Reliability and Validity of DSM-IV Axis V

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated the reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and two experimental DSM-IV axis V global rating scales, the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. METHOD: Forty-four patients admitted to a university-based outpatient community clinic were rated by trained clinicians on the three DSM-IV axis V scales. Patients also completed self-report measures of DSM-IV symptoms as well as measures of relational, social, and occupational functioning. RESULTS: The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale, and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale all exhibited very high levels of interrater reliability. Factor analysis revealed that the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale are each more related to the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale individually than they are to each other. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale was significantly related to concurrent patient responses on the SCL-90-R global severity index. The Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale was significantly related to concurrent patient responses on the SCL-90-R global severity index and to a greater degree with both the Social Adjustment Scale global score and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score. Although the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale was not significantly related to any of the three self-report measures, it was related to the presence of clinician-rated axis II pathology. CONCLUSIONS: The three axis V scales can be scored reliably. The Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale evaluate different constructs. These findings support the validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale as a scale of global psychopathology; the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale as a measure of problems in social, occupational, and interpersonal functioning; and the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale as an index of personality pathology. The authors discuss further refinement and use of the three axis V measures in treatment research.

Axis V was introduced to the multiaxial system in DSM-III and modified to the current format of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale in DSM-III-R. Originally the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale was developed from a rating scale for evaluating overall functioning of a patient operationalized in terms of health or sickness (1–3). Subsequently this measure was revised as the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) for the evaluation of overall severity of psychiatric disturbance (4), and it was a modified version of the GAS, the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, that was included in DSM-III-R.

Although axis V, a measure of overall severity of psychiatric disturbance, has the advantage of being a summary score that allows for a clinically meaningful index of global psychopathology, a review of the research on axis V by Goldman et al. (5) reveals moderate reliability and validity, but little of the research focuses specifically on axis V. The first specific problem identified in this review of axis V research is that the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale combines evaluation of symptoms as well as relational, social, and occupational functioning on a single axis. It is important that the contribution of psychiatric symptoms be separable from relational, social, and occupational functioning.

In its current format, the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale may have considerable overlap with axes I and II, and this may limit the utility of axis V. Assessment of functioning beyond psychiatric symptoms seems relevant to a comprehensive diagnosis so as not to be redundant with axes I and II. A separation of axes I and II symptoms from the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale is important if a distinct measure of global functioning is to be achieved.

The second problem discussed by Goldman et al. (5) is the exclusion of physical impairments from the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. An examination of the divergence and convergence of an individual’s general medical condition with his or her social and occupational functioning is also necessary. Goldman et al. suggested a modified version of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale that separated relational functioning from the measure of symptoms and psychological functioning into one scale (the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning) and social and occupational functioning into another (the Social and Occupational Assessment Scale). Goldman et al. further suggested that the two new measures be used with the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale in field testing, along with new instructions allowing the rating of physical impairments as well as psychological ones. In addition, these authors noted that studies examining the impact of training on the reliability of axis V are needed.

In DSM-IV, the latest revision of DSM, efforts were made to incorporate these suggestions by adding the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale in Appendix B (pp. 758–761). These two new experimental global functioning scales on axis V were provided for further study. It is hoped that they will improve the performance of the multiaxial system to assess different domains of functioning and provide incremental information regarding patients to clinicians. In addition, these two scales were developed to provide researchers and clinicians with tools to examine domains that were independent of symptoms and/or psychological impairment.

The Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale is used to evaluate the individual’s functioning in relationships with family, friends, and significant others. This scale relates the degree of relational functioning from optimal to disrupted by using the three major content areas of problem solving, organization, and emotional climate.

The Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale is designed to assess an individual’s level of social and occupational functioning not directly influenced by the overall severity of psychiatric symptoms. This scale also considers the effects of the individual’s general medical condition in the evaluation of social and occupational functioning.

These two experimental scales are thought to provide different and independent types of clinical information beyond that provided by the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. This separation of psychiatric symptoms from the rating of social and occupational functioning may reduce confusion regarding the ratings of these domains, increase reliability, and increase clinical information relevant for treatment planning and evaluation. A more multidimensional assessment of relational, social, and occupational functioning in individuals is likely to be superior to an evaluation of symptom severity alone.

The current study is distinctive because to our knowledge it is the first to evaluate the nature of the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and Social and the Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. Specifically, we evaluated the interrater reliability of these two experimental scales. We explored the dimensions underlying these rating scales as well as the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and examined the characteristics that were most useful in understanding the similarities and differences among these three axis V scales.

We examined the relationship between each of the three scales and the presence of axis II pathology as well as self-report measures of DSM-IV symptoms and relational, social, and occupational functioning. The use of self-report scales assessing similar constructs of global distress or symptoms (i.e., the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale), social/occupational functioning (i.e., the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale), and interpersonal functioning (i.e., the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale) will aid in determining the validity of the three clinician-rated scales.

Method

Participants

All participants were representative of those seeking outpatient treatment at a university-based community clinic. Patients were assigned to treatment teams and treating clinicians on the basis of their needs and clinician availability and caseloads. Moreover, patients were accepted into treatment regardless of disorder or comorbidity. At any time during the 22-month period of data collection for this study, the number of supervised treatment protocols at this clinic ranged from three to five.

The participants were 44 patients consecutively admitted to one of two treatment teams over a 22-month period; 20 patients were male, 24 were female; 22 were single, 11 were married, and 11 were divorced. The patients’ mean age was 29.2 (SD=11.2). The DSM-IV axis I diagnoses included mood disorder (N=25), anxiety disorder (N=1), substance-related disorder (N=2), adjustment disorder (N=4), and V-code-relational problem (N=10). (Two patients did not have an axis I diagnosis but did have an axis II diagnosis.) In addition, 15 individuals were diagnosed as having a DSM-IV personality disorder, and eight were diagnosed as having personality disorder features or traits. Each participant provided written informed consent to be included in this research.

Procedure

Each participant completed a videotaped semistructured clinical interview that lasted approximately 2 hours and an interpretive/feedback interview that lasted approximately 1 hour. The clinical interview focused on such therapeutic topics as presenting problems; past psychiatric history; past medical history; family history; developmental, social, educational, and work history; and exploration of both past and current relational episodes. The interview also included a mental status examination with assessment of all DSM-IV symptom criteria for schizophrenia, major depressive/manic/mixed episode, dysthymia, and many anxiety symptoms. Each feedback session, also videotaped, was organized according to a therapeutic model of assessment (6, 7) in which collaboration, alliance building, exploration of factors maintaining life problems (often relational) with the identification of potential solutions, and therapist-patient interaction were a focus.

Ten advanced students (five men and five women) enrolled in a clinical psychology Ph.D. program (approved by the American Psychological Association) conducted the psychological assessment, feedback sessions, and ratings of DSM-IV axis V scales. All clinicians had completed graduate course training in descriptive psychopathology and were supervised by a licensed Ph.D.-level clinical psychologist with several years of applied experience.

Before rating the DSM-IV axis V scales for this study, the 10 clinicians participated in both individual and group training on scoring that included review of scoring guidelines for each of the three variables of interest. The scales included the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale, and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. DSM-IV axis V rating scales (i.e., ratings on a scale of 0 to 100) were based on the level of functioning of patients at the time of evaluation. All of the rating scales used in this study were scored by the clinician conducting the assessment immediately at the end of the feedback session and were based on information gained during both the clinical interview and feedback sessions.

An external rater then independently scored all rating scales used in this study for each participant immediately after viewing a videotape of both the clinical interview and feedback sessions. For all cases, scoring of the scales by the second rater was completed independent of patient diagnosis, self-report data, and the assessing clinician’s ratings for the three scales. In addition, each clinician received a minimum of 3.5 hours of supervision per week (1.5 hour individually and 2 hours in a group treatment team meeting) on the therapeutic assessment model/process, scoring/interpretation of assessment measures, clinical interventions, and presentation/organization of collaborative feedback.

Self-Report Measures

Participants were asked to complete the SCL-90-R (8), the Social Adjustment Scale (9), and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (10) during the assessment process. These questionnaires all have summary scores (i.e., SCL-90-R global severity index, Social Adjustment Scale global score, and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score) that serve as measures of global psychopathology and overall level of problems in social or interpersonal functioning. Before administering these self-report inventories, the clinician explained to the patient how completing these measures as openly as possible would aid in a better understanding of the patient’s current life problems as well as facilitate the development of treatment goals. The patient independently completed the self-report measures; however, the clinician was available in the clinic to the patient to answer any questions that arose during the testing. Before scoring the assessment measures used in this study, the 10 clinicians participated in both individual and group training where scoring and interpretation guidelines were reviewed.

Data Analyses

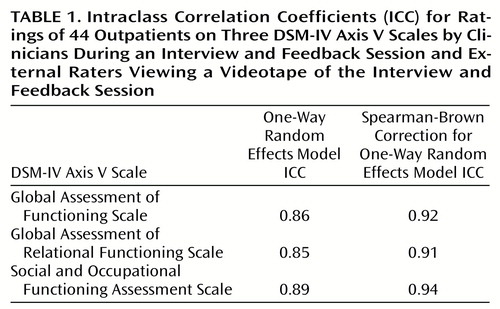

The interrater reliability of the DSM-IV axis V scales (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale, and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale) were evaluated by using one-way random effects model intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (11) for each assessment protocol (i.e., clinical interview and feedback session) rated by the clinician conducting the assessment and an external rater. Additionally, the Spearman-Brown correction for a one-way random effects model ICC was calculated to examine the reliability of the mean score for each DSM-IV axis V scale used in the study, representing the average across each different pair of raters. Intraclass correlation coefficients are considered excellent if greater than 0.74, good if ranging from 0.60 to 0.74, and fair if ranging from 0.40 to 0.59 (12).

A principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation was performed on the clinician and external rater scores for the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale, and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale to assess the degree that these scales measured similar or different constructs. In addition, the Pearson r correlation was used to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of the three scales with one another. The final analyses examined the convergent and discriminant validity of the three axis V scales with the self-report measures of global psychopathology (SCL-90-R global severity index), social impairment (Social Adjustment Scale global score), and interpersonal functioning (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score) as well as an index of personality pathology.

To assess the presence of axis II psychopathology in a dimensional manner, patients who were classified by the clinical team as having a personality disorder diagnosis (N=15) were assigned a value of 2, those who had subclinical features/traits of a personality disorder (N=8) were assigned a value of 1, and those with no evidence of axis II psychopathology (N=21) were assigned a value of 0.

Results

Both clinician and external rater mean scores for the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (mean=64.5, SD=7.1, and mean=62.5, SD=6.9, respectively) and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (mean=62.6, SD=10.7, and mean=62.7, SD=8.3, respectively) were in the mild-to-moderate range of symptoms/difficulty. The clinician and external rater mean scores for the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale (mean=52.2, SD=15.1, and mean=51.1, SD=12.2, respectively) were in the clearly dysfunctional range of functioning.

DSM-IV Axis V Scales: Reliability

The positive psychometric properties of the DSM-IV axis V scales were supported by the results of this study. The reliability ICCs (one-way random effects model) of the three DSM-IV axis V scales are shown in Table 1; they were all in the excellent range (ICC>0.74). Spearman-Brown-corrected interrater reliability ICCs for the three scales are also presented in Table 1; all were in the excellent range.

DSM-IV Axis V Scales: Convergent and Discriminant Validity

The relationship between the clinician and external rater scores for the axis V variables was examined by using a principal components factor analysis with orthogonal/varimax rotation. The number of factors retained was determined by inspection of eigenvalues, the root curve criterion, and the scree test. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 2. In factor 1, the primary loadings were the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale scores of the clinician and the external rater, but clinician and external rater Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale scores exhibited primary loadings on factor 2. Clinician and external rater Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores exhibited almost identical moderate loadings on both factor 1 and factor 2. Factor 1 had an eigenvalue of 3.9, accounting for 65% of the variance, while factor 2 had an eigenvalue of 1.3, accounting for an additional 21% of variance. An oblique factor rotation was also conducted using the same variables; this analysis revealed the same number of factors, the same variables in each of the factors, and that the variables were distributed in the same magnitude.

In all further analyses the Spearman-Brown-corrected interrater reliability ICCs for the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale, and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale representing the mean scores of the clinician and external rater were used. The relationship of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale to the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale (r=0.60, N=44, p<0.0001) was identical to its relationship to the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (r=0.60, N=44, p<0.0001); this relationship was moderate to strong in magnitude. However, the association between the two experimental scales was low (r=0.34, N=44, p=0.02).

The relationships between the DSM-IV axis V scales and the presence of axis II pathology and three patient self-report measures are shown in Table 3. Negative correlations indicate a relationship between higher scores (i.e., greater problems or psychopathology) on both the self-report measures and the personality disorder index (range=0–2) and lower scores (i.e., greater problems or psychopathology) on the three DSM-IV axis V scales.

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores were found to be significantly related to the SCL-90-R global severity index, indicating that as ratings of patients’ global level of functioning went down (i.e., became more severely symptomatic) the patients concurrently reported a greater severity of symptoms on the SCL-90-R. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale was also found to be significantly related to clinician-rated personality problems on the personality disorder index but not significantly related to either the Social Adjustment Scale global score or the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score.

The Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale was found to be significantly related to clinician ratings of axis II psychopathology on the personality disorder index but not significantly related to any of the three self-report measures of global psychopathology (SCL-90-R global severity index) or overall level of problems in social (Social Adjustment Scale global score) or interpersonal functioning (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score). Although significantly related to the SCL-90-R global severity index and personality disorder index, the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale exhibited a greater relationship to both the Social Adjustment Scale global score and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score. These significant relationships indicate that as ratings of patients’ social and occupational functioning went down (i.e., became more impaired or difficult), those patients concurrently reported a greater number of problems in their social adjustment (Social Adjustment Scale global score) and interpersonal relationships (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale as well as the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and Social and the Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, two experimental DSM-IV axis V scales, can be reliably scored. All three scales exhibited reliability in the excellent range (ICC>0.74). This provides confidence in the current scoring criteria and definitions for the three scales. However, during the course of training and data collection, a number of the clinicians expressed a desire for the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale to be separated in 10-point criteria/definition segments similar to the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. In addition, there was some confusion as to how much to weight “family” or “significant other” relationships when both were present and differences in functioning existed between the two. We would submit these two suggestions when future revisions of this scale are attempted and wonder if such changes would increase the external validity of the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale. Despite these two concerns, the clinicians in the study rated the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale with a very high level of reliability.

A second goal of this study was to assess the degree to which the two experimental scales are measuring different constructs from the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and each other. Results of the factor analysis revealed that the clinician and external rater scores for the axis V variables formed two factors, and these factors accounted for 86% of the total variance. Although we used an orthogonal rotation to obtain maximum factor independence, the clinician and external rater Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores demonstrated remarkably similar loadings on each of the factors.

This multiple loading by Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores suggests that both factors are significantly related to global levels of symptoms and functioning. This indicates support for the presence of two subtypes of global distress or psychopathology. Factor 1 appears to represent a social and occupational impairment facet of general psychopathology, and factor 2 appears to tap a facet of general psychopathology representing relational disturbance. Although the correlation between factor 1 and factor 2 was significant (r=0.32, p=0.04), it shows only a limited relationship between the two factors and indicates that there is some distinction between these elements of global psychopathology. Therefore, it appears that when global assessment of functioning is assessed, both of these factors—social-occupational and interpersonal functioning—should be considered in the evaluation.

The results of this study suggest that the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale are each more related to the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale individually than they are to each other. So it would appear that these two scales are evaluating something different from one another and to a lesser extent from the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Since the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale appear to be measuring different (albeit related) constructs, an additional analysis of this study was to evaluate the relationship of each of the three axis V scales with the three self-report measures of psychopathology and clinical ratings of axis II psychopathology. In these analyses we found a large relationship between patient self-reported problems in social adjustment and interpersonal relationships and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale showed the largest significant relationship to a patient’s report of psychiatric symptoms (SCL-90-R global severity index), but it did not show a specific significant association with social impairment (Social Adjustment Scale global score) or interpersonal impairment (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score). Although the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale did not show the anticipated relationship with interpersonal functioning (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total score), this scale showed a robust association with clinician ratings of axis II personality pathology (personality disorder index).

One limitation of this study was the use of patients from a university-based community outpatient clinic where most patients exhibited mild-to-moderate levels of psychiatric disturbance. The use of the such subjects may have restricted the range of patient functioning, and studies examining the psychometric properties of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale, and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale with inpatient populations will be necessary to further support the effectiveness/utility of these axis V scales. However, the ecological validity of this group of patients should increase the generalizability of these findings to groups from other university-based outpatient community clinics.

Another potential factor that could have had an adverse impact on the reliability ratings of the three axis V scales was the fact that the two raters did not have the same experience with the patient whom they scored. One rater had a face-to-face interaction with the patient, and the second rater based the rating on a videotape of this clinician-patient interaction. Although ratings of two clinicians who were both present during the same interview and feedback sessions might have led to higher levels of reliability, it appears that the information conveyed on the videotape of the interview and feedback sessions was sufficient for the two raters in this study to achieve excellent levels of reliability (ICC>0.74). In addition, the factor analysis shows that the three clinician rating scales converged on the two factors in a similar manner regardless of which source (i.e., clinician and interview or external rater and videotape) provided the rating.

Future studies should also ascertain whether the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale can be used effectively as outcome variables in treatment studies. Such findings on clinical utility would support the further use of the two experimental scales. The findings of the present study support the use of the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale as useful scales in evaluating changes in personality psychopathology as well as social adjustment and interpersonal relationships (respectively) during a treatment protocol.

|

|

|

Received June 28,1999; revisions received Dec. 14, 1999, and July 12, 2000; accepted July 17, 2000. From the Department of Psychology, University of Arkansas. Address correspondence to Dr. Hilsenroth, 216 Memorial Hall, Department of Psychology, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Luborsky L: Clinicians’ judgments of mental health. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1962; 7:407–417Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Luborsky L, Diguer L, Luborsky E, McLellan A, Woody G, Alexander L: Psychological health-sickness (PHS) as a predictor of outcomes in dynamic and other psychotherapies. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993; 61:542–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Luborsky L, Diguer L, Cacciola J, Barber J, Moras K, Schmidt K, DeRubeis R: Factors in outcomes of short-term dynamic psychotherapy for chronic vs nonchronic major depression. J Psychother Pract Res 1996; 5:152–159Medline, Google Scholar

4. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1148–1156Google Scholar

6. Finn S, Tonsager M: Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: complementary paradigms. Psychol Assess 1997; 19:374–385Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Finn S, Tonsager M: Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to college students awaiting therapy. Psychol Assess 1992; 4:278–287Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 3rd ed. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1994Google Scholar

9. Weissman M, Bothwell S: Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1111–1115Google Scholar

10. Horowitz L, Rosenberg S, Baer B, Ureno G, Villasenor V: Inventory of Interpersonal Problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:885–892Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Shrout P, Fleiss J: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:420–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fleiss J: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1981Google Scholar