The Case for Practical Clinical Trials in Psychiatry

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Clinical trials in psychiatry frequently fail to maximize clinical utility for practicing clinicians, or, stated differently, available evidence is not perceived by clinicians (and other decision makers) as sufficiently relevant to clinical practice, thereby diluting its impact. To attain maximum clinical relevance and acceptability, researchers must conduct clinical trials designed to meet the needs of clinicians and others who are making decisions about patients’ care. The authors present the case for psychiatry’s adoption of the practical clinical trials model, which is widely used in research in other areas of medicine. METHOD: The authors outline the characteristics and scope of practical clinical trials, give examples of practical clinical trials, and discuss the challenges of using the practical clinical trials model in psychiatry, including issues of funding. RESULTS: Practical clinical trials, which are intended to provide generalizable answers to important clinical questions without bias, are characterized by eight key features: a straightforward clinically relevant question, a representative sample of patients and practice settings, sufficient power to identify modest clinically relevant effects, randomization to protect against bias, clinical uncertainty regarding the outcome of treatment at the patient level, assessment and treatment protocols that enact best clinical practices, simple and clinically relevant outcomes, and limited subject and investigator burden. CONCLUSIONS: To implement the practical clinical trials model in psychiatry will require stable funding for network construction and maintenance plus methodological innovation in governance and trial selection, assessment, treatment, data management, site management, and data analytic procedures.

It is widely acknowledged that the cultural shift toward evidence-based practice that is now under way in psychiatry (1, 2) requires that research be seen as integral rather than as separate from clinical practice (3). It is less widely acknowledged that using high-quality research evidence to guide clinical practice has as many implications for researchers as it does for clinicians (4, 5). Although substantial progress has been made in developing and testing new treatments, researchers for the most part have failed to design trials that maximize clinical utility for practicing clinicians and other decision makers, or, stated in terms of the contrary position, current best evidence often is not perceived by decision makers as relevant to clinical practice, thereby substantially diluting its impact (6). Moreover, clinical research in psychiatry is hobbled by high costs, lack of funding, regulatory burdens, fragmented infrastructure, slow results, and a shortage of qualified investigators and willing participants. To speed the translation of clinical research into medical practice, the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Elias Zerhouni, M.D., recently emphasized the need for practical clinical trials that are explicitly designed to aid decision makers who are faced with choices about patient care, whether at the doctor-patient level or the policy level (7). Accordingly, we make the case in this article that adopting the practical clinical trials model in psychiatry would have a positive public health impact in the care of mentally ill children, adolescents, and adults.

What Defines a Practical Clinical Trial?

More than a decade ago, Sir Richard Peto and colleagues coined the term “large, simple trial” (8) and, in so doing, emphasized that treatment outcomes studies should have sufficient power to identify modest clinically relevant effects, should employ randomization to protect against bias, and should be simple enough to make participation by patients and providers reasonable (9). More recently, Tunis et al. (5) described the defining features of a practical clinical trial; they are a study design that compares clinically important interventions, a diverse population of study participants representative of clinical practice, inclusion of a range of heterogeneous practice settings that are also representative of clinical practice, and measurement of a broad range of clinically relevant health outcomes. (Many consider the terms “practical clinical trial,” “pragmatic trial,” and “large, simple trial” to be interchangeable, because all three terminological conventions designate research that shares the primary goal of asking a question that, when answered, will inform persons who are making decisions about the care of patients. We use the appellation “practical clinical trial” because it is the emerging standard term for trials of this type.) Starting with the definition offered by Tunis et al. (5) and broadening it to include principles articulated by Peto and Baigent (9) and others (4, 10, 11), practical clinical trials can be characterized by eight defining principles:

| • | Questions must be simple, clinically relevant, and of substantial public health importance. Each practical clinical trial begins with a good question (12), for example, “Does a widely practicable treatment (or treatments) alter the major outcome(s) for a common mental disorder?” Not coincidentally, the more common and important the question, the easier it is to enroll subjects in a practical clinical trial. | ||||

| • | Practical clinical trials are performed in clinical practice settings. To enhance generalizability, a clinically representative (typically heterogeneous) sample of patients is recruited and treated in the clinical practice settings in which these patients are ordinarily found (13). | ||||

| • | Study power is sufficient to identify small to moderate effects. Although the size of a practical clinical trial depends on the question that needs to be answered, practical clinical trials are usually larger (and almost always simpler) relative to efficacy trials. For example, to identify clinically relevant if modest effects in a head-to-head trial of two active treatments, a practical clinical trial might allocate thousands of patients in hundreds of clinical centers to different treatments just as they are delivered in community settings (13). | ||||

| • | Randomization is the best defense against bias. Experimental manipulation of treatment assignment (e.g., randomization) is the best defense available against selection bias and confounding factors (14). Thus, in practical clinical trials, patients are randomly allocated to one or more active treatments and, depending on the question, to a control or active comparison condition or both. | ||||

| • | Randomization depends on clinical uncertainty. A good question is interesting only if it represents an important area of clinical uncertainty (2). As applied to a practical clinical trial, the uncertainty principle means that there is no substantial empirical basis for preferring one or another possible treatment (including study and nonstudy treatments) for a particular patient (9, 13). In turn, true uncertainty regarding what is the best treatment makes participation in research ethically reasonable with respect to the balance between benefit and harm and limits the possibility that real or apparent bias regarding participation will arise from the doctor-patient relationship. | ||||

| • | Outcomes are simple and clinically relevant. Outcomes are tracked by using unambiguous, readily detectable endpoints that reduce misclassification errors and simplify data collection (15, 16). A simple way of considering whether an outcome is appropriate for a practical clinical trial is by determining whether it 1) can easily be recognized by clinicians and/or patients and 2) reflects the construct of living longer, feeling better, avoiding unpleasant experiences such as having to go to the hospital, and spending less money. | ||||

| • | Assessments and treatments enact best clinical practice. To encourage findings that are clinically meaningful and that will transfer readily to clinical practice, practical clinical trials are characterized by simple, straightforward assessment and treatment methods typical of everyday good clinical practice (17). | ||||

| • | Subject and investigator burden associated with research goals are minimized. Although the degree of simplicity is dependent on the aims of the trial, practical clinical trials are completed in a timely fashion at relatively low cost by employing simple methods of protocol development, protocol dissemination, data gathering, and quality assurance (15, 16). In particular, the number and type of data elements (and, hence, subject and investigator burden) are kept small and straightforward so as not to discourage provider or patient participation and to maximize the number of subjects per dollar spent. | ||||

Scope of Practical Clinical Trials

Granting that the essential components of an outcomes study necessarily will vary as a function of the question being asked (18), practical clinical trials may be distinguished from efficacy trials, hybrid efficacy/effectiveness trials, dissemination trials, and practice research (Table 1).

In mental health outcomes research, the distinction is frequently made between efficacy and effectiveness trials (6), although Kraemer (19) cogently argued that efficacy and effectiveness represent anchor points at the end of a continuum rather than discrete categories. Randomized, controlled trials that focus on therapeutic efficacy ask the question: “Will a treatment work under ideal conditions?” With the industry-funded registration trial as the paradigmatic example, efficacy trials employ relatively homogeneous samples and intensive assessment strategies restricted to one or two primary outcomes. In so doing, efficacy trials explicitly maximize assay sensitivity for detecting a treatment signal on the primary outcome measure with the minimum sample size in the comparison of an active treatment with a control condition. Some efficacy trials also include an explanatory component, such as a pharmacokinetic substudy, designed to elucidate how or why a treatment works; usually, such substudies are accomplished at the cost of a much higher density of assessment. In contrast, effectiveness trials focus on gathering information of maximum interest to clinicians and other decision makers. In so doing, effectiveness studies, broadly conceptualized, employ heterogeneous samples that are recruited in a variety of practice settings and are assessed not only for primary outcomes but for a wide range of outcomes relevant to public health, such as comorbidity, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness (20, 21). The current generation of large comparative treatment trials funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (see, for example, reference 22) typically combines efficacy (usually involving intensive assessments) and effectiveness (usually a broad sampling frame) elements and thus occupies an intermediate position on the efficacy-to-effectiveness continuum.

Located at the far end of the effectiveness part of the spectrum, practical clinical trials ask, “Will a treatment do more good than harm under usual conditions of clinical practice?” Consequently, practical clinical trials are not well suited to outcomes studies with efficacy and explanatory aims, including treatment development studies (especially for novel treatments), dose-finding studies, studies of mechanisms of treatment action involving large numbers of mediator variables, or acute pharmacokinetic studies, some but not all of which necessarily precede practical clinical trials. Practical clinical trials are best suited to tests of the effectiveness of newly introduced treatments, compared to standard treatment; assessment of treatment additions to address partial response; research designs with many safety outcomes; population pharmacokinetic studies; and studies of events with relatively rare but important outcomes, such as death or rehospitalization.

In addition, because of enhanced sample representativeness and large sample sizes, which provide enhanced power to identify small effects, practical clinical trials are the ideal venue to investigate the question, “Which treatment for which patient with what subgrouping characteristics?” (5, 23). For example, practical clinical trials, unlike studies with smaller and less heterogeneous samples, typically have ample power to examine subgrouping variables, such as race, gender, age, severity, and pattern of comorbidity, alone and in combination. (One practical clinical trial of coronary reperfusion strategies spawned more than 80 papers, most of them involving subgrouping analyses [24].) Likewise, practical clinical trials that include genetic predictor variables that have low base rates will be especially valuable as pharmacogenetics assumes a more prominent role in designing clinical trials and in guiding the selection of treatments (25).

It is important to note that practical clinical trials as applied to safety outcomes constitute a major means to address the balance between benefit and harm in treatments as they are administered in clinical practice (26). The prevalence and relative risk of common adverse events can be estimated far more precisely in a 2,000-subject trial than in a 200-subject trial. Identifying the relative risk of uncommon (1 in 500 to 1,000) or rare (1 in 10,000) adverse events is possible only in the practical clinical trial setting. In this regard, adverse event reporting in practical clinical trials has been shown to enhance safety during the trial and to facilitate the role of data monitoring committees and institutional review boards confronted with multiple adverse event reports (27, 28).

Unlike dissemination research, which focuses on assessing the effectiveness of different dissemination strategies, practical clinical trials focus on comparing treatments rather than on the dissemination of those treatments. However, a key barrier to disseminating evidence-based treatments is the lack of development and testing of treatments in real-world practice settings (29). In this context, a preexisting practical clinical trial can facilitate dissemination of a new treatment through the development of new knowledge and of procedures that should prove readily transferable to clinical practice.

Lastly, although they take place in clinical practice settings, practical clinical trials are not the same as practice research, which is more powerful for profiling practice patterns than for asking and answering questions regarding the effectiveness of treatment (30, 31). On the other hand, it is undeniable that in fields that do practical clinical trials, the trials themselves change practice (15, 16). Those who participate in trials are more likely to practice according to the results of those trials, and the fact that a trial can be done in a typical practice situation greatly enhances the ability to disseminate the technology. Thus, practice research involving a practical clinical trial network typically focuses on understanding the practice settings to which the results of a practical clinical trial will generalize and the effects of participation in practical clinical trials on practitioners in those settings (5).

Examples of Practical Clinical Trials

Practical Clinical Trials in Medicine

Over the past several decades, the pressing need to understand the effect of widely practiced treatments on the major outcomes for common illnesses such as heart attack and stroke gave rise to increasingly large and sophisticated practical clinical trial networks in cardiovascular medicine (9). This process was greatly facilitated by network development and maintenance activities funded by NIH (32). As a result, practical clinical trials are now the norm in areas such as acute coronary syndrome and heart failure (10). For example, the Virtual Coordinating Center for Global Cardiovascular Research network has so far conducted 15 trials of thrombolytic agents with more than 150,000 enrolled patients at 3,000 sites in 50 countries (33). These practice-changing practical clinical trials have led to convincing improvements in coronary reperfusion and, more important, survival in patients with acute myocardial infarction (24).

In pediatric oncology, practical clinical trials conducted in the Children’s Oncology Group network have revolutionized the care of children with cancer (34). Illustrating the fact that practical clinical trials can and do take place in specialty clinics if that is where the patients are located, more than 95% of children with cancer in the United States are treated at the approximately 500 participating centers in the Children’s Oncology Group network, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute. The Children’s Oncology Group provides a national network of communication for researchers, care providers, and families of pediatric patients with malignant disease and conducts laboratory investigations and clinical trials of new treatments for cancer in infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. Cases seen in the network constitute, in effect, a national registry of nearly all childhood cancers in the United States. Because of the network’s broad coverage, more than half of American children with cancer are entered into at least one randomized Children’s Oncology Group trial, which in turn has led to dramatic improvement in pediatric cancer outcomes.

Practical clinical trials sometimes reveal that widely used, seemingly sensible clinical strategies that have been shown to work in small industry-funded registration trials can, in actual fact, be harmful when applied in real clinical settings. In a sobering and heuristically valuable example, the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial examined Class I antiarrhythmic drugs that had been shown in small efficacy trials to suppress ventricular extrasystoles in patients at increased risk of death after a heart attack (35). Intuitively, it seemed reasonable that a reduction in irregular heartbeats also should result in reduced mortality. However, the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial revealed that these drugs were associated with a 250% increase in short-term mortality, whereas newer Class III antiarrhythmic agents appeared to reduce mortality (36). The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial nicely illustrates how practical clinical trials can be useful in confirming that the results of small efficacy trials will translate (or will not translate, as the case may be) to real-world practice (37), especially when the initial trials involved surrogate markers for relatively rare outcomes such as mortality.

Practical Clinical Trials in Psychiatry

Practical clinical trials are just beginning to occur in psychiatry (1, 38). Projects illustrating recent progress in implementing practical clinical trials in the mental health field include the British Bipolar Affective Disorder: Lithium Anticonvulsant Evaluation trial involving adults with bipolar disorder (2); the industry-funded International Suicide Prevention Trial in schizophrenia (39); the NIMH-funded practical clinical trials in adults with depression, bipolar disorder, psychosis, and Alzheimer’s disease (40–43); and the NIMH-funded Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network (38).

Funded by the Stanley Foundation and the British Medical Research Council, the Bipolar Affective Disorder: Lithium Anticonvulsant Evaluation trial addresses the question, “In adult patients with bipolar illness, is lithium, sodium valproate, or a combination of the two more effective in reducing the risk of further episodes of mania or depression and in improving long-term effects on mood and more tolerable in terms of side effects?” The trial will recruit thousands of patients at 54 centers who will be randomly assigned to best-practice active treatments and assessed with simple, clinically relevant categorical and dimensional outcomes measures (2).

The recently completed International Suicide Prevention Trial compared the effects of clozapine and olanzapine in 980 adults with schizophrenia at high risk for suicide at 56 sites in 11 countries (44). As is typical of a practical clinical trial, the study included freedom to augment these treatments as needed, blind ratings in which suicide was the primary outcome, and equivalent clinical contact for the two treatment groups. Clozapine proved superior to olanzapine in reducing suicidality. Although it is too soon to evaluate the impact of the International Suicide Prevention Trial on clinical practice, the investigators suggested that clozapine should be considered for all patients with schizophrenia at high risk for suicide (44).

NIMH recently funded three large practical clinical trials designed to address questions of major public health relevance that emerged from but were not answered by earlier industry-funded efficacy trials: 1) Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression, which compares active treatments and treatment strategies in adults with depression (40); 2) Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder, which focuses on the pharmacological and psychosocial treatment of bipolar illness (41); and 3) Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness, which contrasts various atypical antipsychotics as treatments for psychosis or for Alzheimer’s disease (42, 43). These trials have innovative experimental designs—including an equipoise-stratified design in Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (45) and an outcomes-based rerandomization scheme in Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (46)—and are much larger than any study previously attempted in psychiatry. They pioneer the construction of the kind of networks that are essential for making practical clinical trials a routine part of psychiatric practice.

A partnership between researchers at Duke University and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the NIMH-funded Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network is an investigator-initiated proof-of-concept effort to establish a practical clinical trial network in pediatric psychiatry (38). Guided in the selection of specific questions by network members and expert advisory panels, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network will focus on two critically important clinical issues: 1) obtaining evidence from randomized trials of the effectiveness of widely used but understudied combined drug treatments and 2) investigating the short- and long-term safety of pharmacotherapy. With 200–400 child and adolescent psychiatrists each participating in two or three practical clinical trials at any one time, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network promises to advance both the evidence base and the research capacity of child and adolescent psychiatry.

Challenges in Adopting Practical Clinical Trials in Psychiatry

Network Construction and Maintenance

Practical clinical trials typically flourish in networks that are developed and maintained by research centers in productive partnership with clinical and administrative decision makers in federal, community, and academic settings (5, 37, 47). No stably funded practical clinical trial infrastructure currently exists in psychiatry—the current practical clinical trials in psychiatry (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression, Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder, Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness, and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network) will sunset if their funding is not renewed. Thus, the development of a stable practical clinical trial infrastructure, including establishing a coordinating center or centers, remains a necessary step toward the implementation of the practical clinical trials model in mental health care. A coordinating infrastructure with access to researchers and other individuals with the skills and equipment required to conduct a practical clinical trial is necessary 1) to recruit and sustain a broad-based network of clinical sites representative of current practice and service systems (site development); 2) to institute the mix of financial, practical (e.g., continuing medical education), and altruistic incentives that makes ongoing network participation reasonable and desirable; 3) to develop trial-independent and trial-dependent clinical research training for site investigators; and 4) to characterize the practice patterns and factors that affect clinical decision making, treatment provision, and conformance with evidence-based treatment recommendations within each site. It is important to note that to cover the practice landscape in which mentally ill patients are found and to model rational triage strategies, it will be necessary to extend practical clinical trial networks to specialty clinics (which, by analogy to specialty cancer clinics, might be appropriate for rare conditions such as schizophrenia or complex tic disorders) and to community practice settings (for more common illnesses, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or major depression). Other important aspects of network coordination include the development of systems for data management and the provision of analytic and dissemination infrastructures. Finally, initiatives to conduct practical clinical trials in other areas of medicine have been successful because network participants were trained in network protocols during residency and continued to participate after they began clinical practice. Hence, seamless integration of practical clinical trials into training programs (as will be done in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network [38]) is of paramount importance if practical clinical trials are to be widely implemented in mental health delivery systems.

Developing Questions That Are Directly Relevant to Clinical Practice

Although much progress has been made, clinical practice in psychiatry remains far from being evidence based (48), with heterogeneity in practice predicting heterogeneity in quality of care (49, 50). In treatment of children, for example, there has been a rapid shift from a single-drug standard toward complex multidrug treatment regimens (51) for which scientific support is completely lacking (52). These gaps in the research literature, which can be identified by examining postmarketing pharmacoepidemiologic studies (53) and findings from practice research (30, 31) and by perusing expert-driven treatment guidelines (17, 54), contribute both to the rationale and, by guiding the choice of questions, to the method for prioritizing a practical clinical trial research agenda. In addition, because physicians participating in practical clinical trials are themselves interested in securing straightforward answers to a large number of highly relevant clinical questions, vetting questions and protocols through the network members is an effective way to prioritize practical clinical trials and also serves a network maintenance function by enhancing recruitment of patients into clinical trials.

Using Placebo Controls, Active Comparators, and Blinding

As with efficacy studies, the choice of an experimental design in a practical clinical trial depends on the theoretical and practical aims of the trial (55). When the primary purpose of a trial is to secure an unbiased evaluation of whether a treatment signal is present, an inactive control condition—typically pill placebo in pharmacotherapy trials—maximizes the so-called assay sensitivity of the experiment. Two settings in which a placebo condition would be considered for a practical clinical trial are: 1) if one or more treatments have never been shown to be superior to an inactive control treatment or 2) if it is unreasonable to infer that the results of prior randomized clinical trials of an active treatment, compared with placebo, will be replicated if tested in the same patient population and if a true tie is unacceptable for this setting. Although the optimal time for a placebo-controlled trial is early in the treatment development cycle, before widespread belief in the clinical effectiveness of a treatment accrues, a great deal of the evidence clinicians need to practice effectively involves comparisons of active treatments and treatment addition strategies targeting partial response. This requirement makes placebo-controlled practical clinical trials appropriate long after early-phase efficacy studies have been completed.

Despite the fact that some investigators believe that a null result in a trial with two active treatments cannot be interpreted in the absence of an inactive control condition, practical clinical trials without a concurrent placebo arm are relatively common. For example, if both active treatments have shown unequivocal superiority against placebo, then a practical clinical trial without a concurrent placebo control condition is generally thought reasonable, especially if use of placebo can be said to violate the principle of therapeutic uncertainty (56). Even when this standard is not met, some advocates of practical clinical trials would argue that, unless a newer treatment has substantial advantages with respect to adverse events, user friendliness, or cost, if it cannot beat a proven treatment in a practical clinical trial powered for a small effect size, “Who needs it?”

Finally, in a practical clinical trial with an active comparator or comparators but no placebo group, the investigator must decide whether masking (blinding treatments to eliminate observer bias) is essential to the study aims. Observer bias occurs when information held by the observer influences the way he or she interprets and scores a primary outcome. In clinical practice, knowledge of treatment assignment is part of the ecological validity of the outcome (because patients know the nature of their treatment assignment) and, moreover, is consistent with the uncertainty principle for the study treatments. Thus, openly assigning patients to treatment does not necessarily detract from (and, in fact, may enhance) the robustness of a practical clinical trial.

Using Interventions That Match Best Clinical Practice

As in efficacy trials, treatment protocols in a practical clinical trial must specify the treatment(s) to be used; titration of medications for subjects through the use of fixed, flexible, or a combination of fixed and flexible dosing methods; range of starting doses; administration schedule; selection of brand-name or generic drugs; choice of rating forms and symptoms rated during titration and how this information will be used; adverse event monitoring and its effect on dosing strategy; and procedures for managing emergencies. In this regard, tensions exist between adherence (how well the standardized treatment protocol is followed) and competence (how well the treatment is done clinically); between tailoring treatment to the needs of the patient and using uniform, manualized, explicitly specified intervention(s); and between the desire for site flexibility and efficiency and the need for a common protocol that minimizes the potential for between-site drift in protocol implementation. To facilitate protocol acceptance and compliance, practical clinical trials evaluate these tensions through the perspective of the practicing clinician, especially when a standard of care is widely acknowledged. Thus, practical clinical trial researchers must work collaboratively with network clinicians to develop short, user-friendly protocols and manuals that are empirically grounded and clinically meaningful in order to maximize the generalizability of best practices to the community of psychiatrists caring for patients.

Developing Simple, Ecologically Valid Diagnostic and Endpoint Assessments

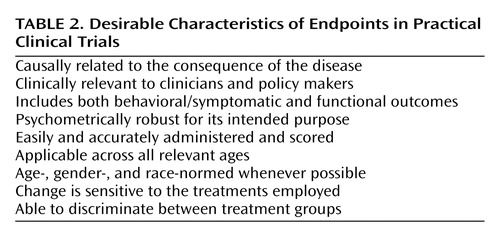

Although well-justified exceptions exist (see reference 57 for an explanatory aim linked to an important functional outcome), practical clinical trials generally eschew complex and time-consuming assessments designed to satisfy explanatory aims in favor of assessment strategies that are intended to be widely applicable to real-world practice settings (4). Specifically, practical clinical trials use unambiguous, readily detectable, ecologically valid diagnostic strategies and endpoints that reduce misclassification errors and simplify data collection, thereby easing the burden of participation on patients and clinicians (Table 2). For example, a practical clinical trial end-of-treatment assessment might use a DSM-IV diagnostic checklist, one or two short self-report scales, a checklist of functional outcomes, and summary clinician-rated measures, such as a Clinical Global Impression score, that together might take all of 30 minutes to complete in the context of a routine office visit. For practical clinical trials, the central question is whether these simplified assessments, which by definition should transfer readily to clinical practice, yield reliable and valid inferences regarding the outcome of treatment.

The most vexing objection aimed at the practical clinical trials model as applied to psychiatry is whether endpoints can be found that match this ideal (1, 4, 58). Practical clinical trials in psychiatry have been criticized because, unlike cancer and cardiovascular randomized clinical trials, which use “hard,” dramatic, and unmistakable events (such as mortality) as endpoints, psychiatry trials rely on “soft” behavioral/symptomatic outcomes (4). Although it is true that psychiatric outcomes are subject to greater measurement error, relative to, for example, mortality as an outcome, psychiatric research does have some readily available hard endpoints, such as predefined study rescue procedures, suicide attempts, treatment switching, hospitalization, school failure or truancy, job loss, or even dropping out of the trial itself. Furthermore, it is possible to overestimate the “hardness” of both medical and psychiatric endpoints—consider, for example, the misclassification of myocardial infarction in cardiology trials (59) or the difficulty of suicide adjudication in the International Suicide Prevention Trial (44)—and to underestimate the proven utility of “softer” endpoints, such as quality of life (60), global outcomes, or scores on psychometrically robust rating scales (see, for example, references 61, 62).

Even granting that measures used in a practical clinical trial are reliable and valid, critics argue that site differences and clinician-to-clinician variability in diagnostic and endpoint assessments could conceivably attenuate the ability to identify between-group differences (63). Fortunately, one of the strengths of the practical clinical trials model is the small standard errors associated with the large sample sizes (2). Put differently, the estimate of the true population mean almost certainly will be more precise in a 2,000-subject parallel-group practical clinical trial than in a meta-analysis of ten underpowered 200-subject efficacy trials. This feature is one of the reasons why most designers of practical clinical trials would prefer to collect a clinical global improvement score in hundreds or thousands of patients rather than to measure 100 variables in a small group of patients. Likewise, the ecological validity, and thus generalizability, of the result as it would translate to clinical practice depends on reproducing the variability present in best clinical practice. In this context, a large study “N,” coupled with assessment strategies that capture the normal outcome of treatment, can be seen as an essential ingredient, not a weakness, of the practical clinical trial approach.

Using Quality Assurance Procedures That Reflect Good Clinical Practice

The generalizability of a practical clinical trial is determined in large part by the extent to which the trial patients and the practice settings in which they are found resemble the patients and practice settings to which the results of the study are intended to apply. Filters—whether related to inclusion or exclusion criteria or to some aspect of subject or investigator burden associated with quality assurance procedures—attenuate this relationship by selectively limiting study enrollment or encouraging dropout. Complex quality assurance procedures, such as intensive face-to-face training procedures, site visits, and real-time reliability checks, are impossible in a practical clinical trial. Instead, quality assurance in a practical clinical trial typically focuses on consistent implementation and documentation of compliance with assessment and treatment protocols by using adherence checklists. In this feature, practical clinical trials follow the approach of Peto and Baigent (9) with respect to the implementation of quality assurance:

Requirements for large amounts of defensive documentation imposed on trials by well intentioned guidelines on good clinical practice (or good research practice) or excessive audits may, paradoxically, substantially reduce the reliability with which therapeutic questions are answered, if their indirect effect is to make randomized trials smaller or even to prevent them starting.

Developing Innovative Methods

For the simple reason that practical clinical trials are new to psychiatry, it will be necessary to develop novel methods of sample recruitment and retention, new measures to broaden assessment of the effect of interventions at the individual and system levels, innovative research designs, innovative data entry and database management techniques, and new statistical analytic methods. Hence, practical clinical trials in psychiatry inevitably will encourage collaboration of methodologists from diverse academic backgrounds, including epidemiology, statistics, behavioral and social science, engineering, computer science, and public policy. Because longitudinal data are common in psychiatric research, particular attention must be paid to the application of long-time-frame random regression, pattern mixture, and propensity scoring techniques for handling missing data and other sources of loss of randomization; survival analysis models; power and sample size considerations; and concerns regarding multiple comparisons and multiple outcomes across many publications. In turn, attendant methodological innovation will increase the relevance of research findings for community stakeholders such as payers and public policy makers, as well as drive changes in methods for efficacy and hybrid efficacy/effectiveness trials.

Who Should Fund Practical Clinical Trials?

Practical clinical trials in psychiatry are in short supply partly because the primary funding sources for clinical research—NIMH, other NIH institutes addressing mental illness, and the pharmaceutical industry—have not until very recently provided financial support for individual practical clinical trials or a practical clinical trial network infrastructure. Clearly, an expanded role for practical clinical trials within the mental health care delivery system will depend on a substantial increase in public and private funding. For this increase to occur, clinical and health policy decision makers will need to make the funding of practical clinical trials a priority, including funding for infrastructure development, for studies as distinct from the infrastructure, for mechanisms of priority setting, and for methodological innovation. Although such a step is consistent with the 1999 recommendations of the National Advisory Mental Health Council (64), until recently no well-established funding mechanism for network studies has existed in the NIMH portfolio. There is an urgent need to further develop NIH/NIMH funding mechanisms specific to supporting networks of independent, skilled clinicians and researchers who are interested in sponsoring and performing practical clinical trials, especially when the potential profits are low but the scientific interest is high. In this context, it remains to be seen to what extent the recently published NIH “roadmap” (7) will spur a reengineered psychiatric research enterprise that emphasizes practical clinical trials conducted through a partnership between NIMH, academic institutions, consumers, and community-based mental health care systems. If the transition to practical clinical trials is successful, the return on investment should be high. In comparison to the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (22), which with 439 subjects will take 8 years and $17 million to complete, it is estimated that the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network, with 400 child and adolescent psychiatrists each monitoring four to six subjects, will be able to complete a 1,600-subject trial from question to first manuscript in less than 2 years at a per trial cost (exclusive of the network’s infrastructure) of less than $2 million.

In most practical clinical trials, the cost of research but not the cost of patient care is borne by the network. This fact raises both practical and legal issues, because there is controversy in the managed care environment about whether insurance plans will even allow, much less cover, the cost of care for patients enrolled in practical clinical trials. The NIH position is clear. As outlined in the Code of Federal Regulations section that defines NIH policy on the determination and reimbursement of research patient care costs under grants (45 CFR 74, Appendix E),

The patient and/or third-party insurance usually will provide for reimbursement of charges for “usual patient care” as opposed to non-reimbursement for those charges generated solely because of participation in a research protocol.

NIMH has not articulated a formal position on this question, but clinical care in the three large trials mentioned earlier, including most medications, is routinely reimbursed under standard insurance mechanisms. However, blinded, placebo-controlled drugs and specific research assessments (in contrast to clinical assessments) typically are paid for by research funds. It would therefore appear that providers in practical clinical trials are legally able to bill under standard insurance mechanisms, and, where blinding and use of placebo are not an issue, patients will be able to use standard prescription benefits to purchase medication. In addition, because no additional charges will be added to the cost of usual care as a function of participating in research, it is anticipated that there will be no economic or legal constraints to adding research procedures to standard clinical care.

Clinical psychopharmacology has been and likely will remain heavily influenced, if not dominated by, the pharmaceutical industry, especially for compounds early in the product development sequence. Industry funding for clinical trials is many times larger than NIH (extramural, including NIMH) funding: $4.1 billion, compared to $850 million in 2000, with only 10% of industry funds devoted to phase-IV trials (65). Because most if not all practical clinical trials would be classified as phase-IIIb or phase-IV trials, these trials would be disadvantaged with respect to potential funding either by industry or NIH. It is important to note that although industry-sponsored research is critical to new product development, its emphasis is on meeting U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory requirements and on obtaining expanded marketing claims, not on evaluating the effectiveness of products as used in the general population. As a result, industry-sponsored research often fails to address broad public health needs or the needs of individual practitioners seeking to make good clinical decisions for individual patients. This shortcoming of industry-sponsored research is especially pertinent for decisions regarding risk, use of adjunctive treatments to improve partial response, maintenance and discontinuation of treatment, and transportability of treatments from the research to the clinical setting.

Although a compelling scientific argument can be made for practical clinical trials funded by industry (fewer negative findings and more definitive answers to safety questions, among other reasons), it is unlikely, although not inevitably so, that pharmaceutical companies will pursue a practical clinical trials agenda in psychiatry if doing so will, in their perception, put profits at risk, even when the answers would be of substantial public health importance. Particularly when comparing newer to older off-patent treatments, the risk of an adverse outcome (including a true tie) would be too great. Hence, in contrast to other areas of medicine where practical clinical trials are the standard for phase-III trials (10), industry-funded practical clinical trials in psychiatry in the short-term future will likely emphasize treatment addition studies—as in the epilepsy studies model in which a newer drug is added to an older compound to incrementally improve overall outcome (66)—if only because the requisite subject numbers are more readily available in the practical clinical trial framework. However, it may be worthwhile to point out that a more mature view of the role of regulatory agencies in “anticipating the market” would be to mandate that practical clinical trials should be done from the very beginning for psychotropic medications that will have widespread dissemination to the public. If the clinicians who prescribe these drugs would demand practical outcomes trials and, not incidentally, insist on the ethical obligation to make the results of human experiments public, the pharmaceutical companies would be more likely to do practical clinical trials and to publish the results.

Summary and Conclusions

After decades of industry-sponsored efficacy studies, psychiatry appears primed to follow the rest of medicine in moving toward practical clinical trials that seek to identify clinically relevant treatment outcomes of substantial public health importance. Such trials are necessary to evaluate clinically important interventions in a diverse population of study participants recruited from heterogeneous practice settings by using outcomes data that cover a broad range of ecologically valid health indicators (9). Without practical clinical trials, the heterogeneity in practice that yields regrettable heterogeneity in quality of care will continue unopposed because of the all-too-limited and often irrelevant evidence base (50). To implement the practical clinical trials model in psychiatry will require network construction and maintenance, procedures for matching trial aims to clinical practice requirements, best-clinical-practice assessments and treatments, selection of appropriate control or comparison conditions, simple yet reliable diagnoses and endpoints, feasible quality assurance procedures, and innovative data collection, management, and analytic procedures. For these developments to happen, a range of stakeholders, including NIMH, FDA, the clinical research community, and consumer advocacy groups, must work together to make practical clinical trials in psychiatry a priority.

|

|

Received Nov. 21, 2003; revisions received April 19 and June 12, 2004; accepted July 8, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. March, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke Child and Family Study Center, 718 Rutherford St., Durham, NC 27705; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants 1 K24 MH-01557 and 1 P30 MH-66386 and by NIMH contract 98-DS-0008 to Dr. March.

1. Geddes J, Carney S: Recent advances in evidence-based psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:403–406Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Geddes J, Goodwin G: Bipolar disorder: clinical uncertainty, evidence-based medicine and large-scale randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2001; 41:S191-S194Google Scholar

3. Geddes J, Reynolds S, Streiner D, Szatmari P: Evidence based practice in mental health (editorial). Br Med J 1997; 315:1483–1484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hotopf M, Churchill R, Lewis G: Pragmatic randomised controlled trials in psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:217–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM: Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA 2003; 290:1624–1632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Norquist GS, Magruder KM: Views from funding agencies: National Institute of Mental Health. Med Care 1998; 36:1306–1308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Zerhouni E: Medicine: the NIH roadmap. Science 2003; 302:63–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Peto R, Collins R, Gray R: Large-scale randomized evidence: large, simple trials and overviews of trials. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993; 703:314–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Peto R, Baigent C: Trials: the next 50 years: large scale randomised evidence of moderate benefits (editorial). Br Med J 1998; 317:1170–1171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Califf RM, Woodlief LH: Pragmatic and mechanistic trials. Eur Heart J 1997; 18:367–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Helms PJ: “Real world” pragmatic clinical trials: what are they and what do they tell us? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2002; 13:4–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Guyatt GH, Rennie D: Users’ guides to the medical literature (editorial). JAMA 1993; 270:2096–2097Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Baigent C: The need for large-scale randomized evidence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 43:349–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Peto R, Collins R, Gray R: Large-scale randomized evidence: large, simple trials and overviews of trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1995; 48:23–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Califf RM, DeMets DL: Principles from clinical trials relevant to clinical practice, part I. Circulation 2002; 106:1015–1021Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Califf RM, DeMets DL: Principles from clinical trials relevant to clinical practice, part II. Circulation 2002; 106:1172–1175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Geddes JR, Harrison PJ: Closing the gap between research and practice. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:220–225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Nathan PE, Stuart SP, Dolan SL: Research on psychotherapy efficacy and effectiveness: between Scylla and Charybdis? Psychol Bull 2000; 126:964–981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kraemer HC: Pitfalls of multisite randomized clinical trials of efficacy and effectiveness. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:533–541Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K: Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:1190–1197Link, Google Scholar

21. Burns BJ: Children and evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003; 26:955–970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study Team: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): rationale, design, and methods. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:531–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS: Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:877–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Califf RM: The GUSTO trial and the open artery theory. Eur Heart J 1997; 18(suppl F):F2-F10Google Scholar

25. Cardon LR, Idury RM, Harris TJ, Witte JS, Elston RC: Testing drug response in the presence of genetic information: sampling issues for clinical trials. Pharmacogenetics 2000; 10:503–510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Morse MA, Califf RM, Sugarman J: Monitoring and ensuring safety during clinical research. JAMA 2001; 285:1201–1205Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Califf RM, Lee KL: Data and safety monitoring committees: philosophy and practice. Am Heart J 2001; 141:154–155Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Califf RM, Ellenberg SS: Statistical approaches and policies for the operations of Data and Safety Monitoring Committees. Am Heart J 2001; 141:301–305Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Weisz JR: Agenda for child and adolescent psychotherapy research: on the need to put science into practice (comment). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:837–838Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, West JC, McIntyre JS: Practice-based research in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1199–1208Link, Google Scholar

31. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanielian TL, Johnson JL, West JC, Pettit AR, Marcus SC, Kessler RC, McIntyre JS: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997: findings from the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:441–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Zerhouni EA: NIH Director Elias A Zerhouni, MD, reflects on agency’s challenges, priorities: interview by Catherine D DeAngelis. JAMA 2003; 289:1492–1493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Topol EJ, Califf RM, Van de Werf F, Simoons M, Hampton J, Lee KL, White H, Simes J, Armstrong PW (Virtual Coordinating Center for Global Collaborative Cardiovascular Research [VIGOUR] Group): Perspectives on large-scale cardiovascular clinical trials for the new millennium. Circulation 1997; 95:1072–1082Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Bleyer WA: The US pediatric cancer clinical trials programmes: international implications and the way forward. Eur J Cancer 1997; 33:1439–1447Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Greene HL, Roden DM, Katz RJ, Woosley RL, Salerno DM, Henthorn RW: The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial: first CAST…then CAST-II. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19:894–898Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Yap YG, Camm AJ: Lessons from antiarrhythmic trials involving class III antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Cardiol 1999; 84(9A):83R-89RGoogle Scholar

37. DeMets DL, Califf RM: Lessons learned from recent cardiovascular clinical trials, part I. Circulation 2002; 106:746–751Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. March J, Silva S, Compton S, Anthony G, Deveaugh-Geiss J, Califf RM, Krishnan KR: The Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network (CAPTN). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:515–518Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Meltzer HY: Suicide and schizophrenia: clozapine and the InterSePT study. International Clozaril/Leponex Suicide Prevention Trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 12):47–50Google Scholar

40. Rush AJ, Trivedi M, Fava M: Depression, IV: STAR*D treatment trial for depression (image, neuro). Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:237Link, Google Scholar

41. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, Bauer M, Miklowitz D, Wisniewski SR, Lavori P, Lebowitz B, Rudorfer M, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Bowden C, Ketter T, Marangell L, Calabrese J, Kupfer D, Rosenbaum JF: Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:1028–1042Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Schneider LS, Ismail MS, Dagerman K, Davis S, Olin J, McManus D, Pfeiffer E, Ryan JM, Sultzer DL, Tariot PN: Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE): Alzheimer’s disease trial. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:57–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Byerly MJ, Glick ID, Canive JM, McGee MF, Simpson GM, Stevens MC, Lieberman JA: The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:15–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, Altamura AC, Anand R, Bertoldi A, Bourgeois M, Chouinard G, Islam MZ, Kane J, Krishnan R, Lindenmayer JP, Potkin S: Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:82–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Alpert J, Fava M, Kupfer DJ, Nierenberg A, Quitkin FM, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Trivedi M: Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: equipoise-stratified randomization. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:792–801Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Davis SM, Koch GG, Davis CE, LaVange LM: Statistical approaches to effectiveness measurement and outcome-driven re-randomizations in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) studies. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:73–80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Sung NS, Crowley WF Jr, Genel M, Salber P, Sandy L, Sherwood LM, Johnson SB, Catanese V, Tilson H, Getz K, Larson EL, Scheinberg D, Reece EA, Slavkin H, Dobs A, Grebb J, Martinez RA, Korn A, Rimoin D: Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA 2003; 289:1278–1287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Norquist G, Hyman SE: Advances in understanding and treating mental illness: implications for policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999; 18:32–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Birkmeyer JD, Bredenberg CE, Fisher ES: Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population: trial hospitals, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA 1998; 279:1278–1281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Szatmari P: Evidence-based child psychiatry and the two solitudes. Evid Based Ment Health 1999; 2:6–7Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Safer DJ: Changing patterns of psychotropic medications prescribed by child psychiatrists in the 1990s. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997; 7:267–274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Magder LS, Gardner JF, Zarin DA: Psychotherapeutic medication patterns for youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999; 153:1257–1263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Vitiello B, Hoagwood K: Pediatric pharmacoepidemiology: clinical applications and research priorities in children’s mental health. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997; 7:287–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Frances A, Kahn D, Carpenter D, Frances C, Docherty J: A new method of developing expert consensus practice guidelines. Am J Manag Care 1998; 4:1023–1029Medline, Google Scholar

55. Al-Khatib SM, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, Alexander JH, McCrory DC, Sugarman J: Medicine: placebo-controls in short-term clinical trials of hypertension. Science 2001; 292:2013–2015Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Streiner DL: Placebo-controlled trials: when are they needed? Schizophr Res 1999; 35:201–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Keefe RS, Mohs RC, Bilder RM, Harvey PD, Green MF, Meltzer HY, Gold JM, Sano M: Neurocognitive assessment in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project schizophrenia trial: development, methodology, and rationale. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:45–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Boyle MH, Jadad AR: Lessons from large trials: the MTA study as a model for evaluating the treatment of childhood psychiatric disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1999; 44:991–998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Mahaffey KW, Roe MT, Dyke CK, Newby LK, Kleiman NS, Connolly P, Berdan LG, Sparapani R, Lee KL, Armstrong PW, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Harrington RA: Misreporting of myocardial infarction end points: results of adjudication by a central clinical events committee in the PARAGON-B trial: second platelet IIb/IIIa antagonist for the reduction of acute coronary syndrome events in a global organization network trial. Am Heart J 2002; 143:242–248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Dorman P, Dennis M, Sandercock P (United Kingdom Collaborators in the International Stroke Trial): Are the modified “simple questions” a valid and reliable measure of health related quality of life after stroke? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:487–493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Nieri JM, Haak DC: Assessing clinical and functional outcomes in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:33–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Potkin SG, Alphs L, Hsu C, Krishnan KR, Anand R, Young FK, Meltzer H, Green A: Predicting suicidal risk in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients in a prospective two-year trial. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:444–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Barer DH, Ebrahim SB, Mitchell JR: The pragmatic approach to stroke trial design: stroke register, pilot trial, assessment of neurological then functional outcome. Neuroepidemiology 1988; 7:1–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Bridging Science and Service: A Report by the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

65. Getz K, Zisson S: Clinical grants market decelerates. CenterWatch, Oct 2003, pp 4–5Google Scholar

66. Perucca E, Tomson T: Monotherapy trials with the new antiepileptic drugs: study designs, practical relevance and ethical implications. Epilepsy Res 1999; 33:247–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar