than the current criteria in a sample specifically selected for meeting those criteria, and if these descriptors replicated those found to be more descriptive of borderline personality disorder patients in prior research, these findings would suggest the need for refining the borderline construct to mirror more closely the nature of patients seen in the community.

Method

The present investigation relied on practice network methods to address taxonomic and other basic science questions. Elsewhere we addressed in detail the rationale for this clinician-report method, including its advantages and limitations (see references 22, 25–30). In brief, clinicians are experienced observers who observe patients longitudinally and in depth. Although unstructured clinical judgments have been shown to have poor reliability and validity, a host of recent studies suggested that clinicians can provide highly reliable and valid data when they quantify their judgments using psychometric instruments and that their data predict data from independent interviews (27, 31–33). In multiple studies, clinicians’ theoretical orientation has predicted little variance when clinicians were asked to describe a specific patient rather than their beliefs about or theories of psychopathology (see, e.g., references 24, 34).

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 117 clinicians who constituted a random national sample of experienced psychiatrists and psychologists from the membership registers of the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association. Initial letters to clinicians described the study, presented them with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder and dysthymic disorder (which was selected as a comparison condition), and asked them to complete a postcard indicating whether they had at least one borderline personality disorder or dysthymic disorder patient in their practice who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Based on their postcard responses, we assigned the clinicians to describe either a borderline personality disorder patient (N=90) or a dysthymic disorder patient (N=27), again presenting them with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder and/or dysthymic disorder to ensure close attention to the diagnostic criteria. To ensure random selection of patients, we asked the clinicians who reported having more than one appropriate patient to consult their calendars and select the patient they saw most recently who met the study criteria. For the dysthymic disorder group, we asked clinicians to describe a current patient who met the DSM-IV criteria for dysthymic disorder and who had no diagnosable DSM-IV personality disorder and no more than three DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder. For patients in both groups, we asked clinicians to select a female patient (to avoid the confounding factor of gender and to maximize power, because 75%–80% of patients who receive a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder are female [20, DSM-IV]) between ages 18 and 55 years (to avoid the confounding factors associated with adolescent and late-life personality disorder diagnosis) whom they had seen for a minimum of eight sessions and a maximum of 2 years (to guarantee that they knew the patient well while minimizing the likelihood of substantial personality change in treatment) and who did not have a psychotic disorder. We asked clinicians to select a current psychotherapy patient to maximize the likelihood of their being able to provide detailed personality assessments. (We selected a comparison group of patients with dysthymic disorder because patients with depression have been the most common comparison group in studies of personality disorders, and patients with dysthymic disorder have enduring, moderate depression that is also common in patients with borderline personality disorder.) To maximize participation, we gave clinicians the option to participate by pen and paper or on our interactive web site (http://www. psychsystems.net). Consistent with the literature on computerized versus paper administration of questionnaires (35), we found no systematic differences between responses with the two methods.

Before analyzing the data, we excluded data on patients who were extreme outliers in age or length in treatment beyond the parameters we requested, data on patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for the borderline personality disorder or dysthymic disorder groups, and data suggesting extreme carelessness in responding (e.g., multiple pages not completed). To maximize power, however, we retained patients who exceeded within reasonable bounds the maximum limit for age (two patients whose ages were in the range of 55–61 years) and time in treatment (six patients whose time in treatment ranged from 25 to 48 months). Further, because several dysthymic disorder patients were one criterion short of the diagnostic criteria for the disorder or met the criteria for multiple personality disorders, we were faced with decisions about the “purity” of the dysthymic disorder sample. We ultimately chose to retain patients who had chronic depression if they were within one criterion of the dysthymic disorder diagnosis and to retain dysthymic disorder patients who met the DSM-IV criteria for a non-borderline-personality-disorder diagnosis (mostly avoidant and schizoid personality disorders) to maximize the number of subjects and the generalizability of the sample. The decision to include non-borderline-personality-disorder patients actually rendered findings more conservative and increased external validity, given the high rates of comorbidity (60%) for dysthymic disorder and personality disorders in prior research (36, 37). (In fact, we reran all analyses without the eight patients who did not meet the criteria, and significance values improved in three cases and decreased from 0.01 to 0.05 in one. However, to preserve consistency with other reports of data from this sample, we chose to avoid excluding these subjects for some analyses but not for others.)

Measures

Clinicians completed the following measures, presented in the following order. (We included other instruments for other studies but do not describe them here.)

Clinical Data Form

The Clinical Data Form was used to assess a range of variables relevant to demographics, diagnosis, adaptive functioning, developmental history, and family history of psychopathology. This measure was developed over several years and used in a number of studies (see reference 38). The sections of the Clinical Data Form that were relevant to this study ask clinicians to provide basic demographic data on themselves and the patient, as well as information pertaining to the patient’s diagnosis and adaptive functioning. Prior research found such ratings to correlate strongly with ratings made by independent interviewers (28, 33, 39).

SWAP-200

The SWAP-200 is a 200-item Q-sort designed to assess personality and personality pathology (e.g., references 22, 24, 27, 38). (A Q-sort is a set of statements printed on separate index cards, in this case, statements about personality and personality dysfunction.) An experienced clinical observer sorts the cards into eight piles, thereby assigning each of the 200 descriptive items a numerical score ranging from 0 (for items least descriptive of the patient) to 7 (items most descriptive of the patient). Items for the SWAP-200 were derived from a number of sources, including DSM-III-R and DSM-IV axis II criteria, clinical literature on personality disorders, research on personality disorders, research on normal personality traits and psychological health, pilot interviews, and the feedback of more than 1,000 clinicians. Development of the item set was an iterative process that followed standard psychometric methods, such as eliminating redundant items, items with minimal variance, and so forth. The Q-sort items provide a standardized clinical language that allows for clinicians’ assessments to be quantified, compared with those of other clinicians, and analyzed statistically.

Research thus far has supported the validity and reliability of the SWAP-200 in predicting numerous external criteria, such as suicide attempts and history of psychiatric hospitalizations, adaptive functioning assessed by measures such as the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) from the DSM-IV, diagnoses based on interviews, and developmental and family history variables (e.g., references 25, 27, 34). The SWAP-200 has been used for taxonomic purposes in multiple studies (e.g., for empirically deriving personality diagnoses from large samples of adult and adolescent patients [references 27, 40]).

Axis I checklist

Clinicians completed a present/absent checklist of the most common axis I DSM-IV diagnoses in borderline personality disorder reported in the literature, including major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, anorexia nervosa (restricting type), anorexia nervosa (binge-eating/purging type), bulimia nervosa (purging type), bulimia nervosa (nonpurging type), alcohol abuse/dependence, prescription drug abuse/dependence, and illicit drug abuse/dependence. For a subset of disorders in which we were particularly interested (dissociative disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and dysthymic disorder), we asked clinicians to make present/absent distinctions on each DSM criterion for each disorder, which allowed us to apply DSM-IV algorithms to identify patients who met the diagnostic criteria.

Axis II checklist

Clinicians completed a checklist containing the criteria for the DSM-IV personality disorders, randomly ordered, so that we could assess axis II pathology both dimensionally (number of symptoms endorsed) and categorically (applying DSM-IV cutoffs), again without relying on clinicians’ global diagnoses. Similar methods have been employed by other researchers, such as Blais and Norman (41).

Data Analysis

The aims of the study were 1) to examine the nature of borderline personality disorder patients in everyday clinical practice and their resemblance to borderline personality disorder patients seen in research studies and 2) to see if we could identify candidate diagnostic criteria for a revision of DSM-IV. Thus, after conducting diagnostic validity checks, we examined their similarity to borderline personality disorder patients prototypically described in research accounts in terms of axis I and axis II comorbidity and adaptive functioning. We hypothesized that the borderline personality disorder group, compared to the dysthymic disorder group, would demonstrate lower levels of various indices of adaptive functioning in chi-square analyses for categorical variables and t tests for dimensional variables. We report Pearson’s r as an effect size estimate throughout. (For interpretations of r as a measure of effect size, see references 42, 43.) To create a composite personality portrait of borderline personality disorder in everyday practice and to see if we could identify candidate criteria for the disorder that might be more identifying than the DSM-IV criteria, we aggregated SWAP-200 item scores across all borderline personality disorder patients.

Results

Demographics

Of the 117 clinician-participants, 19% (N=22) were psychiatrists and 81% (N=95) were psychologists (the latter responded at a much higher rate to the initial solicitation); 42% (N=49) were female. The majority worked at least part time in private practice (88%, N=103), although many worked in other settings as well, with 18% (N=21) working in a clinic; 26% (N=30) in outpatient, inpatient, or partial hospital settings; 8% (N=9) in a forensic setting; and 16% (N=19) in other settings. Clinicians were diverse in theoretical orientation, with 21% (N=24) describing their psychotherapeutic orientation as cognitive behavioral or behavioral, 44% (N=52) as psychodynamic or psychoanalytic, 32% (N=37) as eclectic, and 3% (N=4) as other.

Patients were an average age of 38 years (SD=10.14). The sample was predominantly Caucasian (88%, N=103); about 5% (N=6) were Hispanic, and the remainder were African American, Asian, or another ethnicity. Patients were primarily working class (33%, N=39) and middle class (47%, N=55), with educational attainment ranging from high school degree (15%, N=18) to having some graduate education (26%, N=30). Patients had been in treatment for an average of 12 months (SD=7.8), so the clinicians knew them well.

Validity Check

As a validity check, we conducted two t tests to compare borderline personality disorder and dysthymic disorder patients on two measures of borderline personality disorder. Using the clinicians’ 7-point ratings of the extent to which patients matched the borderline personality disorder construct, we found that clinicians rated borderline personality disorder patients significantly higher than dysthymic disorder patients (t=27.72, df=29.15, p<0.001, r=0.97). The same pattern emerged when we instead used SWAP-200 borderline personality disorder scale scores as the criterion variable (t=12.26, df=115, p<0.001, r=0.75) (17).

Borderline Personality Disorder as Seen in Everyday Practice

Comorbidity

Table 1 reports the frequency of comorbid axis I conditions in the two groups. The borderline personality disorder group distinguished itself both by the sheer number of comorbid diagnoses on average and by the specific diagnoses that have commonly been reported in reviews of studies of borderline personality disorder patients (20, 21).

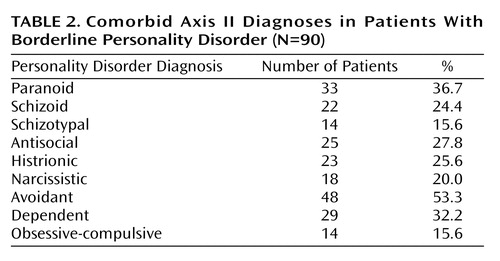

We assessed axis II comorbidity by applying DSM-IV algorithms to the axis II symptom checklist data. As Table 2 shows, comorbidity was substantial, with the pattern once again strongly resembling that reported in prior studies (20, 21). (We do not report axis II comorbidity data for the dysthymic disorder patients because we requested that the clinicians provide data for dysthymia disorder patients without personality disorder diagnoses.)

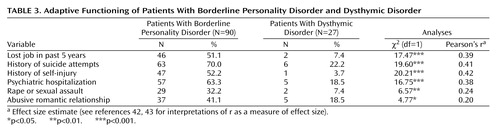

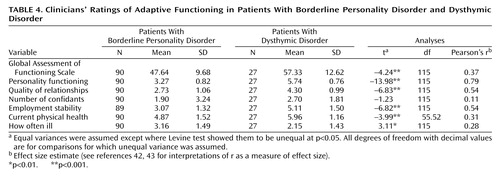

Adaptive functioning

As Table 3 and Table 4 show, borderline personality disorder patients functioned significantly more poorly than dysthymic disorder patients on multiple indices of adaptive functioning. For example, on a 7-point rating of chronic level of personality functioning based loosely on Kernberg’s model of levels of functioning (44) (using four anchors: “psychotic,” “personality disorder,” “substantial problems,” and “high-functioning”), clinicians rated the dysthymic disorder patients more than 2 points (and three standard deviations) higher than the borderline personality disorder patients. The one exception was the number of confidants, a measure of social support, which makes sense in light of the association of borderline personality disorder with the personality trait of extroversion (45).

Most (70%, N=63) of the borderline personality disorder patients had attempted suicide. Attempters on average had made 3.89 attempts (SD=6.72), with the severity of the most dangerous attempt rated on average as “moderate, requiring medical attention.” Most (63%, N=57) of the borderline personality disorder patients had at least one psychiatric hospital admission, and those who had a history of hospitalization had an average of 3.67 admissions (SD=3.92). More than one-half of the borderline personality disorder patients (52%, N=47) had self-injured. Of the 47 borderline personality disorder patients who self-injured, 81% (N=38) cut, 23% (N=11) burned, and 13% (N=6) severely scratched or tore their skin; an additional 26% (N=12) had repeated accidents.

Patients with borderline personality disorder showed generally poor relational functioning across several measures. Of particular interest, 41% (N=37) had been in abusive relationships in adulthood, with the majority in the role of victim (60%, N=22), a substantial minority in the roles of both victim and perpetrator (38%, N=14), and only one exclusively in the role of perpetrator. Nearly one-third (32%, N=29) had been the victim of rape or sexual assault in adulthood (see reference 46), and, for borderline personality disorder patients who reported any such incident, rape or sexual assault occurred on average 2.75 times (SD=3.66).

Identifying Candidate Diagnostic Criteria

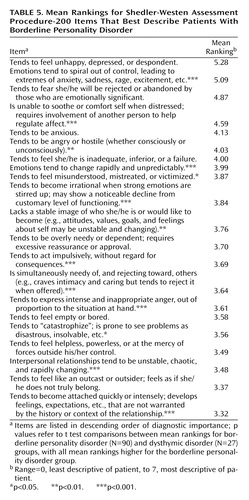

To construct a composite personality portrait of borderline personality disorder in clinical practice, we aggregated scores for each of the 200 items of the SWAP-200 across all 90 borderline personality disorder patients by taking the mean across subjects and then arraying the items in descending order of magnitude (i.e., beginning with the items most characteristic of the borderline personality disorder patients). Table 5 lists the items with the highest average rankings. (Items ranked significantly higher for borderline personality disorder patients than for dysthymic disorder patients are starred in Table 5.)

Most DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder were represented among the SWAP-200 items with the highest average rankings. However, several SWAP-200 items with the highest average rankings were not reflected in the DSM-IV criteria. Table 6 presents the non-DSM-IV items that were rank-ordered among the top 20 items, all of which also ranked within the 20 most descriptive items in the largest prior sample to date in which this method was used (23), suggesting that the findings are robust and not attributable to particular characteristics of the present sample. In general, these items captured negative affect, emotion dysregulation, and poor self-esteem or self-loathing. Perhaps most striking, the two items most descriptive of borderline personality disorder patients in both samples were “Tends to feel unhappy, depressed, or despondent” and “Emotions tend to spiral out of control.”

Discussion

Primary Findings

Virtually all research on patients with borderline personality disorder has studied samples from hospital inpatient units or outpatient clinics. This study compared borderline personality disorder patients with dysthymic disorder patients treated in the community to see whether the phenomena observed in prior samples characterize borderline personality disorder patients as treated in the community or whether samples of borderline personality disorder patients from hospitals and university clinics provide an overly pathological portrait of the disorder. The results point to two primary conclusions.

First, the data from prior studies, which could be expected to oversample the more severe end of the borderline spectrum, nevertheless generalized well to the patients seen by randomly selected clinicians across a wide variety of settings. In terms of axis I comorbidity, the borderline personality disorder sample in our study was very similar to other borderline personality disorder samples reviewed by Gunderson (20), with a profile of high emotional distress (in the form of mood and anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder) and problematic ways of managing it (e.g., dissociative disorders, substance abuse, eating disorders). The findings were also consistent with Gunderson’s review of research on axis II comorbidity in borderline personality disorder (20, 21, 47), in which 90%–97% of borderline personality disorder patients were found to meet the criteria for other DSM personality disorder diagnoses. In our sample, the axis II checklist identified substantial rates of comorbidity for every axis II personality disorder, with particularly high frequencies of avoidant, paranoid, and dependent personality disorders. The slightly higher rates of avoidant and dependent personality disorder diagnoses in this sample may reflect the possibility that the community treatment-seeking sample is more withdrawn and dysphoric than the more acute hospital or university clinic samples or may reflect changes in borderline personality disorder criteria between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV.

With respect to adaptive functioning, like the borderline personality disorder patients studied in prior investigations, the borderline personality disorder patients treated in everyday practice showed substantial deficits. More than two-thirds had attempted suicide, more than one-half had self-injured (mostly by cutting), and almost two-thirds had been hospitalized at least once. Clinicians reported that borderline personality disorder patients had lower quality of relationships and unstable work histories, with more than one-half having lost a job in the past 5 years because of interpersonal problems.

Of particular interest are findings on physical health and abusive experiences in adulthood, as these areas of functioning have not received as much empirical attention as other aspects of adaptation. Borderline personality disorder patients appeared to have frequent or chronic minor illnesses, leading to missed appointments, days off from work, visits to the doctor, or subjective distress. Forty percent of the borderline personality disorder patients in this sample also had been in abusive relationships in adulthood, with virtually all being victimized (whether or not they also at times perpetrated violence). Nearly one-third of the borderline personality disorder patients had been the victim of rape or other serious sexual assault in adulthood, with such experiences typically occurring multiple times. A recent study by Zanarini et al. (46) produced similar results.

Second, the data provide a portrait of the average patient with DSM-IV-diagnosed borderline personality disorder seen in clinical practice, and this portrait converges with the DSM-IV description in multiple respects but diverges in others. Of the 200 items in the SWAP-200, several designed to reflect DSM-IV diagnostic criteria appeared empirically among the 20 items that were most descriptive of patients who receive a borderline personality disorder diagnosis. These items describe rejection/abandonment fears, unstable relationships, unstable identity, impulsivity, labile emotions, feelings of emptiness or boredom, and intense anger. On the other hand, several DSM-IV criteria were not ranked highly among the SWAP-200 descriptors of actual borderline personality disorder patients, and other items not included in DSM-IV received higher rankings on average than many current criteria.

Among the DSM-IV criteria that did not receive high average rankings were items describing the tendency to see people as “all good” or “all bad” (either because empirically these concepts are not as central to the diagnosis or because splitting them into two items may have decreased the ranking of both) and items describing specific forms of impulsivity, such as alcohol abuse and promiscuous sex. The hybrid criterion added to DSM-IV regarding transient psychotic symptoms and dissociative episodes did not rank highly. However, a related item that ranked tenth in the borderline personality disorder sample better appears to capture an aspect of the construct originally intended by Gunderson (21) and should be considered as a replacement criterion for DSM-V: “tends to become irrational when strong emotions are stirred up; may show a noticeable decline from customary level of functioning.” Although clinicians reported significant self-injury and suicidality (on the Clinical Data Form), SWAP-200 items for these phenomena did not rank as highly as other items. These differences may reflect a sampling difference between prior studies and the present investigation or may reflect the differential salience of particular high-risk behaviors when reported to an interviewer on a single occasion, typically when the patient is most symptomatic and presents at a hospital or clinic for treatment, versus when the behavior is contextualized within a longitudinal portrait of the patient over time.

Several other SWAP-200 items emerged as more descriptive than some of the current borderline personality disorder criteria, despite the fact that we used DSM-IV criteria to define the patient sample. Perhaps most important was a set of items reflecting chronic (rather than transient) aspects of emotional experience, namely the tendency “to feel unhappy, depressed, despondent” (the item with the highest ranking of all the items in the SWAP-200 composite borderline personality disorder profile) and to feel anxious. These data suggest that DSM-IV may understate the pain and dysphoria borderline personality disorder patients feel. They also support the view that negative affect is a central trait in borderline personality disorder as currently defined (48, 49).

Another set of items that may not receive adequate representation among the criteria for borderline personality disorder in DSM-IV describes the related trait of emotion dysregulation (on the difference between negative affect and emotion dysregulation, see references 28, 34, 40). These items describe a person whose emotions tend to spiral out of control; who can become irrational when strong emotions are stirred; who tends to “catastrophize,” seeing problems as disastrous and insolvable; and who has difficulty self-soothing and hence may become overly dependent on others to help regulate emotion. These descriptions of emotion dysregulation appear clinically richer and more specific than the DSM-IV description of “affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood.” All of these items distinguished borderline personality disorder patients from dysthymic disorder patients, who share the trait of negative affect, and occurred at a similarly high rate in previous efforts to develop an empirical prototype of borderline personality disorder (22).

Limitations and Potential Objections

The data from this study, like the data from a number of studies from our laboratory (e.g., references 22, 25, 27, 29), point to the potential utility of practice research network methods in research on personality disorders. The convergence of multiple informants would clearly be ideal (although most studies of psychopathology rely on a single observer—the patient—by means of either self-report or structured interviews); however, data from experienced clinical observers who interact with the patient over time and hence can provide a longitudinal portrait provide a complementary standpoint to that typically seen in psychiatric research.

Another set of limitations concerns the makeup of the current sample. Psychologists were disproportionately represented in the sample, relative to psychiatrists (80% and 20%, respectively), and the overall response rate was relatively low, compared to our previous studies. Although we cannot be sure that some unknown bias was not introduced by clinicians’ decisions to participate or not participate, the data provided by psychologists and by psychiatrists did not show any pattern of differences in this or any of our prior studies using this method, despite substantially different response rates, and our findings converged with those of research from medical centers that used completely different sampling methods. The similarities in these findings suggest that such biases are not likely substantial. Limiting the study to patients in psychotherapy also introduced the possibility that we were oversampling higher-functioning borderline personality disorder patients. However, the data suggested otherwise: The majority of the borderline personality disorder patients in the study reported histories of psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, and self-injurious behavior, and their average GAF score (mean=47.64, SD=9.68) indicated serious impairment. Finally, male and non-Caucasian borderline personality disorder patients are understudied groups, and broader sampling, including oversampling to maximize representativeness of the population, would strengthen future investigations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Jan. 13, 2003; revision received Feb. 17, 2004; accepted May 19, 2004. From Cambridge Hospital/Harvard Medical School; and the Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Zittel Conklin, The Cambridge Hospital, Macht Building, 1493 Cambridge St., Cambridge, MA 02139; [email protected] (e-mail); or Dr. Westen, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University, 532 North Kilgo Circle, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected] (e-mail). Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIMH grants MH-62377 and MH-62378 to Dr. Westen and by a grant from the Fund for Psychoanalytic Research of the American Psychoanalytic Association to Dr. Zittel Conklin. Presented in part at the 2nd Annual Meeting of the National Institute of Mental Health and Borderline Personality Disorder Research Foundation, Minneapolis, May 30–June 1, 2002. The authors thank the 117 clinicians who donated up to 4 hours of their time to participate in the study.

1. Gunderson JG, Kolb JE, Austin V: The Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:896–903Link, Google Scholar

2. Clarkin JF, Hull JW, Hurt SW: Factor structure of borderline personality disorder criteria. J Personal Disord 1993; 7:137–143Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Golomb A, Ludolph P, Westen D, Block MJ, Maurer P, Wiss FC: Maternal empathy, family chaos, and the etiology of borderline personality disorder. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1994; 42:525–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McGlashan TH: The Chestnut Lodge follow-up study, III: long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:20–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. McGlashan TH: The longitudinal profile of borderline personality disorder: contributions from the Chestnut Lodge follow-up study, in Handbook of Borderline Disorders. Edited by Silver D, Rosenbluth M. Madison, Conn, International Universities Press, 1992, pp 55–83Google Scholar

6. Morey LC, Zanarini MC: Borderline personality: traits and disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:733–737Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nigg JT, Lohr NE, Westen D, Gold LJ, Silk KR: Malevolent object representations in borderline personality disorder and major depression. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:61–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, Hill EM: Childhood sexual and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1008–1013Link, Google Scholar

9. Sabo AN, Gunderson JG, Najavits LM, Chauncey D, Kisiel C: Changes in self-destructiveness of borderline patients in psychotherapy: a prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995; 183:370–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Shachnow J, Clarkin J, DiPalma CS, Thurston F, Hull J, Shearin E: Biparental psychopathology and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry 1997; 60:171–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Silk K, Nigg J, Westen D, Lohr N: Severity of childhood sexual abuse, borderline symptoms, and familial environment, in The Role of Sexual Abuse in the Etiology of Borderline Personality Disorder. Edited by Zanarini M. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997, pp 131–163Google Scholar

12. Silk KR, Lee S, Hill EM, Lohr NE: Borderline personality disorder symptoms and severity of sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1059–1064Link, Google Scholar

13. Stone MH: Long-term outcome in personality disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:299–313Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Stone MH, Hurt SW, Stone DK: The PI 500: long-term follow-up of borderline inpatients meeting DSM-III criteria, I: global outcome. J Personal Disord 1987; 1:291–298Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Westen D, Lohr N, Silk KR, Gold L, Kerber K: Object relations and social cognition in borderlines, major depressives, and normals: a Thematic Apperception Test analysis. Psychol Assess 1990; 2:355–364Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Westen D, Ludolph P, Block MJ, Wixom J, Wiss FC: Developmental history and object relations in psychiatrically disturbed adolescent girls. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1061–1068Link, Google Scholar

17. Westen D, Ludolph P, Misle B, Ruffins S, Block J: Physical and sexual abuse in adolescent girls with borderline personality disorder. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1990; 60:55–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Young DW, Gunderson JG: Family images of borderline adolescents. Psychiatry 1995; 58:164–172Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Khera GS, Bleichmar J: Treatment histories of borderline inpatients. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:144–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gunderson JG: Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001Google Scholar

21. Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Kisiel C: Borderline personality disorder, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 141–157Google Scholar

22. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, part II: toward an empirically based and clinically useful classification of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:273–285Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Shedler J, Westen D: Refining personality disorder diagnosis: integrating science and practice. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1350–1365Link, Google Scholar

24. Shedler J, Westen D: Refining the measurement of axis II: a Q-sort procedure for assessing personality pathology. Assessment 1998; 5:333–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Westen D, Harnden-Fischer J: Personality profiles in eating disorders: rethinking the distinction between axis I and axis II. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:547–562Link, Google Scholar

26. Morey LC: Personality disorders in DSM-III and DSM-III-R: convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:573–577Link, Google Scholar

27. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, part I: developing a clinically and empirically valid assessment method. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:258–272Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Westen D, Muderrisoglu S, Fowler C, Shedler J, Koren D: Affect regulation and affective experience: individual differences, group differences, and measurement using a Q-sort procedure. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:429–439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Wilkinson-Ryan T, Westen D: Identity disturbance in borderline personality disorder: an empirical investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:528–541Link, Google Scholar

30. Westen D, Weinberger J: When clinical description becomes statistical prediction. Am Psychol 2004; 59:595–613Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Dutra L, Campbell L, Westen D: Quantifying clinical judgment in the assessment of adolescent psychopathology: reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Child Behavior Checklist for clinician report. J Clin Psychol 2004; 60:65–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Russ E, Heim A, Westen D: Parental bonding and personality pathology assessed by clinician report. J Personal Disord 2003; 17:522–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Westen D, Muderrisoglu S: Reliability and validity of personality disorder assessment using a systematic clinical interview: evaluating an alternative to structured interviews. J Personal Disord 2003; 17:350–368Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Shedler J, Westen D: Dimensions of personality pathology: an alternative to the five-factor model. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1743–1754Link, Google Scholar

35. Butcher J, Perry J, Atlis M: Validity and utility of computer-based test interpretation. Psychol Assess 2000; 12:6–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Pepper CM, Klein DN, Anderson RL, Riso LP, Ouimette PC, Lizardi H: DSM-III-R axis II comorbidity in dysthymia and major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:239–247Link, Google Scholar

37. Riso LP, Klein DN, Ferro T, Kasch KL, Pepper CM, Schwartz JE, Aronson TA: Understanding the comorbidity between early-onset dysthymia and cluster B personality disorders: a family study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:900–906Link, Google Scholar

38. Westen D, Shedler J: A prototype matching approach to personality disorders: toward DSM-V. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:109–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, Baumann BD, Baity MR, Smith SR, Price JL, Smith CL, Heindselman TL, Mount MK, Holdwick DJ Jr: Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1858–1863Link, Google Scholar

40. Westen D, Shedler J, Durrett C, Glass S, Martens A: Personality diagnoses in adolescence: DSM-IV axis II diagnoses and an empirically derived alternative. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:952–966Link, Google Scholar

41. Blais M, Norman D: A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV personality disorder criteria. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:168–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Meyer GJ, Finn SE, Eyde LD, Kay GG, Moreland KL, Dies RR, Eisman EJ, Kubiszyn TW, Read GM: Psychological testing and psychological assessment: a review of evidence and issues. Am Psychol 2001; 56:128–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Rosenthal R: Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1991Google Scholar

44. Kernberg O: Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. Northvale, NJ, Jason Aronson, 1975Google Scholar

45. Widiger T, Frances A: Toward a dimensional model for the personality disorders, in Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Edited by Costa P, Widiger T. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994, pp 19–39Google Scholar

46. Zanarini M, Parachini E, Frankenburg F, Holman J, Hennen J, Reich D, Silk K: Sexual relationship difficulties among borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003; 191:479–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Kisiel C: Borderline personality disorder: a review of data on DSM-III-R descriptions. J Personal Disord 1991; 5:340–352Crossref, Google Scholar

48. Widiger TA, Costa PT, McCrae RR: A proposal for axis II: diagnosing personality disorders using the five-factor model, in Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality, 2nd ed. Edited by Costa PT, Widiger TA. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2002, pp 431–456Google Scholar

49. Trull TJ: Structural relations between borderline personality disorder features and putative etiological correlates. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:471–481Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar