Olanzapine Versus Divalproex Sodium for the Treatment of Acute Mania and Maintenance of Remission: A 47-Week Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Few double-blind trials have compared longer-term efficacy and safety of medications for bipolar disorder. The authors report a 47-week comparison of olanzapine and divalproex. METHOD: This 47-week, randomized, double-blind study compared flexibly dosed olanzapine (5–20 mg/day) to divalproex (500–2500 mg/day) for manic or mixed episodes of bipolar disorder (N=251). The only other psychoactive medication allowed was lorazepam for agitation. The primary efficacy instrument was the Young Mania Rating Scale; a priori protocol-defined threshold scores were ≥20 for inclusion, ≤12 for remission, and ≥15 for relapse. Analytical techniques included mixed model repeated-measures analysis of variance for change from baseline, Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) for categorical comparisons, and Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to events of interest. RESULTS: Over 47 weeks, mean improvement in Young Mania Rating Scale score was significantly greater for the olanzapine group. Median time to symptomatic mania remission was significantly shorter for olanzapine, 14 days, than for divalproex, 62 days. There were no significant differences between treatments in the rates of symptomatic mania remission over the 47 weeks (56.8% and 45.5%, respectively) and subsequent relapse into mania or depression (42.3% and 56.5%). Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring significantly more frequently during olanzapine treatment were somnolence, dry mouth, increased appetite, weight gain, akathisia, and high alanine aminotransferase levels; those for divalproex were nausea and nervousness. CONCLUSIONS: In this 47-week study of acute bipolar mania, symptomatic remission occurred sooner and overall mania improvement was greater for olanzapine than for divalproex, but rates of bipolar relapse did not differ.

Rapid resolution of acute mania can reduce the substantial personal and economic burdens on patients, their families, and society (1, 2). Most controlled clinical trials of pharmacological treatment for bipolar mania focus on short-term improvement, collecting data for only 3–6 weeks. However, studies of the acute phase are limited in that they do not help determine longer-term efficacy and stability of course. Examining data from only the first few weeks of medication use may lead to incorrectly concluding that medications with more rapid onset of action are more efficacious than those with slower onset (3). Also important, longer-term studies allow better assessment of whether and how quickly patients reach endpoints such as full syndromal remission, which are difficult to achieve in short-term studies (2, 4).

Prospective follow-up of bipolar patients has shown that the mean time to syndromal remission is approximately 6 weeks for first manic episodes. In some patients, remission may take longer (4). In a naturalistic study (4), we found that 50.0% of first-episode patients experienced syndromal remission of psychotic mania in 5.9 weeks, but there was considerable variability. At 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, 65.1%, 83.7%, 91.1%, and 97.5% of patients achieved syndromal remission, respectively. When other definitions of remission are used, the time to remission varies further. Similar rates were found in another study of first-episode bipolar illness conducted at the University of Cincinnati (5). However, as a history of previous episodes of bipolar disorder is a strong predictor of relapse (6, 7), the outcome after the first episode may differ from the outcome after multiple episodes (2).

Both divalproex (8, 9) and olanzapine (10, 11) have been shown to be efficacious in acute mania, each in two double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials. In addition, longer-term treatment with divalproex was studied in one published double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial (12). The lack of longer-term studies is not unusual, as there have been few trials with other medications for the maintenance of bipolar disorder (13–15).

We previously reported (16) results from a 3-week study assessing the safety and efficacy of olanzapine compared with divalproex for patients with a diagnosis of bipolar mania. Patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with either olanzapine (5–20 mg/day) or divalproex (500–2500 mg/day, recommended therapeutic serum level of 50–125 μg/ml). After this initial period, the patients entered a 44-week, double-blind extension period, in which they remained in the same treatment group. We reported that olanzapine-treated patients had significantly greater improvement as shown by the Young Mania Rating Scale (17) and that the proportion of these patients who achieved protocol-defined remission was greater than that for the divalproex-treated patients. In this article we focus on improvement of mania symptoms, remission rates, time to response, and relapse rates over the entire 47-week treatment period.

Method

Study Design

The 251 patients were ages 18–75 years and met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a manic or mixed episode of bipolar disorder, as determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Version (18). A baseline total score of at least 20 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (17) was required for study entry. Female patients of childbearing potential were required to use a medically accepted means of contraception. Any of the following was considered grounds for exclusion: serious and unstable medical illness; DSM-IV substance dependence within the past 30 days (except nicotine or caffeine); documented history of intolerance to olanzapine or divalproex; treatment with lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic medication within 24 hours of randomization; treatment with clozapine within 4 weeks of randomization; and serious suicidal risk. The study was powered to assess efficacy at 3 weeks; the primary outcome measure was the Young Mania Rating Scale.

The protocol was reviewed and approved by local institutional review boards at each of the 44 study sites in the United States before enrollment of any patients. After the study was thoroughly explained, each patient signed written, informed consent. Patients remained inpatients for at least the first week of double-blind treatment.

The initial dose of olanzapine was 15 mg/day, and for divalproex it was 750 mg/day, consistent with the manufacturers’ recommendations (19). The investigators made dose adjustments based primarily on clinical response but also on serum concentrations and adverse events. Patients who did not tolerate the minimum treatment dose (5 mg/day of olanzapine or 500 mg/day of divalproex) were removed from the study.

Serum concentrations were measured to evaluate whether divalproex trough levels were maintained within the targeted therapeutic range of 50–125 μg/ml. To maintain the blind, blood was also drawn from all subjects randomly assigned to olanzapine, and sham “divalproex” results were reported, as we will describe. All investigators at the clinical sites and at Lilly Research Laboratories were kept blinded to treatment assignment. Blood was drawn from all patients periodically during the study. The samples were shipped to an independent reference laboratory; a coordinator at the reference laboratory was unblinded to treatment assignment. Divalproex concentrations below 35 μg/ml were reported as “well below target level,” those from 35 to 49 μg/ml were reported as “below target level,” those from 126 to 150 μg/ml were reported as “above target level,” and those above 150 μg/ml were reported as “well above target level.” If a serum level was found to be above or below the therapeutic range, the divalproex dose was modified accordingly such that the serum level was brought back to the therapeutic range within 30 days. For each report of a serum level out of the target range that was sent for a divalproex-treated patient, a similar sham out-of-target-range report for divalproex was sent for a randomly selected olanzapine-treated patient at a different investigative site. If the investigator decided to change the medication dose on the basis of the sham divalproex serum level for a patient taking olanzapine, the increase or decrease affected only the number of placebo tablets given to that patient. This method ensured maintenance of the blind procedure.

Concomitant lorazepam was allowed throughout the 47 weeks, but use was restricted to a maximum dose of 2 mg/day, and it was not allowed within 8 hours of the administration of a symptom rating scale. Benztropine was permitted to treat extrapyramidal symptoms, up to a maximum of 6 mg/day. Throughout the study, benztropine was not allowed as prophylaxis for extrapyramidal symptoms.

Assessment

Severity of symptoms was assessed with the 11-item Young Mania Rating Scale (17), the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (20), the severity of illness rating from the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for bipolar disorder (21), and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (22). These were administered daily during the first week, weekly from weeks 1 to 5, biweekly from weeks 5 to 11, monthly from weeks 11 to 23, and bimonthly from weeks 23 to 47. The a priori categorical definitions included the following. Symptomatic remission of mania was defined as an endpoint total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale of ≤12. Symptomatic remission of mania and depression was defined as an endpoint total mania score of ≤12 and a Hamilton depression scale score of ≤8. Syndromal remission of mania was defined on the basis of DSM-IV criteria as having no A criterion worse than mild in severity and no more than two B criteria rated as mild in severity, as previously defined in the literature (4, 5, 23). Syndromal remission of mania and depression was defined as the preceding mania criteria plus the following depression criteria: no DSM-IV A criteria for a major depressive episode that were worse than mild in severity and the presence of no more than three A criteria rated as mild, as previously suggested by Frank et al. (24). Symptomatic relapse into an affective episode (depression, mania, or mixed) was defined as a mania score of ≥15 or a depression score of ≥15 in a patient who previously met the criteria for symptomatic remission. Syndromal relapse into an affective episode was defined as achievement of syndromal remission according to both mania and depression criteria followed by relapse into either mania or depression. Time to remission was determined on the basis of when the patient first met the criteria for remission. Time to relapse was computed by prospectively examining the data for the patients who met the criteria for remission at week 3. Safety was monitored by assessing adverse events, laboratory values, ECGs, vital signs, weight change, and extrapyramidal symptoms, measured with the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (25), Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia (26), and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (27). Adverse events that originally occurred or worsened during double-blind therapy were considered treatment emergent and were recorded and coded by using the Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms (COSTART) dictionary (28).

Statistical Methods

Patient data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. Patients with a baseline and at least one postbaseline measurement were included in the analysis. Total scores were derived from the individual items; if any single item was missing, the total score was treated as missing. Analyses of change from baseline in the efficacy measures were conducted by using a mixed model repeated-measures analysis of variance (MMRM) with visit, treatment, investigator, and visit-by-treatment interaction as effects in the model and with the corresponding baseline score and the interaction between baseline score and visit included as covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was fit to the within-patient repeated measures. The main overall effect of treatment was assessed, as well as the difference between treatment groups in change from baseline to each visit, by using contrasts within the repeated-measures model. As an additional analysis, mean change from baseline to endpoint, with the last observation carried forward, was examined by using ANOVA with treatment and investigator in the model. Rates were compared in the two groups by using Fisher’s exact test. Time to symptomatic and syndromal remission of mania only and to both mania and depression and time to symptomatic and syndromal recurrence of mania and depression were analyzed by using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and the curves were compared by using the log-rank test. Time to discontinuation was analyzed in a similar fashion. Treatment-emergent adverse events (based on COSTART terms) and rates of treatment-emergent abnormally high or low laboratory values and vital signs were compared with Fisher’s exact test. Weight, laboratory values, and extrapyramidal symptom ratings were analyzed by using mean change from baseline to endpoint (last observation carried forward) in an ANOVA with treatment and investigator in the model. In addition, the percentages of patients gaining at least 7% of baseline body weight (last observation carried forward) were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. All p values were based on two-tailed tests with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 251 patients across 44 sites in the United States were enrolled in the study, of whom 125 were randomly assigned to olanzapine and 126 were assigned to divalproex. The patients had a mean age of 41 years (range=18–75), 57.4% were female, and 80.9% were Caucasian. The mean duration of illness was 18.2 years (SD=12.2), and the current episode had lasted for a mean of 47.8 days (SD=57.1). Overall, the patients experienced clinically severe symptoms, and their mean Young Mania Rating Scale total score was 27.7 (SD=5.9). There was no significant difference between groups in any demographic or baseline characteristic.

The disposition of the patients is shown in Table 2. A total of 125 olanzapine-treated patients and 123 divalproex-treated patients had at least one postbaseline measurement and were included in the analysis. Patients in remission at week 3 were more likely to complete the 47-week trial (12 [20.3%] of 59 olanzapine-treated patients and 11 [26.2%] of 42 divalproex-treated patients) than those not in remission (seven [10.6%] of 66 olanzapine-treated and nine [11.1%] of 81 divalproex-treated patients) (p=0.01, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by treatment). The numbers of subjects were 91 for olanzapine and 89 for divalproex at week 3, 46 for olanzapine and 44 for divalproex at week 15, and 19 for olanzapine and 20 for divalproex at week 47. The median time to discontinuation was 62 days for the olanzapine group and 49 days for the divalproex group (log rank χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.93).

There was no difference between groups in compliance. The patients were highly compliant with study medication, as assessed by pill counts (90.6% for olanzapine and 89.9% for divalproex). The mean modal dose for the olanzapine-treated patients was 16.2 mg/day (SD=4.9), and the mean modal dose for the divalproex-treated patients was 1584.7 mg/day (SD=618.1). The mean valproate blood levels after 3, 7, 11, and 47 weeks of treatment were 83.9 μg/ml (SD=32.1), 72.5 μg/ml (SD=33.6), 64.1 μg/ml (SD=34.3), and 58.2 μg/ml (SD=30.8), respectively. The percentages of patients with blood levels of 50 μg/ml or higher were 88.3%, 78.1%, 71.4%, and 61.9%, respectively, after 3, 7, 11, and 47 weeks of treatment. The mean daily doses were 1554.1 mg (SD=491.4) at week 3, 1708.0 mg (SD=541.5) at week 7, 1716.8 mg (SD=517.1) at week 11, and 1500.5 mg (SD=579.7) at week 47.

Efficacy

Rating scale scores

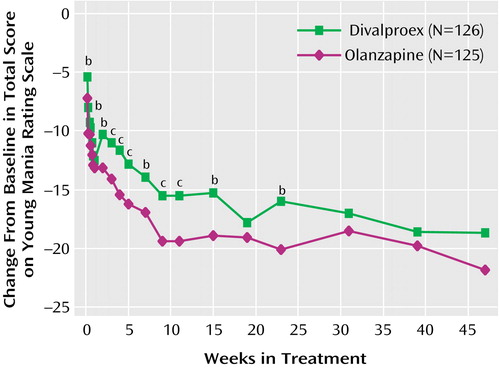

Differences in the total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale were examined by using an MMRM. The olanzapine-treated patients experienced a significantly greater reduction in least-squares mean score than the divalproex-treated patients; the difference between groups in the reduction averaged 2.38 points (SE=0.76) over the trial (F=9.77, df=1, 88, p=0.002). The improvement with olanzapine was significantly superior at all visits between weeks 2 and 15, inclusive, and at week 23 (Figure 1). However, the differences in improvement narrowed later in the study, and there were no significant differences between treatments from week 30 to week 47. An analysis of the change from baseline to endpoint (last observation carried forward up to week 47) detected a statistically significant difference between the groups (olanzapine: mean=–15.38, SD=10.17; divalproex: mean=–12.50, SD=11.51) (F=5.43, df=1, 218, p=0.03).

In the MMRM, the improvement in mean Hamilton depression score for the olanzapine-treated patients was greater by 1.19 points (SE=0.65) than that of the divalproex-treated patients, but the difference was not statistically significant (F=3.39, df=1, 107, p=0.07). An analysis of the change from baseline to endpoint in the Hamilton depression scale score, with the last observation carried forward, indicated no significant difference between groups (olanzapine: mean=–3.78, SD=8.92; divalproex: mean=–1.59, SD=8.22) (F=3.25, df=1, 216, p=0.08).

No significant differences between groups were found in the total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale according to MMRM (F=0.07, df=1, 106, p=0.80) or change from baseline to endpoint with the last observation carried forward (olanzapine: mean=–12.11, SD=19.69; divalproex: mean=–8.87, SD=19.36) (F=1.37, df=1, 216, p=0.25). No significant differences between groups were found in the CGI severity of illness with MMRM (F=2.59, df=1, 119, p=0.11) or the change from baseline to endpoint with the last observation carried forward (olanzapine: mean=–1.98, SD=1.42; divalproex: mean=–1.70, SD=1.53) (F=3.58, df=1, 217, p=0.06).

Symptomatic and syndromal remission of mania

The median time to symptomatic remission of mania (defined as a score of 12 or less on the Young Mania Rating Scale) was significantly shorter for the olanzapine-treated patients (14 days) than for those treated with divalproex (62 days) (log rank χ2=3.96, df=1, p=0.05). At 47 weeks (last observation carried forward), the rates of symptomatic mania remission were 56.8% and 45.5% for the olanzapine and divalproex groups, respectively (Fisher’s exact p=0.10).

The median times to syndromal remission of mania were 28 and 109 days for the olanzapine- and divalproex-treated groups, respectively (log rank χ2=6.63, df=1, p=0.01). The syndromal remission rates at 47 weeks were 50.8% for olanzapine versus 38.2% for divalproex (Fisher’s exact p=0.06).

Symptomatic and syndromal remission of both mania and depression

The times to symptomatic remission of mania and depression were similar for olanzapine (25th percentile=14 days) and divalproex (25th precentile=13 days) (χ2=0.03, df=1, p=0.86). At 47 weeks (last observation carried forward), the rates of symptomatic remission of both mania and depression were 30.9% for both the olanzapine and divalproex groups (Fisher’s exact p=1.00).

The times to syndromal remission of both mania and depression did not differ significantly between groups: the 25th percentile was 7 days for olanzapine and 34 days for divalproex (χ2=0.25, df=1, p=0.62). Likewise, the rates of syndromal remission at 47 weeks were similar: 29.8% for olanzapine and 27.6% for divalproex (Fisher’s exact p=0.78).

Symptomatic recurrence of any affective episode

There was no statistically significant difference in time to symptomatic recurrence of an affective episode (depression, mania, or mixed) between the olanzapine- and divalproex-treated groups (χ2=0.22, df=1, p=0.64) (25th percentile for both groups=27 days). Symptomatic recurrence of an affective episode occurred in 14 (42.4%) of 33 olanzapine-treated patients and 13 (56.5%) of 23 divalproex-treated patients (Fisher’s exact p=0.42). Of the 14 olanzapine-treated patients experiencing recurrence, eight experienced depression, five experienced mania, and one experienced a mixed episode. Of the 13 divalproex-treated patients experiencing recurrence, six experienced depression, four experienced mania, and three experienced mixed episodes.

Syndromal recurrence of any affective episode

There was no statistically significant difference in the times to syndromal recurrence of an affective episode between the olanzapine- and divalproex-treated groups (χ2=0.70, df=1, p=0.41) (the medians for olanzapine and divalproex were 14 and 42 days, respectively). Syndromal recurrence of an affective episode occurred in 20 (64.5%) of 31 olanzapine-treated patients and 13 (65.0%) of 20 divalproex-treated patients (Fisher’s exact p=1.00).

Relation of valproate serum concentration to outcome

In an examination of patients whose valproate concentrations were measured at 3 weeks, a median split of patients by valproate concentration (valproate measurements were available for 77 patients; median concentration=82 μg/ml) showed no difference in the percentage of patients in remission at week 3 (last observation carried forward analysis). Of the 38 patients with “high” concentrations (above 82 μg/ml), 42.1% (N=16) were in remission compared to 38.5% (N=15) of the 39 patients with “low” concentrations (less than or equal to 82 μg/ml) (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.82). Similarly, there was no difference in the remission rates at endpoint (last observation carried forward up to week 47) between the patients with high concentrations (57.9%, N=22) and those with low concentrations (56.4%, N=22) (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00). In an examination of completion rates, there was again no significant difference between the patients with high concentrations (21.1%, N=8) and those with low concentrations (25.6%, N=10) (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.79).

A secondary analysis was also conducted to compare the remission rate of the olanzapine-treated patients to that of the only 91 (of 123) divalproex-treated patients with valproate blood levels at or above the therapeutic range (≥50 μg/ml) at week 1 of treatment. Fourteen patients were dropped from this analysis because their blood levels were below 50 μg/ml, and for 18 patients valproate levels were not measured at week 1. The rates of symptomatic remission of mania at week 47 (last observation carried forward) were 56.8% and 51.6% for the olanzapine- and divalproex-treated patients, respectively (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.49). The median time to symptomatic mania remission was 27 days for the divalproex patients with therapeutic blood concentrations, compared to the 14 days for olanzapine (log rank χ2=2.43, df=1, p=0.12). For syndromic remission of mania at week 47 (last observation carried forward), 44.0% of divalproex-treated patients met the criteria compared to 50.8% of olanzapine-treated patients (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.34). The median time to remission remained 28 days for olanzapine and 109 days for divalproex (log rank χ2=4.66, df=1, p=0.04).

Finally, the total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale and the improvement from baseline in patients with valproate blood concentrations less than 50 μg/ml at week 3, 7, 11, or 47 did not significantly differ from those of the patients with valproate blood concentrations of 50 μg/ml or higher. In fact, at three of the four assessments (weeks 3, 7, and 47), the results were numerically better in the group with concentrations below 50 μg/ml.

Safety

A total of 31 (24.8%) of the 125 olanzapine patients and 25 (19.8%) of the 126 divalproex patients discontinued study participation because of an adverse event (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.37). Treatment-emergent adverse events (as reported by the investigator) occurring more frequently during treatment with olanzapine (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.05) were somnolence, dry mouth, increased appetite, weight gain, akathisia, and elevated liver function test results (alanine aminotransferase). Among the patients receiving divalproex, nausea, nervousness, rectal disorder, and manic reaction were more common (p<0.05). While the COSTART term “manic reaction” was listed significantly more often for divalproex- than olanzapine-treated patients, this occurrence likely is related to efficacy rather than being an adverse event. Table 3 shows adverse events that were statistically different between groups or occurred in at least 10% of the patients in either treatment group. For treatment-emergent abnormally high laboratory values at endpoint, there was a statistically significant difference for alanine aminotransferase (5.1% for olanzapine versus 0.0% for divalproex) (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.03). There were two other significantly different treatment-emergent abnormally low laboratory values at endpoint: albumin (1.8% for olanzapine and 8.3% for divalproex) (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.04) and platelets (0.0% for olanzapine and 6.2% for divalproex) (Fisher’s exact p=0.007).

There were no significant differences between the olanzapine and divalproex groups in the mean change in extrapyramidal symptoms from baseline to endpoint, according to mean scores on the AIMS (–0.31 [SD=2.09] and –0.13 [SD=1.38] for olanzapine and divalproex, respectively) (F=0.87, df=1, 217, p=0.36), Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (0.16 [SD=2.17] and –0.31 [SD=2.44]) (F=2.39, df=1, 211, p=0.13), and Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia (–0.25 [SD=0.95] and –0.22 [SD=1.00]) (F=0.02, df=1, 211, p=0.89).

The patients in the olanzapine group had a significantly greater mean weight gain than those in the divalproex group according to an MMRM: 2.79 kg (SE=0.32) versus 1.22 kg (SE=0.32) (F=12.03, df=1, 127, p<0.001). Weight gain was significantly greater for the olanzapine patients from day 3 through week 15, inclusive; however, from weeks 19 through 47, there were no significant differences between groups in weight gain from baseline. Four olanzapine-treated patients dropped out because of weight gain, one each at weeks 3, 4, 19, and 39. At endpoint (last observation carried forward), 23.6% (N=29) of 123 olanzapine patients and 17.9% (N=22) of 123 divalproex patients had gained at least 7% of their baseline weight (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.35).

There was a significantly greater increase in cholesterol level among the olanzapine patients than among those treated with divalproex; the mean change from baseline to endpoint was 9.68 mg/dl for olanzapine (SD=34.13) and –2.33 mg/dl for divalproex (SD=32.73) (F=7.43, df=1, 205, p=0.007). There was no significant difference between groups in glucose concentration in a nonfasting state; the mean change from baseline to endpoint was 0.03 mmol/liter (SD=1.80) for olanzapine and –0.15 mmol/liter (SD=1.59) for divalproex (F=1.14, df=1, 205, p=0.29). The groups did not differ in the incidence of treatment-emergent abnormally high levels of cholesterol (olanzapine: one of 118, or 0.8%; divalproex: none of 115) (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00) or glucose (olanzapine: none of 113; divalproex: none of 114) (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00).

The mean change from baseline to endpoint in the Fridericia-corrected QT interval was 7.97 msec (SD=21.36) for 104 olanzapine-treated patients and –3.06 (SD=24.92) for 101 divalproex-treated patients (F=10.16, df=1, 175, p=0.002). We defined a potentially clinically significant change in QTc interval for men as from <430 msec at baseline to >430 at any point during the trial. For women we defined clinically significant change as an increase from <450 msec at baseline to >450 during the trial. Two (2.0%) of 102 olanzapine patients and two (2.1%) of 96 divalproex patients experienced such increases (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00). Across treatment groups, no man experienced a QTc higher than 450 msec and no women experienced a QTc higher than 470 msec, other common cutoffs reported in the literature.

Discussion

In this study we compared long-term improvement and maintenance of response over 47 weeks in patients with bipolar mania who received olanzapine and divalproex. We found that the rates of remission at endpoint were greater in both groups than at 3 weeks (16) and that olanzapine’s advantage fell short of statistical significance. However, symptomatic and syndromal remissions of mania were reached significantly sooner by the olanzapine-treated patients. It is interesting that, for both groups, symptomatic remission of mania occurred before the more conservative and clinically meaningful syndromal remission; the median times to syndromal remission were 28 days for olanzapine and 109 days for divalproex, whereas the times to symptomatic remission were 14 and 62 days, respectively. Shorter time to symptomatic remission has been previously reported in naturalistic studies (2, 4). There was no difference between groups in symptomatic or syndromal remission or recurrence of both mania and depression. The olanzapine-treated patients experienced greater improvement in mania ratings than the divalproex-treated patients; however, the mania ratings continued to improve in both groups over time. In a visit-by-visit analysis, the greatest between-group differences occurred in the first 15 weeks of treatment, and there were no significant differences between groups in improvement on the Young Mania Rating Scale from week 30 onward.

The study was designed to examine short-term and continued antimanic treatment effects, but it also allowed some exploration of relative efficacy for depressive symptoms and relapse prevention. Mean improvement in the score on the Hamilton depression scale was nonsignificantly greater for the olanzapine-treated patients. Interpretation of these findings is limited by the heterogeneity of the baseline Hamilton depression ratings (range=1–34) and variability in both groups over time. Comparative efficacy for relapse prevention would be better studied in a trial that starts with patients in stable remission. Several features of the current trial limit interpretation of the findings on relapse. For example, there are differences between the groups in the number of patients who achieved remission and the speed with which they did so. The time between ratings increased as the study progressed, such that relapse could be more efficiently captured and dated in earlier phases of the trial. The lengthening intervals between visits may have reduced overall clinical contact, perhaps contributing to patient dropout. The overall high dropout rate limits the power to detect differences in relapse. This trial failed to demonstrate a difference between treatments in time to relapse, but further study is warranted.

The mean valproate blood concentration in our study at 3 weeks was comparable to that reported by Bowden et al. (12) at 4 weeks: 83.9 versus 84.8 μg/ml, respectively. Findings on safety and tolerability were in accord with previously published findings for both agents (8, 9, 11, 12, 16, 29). The rates of study discontinuation for adverse events were similar for olanzapine and divalproex (24.8% and 19.8%, respectively). The most common adverse events for olanzapine were somnolence, depression, dry mouth, headache, weight gain, and asthenia. For divalproex, they were nausea, depression, headache, somnolence, nervousness, and pain. Weight gain was significantly greater for the olanzapine-treated patients. Generally, the courses of weight gain for the two medications appear to reflect those observed previously in different study groups. Patients with schizophrenia who gain weight while taking olanzapine are likely to have the most rapid increase in the first month, with stabilization late in the first year of treatment (30). Weight gain during treatment with divalproex appears to follow a more gradual pattern, such as that in a recently reported epilepsy clinical trial (31). Two laboratory measures increased more with olanzapine. First, the patients in that group had a greater mean increase in cholesterol. The second increased laboratory measure was alanine aminotransferase. This increase in the olanzapine-treated patients in this trial has been seen in other studies (32); it is typically observed early in treatment and is transient in nature.

A significant difference was found between the QTc intervals of the olanzapine- and divalproex-treated patients. The observed increase in the olanzapine-treated patients (7.97 msec) was greater than in other clinical trials (33, 34). The divalproex-treated patients had a mean QTc decrease of 3.06 msec. However, this difference is of unclear clinical significance because the treatment groups did not differ in the frequency of treatment-emergent QTc intervals greater than clinically important cutoffs.

There are limitations in the present study. First, dosing was adjusted at the discretion of the clinical investigator within large ranges (olanzapine: 5–20 mg/day; divalproex: 500–2500 mg/day) on the basis of response and tolerability. Therefore, it is likely that a proportion of divalproex patients had valproate blood concentrations below the therapeutic range at each visit. This proportion is probably higher than would have occurred if the study had compelled upward dose titration. Further, olanzapine was initially administered at 15 mg/day (a therapeutic dose for most patients), while divalproex was started at 750 mg/day (a subtherapeutic dose for most patients) with gradual titration upward. This dosing strategy followed the divalproex labeling instructions but may have given the olanzapine-treated group a slight early advantage in time to response. The flexible dosing scheme used in this study has the advantage of reflecting actual clinical practice, at least as represented by these investigators, but cannot directly address whether different dosing requirements might have changed the outcome; for instance, one previous divalproex trial (8) did apparently compel upward titration, if tolerated, even for patients with good clinical responses to lower doses. On the other hand, despite the differences in dosing, the two available comparisons of olanzapine and divalproex for acute mania (16, 29) show similar numeric differences between treatments in mean improvement on the 11-item Mania Rating Scale (29) or the 11-item Young Mania Rating Scale (16).

Second, the valproate concentrations were not reported as precise numbers but as broader ranges (e.g., “above target level” or “well above target level”). Because the study was blinded and included sham level reporting for the olanzapine-treated patients, this manner of reporting concentrations was not likely to have biased results, but it did limit the ability of the investigators to fine-tune their dosing and specifically may have decreased their comfort in prescribing doses that would result in blood levels above the target range as an attempt to maximize response. Late in the current study, the mean divalproex dose approached the lower end of the conventional range. It is possible that some patients at the lower end of the dose range may have been there because they were doing well and the physicians did not feel compelled to increase their doses. It is interesting that an analysis at week 3 showed no relationship between valproate blood concentration and either completion or remission. Further, no significant difference in mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale or in improvement from baseline was found between the divalproex patients with valproate blood concentrations below therapeutic levels and those with concentrations at or above those levels.

A third limitation of the study is that most of the patients withdrew from the study before completing 47 weeks of treatment. In fact, 31.2% of the olanzapine patients and 35.7% of the divalproex patients discontinued the study during the initial 3-week phase; of those entering the 44-week maintenance phase, 77.9% of the olanzapine-treated and 75.3% of the divalproex-treated patients left the study. High discontinuation rates in long-term studies of bipolar disorder are not unusual and underscore the difficulty of maintaining patients with bipolar disorder, at least those who have just been discharged on a monotherapy regimen after hospitalization for a manic episode. Bowden et al. (12) reported a dropout rate of 62% of patients treated with divalproex and 76% of patients treated with lithium for 52 weeks. While these are lower than the rates in the current study, it should be noted that the patients in the Bowden et al. study were required to meet criteria for stable recovery before being randomly assigned to maintenance treatments. In that study (12), approximately 35% of the patients in the open-label stabilization phase did not meet those criteria, often because of inadequately controlled manic symptoms. In our study, patients who achieved remission at the end of the acute phase were more likely to complete the present study than were patients who did not achieve remission.

A fourth limitation of the study was that the patients were generally severely ill; the mean baseline total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale was 27.7, most patients had a large number of prior episodes (93.6% had more than three previous manic, depressed, or mixed episodes at study entry), and a large proportion (57.4%) had a rapid cycling course. Therefore, our results may not generalize to less severely ill patients encountered in nonacademic clinical settings.

During this 47-week, randomized, double-blind trial for acute mania in which flexibly dosed olanzapine and divalproex were compared, olanzapine produced a faster improvement than divalproex in symptoms of mania as rated by the Young Mania Rating Scale. Compared to the previously reported first 3 weeks of treatment, longer treatment was associated with further improvement in both groups. Of the a priori clinically meaningful categorizations defining remission and response, olanzapine was superior for syndromal remission of mania. For both olanzapine and divalproex, symptomatic remission appeared earlier than syndromic remission. However, remission by both symptomatic and syndromic definitions was significantly more rapid for the olanzapine-treated patients, but the differences in remission rates between groups later in the trial were nonsignificant. There were similar rates of discontinuation due to adverse events with the two treatments, although the pattern of the most common adverse events differed between the groups. Olanzapine was associated with more weight increase early in treatment, but weight increases did not differ significantly between groups in patients who remained in treatment longer. Although the primary efficacy outcome of this trial favored olanzapine, both olanzapine and divalproex demonstrated efficacy for bipolar mania. In selecting pharmacological treatment, the clinician should consider both safety and efficacy as well as patient-specific considerations.

Acknowledgments

The following institutions and individuals participated in this clinical trial: Jay Amsterdam, M.D., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; George Bartzokis, M.D., Little Rock VA Medical Center, North Little Rock, Ark.; Louise Dabiri-Beckett, M.D., IPS Research Company, Oklahoma City; Gary Booker, M.D., IPS Research Company, Shreveport, La.; Ron Brenner, M.D., St. John’s Episcopal Hospital, Far Rockaway, N.Y.; David Brown, M.D., Community Clinical Research, Inc., Austin, Tex.; Timothy Byrd, M.D., Charter Springs Behavioral Clinic, Ocala, Fla.; Franca Centorrino, M.D., McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; James Chou, M.D., Bellevue Hospital, New York; Anthony Claxton, M.D., and Hermant Patel, M.D., University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City; Lori Davis, M.D., VA Medical Center, Tuscaloosa, Ala.; Jose E. De La Gandara, M.D., North Broward Neurological Institute Memory Disorder Center, Pompano Beach, Fla.; G. Michael Dempsey, M.D., Memorial Hospital, Albuquerque, N.Mex.; Rif El-Mallakh, M.D., University of Louisville School of Medicine; Louis Fabre, M.D., Fabre Research Clinics, Houston; David Feifel, M.D., University of California at San Diego Medical Center; Brent Forester, M.D., Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester, Manchester, N.H.; Arthur Freeman III, M.D., Louisiana State University Medical Center, Shreveport, La.; Alan Green, M.D., Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Boston; Sanjay Gupta, M.D., Psychiatric Network, P.C., Olean, N.Y.; Robert Horne, M.D., Lake Meade Hospital, Las Vegas; Fuad Issa, M.D., Clinical Research Center of Northern Virginia, Falls Church, Va.; Robert Jamieson, M.D., Psychiatric Consultants, P.C., Nashville, Tenn.; Christopher Kelsey, M.D., San Diego Center for Research; Louis Ari Kopolow, M.D., Associated Psychotherapy Centers, Gaithersburg, Md.; Jeff Mitchell, M.D., Laureate Psychiatric Clinic and Hospital, Tulsa, Okla.; Cesar Munoz, M.D., University of Alabama at Birmingham; Fred Petty, M.D., Ph.D., VA Medical Center, Dallas; Michael Plopper, M.D., Mesa Vista Hospital, San Diego; Joanchim Raese, M.D., Knollwood Psychiatric and Chemical Dependency Center of Charter Hospital, Murietta, Calif.; Jeffery Rausch, M.D., Medical College of Georgia, Augusta; Robert Riesenberg, M.D., Atlanta Center for Medical Research, Decatur, Ga.; Leon Rubenfaer, M.D., Harbor Oaks Hospital, Farmington Hills, Mich.; John Schmitz, M.D., Midwest Psychiatric Consultants, P.C., Kansas City, Mo.; Taylor Segraves, M.D., Ph.D., MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland; Philip Seibel, M.D., Contemporary Behavioral Research, L.L.C., Washington, D.C.; G. Michael Shehi, M.D., Mountain View Hospital, Gadsden, Ala.; Marshall Thomas, M.D., University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver; Kathleen Toups, M.D., Bay Area Research Institute, Lafayette, Calif.; Dan Wilson, M.D., Pauline Warfield Lewis Center, Cincinnati; Tai P. Yoo, M.D., Mercy Hospital, Detroit.

|

|

|

Received May 28, 2002; revision received Nov. 26, 2002; accepted Dec. 23, 2002. From the Lilly Research Laboratories; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.; the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, NIMH, Bethesda, Md.; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas; the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital, Los Angeles; and the Department of Psychiatry, Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago. Address reprint requests to Dr. Tohen, Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN 46285; [email protected] (e-mail). Sponsored by Lilly Research Laboratories.

Figure 1. Change From Baseline in Mean Total Score on Young Mania Rating Scale for Bipolar Patients in 47-Week Study of Olanzapine and Divalproex Treatment for Acute Maniaa

aAt week 47 the numbers of subjects were 19 for olanzapine and 21 for divalproex.

bSignificant difference between groups (p<0.05, mixed model repeated-measures analysis of variance).

cSignificant difference between groups (p<0.01, mixed model repeated-measures analysis of variance).

1. Tohen M, Angst J: Epidemiology of bipolar disorder, in Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Edited by Tsuang MT, Tohen M. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2002, pp 427-444Google Scholar

2. Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT: Outcome in mania: a 4-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1106-1111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Montgomery S, van Zwieten-Boot B, Angst J, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Chengappa R, Goodwin G, Lecrubier Y, Licht R, Nolen WA, Sachs G, Saint Raymond A, Storosum J, Suppes P, van Ree JM: ECNP Consensus Meeting March 2000 Nice: guidelines for investigating efficacy in bipolar disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001; 11:79-88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Suppes T, Gebre-Medhin P, Cohen BM: Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:220-228Link, Google Scholar

5. Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, Kmetz GF, Upadhyaya VH, Tugrul KC, Bourne ML: Twelve-month outcome after a first hospitalization for affective psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:49-55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Zis AP, Goodwin FK: Major affective disorder as a recurrent disease: a critical review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:835-839Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Rice J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RM: Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. JAMA 1986; 255:3138-3142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, David JM, Rush AJ, Small JG, Garza-Trevino ES, Risch C, Goodnick PJ, Morris DD: Efficacy of divalproex versus lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918-924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Pope HG Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI: Valproate in the treatment of acute mania: a placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:62-68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V, Olanzapine HGEH Study Group: Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702-709Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, Banov MC, McElroy SL, Janicak PG, Zhang F, Toma V, Francis BJ, Sanger TM, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:841-849Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, Pope HG Jr, Chou JCY, Keck PE Jr, Rhodes LJ, Swann AC, Hirschfeld RMA, Wozniak PJ (Divalproex Maintenance Study Group): A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:481-489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gelenberg AJ, Kane JM, Keller MB, Lavori P, Rosenbaum JF, Cole K, Lavelle J: Comparison of standard and low serum levels of lithium for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1489-1493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Greil W, Ludwig-Mayerhofer W, Erazo N, Schochlin C, Schmidt S, Engel RR, Czernik A, Giedke H, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Osterheider M, Rudolf GAE, Sauer H, Tegeler J, Wetterling T: Lithium versus carbamazepine in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders—a randomized study. J Affect Disord 1997; 43:151-161Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, Kraemer H, Rush AJ: Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1164-1169Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, Zarate CA, Suppes T, Ketter TA, Milton DR, Risser R, Gilmore JA, Breier A, Tollefson GA: Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1011-1017Link, Google Scholar

17. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Version (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

19. Physicians’ Desk Reference, 55th ed. Oradell, NJ, Medical Economics Company, 2001Google Scholar

20. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Spearing M, Post R, Leverich G, Brandt D, Nolen W: Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI for bipolar disorder: the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res 1997; 73:159-171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261-276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Tohen M, Stoll AL, Strakowski SM, Faedda GL, Mayer PV, Goodwin DC, Kolbrener ML, Madigan AM: The McLean First-Episode Psychosis Project: six-month recovery and recurrence outcome. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:273-282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851-855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Barnes TRE: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672-676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 534-537Google Scholar

28. COSTART: Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms, 5th ed. Rockville, Md, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 1995Google Scholar

29. Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, Swann AC, Wozniak P, Somerville KW: A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:1148-1155Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kinon BJ, Basson B, Gilmore JA, Tollefson GD: Long-term olanzapine treatment: weight change and weight-related health factors in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:92-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Biton V, Mirza W, Montouris G, Vuong A, Hammer AE, Barrett PS: Weight change associated with valproate and lamotrigine monotherapy in patients with epilepsy. Neurology 2001; 56:172-177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson G, Tran P: Safety of olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 10):13-17Google Scholar

33. Czekalla J, Beasley CJ, Dellva M, Berg PH, Grundy S: Analysis of the QTc interval during olanzapine treatment of patients with schizophrenia and related psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:191-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Czekalla J, Kollack-Walker S, Beasley CM Jr: Cardiac safety parameters of olanzapine: comparison with other atypical and typical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 2):35-40Google Scholar