Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Utilization of Mental Health Services in Two American Indian Reservation Populations: Mental Health Disparities in a National Context

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) provided estimates of the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders and utilization of services for help with those disorders in American Indian populations. Completed between 1997 and 1999, the AI-SUPERPFP was designed to allow comparison of findings with the results of the baseline National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), conducted in 1990–1992, which reflected the general United States population. METHOD: A total of 3,084 tribal members (1,446 in a Southwest tribe and 1,638 in a Northern Plains tribe) age 15–54 years living on or near their home reservations were interviewed with an adaptation of the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The lifetime and 12-month prevalences of nine DSM-III-R disorders were estimated, and patterns of help-seeking for symptoms of mental disorders were examined. RESULTS: The most common lifetime diagnoses in the American Indian populations were alcohol dependence, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and major depressive episode. Compared with NCS results, lifetime PTSD rates were higher in all American Indian samples, lifetime alcohol dependence rates were higher for all but Southwest women, and lifetime major depressive episode rates were lower for Northern Plains men and women. Fewer disparities for 12-month rates emerged. After differences in demographic variables were accounted for, both American Indian samples were at heightened risk for PTSD and alcohol dependence but at lower risk for major depressive episode, compared with the NCS sample. American Indian men were more likely than those in NCS to seek help for substance use problems from specialty providers; American Indian women were less likely to talk to nonspecialty providers about emotional problems. Help-seeking from traditional healers was common in both American Indian populations and was especially common in the Southwest. CONCLUSIONS: The results suggest that these American Indian populations had comparable, and in some cases greater, mental health service needs, compared with the general population of the United States.

Past research among American Indians has revealed high rates of mental disorders, especially alcohol abuse/dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1–6). Substantial tribal differences in the prevalence of certain problems—notably alcohol and drug use (7, 8)—underscore the importance of anticipating and accounting for social and cultural diversity in relation to such problems. Previous studies among American Indians, however, have used diagnostic measures and sampling methods that preclude comparison across tribes and comparison with national estimates. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Surgeon General’s report, Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity(9), concluded that we lack even the most basic information about the relative mental health burdens borne by American Indians.

The American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) was designed to allow direct comparisons between the baseline National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) sample and two American Indian tribes. The NCS, which assessed DSM-III-R diagnoses, has guided the national agenda regarding mental health planning over the last decade and thus provides an important point of reference for epidemiological studies of this nature. Here, we report the lifetime and 12-month prevalences of selected DSM-III-R disorders for two well-defined American Indian populations within the context of the NCS and examine differential risk for disorder by tribe, with adjustment for demographic correlates. We also examine patterns of help-seeking for symptoms of mental disorders.

Previous findings (1, 2, 4–6) led us to hypothesize that rates of alcohol use disorder would be higher in these tribes, compared to the U.S. population as reflected in NCS. Our own studies among American Indian adolescents (8) suggested that we also would observe significant tribal differences, namely a higher prevalence of alcohol use disorder in the Northern Plains than in the Southwest. There was good reason as well to suspect that the prevalences of major depression and PTSD in both tribes would exceed those found by the NCS for the general U.S. population (3, 5). The paucity of relevant literature, however, rendered help-seeking among American Indians much more enigmatic, although we were confident that traditional healing resources would assume a prominent role in this process (10, 11). The results of this inquiry represent an important step toward addressing the Surgeon General’s mandate to better describe the mental health disparities that plague American Indian communities.

Method

Sample

The AI-SUPERPFP populations of inference were 15–54-year-old enrolled members of two closely related Northern Plains tribes and a Southwest tribe living on or within 20 miles of their respective reservations at the time of sampling (1997). To protect the confidentiality of the participating communities (12), we refer to them by these general descriptors rather than specific tribal names.

Tribal rolls formed the sampling universe; these records list all individuals meeting the legal requirements for recognition as tribal members. Stratified random sampling procedures were used with strata defined by cultural group, gender, and age (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 years). Records were selected randomly for inclusion into replicates, which were then released as needed to reach our goal of approximately 1,500 interviews per tribe.

As described in greater detail elsewhere (13), an elaborate location procedure was developed that involved searches of public records and queries of family members and knowledgeable community “key informants”; supervisors rather than interviewers made the final location determination. In the Southwest and Northern Plains, respectively, 46.6% and 39.2% of those listed in the tribal rolls were found to be living on or near the reservations. Of those located and found eligible, 73.7% in the Southwest (N=1,446) and 76.8% in the Northern Plains (N=1,638) agreed to participate, with lower response rates for male tribal members and younger tribal members. In all analyses presented here, sample weights were used to account for differential selection probabilities across all strata and for patterns of nonresponse.

Data Collection

Tribal approvals were obtained before project initiation. Informed consent was obtained from all adult respondents; for minors, parental/guardian consent was obtained before requesting the adolescent’s assent. Ci3 Version 2 (14) was used to develop a computer-assisted personal interview that greatly facilitated administration of the complex diagnostic protocol. Tribal members who had received intensive training in research and interviewing methods read questions to the participants from a laptop computer screen and entered interviewees’ responses. For two sections of the interview—assessment of past criminal behaviors and HIV knowledge and behaviors (in the Northern Plains group only)—participants entered their responses directly into the computer.

Measures

The AI-SUPERPFP interview not only assessed mental disorder and help-seeking but also included measures of physical health, health-related quality of life, stress, and important psychosocial constructs (such as social support and coping). Both the protocol and the training manual are available on our web site (http://www.uchsc.edu/ai/ncaianmhr/research/superpfp.htm).

Diagnoses

Lifetime and 12-month mental health disorders were assessed, in English, by using the NCS’s University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) adapted for use in American Indian communities in the context of a previous study (3). That adaptation included several modifications that were based on the results of focus group reviews by community members and service providers. For example, psychoses and mania were excluded because of concerns regarding the cultural validity of the measures. (For example, inquiries about hallucinations in cultures where the seeking of visions is nurtured must be more nuanced than would be possible in an interview conducted by lay interviewers.) Simple and social phobias and agoraphobia were deleted from consideration because of concerns about respondent burden. As a result, nine disorders were assessed in AI-SUPERPFP: major depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, PTSD, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence. Aggregations included any depressive disorder (major depressive episode or dysthymic disorder), any anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or PTSD), any depressive/anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence), and any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

Help-Seeking

Questions about help-seeking were included in each diagnostic module and asked of all individuals who endorsed at least some symptoms of the disorder. These questions were patterned after the NCS questions but were adapted to reflect the service ecologies of American Indian reservation communities. Questions about traditional healers (including medicine men and spiritual and religious leaders) were included, in addition to questions about a wide range of specialty care providers (both mental health and substance abuse treatment providers) and other medical professionals. The present analyses focused on lifetime help-seeking for any depressive/anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder, and any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

NCS Sample

Our comparison to the general U.S. population used the baseline NCS, described in detail elsewhere (15). The NCS was conducted in a stratified, multistage area probability sample of 8,098 U.S. residents age 15–54 years in 1990–1992. As noted earlier, the help-seeking measures were located within the diagnostic modules. The NCS diagnoses reported here are restricted to those assessed in AI-SUPERPFP.

Analyses

Variable construction was completed with SPSS (16) and SAS (17); all inferential analyses were conducted with Stata’s “svy” procedures (18) with sample and nonresponse weights (19). Generally, the NCS diagnostic algorithms were used for the AI-SUPERPFP data. An exception was made for the diagnosis of major depressive episode. As reported in the companion article in this issue (20), our initial analyses of data for depressive disorders demonstrated that the requirement for major depressive episode symptoms to co-occur within an episode and not to be due to a physical illness, medications, or substance use decreased the validity of the AI-SUPERPFP CIDI major depressive episode diagnosis, while dramatically decreasing prevalence. Thus, the major depressive episode diagnoses reported here did not include the co-occurrence or physiological/medical rule-out stipulations for the AI-SUPERPFP samples but did for the NCS sample; as such, the AI-SUPERPFP rates are higher than might otherwise be the case. NCS did not include help-seeking questions in its PTSD module; thus, for purposes of these comparisons, our results for help-seeking do not include data on help-seeking for PTSD for either the AI-SUPERPFP samples or the NCS sample.

Prevalence estimates and 99% confidence intervals are reported for six groups: male and female members of the Southwest, Northern Plains, and NCS samples. Differences between specific groups were identified by means of nonoverlapping confidence intervals. A combined AI-SUPERPFP/NCS data set was analyzed with logistic regression methods to determine whether the tribal samples were at differential risk for disorder, after a common set of demographic variables was taken into consideration. Separate logistic regression analyses were calculated for each lifetime and 12-month diagnosis. To assess whether the tribes were at differential risk for each diagnosis, logistic regression analyses were conducted with dummy variables denoting tribal membership entered along with those denoting demographic factors (gender, age, formal educational attainment, poverty, and marital status). The primary hypothesis addressed was that tribal disparities would remain despite adjustment for possible demographic confounding factors. Only the odds ratios for each tribe are reported. (The results for the demographic correlates are available on request.) Because of the large size of these samples and the number of analyses, we adopted a conservative stance in interpreting regression coefficients, focusing only on those with p values less than 0.01.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

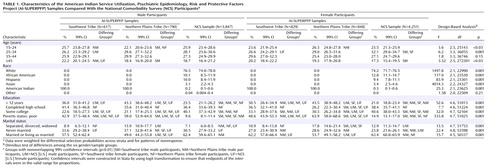

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the male and female participants in the AI-SUPERPFP and NCS samples. The NCS sample was weighted back to the U.S. population and thus comprised primarily white participants with substantial numbers of African American and Hispanic participants; American Indian/Alaska Natives made up about 1% of the NCS sample. The comparison population of inference was the U.S. general population; thus, the full NCS sample was retained for these analyses. Because of differential migration to urban areas for employment, fewer Southwest male participants were living on or near the reservations than might be expected; thus, 57% of the participants in this sample were women. The modal categories for educational attainment varied by sample, as follows: less than high school for the Northern Plains sample, high school for the Southwest sample, and at least some college for the NCS sample. The most dramatic difference between the American Indian and NCS samples was in poverty status.

Disparities in Prevalence of DSM-III-R Disorders

Lifetime rates

Lifetime prevalence estimates of DSM-III-R disorders, by gender within each sample, are shown in Table 2. Sample differences within gender are highlighted here. Women in the NCS sample were more likely than all others to qualify for lifetime major depressive episode, and NCS men were more likely to report major depressive episode than were Northern Plains men. NCS women were more likely to report dysthymic disorder, compared to Northern Plains women. Largely because of their high prevalence of major depressive episode, NCS women were more likely than all other samples to qualify for the aggregate category of any depressive disorder. Within each sample, men had lower overall rates of any depressive disorder, compared with women, but this gender difference was significant only in the NCS sample.

Lifetime rates of two of the three anxiety disorders assessed in AI-SUPERPFP—panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder—showed little variability across samples. Culture and gender differences were evident for PTSD, however. Both American Indian samples were more likely to meet the criteria for PTSD than their NCS counterparts, and men were less likely to qualify for a PTSD diagnosis than were their female counterparts in all samples. Overall, NCS men were the least likely group to qualify for this diagnosis. The patterns for the aggregate category of any anxiety disorder mirrored those of the most common AI-SUPERPFP anxiety disorder, PTSD. When depressive and anxiety disorders were combined, women in all samples were more likely to meet the criteria for a diagnosis than were men, but no differences were found between samples.

Substantial variability was evident in the lifetime rates of only one of the four substance use disorders—alcohol dependence. The highest rates of alcohol dependence were among American Indian men, who were significantly more likely to qualify for this disorder than were all other groups. NCS men and Northern Plains women had the next highest rates; these rates were significantly lower than those for American Indian men but were still higher than those for Southwest women and NCS women. A gender disparity was clear within each sample and was greatest in the Southwest tribe, where the rate for women was 28% of the rate for men; the gender disparity was moderate in the NCS sample, where the rate for women was 41% of that for men; and least in the Northern Plains tribe, where the women’s rate was 67% of that for men.

Lifetime rates of any AI-SUPERPFP disorder revealed disparities across gender and culture groups. Southwest men were more likely to qualify for a DSM-III-R disorder than were NCS men, but the rate for Northern Plains men did not differ significantly from that for either the Southwest men or the NCS men. Among women, those from the Northern Plains tribe were at higher risk than were NCS women. These overall rates reflected those for the most common individual disorders, with alcohol dependence most common for all three male samples, alcohol dependence and PTSD about equally common for the Northern Plains women, PTSD most common for the Southwest women, and major depressive episode most common for the NCS women. Furthermore, whereas major depressive episode was the most common non-substance-use disorder for the NCS samples, PTSD ranked first for the American Indian samples, although the difference was significant only for women.

12-month rates

Estimates of the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders within the past year are shown in Table 3. Generally, although the pattern for 12-month rates was similar to that for the lifetime rates, many fewer statistical differences were found in the 12-month rates. Once again, major depressive episode and any depressive disorder were more common among NCS women than in the other samples, except Southwest women. A striking difference between lifetime and 12-month rates appeared in the prevalence of PTSD. Whereas lifetime rates showed dramatic tribal and gender effects, 12-month rates showed relatively little variability. Although a clear gender difference remained for alcohol dependence and, more generally, for any substance use disorder, the only sample differences were between Northern Plains women and both Southwest and NCS women. No sample or gender differences were evident for the aggregate category of any AI-SUPERPFP disorder in the past year.

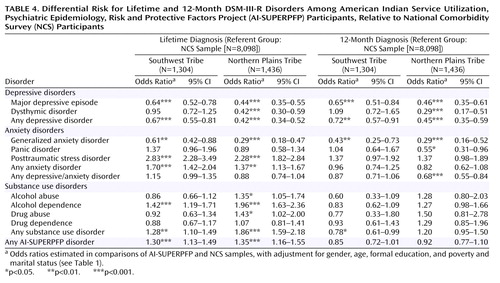

Multivariate Assessment of Differential Risk for Disorder

Table 4 presents findings for the differential risk for the Southwest and Northern Plains samples, compared to the NCS sample, for specific and aggregated disorders, with adjustment for gender, age, formal educational attainment, poverty, and marital status. Both tribal samples were at lower risk for lifetime and 12-month major depressive episode and generalized anxiety disorder, compared with the NCS sample, but only the Northern Plains sample was at lower risk for lifetime and 12-month dysthymic disorders. Both tribes were at greater risk for lifetime but not 12-month PTSD and alcohol dependence. Largely because of their greater risk for lifetime PTSD and alcohol dependence, the tribal samples were at greater risk for the aggregate category of any lifetime (but not 12-month) AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

Relative Rates of Help-Seeking

Table 5 shows that the rates of lifetime help-seeking by participants who met the criteria for a diagnosis were generally low. Typically, fewer than 30% talked to or received services from specialty providers, broadly defined, and fewer sought help for their symptoms from other medical providers. Focusing on disparities, among those with substance use disorders, NCS men were less likely to talk to specialty providers for substance use problems than were both Southwest and Northern Plains men. On the other hand, for both the depressive/anxiety and any AI-SUPERPFP disorder categories, both American Indian samples of women were less likely to seek care in other medical settings than were NCS women; a similar pattern was found for Northern Plains men with any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

Although comparable assessments of traditional healing services were not included in NCS, the description of such services is essential to understanding help-seeking in American Indian communities. Table 5 shows that such help-seeking for any disorder was more common in the Southwest tribe than in the Northern Plains tribe. Perhaps most striking, however, is that seeking help from traditional sources was more common than seeking help from other providers for Southwest men and women with any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

Discussion

Limitations in the AI-SUPERPFP sample, study design, and instrumentation have been discussed at length elsewhere (13). Briefly, the AI-SUPERPFP samples, while well defined and justified, were limited in cultural representation, age range, and residence. As with other studies of this type, AI-SUPERPFP relied on retrospective self-reports of psychiatric symptoms as reported to lay interviewers using highly structured protocols. Furthermore, joint analyses of data sets such as AI-SUPERPFP and NCS have methodological limitations. The data collection periods necessarily varied as did the methods—at least to a certain extent. The NCS data were collected in 1990–1992; the AI-SUPERPFP data, between 1997 and 1999. Further, by focusing on the disorders assessed in AI-SUPERPFP, this report differs from others that have used the NCS data, for example, by excluding phobic disorders, bipolar disorder, and nonaffective psychoses. The AI-SUPERPFP CIDI was carefully adapted to enhance cultural validity. In most cases, these adaptations consisted of adding questions while retaining the NCS wording wherever possible (13). The rates reported here did not include most of these enhancements, and, with the exception of major depressive episode, all AI-SUPERPFP diagnoses were determined with the same algorithm that was used in NCS. Further analyses are needed to examine the cultural validity of the AI-SUPERPFP CIDI and, more generally, of DSM-defined disorders.

These limitations notwithstanding, this report describes (for the first time, to our knowledge) the prevalence of common psychiatric disorders and associated help-seeking in a comparative context. Comprehensive assessments of adults within American Indian communities have been rare, but existing research has shown high rates of disorder, especially disorder related to alcohol use and trauma (1, 2, 4–6). As with AI-SUPERPFP, these studies found alcohol use disorders to be most common; however, the alcohol use disorder rates reported here are substantially lower than those reported in previous efforts that used different assessment methods and in which participants were not selected with stratified random sampling procedures. Tribal representation also varied. Thus, methodological differences likely account for these discrepancies.

This work adds to the growing literature on mental health disparities among ethnic and racial populations in the United States. The distribution of DSM-defined disorders in these reservation-based tribal populations differed by both tribe and gender from that in the U.S. general population (as depicted by the NCS sample). Lifetime rates of any disorder were higher in Southwest men (but not Northern Plains men), compared to men in the NCS sample. Women in the Northern Plains tribe (but not in the Southwest tribe) were at higher risk than were the women in the NCS sample. Examination of data for individual disorders indicated that, among men, both the American Indian samples had higher rates of alcohol dependence and PTSD, compared to others in the United States, rendering these samples at higher risk for substance use disorders and anxiety disorders overall. Even with the more liberal operationalization of major depressive episode for AI-SUPERPFP (specifically, the exclusion of the requirement of at least three symptoms co-occurring during an episode and the stipulation that symptoms not be due to physiological effects or medical conditions), three of the four American Indian samples—Northern Plains men, Northern Plains women, and Southwest women—reported lower rates of major depressive episode, compared to the NCS sample. Although Northern Plains men were at higher risk for alcohol use disorders, their lower rate of major depressive episode rendered their overall prevalence rate for all disorders considered in AI-SUPERPFP comparable to that for U.S. men. Among women, both American Indian samples were at higher risk for PTSD, compared to women in the NCS sample. Northern Plains women were at lower risk for dysthymic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder but had a rate of alcohol dependence more than twice that of either U.S. or Southwest women and were, thus, at greater risk for any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

These patterns emerge even more clearly once the demographic differences between samples were included in the models of estimation. In these multivariate analyses, both American Indian tribes were at higher risk for a lifetime DSM-III-R disorder but not for a 12-month disorder, compared to the NCS sample. Focusing on individual disorders, the tribes were at lower risk for both lifetime and 12-month major depressive episode and generalized anxiety disorder and at higher risk for lifetime, but not 12-month, PTSD and alcohol dependence.

Such findings are both similar to and different from reports regarding other ethnic and racial minorities in the United States. Rates of depressive disorders are often reported to be lower among African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans, compared to whites (9, 21). Similarly, PTSD is often associated with the struggles of living in impoverished communities, although, to our knowledge, most of this research has been limited to urban contexts (22). American Indians in poor rural communities are also at heightened risk of trauma and resultant PTSD (3, 23). Compared to whites, African Americans and Asian Americans tend to have lower rates of substance use disorders, and Hispanics often have generally comparable rates (21). A study of Mexican Americans found that those born in the United States were at higher risk for alcohol dependence, compared to those born in Mexico (24). Similarly, Southwest women, as the carriers of tradition in this matrilineal culture, may have greater ties than others in AI-SUPERPFP to their Native ways and thus be at less risk for the development of alcohol use disorders. Although such findings argue against stereotyped conclusions about the extent of alcohol problems in American Indian communities, clear disparities in risk for alcohol dependence existed for three of the four American Indian samples defined by tribe and gender.

The prevalence rates of the less common AI-SUPERPFP disorders—dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder—provide additional information about mental health disparities. The pattern for dysthymic disorder generally reflected that for major depressive episode: Where differences occurred, the Northern Plains participants were less likely to meet the criteria for dysthymic disorder, compared with the other samples. Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was less common among the Northern Plains women than among U.S. women. The rates of lifetime and 12-month panic disorder and 12-month generalized anxiety disorder were generally comparable in the AI-SUPERPFP and NCS samples.

Mental health services for American Indians are acknowledged to be scarce (9, 25, 26). Our findings suggest that the rate of help-seeking for substance use disorders was relatively high in the American Indian samples. The exclusion of PTSD from the help-seeking analyses and the low prevalence of major depressive episode precluded a powerful test of relative help-seeking for depressive/anxiety disorders. Even so, American Indian women were less likely to seek help for depressive/anxiety disorders from nonspecialty providers. Not considered here is whether the help sought was considered efficacious and/or was of sufficient duration to be helpful (9). The reliance on traditional resources—especially in the Southwest—is a consistent finding (10) and underscores the need to better understand the importance of such healing in the service ecology of American Indians.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 3, 2003; revisions received June 3 and July 29, 2004; accepted Oct. 1, 2004. From the American Indian and Alaska Native Programs, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, Aurora. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Beals, American Indian and Alaska Native Programs, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, MS F800, PO Box 6508, Aurora, CO 80045-0508; [email protected] (e-mail). The study was supported by NIH grants R01 MH-48174 (Dr. Manson and Dr. Beals, principal investigators), P01 MH-42473 (Dr. Manson, principal investigators), R01 DA-14817 (Dr. Beals, principal investigator), and R01 AA-13420 (Dr. Beals, principal investigator). National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) data were made available by the International Consortium of Political and Social Research; NCS was supported by the following grants with R. Kessler as principal investigator: NIH grants R01 MH/DA-46376 and R01 MH-49098 and grant 90135190 from the William T. Grant Foundation. In addition to the authors named at the beginning of the article, the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) team includes Cecelia K. Big Crow, Dedra Buchwald, Buck Chambers, Michelle L. Christensen, Denise A. Dillard, Karen DuBray, Paula A. Espinoza, Candace M. Fleming, Ann Wilson Frederick, Diana Gurley, Lori L. Jervis, Shirlene M. Jim, Carol E. Kaufman, Ellen M. Keane, Suzell A. Klein, Denise Lee, Monica C. McNulty, Denise L. Middlebrook, Laurie A. Moore, Tilda D. Nez, Ilena M. Norton, Heather D. Orton, Carlette J. Randall, Angela Sam, James H. Shore, Sylvia G. Simpson, Paul Spicer, and Lorette L. Yazzie. The authors thank interviewers and computer/data management and administrative staff members Anna E. Barón, Amelia T. Begay, Cathy A.E. Bell, Mary Cook, Helen J. Curley, Mary C. Davenport, Rhonda Wiegman Dick, Marvine D. Douville, Geneva Emhoolah, Fay Flame, Roslyn Green, Billie K. Greene, Jack Herman, Tamara Holmes, Shelly Hubing, Cameron R. Joe, Louise F. Joe, Cheryl L. Martin, Jeff Miller, Robert H. Moran Jr., Natalie K. Murphy, Ralph L. Roanhorse, Margo Schwab, Jennifer Settlemire, Donna M. Shangreaux, Matilda J. Shorty, Selena S. S. Simmons, Jennifer Truel, Lori Trullinger, Jennifer M. Warren, Theresa (Dawn) Wright, Jenny J. Yazzie, and Sheila A. Young; Methods Advisory Group members Margarita Alegria, Evelyn J. Bromet, Dedra Buchwald, Peter Guarnaccia, Steven G. Heeringa,Ronald Kessler, R. Jay Turner, and William A. Vega; and the tribal members who so generously answered all the questions asked of them.

1. Kunitz SJ, Gabriel KR, Levy JE, Henderson E, Lampert K, McCloskey J, Quintero G, Russell S, Vince A: Risk factors for conduct disorder among Navajo Indian men and women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:180–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kunitz SJ, Gabriel KR, Levy JE, Henderson E, Lampert K, McCloskey J, Quintero G, Russell S, Vince A: Alcohol dependence and conduct disorder among Navajo Indians. J Stud Alcohol 1999; 60:159–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Beals J, Manson SM, Shore JH, Friedman M, Ashcraft M, Fairbank JA, Schlenger WE: The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among American Indian Vietnam veterans: disparities and context. J Trauma Stress 2002; 15:89–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Shore JH, Kinzie JD, Hampson JL, Pattison EM: Psychiatric epidemiology of an Indian village. Psychiatry 1973; 36:70–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kinzie JD, Leung PK, Boehnlein J, Matsunaga D, Johnston R, Manson SM, Shore JH, Heinz J, Williams M: Psychiatric epidemiology of an Indian village: a 19-year replication study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:33–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Robin RW, Chester B, Rasmussen JK, Jaranson JM, Goldman D: Prevalence, characteristics, and impact of childhood sexual abuse in a Southwestern American Indian tribe. Child Abuse Negl 1997; 21:769–787Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. May PA: Overview of alcohol abuse epidemiology for American Indian populations, in Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Edited by Sandefur GD, Rindfuss RR, Cohen B. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996, pp 235–261Google Scholar

8. Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Holmes T: Marijuana use among American Indian adolescents: a growth curve analysis from ages 14 through 20. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:72–78Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. US Department of Health and Human Services: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity, Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

10. Gurley D, Novins DK, Jones MC, Beals J, Shore JH, Manson SM: Comparative use of biomedical services and traditional healing options by American Indian veterans. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:68–74Link, Google Scholar

11. Buchwald DS, Beals J, Manson SM: Use of traditional health practices among Native Americans in a primary care setting. Med Care 2000; 38:1191–1199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Norton IM, Manson SM: Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: navigating the cultural universe of values and process. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:856–860Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P, the AI-SUPERPFP Team: Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Cult Med Psychiatry 2003; 27:259–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ci3 Version 2. Evanston, Ill, Sawtooth Technologies, 1995Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. SPSS 11.0 for Windows. Chicago, SPSS, 2002Google Scholar

17. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 8.2. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2001Google Scholar

18. Stata Reference Manual: Release 8.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

19. Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1977Google Scholar

20. Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Simpson S, Spicer P, AI-SUPERPFP Team: Prevalence of major depressive episode in two American Indian reservation populations: unexpected findings with a structured interview. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1713–1722Link, Google Scholar

21. Zhang AY, Snowden LR: Ethnic characteristics of mental disorders in five US communities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 1999; 5:134–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Manson S, Beals J, O’Nell T, Piasecki J, Bechtold D, Keane E, Jones M: Wounded spirits, ailing hearts: PTSD and related disorders among American Indians, in Ethnocultural Aspects of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Issues, Research, and Clinical Applications. Edited by Marsella AJ, Friedman MJ, Gerrity ET, Scurfield RM. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996, pp 255–283Google Scholar

24. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:771–788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Nelson SH, McCoy GF, Stetter M, Vanderwagen WC: An overview of mental health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 1990s. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:257–261Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Manson SM: Behavioral health services for American Indians: need, use, and barriers to effective care, in Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Edited by Dixon M, Roubideaux Y. Washington, DC, American Public Health Association, 2001, pp 167–192Google Scholar