Burdens and Benefits of Placebos in Antidepressant Clinical Trials: A Decision and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The use of placebos is a necessary, if controversial, part of determining the efficacy of new antidepressants in randomized clinical trials. Such studies need to convey accurate and useful risk-benefit information to subjects since effective treatments are withheld. The authors assessed the cost-effectiveness of entering such a trial from the perspective of potential subjects. METHOD: The choice between individualized psychiatric treatment and an 8-week placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial was modeled by using a static model. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of a potential subject who has moderate depression, is at low risk for suicide, has no comorbid conditions, and lacks adequate insurance to pay for mental health services. The trial was assumed to be free for subjects, except for indirect costs. Model outcomes included the probability of treatment response at 8 weeks and “decremental” cost-effectiveness. Data were based on reviews of published and some unpublished clinical trials of novel antidepressants that were eventually shown to be efficacious. RESULTS: A participant in a typical antidepressant efficacy trial has a chance of treatment response almost 25% less than that with individualized treatment. An uninsured participant can expect to save just over $164 for every 10% chance of response sacrificed by entering the placebo-controlled trial. CONCLUSIONS: For placebo-controlled antidepressant trials, it is possible to derive systematic and evidence-based estimates of the burdens and potential benefits to subjects. Such information may be more useful for institutional review boards and potential subjects than an unstructured enumeration of risks and benefits.

Placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials testing novel antidepressants are receiving considerable attention because of the inherent ethical tension in using placebos when effective treatments exist (1–3). Despite heated debate, most countries permit placebos in such contexts as long as the research is approved by a research ethics committee, informed consent is obtained from the participants, and the risks and burdens to the subjects are not excessive (3, 4). Excessive risks and burdens are usually defined as an increased risk of death or permanent injury due to the use of placebo (4, 5), although other additional safeguards have been proposed (2).

The debate over the ethics of using placebo controls in place of proven treatments has focused exclusively on the permissibility of such trials (1, 2, 5, 6). But a related ethical issue has received little attention, viz., the special burdens created for the informed consent process for such clinical trials. Given the potential for a lower expected health benefit from opting for a randomized controlled trial rather than individualized treatment and given the apparent tendency of research participants to enroll out of self-interest (7), it is important to help potential participants avoid the therapeutic misconception (8) that entering the trial has more expected health benefit than it actually has.

While it is important to enumerate the risks and potential benefits as well as to mention the option of receiving individualized treatment, a mere enumeration without an objective comparison of the two options may not be enough. We derive here one type of comparative information that balances the burdens and benefits of individualized treatment against those of a randomized controlled trial. It may be of interest to potential participants, research ethics committees, investigators, and other parties with a stake in ensuring a valid informed consent process for such clinical trials.

Method

Type of Analysis

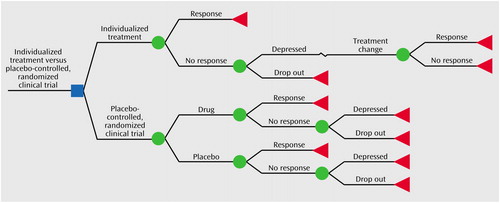

We performed a cost-effectiveness analysis using decision-analytic modeling to compare two options: receiving routine individualized psychiatric treatment (status quo strategy) and participating in a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of a new antidepressant (alternative option), as shown in Figure 1 (generated by using Data 4.0 from TreeAge Software, Williamstown, Mass.).

Since the decision is one made by potential subjects, the analysis was performed from their perspective.

Target Population

We considered persons who are typically approached for randomized clinical trials of antidepressants: in early middle age (40s), predominantly female, with moderate depression (mean baseline score of 22 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) and no significant comorbid conditions (9). While this group does not reflect the general clinical population of persons with major depression (10), this restriction is appropriate for the ethical question at issue. In addition, the potential participants were assumed to lack insurance coverage for mental health services and medications.

Time Horizon and Boundaries

We restricted the outcome of interest to a question that we felt would be meaningful to potential participants: “How much worse (or better) off would I be in terms of meaningful improvement in my condition by the end of the randomized clinical trial if I choose to enroll in the trial, instead of receiving individualized psychiatric treatment—and at what savings (or cost)?” We chose a trial of 8 weeks’ duration to define the time horizon. We did not consider the major complication of depression, suicide, because there appear to be no differences in the rates of suicide and suicidal ideation between placebo conditions and drug conditions and because the estimates of suicide and suicidal ideation in persons in depression trials fall within the range estimated outside the context of randomized clinical trials (11, 12). Indeed, under current regulatory guidelines, if there was a clinically meaningful increase in the suicide rate attributable to the use of placebos, then such clinical trials would be banned and the present analysis would be unnecessary. Other longer-term effects (e.g., effect of delayed treatment on long-term outcome) are ignored, as there are few data regarding this issue.

Status Quo Strategy

The individualized treatment option assumes 8 weeks of pharmacotherapy. There is one 1-hour initial diagnostic evaluation followed by three 20–30-minute maintenance visits. If the initial strategy fails, two more maintenance visits are required and the psychiatrist will try an alternative medication strategy. Patients who drop out are assumed to do so on average after three visits.

The outcome of interest is the likelihood of a substantial improvement in symptoms. We used the most widely used definition of “response” in randomized clinical trials, i.e., greater than 50% improvement in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score (13, 14). This correlates fairly well with global rating scales akin to what a clinician might find useful (9).

The efficacy assumptions for the base case are listed in Table 1. A wide range of response rates are reported. While some cost-effectiveness analyses of the treatment of depression in the primary care context used a response rate close to 90% (15, 16), we adopted a more conservative estimate based on both our clinical judgment and the literature (14, 17). The response rate for individualized treatment is assumed to be 50% for the initial strategy (14) and a 50% success rate for treatment of the initial nonresponders who do not drop out (18).

The dropout rates are modeled in the decision tree as conditional on nonresponse. This is a simplification as it is likely that some persons who respond to an antidepressant will drop out because of side effects. We could not find reliable data on this. What exists are data on dropouts according to assigned groups in randomized clinical trials (9, 11, 13). It was reasoned that a person in individualized treatment who does not respond to an initial medication will be less likely to drop out (conditional probability of 0.4) than a nonresponder in a randomized clinical trial (conditional probability of 0.6). The overall dropout rates for both clinical trials and individualized treatment are based on published data (9, 11, 14).

Alternative Option

In the randomized clinical trial option, it is assumed that a fixed dose or doses will be used throughout the trial and that the subjects cannot leave and enter another treatment group as an adjustment to clinical response. There is a 50% chance of receiving the placebo. There is an initial 2-hour visit followed by seven more 1-hour visits, unless a person drops out. Patients who drop out are assumed to do so on average after three visits.

A key assumption in the base case is that the response rate for subjects who receive the study drug in the randomized clinical trial is the average of the response rates across published reports of studies of antidepressants known to be effective. Thus, it is assumed that the clinical trial at issue will show a significant advantage of the study drug over placebo, with response rates of 49% for the study drug and 30% for placebo (9). While the rates of response to placebo might be higher in unpublished, “failed” studies (19), our estimate is supported when both published and unpublished studies of an efficacious drug are taken into account (11, 13).

Estimating Costs

Table 1 provides a summary of cost estimates, given in 2002 U.S. dollars. Time off from work includes both the appointment duration and one additional hour per visit to account for travel. The fee schedule for psychiatric visits was taken from the sliding scale of the University of Rochester’s Strong Behavioral Health outpatient department, and it is appropriate for a person earning $10/hour (annual income, $18,000 to $21,000). The cost of the drug for individualized treatment was derived from the actual cost to patients at Strong Behavioral Health pharmacy. An initial treatment failure leads to a 50% increase in medication cost (either because the dose must be increased or because an entirely new prescription is needed and it may overlap for some time with the initial drug because of tapering). All components of the clinical trial are assumed to be free, except for the cost incurred in being away from work. Given the study boundaries and time horizon, no discounting or adjustments for inflation are needed.

Analysis

To analyze the difference in effectiveness between the two alternatives, we adapted concepts used in evidence-based medicine (20), as follows. We calculated the absolute benefit decrease as the arithmetic difference in therapeutic response between the two strategies and the relative benefit decrease as the proportional decrease in response rate from choosing the randomized clinical trial over individualized treatment. Finally, we defined and calculated the number of study subjects that need to be enrolled to prevent one clinical trial subject from responding to treatment because he or she chose the clinical trial over individualized treatment, and we defined that number as the reciprocal of the absolute benefit decrease.

We also calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness of the clinical trial in relation to individualized treatment; this was defined as the additional cost (or savings) involved in increasing (or decreasing) the probability of achieving a therapeutic response. In situations where the probability of achieving a therapeutic benefit is less in the alternative strategy and less costly than in the status quo strategy, we use the term “decremental cost-effectiveness ratio.”

Results

Effectiveness and Costs

A summary of the cost-effectiveness analysis for the base case is presented in Table 2. The individualized treatment yields a 64% response rate, while the placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial yields a 40% response rate. The absolute benefit decrease for a subject entering the clinical trial is therefore 24%. The relative decrease in benefit is 38% (24%/64%). The number of subjects needed to result in one person not responding to treatment because he or she chose the randomized clinical trial over individualized treatment is approximately four (1/0.24).

The expected cost of individualized treatment for 8 weeks is $542, while the expected cost of participating in a clinical trial is $134. The decrease in cost from choosing the clinical trial is $408.

For every 1% chance of treatment response sacrificed in forgoing individualized treatment and instead entering the randomized clinical trial, there is a $16.45 savings to the subject. Thus, for every 10% chance of response sacrificed, our subject would gain about $165.

Sensitivity Analyses

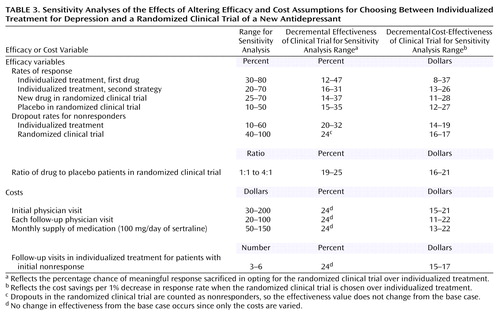

In decision and cost-effectiveness analyses such as this, it is important to assess the effect of various assumptions made in the model (21, p. 31). The one-way sensitivity analyses for the decremental cost-effectiveness and for the decremental effectiveness are presented in Table 3 for 11 selected estimates of the model. In general, the model is fairly robust to changes in model estimates. For example, when the placebo response rate is assumed to be 50% rather than 30%, the efficacy advantage of individualized treatment decreases but is still 15%; the cost savings from each 1% chance of response sacrificed consequently goes up from about $16 to $27. The sensitivity analyses favor the individualized treatment option at all points for all one-way analyses.

What would happen if more than one variable at a time is examined? A two-way analysis (i.e., estimates when two variables are varied simultaneously) of the rates of response to placebo and drug in the randomized clinical trial showed that even if the placebo response is 50% and the drug response rate is 70%, individualized treatment would still have a 4% expected advantage in response rate. At the other extreme, if the placebo and drug response rates are 10% and 25%, respectively, individualized treatment would have a 46% efficacy advantage. While these estimates at the extremes are unlikely to occur, they serve to frame the range of possible outcomes.

Discussion

The purpose of this analysis was to quantify the tradeoffs faced by a potential research participant as he or she contemplates entering a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial rather than individualized treatment for the treatment of major depression. If the potential subject is primarily seeking rapid and meaningful improvement in his or her depression, the clinical trial should not be chosen since doing so involves giving up 24% of the chance of treatment response. This confirms one of the recommendations of an important consensus panel (1). Further, sensitivity analyses reveal that for every one-way analysis, the superior effectiveness of individualized treatment is maintained at all points. This is true even if the exposure to placebo is minimized by increasing the ratio of drug to placebo subjects in the clinical trial to 4:1. However, if the subject is willing to trade off treatment response in order to save money, then he or she would save $408 by giving up 24% of the chance of response by entering the randomized clinical trial.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are, first, we did not address other factors that may go into a potential participant’s decision to enter a clinical trial. These include open-label extensions with free maintenance medication, financial incentives for participation, and altruistic motives for participation. However, the effectiveness analysis clarifies how strong a motive these other considerations have to be in order to outweigh the loss in chance for treatment response. Second, the quality of the data for the clinical trial option is based on several meta-analyses and is relatively high. The quality of the data for individualized treatment, however, involves clinical judgment. It is inherently difficult to estimate treatment responses for a group of patients that constitute only a minority of a general psychiatric clinic’s population, since efficacy trials involve such atypical patients (10). The cost estimates for the base case are also limited. Since there are no data on the insurance status of actual participants in clinical trials of antidepressants, the assumption of a lack of insurance for our base case is best seen as an illustrative exercise. Third, the base case assumes that the experimental drug at issue will turn out to have significant efficacy advantage over placebo. Since not all attempts to receive marketing approval succeed and since about half the trials of effective antidepressants fail to show a significant difference from placebo (3), this is an assumption clearly in favor of randomized clinical trials. Finally, every model is only as good as its assumptions. While we believe the estimates for the base case analysis are reasonable, we provide an extensive sensitivity analysis in Table 3 so that the reader can assess the effects of varying the assumptions used in this model.

Policy Implications and Future Studies

It is possible to derive clear, quantitative conclusions about the risks and potential benefits of participating in placebo-controlled clinical trials that withhold effective treatments. One useful metric is the number of subjects needed in such a randomized clinical trial before one subject fails to respond to treatment as a result of enrolling in the clinical trial rather than receiving individualized treatment. It seems important information for subjects or members of research review committees to know that one in four persons in a randomized clinical trial will fail to experience meaningful improvement in symptoms because of the withholding of treatment that is necessary for research. Such information may be more useful and thus more ethically appropriate than the laundry list of potential risks and benefits usually given to research subjects. Further studies may determine whether such information is acceptable and desired by subjects, whether it decreases the therapeutic misconception, and how it affects recruitment.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 24th annual meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making, Baltimore, Oct. 19–23, 2002. Received Sept. 5, 2002; revision received Dec. 27, 2002; accepted Jan. 10, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, the Program in Clinical Ethics, the Department of Neurology, and the Department of Community and Preventive Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kim, Box PSYCH, 300 Crittenden Blvd., Rochester, NY 14642; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Career Development Award MH-64172 to Dr. Kim from NIMH and by Mid-Career Investigator Award NS-42098 to Dr. Holloway from the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke.

Figure 1. Decision Tree for Choosing Between Individualized Treatment for Depression and a Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of a New Antidepressant

1. Charney DS, Nemeroff CB, Lewis L, Laden S, Gorman J, Laska E, Borenstein M, Bowden C, Caplan A, Emslie G, Evans D, Geller B, Grabowski L, Herson J, Kalin N, Keck PE, Kirsch I, Krishnan KRR, Kupfer D, Makuch R, Miller FG, Pardes H, Post R, Reynolds M, Roberts L, Rosenbaum J, Rosenstein D, Rubinow D, Rush A, Ryan N, Sachs G, Schatzberg A, Solomon S (Consensus Development Panel): National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the use of placebo in clinical trials of mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:262-270Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Emanuel EJ, Miller FG: The ethics of placebo-controlled trials—a middle ground. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:915-919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Laughren TP: The scientific and ethical basis for placebo-controlled trials in depression and schizophrenia: an FDA perspective. Eur Psychiatry 2001; 16:418-423Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Food and Drug Administration: International Conference on Harmonization: choice of control group in clinical trials. Federal Register 1999; 64:51767-51780Google Scholar

5. Temple R, Ellenberg S: Placebo-controlled trials and active-control trials in the evaluation of new treatments. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133:455-463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Freedman B, Weijer C, Glass KC: Placebo orthodoxy in clinical research, I: empirical and methodological myths. J Law Med Ethics 1996; 24:243-251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Edwards SJL, Lilford RJ, Hewison J: The ethics of randomised controlled trials from the perspectives of patients, the public, and healthcare professionals. Br Med J 1998; 317:1209-1212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz CW, Benson P, Winslade W: False hopes and best data: consent to research and the therapeutic misconception. Hastings Cent Rep 1987; 17:20-24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M: Placebo response in studies of major depression. JAMA 2002; 287:1840-1847Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI, Posternak MA: Are subjects in pharmacological treatment trials of depression representative of patients in routine clinical practice? Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:469-473Link, Google Scholar

11. Khan A, Warner H, Brown W: Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:311-317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Storosum JG, van Zwieten BJ, van den Brink W, Gersons BPR, Broekmans AW: Suicide risk in placebo-controlled studies of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1271-1275Link, Google Scholar

13. Bech P, Cialdella P, Haugh MC, Birkett MA, Hours A, Boissel JP, Tollefson GD: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine v placebo and tricyclic antidepressants in the short-term treatment of major depression. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:421-428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Nierenberg AA, Farabaugh AH, Alpert JE, Gordon J, Worthington JJ, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M: Timing of onset of antidepressant response with fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1423-1428Link, Google Scholar

15. Revicki D, Brown R, Keller M: Cost-effectiveness of newer antidepressants compared with tricyclic antidepressants in managed care settings. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:47-58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Revicki D, Brown R, Palmer W, Bakish D, Rosser W, Anton S, Feeny D: Modelling the cost-effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Pharmacoeconomics 1995; 8:524-540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Normand SL, Frank RG, McGuire TG: Using elicitation techniques to estimate the value of ambulatory treatments for major depression. Med Decis Making 2002; 22:245-261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Thase ME, Blomgren S, Birkett M, Apter J, Tepner R: Fluoxetine treatment of patients with major depressive disorder who failed initial treatment with sertraline. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:16-21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Otto M, Nierenberg A: Assay sensitivity, failed clinical trials, and the conduct of science. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71:241-243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sackett DL, Straus S, Richardson S, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB: Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 2000Google Scholar

21. Petitti DB: Meta-Analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Methods for Quantitative Synthesis in Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2000Google Scholar