Comparative Mortality Associated With Ziprasidone and Olanzapine in Real-World Use Among 18,154 Patients With Schizophrenia: The Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC)

Abstract

Objective:

The authors compared 1-year mortality rates associated with ziprasidone and olanzapine in real-world use.

Method:

The Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC) was an open-label, randomized, postmarketing large simple trial that enrolled patients with schizophrenia (N=18,154) in naturalistic practice in 18 countries. The primary outcome measure was nonsuicide mortality in the year after initiation of assigned treatment. Patients were randomly assigned to receive treatment with either ziprasidone or olanzapine and followed for 1 year by unblinded investigators providing usual care. A physician-administered questionnaire was used to collect baseline demographic information, medical and psychiatric history, and concomitant medication use. Follow-up information on hospitalizations and emergency department visits, patients' vital status, and current antipsychotic drug status was collected and reported by treating psychiatrists. Post hoc analyses of sudden death, a secondary endpoint, were also conducted.

Results:

The incidence of nonsuicide mortality within 1 year of initiating pharmacotherapy was 0.91 for ziprasidone (N=9,077) and 0.90 for olanzapine (N=9,077). The relative risk was 1.02 (95% CI=0.76–1.39). This finding was confirmed in numerous secondary and sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions:

Despite the known risk of QTc prolongation with ziprasidone treatment, the findings of this study failed to show that ziprasidone is associated with an elevated risk of nonsuicidal mortality relative to olanzapine in real-world use; the study excludes a relative risk larger than 1.39 with a high probability. However, the study was neither powered nor designed to examine the risk of rare events like torsade de pointes.

Patients with schizophrenia have an elevated mortality rate (1, 2). Whether mortality rates vary among patients receiving different drugs, however, is unclear (3, 4). The literature largely comprises relatively brief, small, well-controlled randomized clinical trials with selective patient inclusion criteria.

Large simple trials, also known as large pragmatic trials, large streamlined studies, and practical clinical trials, have been employed to examine important public health questions about the benefits and risks of medications in routine medical practice settings for decades in cardiac mortality (5), head injury (6), analgesic effects (7), and AIDS (8), among other applications. Such studies use patient samples in the thousands, randomization, broad entry criteria, streamlined assessments consistent with routine practice, and definitive endpoints (such as death or hospitalization). The need for large simple trials in psychiatry is increasingly recognized as such studies constitute a major means of examining the balance between benefit and harm in treatments as they are administered in clinical practice (9).

QTc prolongation is of clinical concern because of its potential to induce torsade de pointes and other serious ventricular arrhythmias that can result in sudden death. Drugs associated with the risk of a greater degree of QTc prolongation than ziprasidone have been shown to increase the risk of sudden death, mainly when used at high doses (10, 11). At the time of ziprasidone's initial approval in the United States and Sweden in 2000 and 2001, questions remained as to whether the modest QTc prolongation associated with the drug would translate to increased mortality in patients using it. Because the number of patients exposed to ziprasidone at the time of marketing authorization was too small to allow for estimation of QT-related effects, and because such studies would not reflect real-world prescribing practices, another study was initiated to provide safety assurance for the use of the drug. The Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC) was a postapproval commitment by Pfizer, Inc., to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Swedish Medical Products Agency.

ZODIAC was an international, multicenter, randomized large simple trial designed to examine the risks of nonsuicide mortality and hospitalization associated with ziprasidone and olanzapine, another atypical antipsychotic, in the context of usual clinical treatment. Olanzapine was selected as the comparator in the study because it was not linked to QTc prolongation in the literature or in a carefully controlled pharmacokinetic study of several agents compared with ziprasidone (12). The main objective of ZODIAC was to evaluate mortality, which limited the study's ability to provide data on drug efficacy. Because the metabolic risks associated with olanzapine were not fully realized when ZODIAC was designed, measures of metabolic parameters were not systematically collected.

Method

ZODIAC's design has been presented in detail elsewhere (13) and is only summarized here. Initial analyses of the primary endpoint, nonsuicide mortality, and secondary endpoints were conducted according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan. Further post hoc analyses of sudden death, a secondary endpoint, were conducted in response to later questions from the FDA.

Study Design

Participants were assigned to receive treatment with ziprasidone or olanzapine in a strictly random 1:1 fashion (within each country), after which no further protocol-mandated interventions were made. Neither the physician nor the patient was blind to the treatment allocation, consistent with routine medical care. Physicians and patients were free to change regimens and dosing based on patients' responses to the assigned medication, and use of concomitant medications, including other antipsychotics, was permitted. Dosing guidance was provided to all participating physicians via locally approved labeling. No attempts were made to influence or monitor the dosages prescribed, and specific information on dosing of study medications throughout the study period was not systematically collected, so as to minimize study burden on physicians and patients. ECGs were not required at baseline or during the course of the study and were done only as clinically indicated and as consistent with usual practice.

Participants

Patients newly treated for schizophrenia and those receiving continuing treatment were eligible if their treating psychiatrist was ready to initiate a new antipsychotic medication and would consider using either ziprasidone or olanzapine as an appropriate therapy. To be eligible for the study, patients had to be age 18 or older; be treated in an inpatient or outpatient setting; be diagnosed as having schizophrenia according to the treating physician's clinical judgment; provide signed and dated informed consent; be willing to provide the name of at least one contact person for study staff to contact regarding the patient's whereabouts should the patient be lost to follow-up over the course of the study; and, among U.S. patients, be willing to provide their Social Security number. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating; were participating in any other studies involving investigational products, concomitantly or within 30 days before entry in the study; had a progressive fatal disease or a life expectancy that would prohibit participation in a 1-year research study; or were previously enrolled in this study and randomized to a study medication.

Study Outcome Measures and Endpoint Adjudication

Each participant was to be followed for 1 year, regardless of how long he or she remained on randomized treatment. Information on the patient's vital status, the patient's continued use of the assigned study drug as indicated on study questionnaires, and whether the patient was hospitalized was obtained through follow-up with the treating physician or another designated member of the medical care team. Medical records and other documentation, where applicable, were obtained for endpoint screening and coding purposes. In the event that the participant could not be contacted, his or her alternative contact was used. In the United States, the National Death Index was also searched for information on vital status for participants lost to follow-up.

The primary outcome measure was nonsuicide mortality; secondary endpoints included sudden death, suicide, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and -hospitalization for arrhythmia (including arrhythmia reported during hospitalization for other reasons), diabetic ketoacidosis, and myocardial infarction. Discontinuation of randomized treatment as recorded on study questionnaires was also a secondary endpoint.

All fatal events and hospitalizations were reviewed by the chair of the Endpoint Committee, who was blind to treatment allocation, for classification into one of three categories: a “potential study endpoint,” an “endpoint with insufficient data,” or “not a potential study endpoint.” All “potential study endpoints” were placed into one of six categories (myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, sudden death, diabetic ketoacidosis, suicide, or fatal event with other cause) for detailed review and endpoint determination by Endpoint Committee experts in the fields of psychiatry, cardiology, and endocrinology from the regions participating in the study. Two expert coders, blind to treatment allocation, reviewed anonymized records (e.g., medical records, laboratory data, hospital discharge or admission notes, and death certificates) specific to each event. A final study diagnosis with level of certainty (“definite,” “possible,” “no indication of endpoint,” and “insufficient data to determine diagnosis”) was assigned for each event according to prespecified algorithms (available on request from the first author) and expert consensus. Final endpoint codes were assigned by the Endpoint Committee chair.

The cardiovascular endpoint was a composite endpoint comprising myocardial infarction and arrhythmia. The three main components of the endpoint algorithm for myocardial infarction, which was based on criteria used in the World Health Organization Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease study (14), were the following: symptoms, including chest pain; enzyme levels, including creatine phosphokinase, LDH, and SGOT; and ECG readings. Fatal myocardial infarction events were also further classified according to available autopsy findings.Potential myocardial infarction events were classified as follows:

| •. | “Myocardial infarction, definite” if there were definite changes in serial ECGs or if the symptoms were typical; if symptoms were atypical or inadequately described, ECG results indicated a probable myocardial infarction, and abnormal enzyme levels were documented; or if symptoms were typical and enzyme levels were abnormal with ECG results either atypical, uncodable, or not available. | ||||

| •. | “Myocardial infarction, possible” if information on typical symptoms, consistent with myocardial infarction, was available but no information on enzymes and ECG was available. | ||||

Fatal potential myocardial infarction events were also classified on the basis of available autopsy fi ndings, as follows:

| •. | “Fatal myocardial infarction, definite” if criteria for definite myocardial infarction were met and if myocardial infarction was documented in autopsy fi ndings. | ||||

| •. | “Fatal myocardial infarction, possible” if there were symptoms indicative of myocardial infarction but no autopsy was performed; or if an unexplained death occurred in a patient who had prior cardiovascular disease. | ||||

| •. | “Fatal myocardial infarction, insufficient data” if data were incomplete on symptoms, enzyme levels, and ECGs (this category was frequently applied to unwitnessed fatal events that occurred outside the hospital, and many fatal events were so categorized solely on the basis of nonspecifi c information from death certifi cates suggesting that the patient may have died from cardiac causes). | ||||

The endpoint algorithm used to identify arrhythmia endpoints was based on two components: previous history of arrhythmia and ECG readings. Potential arrhythmia events were classifi ed as follows:

| •. | “Arrhythmia, definite” if ECG tracings were consistent with torsade de pointes, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, other life-threatening arrhythmia, or other arrhythmias. | ||||

| •. | “No arrhythmia endpoint” if arrhythmia was suspected but there was no evidence of arrhythmia on ECG; or if arrhythmia was suspected and confi rmed on ECG but the patient had a prior history of arrhythmia before entering the study. | ||||

| •. | “Arrhythmia, insufficient data” if arrhythmia was suspected but ECGs either were not available or were not of sufficient quality for coding arrhythmia. | ||||

The suicide mortality endpoint algorithm was based on the following: history of suicide attempt or known suicidal tendencies and description of the event (e.g., suicide note, documentation of method used). Events were coded as follows:

| •. | “Suicide, definite” if there were previously documented suicide attempts, a suicide note was discovered, and an accidental cause of death could be excluded. | ||||

| •. | “Suicide, possible” if there was suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempt or no suicide note found and an accidental cause of death could be excluded. | ||||

| •. | “Suicide, insufficient data” if the documentation was unclear regarding prior suicidality. | ||||

Sudden death was defined as death verified to have occurred within 1 hour of onset of symptoms. Only those cases initially classified at screening as cardiac deaths by the Endpoint Committee hair were initially evaluated for sudden death. All mortality events were later rescreened in response to the FDA's request to adjudicate sudden deaths using the ICD-10 coding system.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis specified in advance was intent to treat, with outcomes assessed over the full 1-year follow-up period and based on the study medication to which patients were assigned, regardless of how long they remained on randomized treatment. A secondary analysis based on person-time on assigned treatment was planned, which included only events occurring while patients were recorded to have been continuing randomized medication plus a grace period of 30 days; the denominator for incidence rates from this secondary analysis was patient-years on randomized treatment.

Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for primary (nonsuicide mortality) and secondary (all-cause, cardiovascular, and suicide mortality; sudden death; all-cause hospitalization and hospitalization for myocardial infarction, arrhythmia [or arrhythmia reported during hospitalization for other reasons], or diabetic ketoacidosis) endpoints, comparing their incidence in the ziprasidone group with that in the olanzapine group. Sensitivity analyses to account for missing data due to premature withdrawal included examination of patients who died or who had at least 11.5 months of follow-up; and estimation of hazard ratios and their 95% CIs for time to nonsuicide mortality through 1 year, using Cox proportional hazards regression modeling. Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to study medication discontinuation were also computed, along with 95% CIs, to calculate proportions of participants remaining on study medication at the end of 6 and 12 months, which was an additional secondary endpoint.

Sample size estimation in the protocol assumed that the rate of nonsuicide mortality was 2% per patient-year, that a relative risk of 1.5 was the clinically relevant effect estimate, and that participants would only be in the study for 6 months. Based on these assumptions, it was estimated that 9,000 participants were needed in each treatment arm to give the study 85% power (for the primary analysis) with a two-sided type I error rate of 0.05. In other words, following 18,000 participants for a full year would allow 85% power to detect a relative risk of 1.3.

The study was reviewed by the St. Davids Human Research Review Board (Radnor, Pa.), the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (Philadelphia), 125 local institutional review boards in the United States, and institutional review boards in each of the participating countries.

Results

A total of 18,239 patients with physician-diagnosed schizophrenia from community mental health clinics, private psychiatric practices, residential care facilities, and academic treatment centers in 18 countries were randomly assigned to treatment with ziprasidone or olanzapine between February 2002 and March 2007. Through routine site monitoring and sponsor quality assurance visits, 0.4% (N=85) of participants were identified as having protocol violations (e.g., did not sign informed consent form, did not meet inclusion criteria, met exclusion criteria) that warranted exclusion of their data from analyses. This left a total sample size of 18,154 for analytic purposes. Sensitivity analyses were carried out to examine the impact other protocol violations had on the primary endpoint in the intent-to-treat analysis, ranging from more serious (e.g., the participant did not meet the predefined inclusion or exclusion criteria) to less serious (e.g., the participant did not initial every page of the informed consent form); the results from these analyses (with sample sizes ranging from N=17,853 excluding only more serious protocol violations to N=16,913 excluding both more serious and less serious protocol violations) were very similar to the results for the full analytic population and are not presented.

The majority (72.6%) of patients in the study were enrolled in the United States and Brazil, followed by other Latin American countries (16.4%), Europe (5.9%), and Asia (5.1%). The patients' mean age was 41.1 years (SD=13.0); 55% were male, over half (59.9%) were Caucasian, and 17.2% were black; demographic characteristics were balanced by treatment arm (Table 1). Treatment groups were also balanced with respect to various measures of prior psychiatric disease. Most patients (75.2%) had been hospitalized in an inpatient psychiatric unit at some point, and nearly one-third (30.0%) had attempted suicide in the past. In general, previous cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors were balanced by treatment arm. However, history of hypertension at baseline was a bit more frequent in patients in the ziprasidone group than in those in the olanzapine group (18.6% and 16.6%, respectively; p<0.001).

| Characteristic | Ziprasidone Group (N=9,077) | Olanzapine Group (N=9,077) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Mean age (years) | 41.2 | 13.0 | 40.9 | 13.1 |

| Mean Clinical Impression Scale score | 4.2 | 1.05 | 4.2 | 1.04 |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Male | 4,866 | 54.8 | 4,895 | 55.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 5,418 | 60.0 | 5,379 | 59.6 |

| Black | 1,551 | 17.2 | 1,546 | 17.1 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 634 | 7.0 | 622 | 6.9 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 550 | 6.1 | 564 | 6.3 |

| Other | 871 | 9.7 | 910 | 10.1 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 154 | 1.7 | 131 | 1.4 |

| Stroke | 165 | 1.8 | 156 | 1.7 |

| Hypertension | 1,687 | 18.6 | 1,504 | 16.6 |

| Coronary artery disease or angina | 231 | 2.5 | 214 | 2.4 |

| Arrhythmia | 268 | 3.0 | 265 | 2.9 |

| High cholesterol or triglyceride levels | 1,364 | 15.0 | 1,316 | 14.5 |

| Diabetes | 703 | 7.7 | 696 | 7.7 |

| Past psychiatric inpatient hospitalization | 6,826 | 75.2 | 6,828 | 75.2 |

| Past suicide attempt | 2,676 | 29.5 | 2,759 | 30.4 |

| Past use of ziprasidone | 1,008 | 11.1 | 1,003 | 11.0 |

| Past use of olanzapine | 2,867 | 31.6 | 2,806 | 30.9 |

TABLE 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC), 2002-2007a

Mortality Endpoints

A total of 205 deaths occurred in the full intent-to-treat study population, comprising 1.1% of the randomized study population (Table 2). There was no difference between the ziprasidone and olanzapine treatment arms with respect to the primary endpoint of nonsuicide mortality (relative risk=1.02, 95% CI=0.76–1.39). Sensitivity analyses for the primary analysis of nonsuicide mortality were performed, employing multiple techniques to account for missing data due to premature withdrawal of patients. The results of these sensitivity analyses yielded nearly identical findings (data not shown), suggesting that the primary intent-to-treat analyses were robust. The secondary analyses based on person-time on assigned treatment yielded a relative rate for nonsuicide mortality of 1.03 (95% CI=0.74–1.45), consistent with the primary analysis results. Each variable listed in Table 1 was entered separately into this analysis and failed to substantively influence the olanzapine versus ziprasidone difference (data available on request). Stratification by geographic region showed consistent results in all regions (p value for interaction, 0.20).

| Endpoint | Ziprasidone Group | Olanzapine Group | Ratio | Total Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis: intent-to-treat | N=9,077M | N=9,077 | N=18,154 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | Risk Ratio | 95% CI | N | % | |

| Nonsuicide mortality | 83 | 0.91 | 81 | 0.90 | 1.02 | 0.76-1.39 | 164 | 0.90 |

| All-cause mortality | 103 | 1.13 | 102 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 0.77-1.33 | 205 | 1.13 |

| Cardiovascular mortalitya | ||||||||

| Endpoints narrowly defined | 3 | 0.03 | 8 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.10-1.41 | 11 | 0.06 |

| Endpoints broadly defined | 24 | 0.26 | 15 | 0.17 | 1.60 | 0.84-3.05 | 39 | 0.21 |

| Mortality due to suicideb | ||||||||

| Endpoints narrowly defined | 19 | 0.21 | 16 | 0.18 | 1.19 | 0.61-2.31 | 35 | 0.19 |

| Endpoints broadly defined | 21 | 0.23 | 21 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.55-1.83 | 42 | 0.23 |

| Sudden deathc | 2 | 0.02 | 3 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.11-3.99 | 5 | 0.03 |

| Sudden death (post hoc analysis 1)d | 9 | 0.10 | 8 | 0.09 | 1.11 | 0.45-2.77 | 17 | 0.09 |

| Sudden cardiac death (post hoc analysis 2)e | 31 | 0.34 | 31 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.65-1.50 | 62 | 0.34 |

| Secondary analysis: person-time on assigned treatment | Person-Years=6,198 | Person-Years=6,902 | Person-Years=13,100 | |||||

| N | Ratef | N | Ratef | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | N | Ratef | |

| Nonsuicide mortality | 65 | 1.05 | 70 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 0.74-1.45 | 135 | 1.03 |

| All-cause mortality | 82 | 1.32 | 89 | 1.29 | 1.03 | 0.76-1.39 | 171 | 1.30 |

| Cardiovascular mortalitya | ||||||||

| Endpoints narrowly defined | 3 | 0.05 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.19-3.73 | 7 | 0.05 |

| Endpoints broadly defined | 19 | 0.31 | 10 | 0.14 | 2.12 | 0.98-4.55 | 29 | 0.22 |

| Mortality due to suicideb | ||||||||

| Endpoints narrowly defined | 16 | 0.26 | 13 | 0.19 | 1.37 | 0.66-2.85 | 29 | 0.22 |

| Endpoints broadly defined | 17 | 0.30 | 19 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.52-1.92 | 36 | 0.27 |

| Sudden deathc | 1 | 0.02 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.04-3.57 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Sudden death (post hoc analysis 1)d | 8 | 0.13 | 7 | 0.10 | 1.30 | 0.47-3.58 | 15 | 0.11 |

| Sudden cardiac death (post hoc analysis 2)e | 25 | 0.40 | 26 | 0.38 | 1.09 | 0.63-1.89 | 51 | 0.39 |

TABLE 2. One-Year Mortality Incidence, Primary and Secondary Analyses of Mortality Endpoints in the Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC), 2002-2007

In the primary intent-to-treat analyses, no differences were observed with respect to the secondary endpoints of all-cause mortality (relative risk=1.01, 95% CI=0.77–1.33) or mortality due to sudden death (relative risk=0.67, 95% CI=0.11–3.99). As requested by the FDA, a readjudication of all mortality events was conducted using ICD-10 coding for sudden death; these results ranged from a relative risk of 1.11 (95% CI=0.45–2.77) for the narrowest and most specific definition of sudden death (N=17) to 0.99 (95% CI=0.65–1.50) for the broadest (N=62). The secondary analyses based on person-time on assigned treatment also yielded consistent results for these secondary endpoints (all-cause mortality, relative risk=1.03, 95% CI=0.76–1.39; sudden death, relative risk=0.37, 95% CI=0.04–3.57).

For fatal myocardial infarction or fatal arrhythmia events classified by the Endpoint Committee as definite or possible events, the relative risk for cardiovascular mortality comparing ziprasidone (N=3, 0.03%) with olanzapine (N=8, 0.09%) was 0.38 (95% CI=0.10–1.41). When cardiovascular mortality was conservatively expanded to include events categorized as having insufficient data, the relative risk became 1.60 (95% CI=0.84–3.05; N=24 [0.3%] for ziprasidone and N=15 [0.2%] for olanzapine). Restricting these two analyses to person-time on assigned therapy, the relative risk for cardiovascular mortality became 0.84 (95% CI=0.19–3.73; N=3 [0.05 per 100 person-years] for ziprasidone and N=4 [0.06 per 100 person-years] for olanzapine). Conservatively expanding this to include cardiovascular events categorized as having insufficient data, the relative risk became 2.12 (95% CI=0.98–4.55; N=19 [0.31 per 100 person-years] for ziprasi-done and N=10 [0.14 per 100 person-years] for olanza-pine). A detailed post hoc examination of cardiovascular mortality endpoints in the “insufficient data” category indicated that many were unobserved deaths with limited clinical data available. While these were often coded as myocardial infarction on death certificates, leading to their inclusion in the cardiovascular mortality category, the treating physician did not have the predetermined clinical information required to corroborate the diagnosis and mortality classification. Of 28 cardiovascular mortality endpoints classified as “insufficient data” (21 in the ziprasidone group and seven in the olanzapine group), 24 (85.7%) were missing all three criteria (symptoms, enzymes, and ECG) required by the algorithms for myocardial infarction and arrhythmia classification. No cases of torsade de pointes were observed.

With regard to suicide (definite or possible), the relative risk for ziprasidone versus olanzapine was 1.19 (95% CI=0.61–2.31). Conservatively expanding this to include events categorized as “suicide, insufficient data,” the relative risk became 1.00 (95% CI=0.55–1.83). Once again, the secondary analysis of person-time on assigned treatment gave essentially the same results.

Hospitalization Endpoints

There was a statistically significant difference between groups with respect to all-cause hospitalization, with 15.1% of the ziprasidone group and 10.9% of the olanzapine group requiring hospital care during the course of observation (Table 3). The primary intent-to-treat analyses showed a greater risk of all-cause hospitalization for the ziprasidone group compared with the olanzapine group (relative risk=1.39, 95% CI=1.29–1.50); results of the secondary analysis based on person-time on assigned treatment analyses were consistent (relative risk=1.57, 95% CI=1.44–1.72). In the primary intent-to-treat analyses, no differences were observed between the ziprasidone and olanzapine groups with respect to other secondary endpoints: hospitalization for myocardial infarction (relative risk=1.18, 95% CI=0.53–2.64); hospitalization for arrhythmia or arrhythmia reported during hospitalization for other reasons (relative risk=1.75, 95% CI=0.51–5.98); and hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis (relative risk=1.00, 95% CI=0.29–3.45). Secondary person-time on assigned treatment analyses showed consistent results.

| Hospitalization Endpointa | Ziprasidone Group | Olanzapine Group | Ratio | Total Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis: intent to treat | N=9,077 | N=9,077 | N=18,154 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | Risk Ratio | 95%CI | N | % | |

| All-caus | 1,370 | 15.09 | 987 | 10.87 | 1.39 | 1.29-1.50 | 2,357 | 12.98 |

| Arrhythmia | 7 | 0.08 | 4 | 0.04 | 1.75 | 0.51-5.98 | 11 | 0.06 |

| Myocardial infarction | 13 | 0.14 | 11 | 0.12 | 1.18 | 0.53-2.64 | 24 | 0.13 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 5 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.29-3.45 | 10 | 0.05 |

| Secondary analysis: person-time on assigned treatment | Person-Years=6,198 | Person-Years=6,902 | Person-Years=13,100 | |||||

| N | Rateb | N | Rateb | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | N | Rateb | |

| All-cause | 1,198 | 19.32 | 848 | 12.29 | 1.57 | 1.44-1.72 | 2,046 | 15.62 |

| Arrhythmia | 6 | 0.10 | 3 | 0.04 | 2.23 | 0.56-8.91 | 9 | 0.07 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 0.18 | 8 | 0.12 | 1.53 | 0.62-3.81 | 19 | 0.14 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 5 | 0.08 | 5 | 0.07 | 1.11 | 0.32-3.85 | 10 | 0.08 |

TABLE 3. One-Year Hospitalization Incidence, Primary and Secondary Analyses of Hospitalization Endpoints in the Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC), 2002-2007

A supplemental post hoc analysis was conducted by the Endpoint Committee chair to identify the reason for hospitalization among those hospitalizations previously not adjudicated as secondary endpoints (that is, not coded as a hospitalization for myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, or diabetic ketoacidosis) and to determine why a greater hospitalization incidence was observed among patients in the ziprasidone group relative to the olanzapine group. A larger proportion of patients in the ziprasidone group (11.1%) than in the olanzapine group (7.5%) experienced psychiatric hospitalizations (relative risk=1.48, 95% CI=1.35–1.62).

Although there were no significant differences between groups in the incidence of hospitalization due to arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, or diabetic ketoacidosis, a greater number of patients in the ziprasidone group than in the olanzapine group were hospitalized for arrhythmia or had arrhythmia reported during hospitalization for other reasons (seven and four, respectively, in the intent-to-treat analysis, and six and three, respectively, in the person-time on assigned treatment analysis). The cardiologist on the Endpoint Committee examined the documentation submitted for endpoint adjudication for these patients and found that there were no cases of tor-sade de pointes or ventricular arrhythmias in either group. Notably, in nine of these 11 cases, arrhythmia was not the primary reason for hospitalization but was observed during routine examinations conducted while the patient was hospitalized for other reasons; one patient was hospitalized for a psychiatric reason and seven for other medical reasons, and there was inadequate information on reason for hospitalization for one patient.

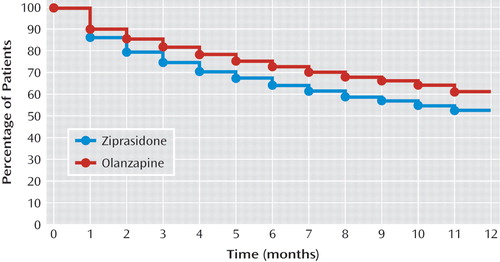

Time to Treatment Discontinuation

As shown in Figure 1, Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to study medication discontinuation showed that the proportions of patients remaining on study medication at 6 months and 12 months were significantly lower for zi-prasidone -compared with olanzapine. At 6 months, 64.6% of patients in the ziprasidone group and 73.2% of those in the olanzapine group remained on the study medication. At 12 months, 52.7% of patients in the ziprasidone group and 61.5% of those in the olanzapine group remained on the study medication.

a At 6 months, 64.6% of ziprasidone patients (95% CI=63.6–65.6) and 73.2% of olanzapine patients (95% CI=72.3–74.1) remained on study medication, and at 12 months, 52.7% of ziprasidone patients (95% CI=51.7–53.8) and 61.5% of olanzapine patients (95% CI=60.5–62.5) remained on study medication. For both time points, log-rank test p<0.001, Wilcoxon test p<0.001.

Discussion

ZODIAC is, to our knowledge, the largest prospective randomized study of patients with schizophrenia conducted to date. Previous data indicated that use of ziprasidone is associated with a modest prolongation of mean QTc. However, the impact of this risk on mortality was not known. The ZODIAC findings failed to show that, in real-world use, when compared with olanzapine, ziprasidone is associated with an increased risk of nonsuicide mortality, the study's primary outcome measure, in patients with schizophrenia; this study excludes with a high probability a relative risk larger than 1.39. Secondary outcome measures indicate that there was also no increased risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, sudden death, or suicide, although these were all rare events. These -conclusions are supported by the results of both the intent-to-treat analysis and the time on assigned treatment analysis. At the request of the FDA, a post hoc analysis of all mortality events was conducted to determine the incidence of sudden cardiac death and sudden death using ICD-10 codes. The results of these analyses were also consistent with those of the primary analyses.

The findings of a phase I study (12) conducted by Pfizer, Inc., that measured QTc interval prolongation comparing ziprasidone with several other antipsychotic drugs, all administered at high dosages, at steady-state, and with or without the addition of an inhibitor of ziprasidone metabolism, showed that the mean QTc prolongation was approximately 9–14 msec greater for ziprasidone than for several other antipsychotics and approximately 14 msec less than for thioridazine. Furthermore, in Pfizer's clinical trial development program, only two of 2,988 patients (0.06%) exposed to ziprasidone and one of 440 patients (0.23%) receiving placebo had a QTc interval ≥500 msec (Pfizer, Inc., data on file). At least three randomized controlled trials (15–17) involving a total of 1,192 patients (ziprasidone, N=589; olanzapine, N=603) have directly compared olanzapine and ziprasidone for acute episodes of psychosis in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. In these studies, no significant differences in QTc interval prolongation were observed between treatment arms. Olanzapine was associated with significantly greater increases in body weight and other metabolic measures.

In the present study, the difference in rate of all-cause hospitalization between the ziprasidone and olanzapine groups in a secondary analysis was explained by the difference in the number of psychiatric hospitalizations over the 1-year study. This difference is consistent with hospitalization rates observed in the 18-month Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, a pragmatic trial of patients with chronic schizophrenia (18), where 11% of patients treated with olanzapine and 18% of those treated with ziprasidone were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons. In contrast, the proportion of patients treated with ziprasidone who were hospitalized in the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST), a pragmatic trial of antipsychotic treatment in 498 first-episode schizophrenia patients (19), was lower than with olanzapine (7% compared with 20%), although the statistical significance of this difference was not reported.

The proportions of patients remaining on study medication at 6 months and 12 months were significantly lower for ziprasidone compared with olanzapine; the finding was consistent for psychiatric hospitalizations. Again this was consistent with results from CATIE (18), where time to discontinuation of treatment for any cause was significantly greater for patients treated with olanzapine than for those treated with the other agents included in the study. Similarly, in EUFEST (19), while reductions in symptom severity were comparable for all medication groups, patients treated with olanzapine tended to remain on treatment longer than those treated with other atypical antipsychotics.

Beyond differences in drug effects, other potential reasons for differences in hospitalization and treatment discontinuation may reflect nonequivalent dosing between the agents, despite the guidance provided by the label. For example, epidemiological studies show that ziprasidone is often prescribed at the lower end of the therapeutic range (20) and that discontinuation rates are lower at higher dosages (21). Furthermore, ziprasidone must be taken with food in order to be optimally absorbed (22), and it is unclear how often individuals with schizophrenia adhere to this administration requirement.

The results of the ZODIAC study show that hospitalization rates for diabetic ketoacidosis were low, occurring at an incidence of 0.1% in both the olanzapine and ziprasidone groups. Diabetic ketoacidosis is an acute metabolic complication of mostly type I diabetes and is relatively rare in type II diabetes. Incidence of hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis is not a surrogate for other metabolic abnormalities, such as new-onset type II diabetes. Because of ZODIAC's large simple trial design, diabetic ketoacidosis was chosen as a secondary metabolic endpoint because it is objectively measured and the severity of the event would typically result in hospitalization. Given that there was a similar low rate of reported medical history of type I diabetes (less than 3%) in both groups at baseline, the comparable 1-year incidence of hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis is within expectations.

The primary intent-to-treat analyses here are critical, as randomization maximizes the probability that the comparison is a fair one. However, especially for a safety study, the person-time in treatment analysis is also important, since it ensures that including unexposed time in the primary analysis did not mask a positive finding. The two analyses of course produced very similar results.

Although ZODIAC was very large with substantial statistical power, the study design did not allow evaluation of differences in the incidence of uncommon but important outcomes, such as torsade de pointes and sudden death. Instead, nonsuicide mortality was chosen as the primary endpoint since even a larger increase in an uncommon cause of death like torsade de pointes or sudden death could be counterbalanced by a small decrease in a more common cause of death, like atherosclerotic events. In addition, torsade de pointes would not be reliably detected as part of normal medical or psychiatric care because of its rarity and the absence of frequent ECG testing in the routine clinical settings in which ZODIAC was carried out. An aggregate measure like all-cause nonsuicide death was deemed to be the most important and appropriate outcome measure.

In summary, despite ziprasidone's known potential to increase QTc, this large study failed to show that ziprasi-done treatment is associated with an increased risk of nonsuicide mortality as compared with olanzapine in real-world use in patients with schizophrenia. Although small elevations in relative risk point estimates were found for some endpoints, there was no statistically significant elevation in the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, sudden death, or suicide; all-cause hospitalization was the only statistically significant result in this study. However, this study was not powered to examine the risk of an extremely rare event like torsade de pointes, which would have required a sample size that was orders of magnitude larger than the 18,154 patients examined in ZODIAC and would have required intensive and prolonged cardiac monitoring, which would have been at odds with the study's goal of adhering to routine clinical care.

1. : Excess mortality of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:502–508Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. : Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm County, Sweden. Schizophr Res 2000; 45:21–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68(suppl 4):8–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2007; 298:1794–1796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16 027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-1: First International Study of In-farct Survival Collaborative Group. Lancet 1986; 2:57–66Medline, Google Scholar

6. ;

7. : An assessment of the safety of pediatric ibuprofen: a practitioner-based randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1995; 273:929–933Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8.

9. : The case for practical clinical trials in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:836–846Link, Google Scholar

10. : QTc-interval abnormalities and psychotropic drug therapy in psychiatric patients. Lancet 2000; 355:1048–1052Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. : Cardiac arrest and ventricu-lar arrhythmia in patients taking antipsychotic drugs: cohort study using administrative data. BMJ 2002; 325:1070Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. : A randomized evaluation of the effects of six antipsychotic agents on QTc, in the absence and presence of metabolic inhibition. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:62–69Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. : The ziprasidone observational study of cardiac outcomes (ZODIAC): design and baseline subject characteristics. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:114–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14.

15. : Ran-domized, controlled, double-blind multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of ziprasidone and olanzapine in acutely ill -inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1837–1847; correction, 2005; 162:644Link, Google Scholar

16. : Olanzapine versus ziprasidone: results of a 28-week double-blind study in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1879–1887Link, Google Scholar

17. : A 24-week randomized study of olanzapine versus ziprasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in patients with prominent depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26:157–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. ;

19. ;

20. : Dose trends for second-generation antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 2009; 108:238–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. : Effect of ziprasidone dose on all-cause discontinuation rates in acute schizophrenia and schizoaffec-tive disorder: a post hoc analysis of 4 fixed-dose randomized clinical trials. Schizophr Res 2009; 111:39–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. : The impact of calories and fat content of meals on oral ziprasidone absorption: a randomized, open-label, crossover trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:58–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar