Problems in Psychotherapy With Suicidal Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors studied recurrent problems in psychotherapy with suicidal patients by examining the cases of patients who died by suicide while receiving open-ended psychotherapy and medication. METHOD: Therapists for 36 patients who died by suicide while in treatment filled out clinical, medication, and psychological questionnaires and wrote detailed case narratives. They then presented their cases at an all-day workshop, and critical problems were identified in the cases. RESULTS: Six recurrent problem areas were identified: poor communication with another therapist involved in the case, permitting patients or relatives to control the therapy, avoidance of issues related to sexuality, ineffective or coercive actions resulting from the therapist’s anxieties about a patient’s potential suicide, not recognizing the meaning of the patient’s communications, and untreated or undertreated symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: These cases illuminate common problems therapists face in working with suicidal patients and highlight an unmet need for education of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals who work with this population.

Considerable evidence points to the complexity of the psychotherapeutic treatment of suicidal patients (1–4). A number of structured protocols have been developed to treat suicidality, including cognitive behavior problem-solving therapy (5–8), dialectical behavior therapy (1, 9, 10), time-limited interpersonal psychotherapy (11), and brief psychodynamic psychotherapy (12). Although some evidence exists for the efficacy of such protocols for selected patient groups, in our experience of supervising, consulting with, and studying clinicians who treat suicidal patients, we have found that most clinicians employ a relatively open-ended, eclectic psychotherapeutic approach that incorporates cognitive behavior and interpersonal techniques and varying degrees of reliance on psychodynamic principles. Consistent with results reported in recent clinical trials (13), such clinicians generally use a combination of open-ended psychotherapy and psychotropic medications in treating seriously disturbed suicidal patients. In contrast to the efficacy of structured approaches, the efficacy of such treatment has not been scrutinized.

In an ongoing project, we studied the cases of 36 patients who died by suicide while receiving open-ended psychotherapy and medication. The analysis of these cases offered an opportunity to identify retrospectively a number of recurrent problems that occurred in these therapies.

Method

The cases were obtained from therapists who were recruited through colleagues, mailings, journal notices, and website announcements. Project procedures were explained to the therapists, and the therapists provided informed consent for participation in the study. Each therapist completed semistructured questionnaires dealing with the patient’s background, clinical history, medication history, affective states, and psychodynamic phenomena related to the suicide. An additional questionnaire was used to elicit the therapist’s reactions to the suicide and perceptions of key problems in the patient’s treatment. Therapists also prepared detailed case narratives in which the patient’s identifying characteristics were disguised. Some sections of the narratives focused on the treatment process. Two therapists at a time then met with project investigators in an all-day workshop to review and discuss the cases.

Therapist Participants

Of the 36 therapists who participated, 25 were male and 11 were female. Two therapists contributed two cases each, and in two cases where the patient was jointly or simultaneously treated by two therapists, both therapists participated in the project.

Twenty-nine therapists were psychiatrists, five were psychologists, and two were social workers. Four psychiatrists and four psychologists were still in training during most or all of their patients’ treatment. Eighteen had practiced for more than 10 years, and 11 of these 18 had practiced for 15 or more years. All participating psychiatrists provided both psychotherapy and medication management. In the seven cases in which psychotherapy was provided by a psychologist or social worker, medications were managed by a psychiatrist. None of the 36 therapists followed a structured treatment protocol.

Patients

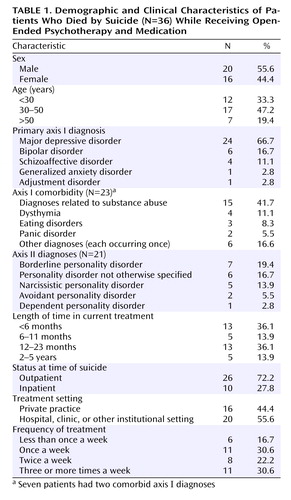

Table 1 summarizes the key demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Diagnoses were made by the therapists on the basis of clinical evidence rather than by use of a structured diagnostic schema. All diagnoses were confirmed in the workshops by using current DSM criteria; in a few cases, the original diagnosis was changed or expanded by group consensus.

Results

Six critical problems were identified in these cases.

Lack of Communication Between Therapists

Lack of communication between therapists created a serious problem in nine cases. Although 23 patients had been in treatment with another therapist during the 6 months before beginning the therapy during which they died, communications between the current and previous therapists were rare. In three cases, after the patient’s death, a former therapist shared information that might have helped resolve an impasse in the treatment. In two other cases, the patient was hospitalized just before the suicide. The lack of communication between the outpatient therapist and the hospital providers resulted in misjudgments about the patient’s suicide risk.

Lack of communication was most striking in four cases where a psychologist or social worker was providing psychotherapy and a psychiatrist was managing medication. The following case—one of two in which the two treatment providers were at the same institution—is illustrative. The patient, a man in his late 40s, had a several-year history of recurrent depression, suicidal ideation, and feelings of depersonalization. Unable to work, he had moved back into his parents’ home. He sought treatment at a medical center some distance away and was seen by an outpatient social worker for almost 3 years at intervals of 1–6 weeks. After the first year, he was assigned to a psychiatric resident for monthly medication management.

The social worker and the psychiatrist had electronic access to each other’s treatment notes, but they did not communicate directly. The social worker was aware that the patient was not taking medications as prescribed by the psychiatrist. Although she urged the patient to discuss this issue with the psychiatrist, she did not do so herself. Family problems were the predominant focus in the patient’s treatment. He had a strained relationship with his father but an intense, mutually dependent relationship with his mother, who had bipolar disorder and, like the patient, was largely housebound. The patient frequently discussed suicide with both the social worker and the psychiatrist. He admitted having a suicide plan, but he insisted he would not take action while his parents were alive because he “couldn’t do that to them.” Several months before the patient’s death, his father retired, radically altering the household routine. The mother became increasingly manic and dysfunctional but refused to get treatment.

In his last session with the psychiatrist, 9 days before his death, the patient tearfully described his mother’s deterioration. He then revealed that he had looked at a gun in a store and imagined putting it in his mouth. Both the psychiatrist and the patient were frightened by the fantasy. The psychiatrist considered hospitalizing the patient but accepted his promise that he would not kill himself.

The day before his suicide, the patient met with the social worker. He remained distressed about his mother. He admitted feeling suicidal but repeated that he could not kill himself while his parents were alive. The therapist was sufficiently alarmed to offer him more frequent visits or telephone support. The patient killed himself the next day.

Had the two treatment providers talked after the psychiatrist’s last session with the patient, they may have reassured each other that their concerns about potential suicide were exaggerated. However, it is also possible that their pooled information would have reinforced those concerns and led to a more proactive intervention.

Permitting Patients or Their Relatives to Control the Therapy

In 17 cases, therapists allowed the patient or the patient’s relative to control the course of the therapy. Suicidal patients frequently controlled their therapy, sometimes using the threat of suicide to do so. In three cases, the patient set certain conditions for living and insisted on the therapist’s support in meeting those conditions. In each instance the therapist complied, thinking that doing so was necessary to keep the patient in treatment and alive.

One such patient, a man in his 40s with bipolar disorder, told his therapist that he would kill himself unless he succeeded in opening a business within the next 6 months. He agreed to further treatment only on the condition that the therapist help convince his parents to give him the necessary financial backing. Several therapy sessions were spent strategizing about how this could be achieved. At a session that included the parents, they agreed to help, but substantial obstacles remained. When the business could not be opened on schedule, the patient became agitated and distressed, and the therapist suggested hospitalization. The patient declined but agreed to think about it. That night he hanged himself.

Two other patients more subtly exerted control by repeatedly bringing up or alluding to topics and then refusing to talk about them. The therapists accepted this behavior, largely out of fear of upsetting a potentially suicidal patient. In nine other cases, the patients’ need for control led them to determine whether and in what amounts they would take prescribed medications. In all such cases, the patients’ ability to work in therapy was seriously compromised, but the therapists felt that they had no choice but to go along, even in the few cases where patients stopped taking medication altogether.

In three inpatient cases, relatives were allowed to control critical treatment decisions. One therapist was reluctantly persuaded by a suicidal patient’s prominent uncle to give the patient a pass to attend a family birthday dinner. The patient absconded and killed himself. In the other two cases, the patients’ mothers pressured the therapists, against their better judgment, to begin planning the patients’ discharge prematurely; in both cases the patients killed themselves before the discharge.

Avoidance of Issues Related to Sexuality

In seven cases, the therapy was marked by an avoidance of sexual issues. Unaddressed conflicts related to sexuality were evident in two patients’ inability to engage in any type of sexual relationship. In three other cases, the therapists were aware of their patients’ conflicts related to homosexuality, but the patients’ sexuality was rarely, if ever, brought up. Patients gave ample evidence of sexual ambivalence in two additional cases, but this issue was left unexamined.

In one such case, a never-married man in his late 30s with major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, avoidant personality disorder, and substance abuse was receiving therapy from a social worker. He described long-standing sexual conflicts that he attributed to repressive parents and years of Catholic schooling. In his 20s he had several homosexual encounters that had left him feeling “deficient” as a man. Currently, he searched personal ads for a girlfriend and was increasingly angry and despondent at his lack of success. Sometimes he visited prostitutes, but he found these experiences unsatisfying. He was embarrassed about being single and avoided social occasions where most people would attend as couples.

He alluded in therapy to a co-worker who often teased him in a humiliating and enraging way. The therapist believed the co-worker was implying that the patient was homosexual, but the patient was not willing to discuss this subject, and the therapist chose not to pursue it. In his last session, the patient was angry and refused to sit down. Standing at the door, he announced that he was “fed up” and “finished” with work and with therapy and was “getting out now.” The therapist realized the danger and urged the patient to tell her what had happened. Instead of answering he left the session saying he would see her next week. He killed himself the next day. The therapist never learned what had so upset the patient.

Ineffective or Coercive Actions Resulting From the Therapist’s Anxiety

Therapists’ anxiety over the possibility of suicide interfered with their ability to treat their patients effectively in 11 cases. In three cases where the patients’ immediate suicidal intent was made clear in the final visit, the therapists felt unable to intervene or ask a colleague for help. In five cases, the therapist of an imminently suicidal patient suggested hospitalization but left the decision to the patient who, in each case, rejected it and took his life shortly thereafter.

In three additional cases, therapists’ anxiety and frustration led to actions that were harmful to treatment. One case involved a young man with major depressive disorder and avoidant personality disorder. After more than a year of inpatient treatment with virtually no improvement, he began to complain of feeling “brain dead.” He demanded electroconvulsive therapy and tried several times to electrocute himself. Aggravated by this behavior, the treatment team forced him to sign a contract to stop it. Under the threat of discharge, the patient appeared to comply. He was rewarded by being allowed to go on a staff-supervised outing during which he escaped and killed himself.

After the patient’s death, the treatment team noticed a note in the chart indicating that the patient had told a staff member that his compliant behavior had been an act. The treatment team’s attempt to force the patient to suppress his frustrations over his lack of progress resulted in a power struggle in which the patient seemed to perceive suicide as a victory.

Not Recognizing the Meanings of Patients’ Communications

In nine cases, the therapists failed to recognize the meaning of their patients’ communications.

In six cases, the therapists misunderstood or took too literally what their patients were saying, thus failing to recognize a mounting suicide crisis. In the case of the previously mentioned patient, whose mother became manic and unavailable after his father’s retirement, both the social worker and the psychiatrist sensed in their last sessions that the patient was in a suicide crisis. They were reassured, however, by the patient’s vow not to kill himself while his parents were alive. Rather than being concerned about hurting his parents, the patient seemed to be saying that he could not continue to live now that his mother had become emotionally unavailable. The loss of his mother, through the disruptions that followed the father’s retirement, appeared to propel him toward suicide.

In another case in which the therapist misunderstood the patient’s communication, a middle-aged man with a history of bipolar disorder and suicidal behavior became intensely anxious and unable to function socially and at work. He called his psychotherapist to report that he had accidentally taken a double dose of his medication and asked whether she thought he had made an inadvertent suicide attempt. She assured him he had not. Underlying the patient’s question appeared to be an increasing preoccupation with suicide that was left unaddressed. He killed himself that week.

In three other cases, the significance of a dream recounted by the patient was not fully perceived by the therapist. In one case, the overbearing mother of a patient with bipolar disorder convinced his therapist to foster the patient’s independence by discharging him from a halfway house where he was doing well. He confided to other patients a plan to drown himself using ropes and cinderblocks and showed them materials he had acquired. The therapist was informed and confiscated the materials but did not alter the discharge plan. In his last session, the patient discussed his anxiety about moving out on his own and then related a dream: “My father is sweeping me into the mouth of a big fish, and I get stuck in the fish’s throat…or maybe I get swallowed.” Shortly after this session, the patient drowned himself exactly as he had planned.

Until our workshop discussion many months later, the therapist had not recognized that the patient’s dream was likely communicating his awareness that the therapist was actively participating in his mother’s control of his treatment and his life. He may have felt that the therapist was as helpless to deal with her as were he and his invalid father. Perhaps he hoped that his death would at least stick in her throat.

Untreated or Undertreated Symptoms

In 17 cases, the patient exhibited major symptoms related to substance abuse, anxiety, and/or psychosis, but these problems were not adequately addressed. The most striking examples were 11 patients in whom obvious substance abuse was not treated. One patient, a middle-aged divorced businesswoman, entered therapy because of depression, loneliness, and low self-esteem. She was a heavy drinker and had a history of brief affairs with men she met in bars. Invariably she was hurt and depressed when these affairs ended. After her most recent rejection, her alcohol abuse increased. Although the therapist suspected the patient was drinking even more than she admitted, the therapist did not confront the patient with this suspicion, believing that the patient needed her support and approval. A few weeks later, the patient killed herself.

In 15 cases, the patient’s intense anxiety in the period preceding the suicide was not adequately treated. The danger of untreated anxiety in a suicidal patient is illustrated by the case of a middle-aged man who had been briefly hospitalized several times in the last year for severe depression, polysubstance abuse, and suicide attempts. In his last hospital stay, the patient became increasingly anxious when his request for long-term treatment was denied. Focused on his history of substance abuse and manipulative behavior, his treatment team did not prescribe anxiolytic medication. Increasingly desperate, the patient smuggled a gun into the hospital and shot himself.

In three other cases, the patient’s clearly psychotic symptoms were either undiagnosed or untreated. One such patient, the wife of a successful professional, became severely depressed after her grown children moved away from home. Despite treatment with antidepressants and psychotherapy, her condition worsened. Triggered in part by unrealistic financial concerns, she developed delusional fears of impoverishment and abandonment. These fears appeared to have roots in her childhood experience of being temporarily placed in an orphanage when her parents became impoverished. A few weeks before her death, the patient scratched her neck with her husband’s pocketknife. Realizing her condition was worsening, her therapist recommended increasing her antidepressant medication but did not consider adding a neuroleptic. The patient killed herself shortly thereafter.

Discussion

It is important not to be judgmental in reviewing this case material, as the problems that we, and the therapists themselves, identified became evident largely through retrospective review. Although inadequate interventions could be identified in virtually all cases we have studied of patients who died by suicide while in treatment, these retrospective findings do not mean that these suicides could have been predicted or prevented. Even if the problems we noted had been avoided or successfully resolved, there is no certainty that the outcome for these patients would have been different.

It should also be emphasized that many of these problems can and do occur in the treatment of difficult-to-treat patients who are not suicidal. The added gravity common problems assume when suicide is a risk, however, invariably involves unique anxieties related to the possibility that despite the therapist’s best efforts, the patient may kill himself and the therapist may be blamed. Therapists’ fear that a patient may commit suicide frequently impedes their ability to deal effectively with the danger (14). Paradoxically, we have found that therapists who recognized that a patient was in a suicide crisis are often shocked when the patient actually kills himself or herself (15), suggesting that some therapists deal with that anxiety by denying that what seems possible, or even likely, could actually happen. Regardless of how it is managed, it is clear that such anxiety, and the anger it frequently triggers in those who treat suicidal patients, may understandably threaten clinical judgment and contribute to problems in therapy.

Recommendations for Treatment

We offer the following recommendations, which we hope will help address a clearly apparent gap in therapists’ clinical training in psychotherapy with suicidal patients.

| 1. | Active communication among all treatment providers involved in the care of a suicidal patient fosters the sharing of critical information and provides the benefits of support and additional perspectives. Improved communications should be encouraged through better clinical training and institutional policies that require patient information to be shared between providers within the same service system (16). | ||||

| 2. | Problems related to patients’ control of the therapy are of particular concern with suicidal patients because suicide is frequently an aspect of their need for control. Like the patient who made his desire to open his own business the focal point of the therapy, some suicidal patients seek control by making their continuing to live contingent on a future outcome, frequently setting conditions that are impossible to fulfill (17). Although therapists’ anxiety over a possible suicide can lead them to support the patients’ goals, exploring what patients are trying to communicate by setting conditions for living is more likely to be effective than intervening to help patients meet the unrealistic conditions they have defined. | ||||

| 3. | Therapists’ anxiety may make them reluctant to press suicidal patients who hint at critical subjects and then refuse to discuss them. The therapist’s ability to help the patient explore such topics may be crucial in obtaining insight into the basis for the patient’s suicidal feelings. | ||||

| 4. | Patients’ control over medication presents a particularly difficult dilemma in treating suicidal patients. Although confronting patients about control over or discontinuation of medication carries the risk that they will terminate treatment, therapists’ passive permissiveness in regard to patients’ (or their relatives’) attempts to control the treatment commonly engenders anxiety, anger, and disconnection in suicidal patients (18). Explicitly exploring the patient’s feelings about medication noncompliance is essential. | ||||

| 5. | Although sexual feelings, fantasies, and behavior may not appear to be centrally important to a patient considering suicide, such a view overlooks much of what we have learned about the psychodynamics of suicide and patients’ tendency to conflate sexual intimacy, destructiveness, and self-destructiveness (19). Further, discussion of sexuality can strengthen the connectedness between therapist and patient, improving the likelihood of the therapist’s recognizing an unfolding suicide crisis and increasing the potential strength of the therapeutic alliance as a deterrent to suicide. | ||||

| 6. | Although decisions regarding hospitalization are among the most difficult aspects of treating suicidal patients, it is essential for the therapist to be clear and decisive in dealing with this issue. Presenting hospitalization as necessary to prevent the patient’s suicide may make hospitalization acceptable to patients who want relief from suicidal feelings, but suicide prevention as a goal is often not shared by patients bent on suicide. By exploring the desperation and other intense feelings that underlie the desire for suicide, therapists may be able to help patients accept hospitalization as a means of obtaining short-term relief without the sense that they are surrendering control over the choice of whether to live. When a therapist is faced with a patient who appears to be imminently suicidal but is unwilling to be hospitalized, forced hospitalization is preferable to allowing the patient to go home and think about it. For patients in a suicide crisis, the prospect of losing control over the choice to live may push them to act while they are still able to do so. | ||||

| 7. | Dreams reported by a patient in a suicide crisis, like those of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (20), often express feelings with minimal disguise and can provide both the therapist and the patient with critically important information. Inquiring about the dreams of patients who are believed to be suicidal can help therapists ascertain suicidal preoccupations or intentions that are not being directly communicated. | ||||

| 8. | The omission of appropriate medication in some of the cases we studied confirmed findings reported by others of inadequate medication treatment in patients who died by suicide (21) or who attempted suicide (22). Particular care needs to be taken to recognize and to effectively treat anxiety (23) and psychotic symptoms (24) in suicidal depressed patients. Diagnosing psychotic symptoms may be especially difficult when delusions are nonbizarre and seem to have an understandable source in the patient’s history. | ||||

| 9. | Addressing and treating suicidal patients’ substance abuse, particularly alcohol abuse (25), is critical in effective treatment of other problems, including lack of response to antidepressant medication. | ||||

Limitations

Because the therapists who participated in this project were of necessity volunteers, we cannot estimate how typical they are of the population of therapists who have experienced a patient’s suicide. It is possible they may have been more than ordinarily disturbed about the suicide of their patients, perhaps because of unusually difficult problems encountered in treatment. It is also possible that the therapists who volunteered to have their cases scrutinized were less troubled about the treatment they provided than were those who did not come forward. The reactions of participating therapists suggested that both possibilities were represented (15). At the same time, the consistency of so much of what they revealed about problems in treating suicidal patients—despite their differences in training, experience, therapeutic orientation, and personal style—suggests that the findings reported here have widespread applicability.

Persons who kill themselves while in psychotherapy are not representative of all who die by suicide (26). In the most obvious respect, occurrences within the treatment process itself frequently become factors in driving patients’ suicides. Yet the suicidal patients who enter therapy are the ones clinicians have the greatest opportunity to help. Examining problems encountered in psychotherapy with suicidal patients should help to improve the effectiveness of their treatment.

|

Received Oct. 12, 2004; revisions received Dec. 15, 2004, and Jan. 25, 2005; accepted March 7, 2005. From the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; the Department of Psychiatry, New York Medical College, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Hendin, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 120 Wall St., 22nd Floor, New York, NY 10005; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Mental Illness Foundation and Janssen Pharmaceutica.

1. Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

2. Rudd MD, Dahm PF, Rajab MH: Diagnostic comorbidity in persons with suicidal ideation and behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:928–934Link, Google Scholar

3. Rudd MD: An integrative conceptual and organizational framework for treating suicidal behavior. Psychotherapy 1998; 35:346–360Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Rudd MD, Joiner TE, Jobes DA, King CA: The outpatient treatment of suicidality: an integration of science and recognition of its limitations. Prof Psychol Res Pr 1999; 30:437–446Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery FG: Cognitive Theory of Depression. New York, Guilford, 1979Google Scholar

6. Lerner M, Clum G: Treatment of suicide ideators: a problem-solving approach. Behav Ther 1990; 21:403–411Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Salkovskis PM, Atha C, Storer D: Cognitive-behavioral problem solving in the treatment of patients who repeatedly attempt suicide: a controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:871–876Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Freeman A, Reinecke MA: Cognitive Therapy of Suicidal Behavior. New York, Springer, 1993Google Scholar

9. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Linehan MM: Behavioral treatments of suicidal behaviors: definitional obfuscation and treatment outcomes. Ann NY Acad Sci 1997; 836:302–328Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rudd MD, Joiner TE, Rajab MH: Treating Suicidal Behavior: An Effective, Time-Limited Approach. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

12. Guthrie E, Kapur N, Mackway-Jones K, Chew-Graham C, Moorey J, Mendel E, Francis FM, Sanderson S, Turpin C, Boddy G: Predictors of outcome following brief psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy for deliberate self-poisoning. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003; 37:532–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C: Combined pharmacology and psychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:714–719Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Birtchnell J: Psychotherapeutic considerations in the management of the suicidal patient. Am J Psychother 1983; 37:24–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, Haas AP, Wynecoop S: Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:2022–2027Link, Google Scholar

16. Meyer D: Split treatment and coordinated care with multiple mental health clinicians: clinical and risk management issues. Primary Psychiatry 2002; 9:59–60Google Scholar

17. Gutheil TG, Schetky D: A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1502–1507Link, Google Scholar

18. Plakun EM: Making the alliance and taking the transference in work with suicidal patients. J Psychother Pract Res 2001; 10:269–276Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kernberg OF: Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. New York, Jason Aronson, 1976Google Scholar

20. Hendin H: The psychodynamics of suicide. Int Rev Psychiatry 1992; 4:157–167Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Isacsson G, Boethius G, Bergman U: Low level of antidepressant prescription for people who later commit suicide: 15 years of experience from a population-based drug database in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:444–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Oquendo MA, Kamali M, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Malone KM, Brodsky BS, Sackeim HA, Mann JJ: Adequacy of antidepressant treatment after discharge and the occurrence of suicidal acts in major depression: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1746–1751Link, Google Scholar

23. Fawcett J: Treating impulsivity and anxiety in the suicidal patient. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 932:94–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Warman DM, Forman EM, Henriques GR, Brown GK, Beck AT: Suicidality and psychosis: beyond depression and hopelessness. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2004; 34:77–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Connor KT, Chiapella P: Alcohol and suicidal behavior: overview of a research workshop. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004; 28 (5 suppl):2S-5SGoogle Scholar

26. Harris CE, Barraclough B: Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:205–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar