Suicide Risk in Placebo-Controlled Studies of Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to determine if fear of an increased risk of attempted suicide in placebo groups participating in placebo-controlled studies is an argument against the performance of placebo-controlled trials in studies of major depression. METHOD: All short-term and long-term, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies that were part of a registration dossier for the indication of major depression that were submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board, the regulatory authority of the Netherlands, from 1983 to 1997 were reviewed for attempted suicide. In addition, all long-term, placebo-controlled studies from a MEDLINE search that were conducted in the last decade in patients with major depression were assessed for attempted suicide. RESULTS: In 77 short-term studies with 12,246 patients in dossiers from the Medicines Evaluation Board, the incidence of suicide was 0.1% in both placebo groups and active compound groups. The incidence of attempted suicide was 0.4% in both placebo groups and active compound groups. In eight long-term studies with 1,949 patients, the incidence of suicide in the placebo groups was 0.0% and 0.2% in the active compound groups. Attempted suicide occurred in 0.7% of both placebo groups and active compound groups. In seven long-term MEDLINE studies, the incidence of attempted suicide in the placebo groups was not higher than in the groups treated with active compound. CONCLUSIONS: Fear of increased risk of attempted suicide in the placebo groups should not be an argument against performing short-term and long-term, placebo-controlled trials in major depression.

In order to prove the efficacy of a drug in treating major depression, short-term, placebo-controlled studies must be conducted (1). Furthermore, maintenance of an effect has to be demonstrated in placebo-controlled, long-term studies before a marketing authorization is granted in Europe. The life-time risk of suicide in patients with depression is 15% (2). Therefore, in placebo-controlled studies, patients treated with placebo might carry an increased risk of committing suicide. Besides all other controversial issues concerning the use of placebo (3, 4), this might be an additional ethical argument against the use of placebo in studies of major depression.

Recently, Khan et al. (5) reported that in short-term studies, the incidence of suicide and attempted suicide did not differ among the placebo- and drug-treated groups in the Food and Drug Administration database. However, this database was quite heterogeneous, including, e.g., pharmacokinetic studies, studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder, studies of panic disorder, and open-label studies, and did not include long-term studies. The objective of our study was to investigate whether we could confirm the results of Khan et al. (5) in a homogeneous database and whether their findings also hold for long-term studies.

Method

All reported and unreported short-term and long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (dose-finding, two-armed, and three-armed studies) that were part of a registration dossier for the indication of major depression and were submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board of the Netherlands were reviewed for completed suicides and suicide attempts. These studies covered the period from the licensing of the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (1983) and included the most recent submission (1997).

Moreover, we conducted a search on MEDLINE with the key words “depression,” “recurrence,” “relapse,” “prevention,” and “study” to obtain additional long-term studies. This search covered 1990 to July 1999. Only placebo-controlled studies in patients suffering from major depression were included. Studies of elderly patients and of patients with chronic depression were excluded to allow generalization of the results to the adult population of patients with major depression. Moreover, studies that were published separately as aggregates of a larger study and studies in languages other than English were excluded.

The Medicines Evaluation Board of the Netherlands is the regulatory authority of the Netherlands. To obtain a marketing authorization, a company must submit a dossier to the Medicines Evaluation Board, which includes information on all clinical trials conducted for a drug under development. These dossiers contain studies that will be published later as well as studies that will never be published. On the basis of the assessment report on a dossier, the Medicines Evaluation Board makes a decision regarding the application for marketing authorization and, in the case of a positive opinion, finalizes the product information text. Short-term studies were defined as studies lasting a maximum of 8 weeks. Long-term studies were defined as lasting longer than 8 weeks.

The material from the Medicines Evaluation Board dossiers was selected from the clinical experts’ report on these dossiers and the summary tables of the studies. If necessary, individual studies were assessed. All suicides and suicide attempts that were mentioned in these studies and that occurred during or shortly after the placebo-controlled phase of these studies (as defined in the individual study protocols) were considered for our study. The a priori definitions of “completed suicide” and “suicide attempt” in our investigation were those used in the studies submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board. As the dossiers submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board are confidential and are the property of pharmaceutical companies, the dossiers were made anonymous by selective numbering. The long-term studies from MEDLINE were assessed for completed suicides and attempted suicides.

Analyses were based on the intention-to-treat population. The intention-to-treat analysis included all patients who were randomly assigned to study groups. We computed 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the differences between placebo and active compounds, with respect to percentage of completed suicides and percentage of suicide attempts.

Results

A total of 10 dossiers were submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board for application of the indication “major depression.” In our study, only nine dossiers could be used, because in one dossier no data on attempted suicide were available.

Short-Term Studies

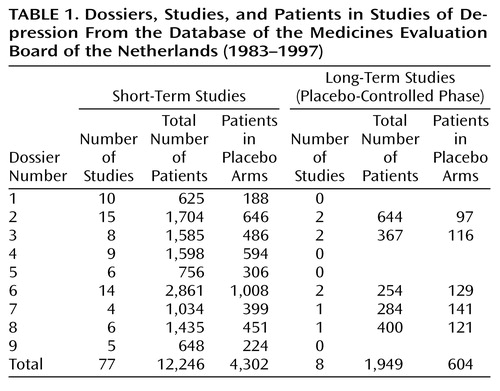

The nine dossiers examined concerned 77 short-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies conducted with 12,246 patients (Table 1). The duration of treatment was 4 weeks in 10 studies, 5 weeks in four studies, 6 weeks in 54 studies, and 8 weeks in five studies. In four studies the exact duration could not be established. The mean length of the studies was 5.8 weeks, and the median length was 6 weeks. Fifty short-term studies were conducted in outpatients, 10 in inpatients, and seven in in- and outpatients; 10 studies did not provide this information. “Suicidal patients” were excluded in 64 studies. In three studies, being “suicidal” was not an exclusion criterion, and in 10 studies this criterion could not be determined.

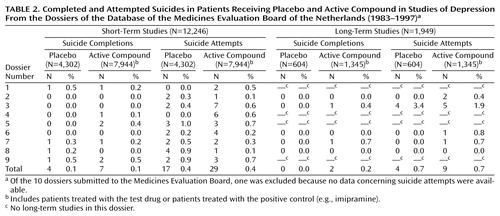

Four of 4,302 patients committed suicide in the summed placebo groups (0.1%), while in the active compound groups, seven of 7,944 patients (0.1%) committed suicide (Table 2). In the placebo groups, suicide was attempted by 17 of 4,302 patients (0.4%) and in the active compound groups by 29 of 7,944 patients (0.4%). There was no difference between the groups.

Long-Term Studies

Eight long-term studies concerning 1,949 patients were submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board; seven were randomized withdrawal studies for sustained responders, and one was an extension study for responders without randomization. The duration of the placebo-controlled phase of these studies varied from 24 to 52 weeks. The mean length of the studies was 38.3 weeks, and the median length was 36 weeks. All of the long-term studies were conducted in outpatients; suicidal patients were excluded in only one placebo-controlled withdrawal study.

None of 604 patients committed suicide in the placebo groups (0.0%), while two of 1,345 patients (0.2%) committed suicide in the active compound groups (Table 2). Suicide was attempted by four of 604 patients (0.7%) in the placebo groups and by nine of 1,345 patients treated with an active compound (0.7%). Again, there was no difference between the groups.

MEDLINE Long-Term Studies

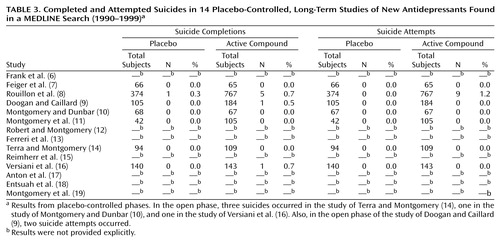

The MEDLINE search resulted in a group of 14 studies (Table 3); 11 were randomized withdrawal studies in sustained responders (6–16), and three were extension studies in responders without randomization (17–19). The duration of the placebo-controlled portion of the withdrawal phase varied from 24 weeks to 3 years (mean=52 weeks, median=46 weeks), and for the extension studies without randomization, the duration was 1–2 years. In the Method section of all withdrawal studies, the exclusion of suicidal patients was not mentioned explicitly. In the extension studies, suicidal patients were excluded from the group of responders in the short-term phase.

In seven withdrawal studies, rates of attempted suicide were provided. In the study of Rouillon et al. (8), more suicide attempts were observed in the active compound group than in the placebo group—a statistically significant finding. In all other studies, no difference between active treatment groups and placebo groups was found for suicide attempts.

Discussion

Our results show that in both short-term and long-term placebo-controlled trials, the rates of suicide and attempted suicide did not differ between placebo-treated patients and patients treated with an active compound. These results should be interpreted with caution, because in one dossier, no data were available for suicide and attempted suicide and four other studies did not describe the duration of treatment. In almost all of the studies, the patients included had to fulfill DSM criteria for major depression: DSM-III criteria for the patients in the early studies, DSM-III-R criteria for the patients in the later studies, and DSM-IV criteria for the patients in the recent studies. Because these criteria did not change substantially over time, the patients included in the different studies might be considered a rather homogeneous population.

Short-Term Studies

The studies included in our investigation were part of the registration files of the Medicines Evaluation Board of the Netherlands. Because some drugs are not submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board (e.g., because a company decides to stop further development of the drug), our investigation did not cover all studies conducted in the period 1983–1997. However, as with the “negative” studies in the files, these studies remain mostly unpublished. Therefore, the studies included in our database were probably not much affected by publication bias and were sufficiently informative for the purposes of our investigation.

In most studies, “suicide risk” was considered an exclusion criterion at entry into the particular study. “Suicide risk” was determined by a clinician at entry. Different protocols used different words for “ suicide risk.” Terms such as “serious suicidal risk,” “significant suicidal risk,” “ active suicidal tendencies,” and “known suicidal gestures” were deemed to be exclusion criteria for “suicide risk.” Whether “serious suicidal risk” and “significant suicidal risk” represented passive or active ideation could not be determined from the data submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board. Although “suicide risk” might not be well defined, the relatively low incidence of suicide and attempted suicide in both the analysis by Khan et al. (5) and in ours might indicate that patients with “suicide risk” were indeed excluded from the short-term studies.

Therefore, the results of our investigation are not informative with regard to the effects of medication and placebo on patients at highest risk. Moreover, the study designs allowing patients with serious deterioration to withdraw from the studies and start standard therapy under open conditions may have influenced the rates of suicides and suicide attempts in both placebo groups and active compound groups. However, the objective of our investigation was not to determine if active treatment might protect against suicide attempts.

The suicide rates of our investigation seem to be marginally lower than those of Khan at al. (5). This might be due to the more heterogeneous database used by Khan et al., including, among others, open studies in which “suicide risk” was probably not an exclusion criterion at entry into the study. In conclusion, when patients with “suicide risk” are excluded at entry into a study, the fear of increased risk of attempted suicide in the placebo group is not an argument against the performance of short-term, placebo-controlled studies.

Long-Term Studies

Because long-term studies are often conducted after marketing of a drug, the Medicines Evaluation Board files did not contain all studies conducted in the period 1983–1997. Therefore, the results from the studies obtained from MEDLINE are an important addition to the results of the long-term studies obtained from the Medicines Evaluation Board files. There was only a partial overlapping between the MEDLINE studies and the studies submitted to the Medicines Evaluation Board, indicating that the MEDLINE studies were probably not free from publication bias. Moreover, in only seven studies were attempted suicides rates provided explicitly. In all but one long-term, randomized, placebo-controlled withdrawal study was “suicide risk” not an exclusion criterion. In these studies, an open-label treatment period was followed by a randomized, placebo-controlled withdrawal study of responders. During the withdrawal phase, dropout due to suicidality was determined by the treating clinician.

The results of these long-term studies, in contrast to the results of the short-term studies, can be generalized to the general population of patients with major depression. It has been suggested that long-term use of antidepressants may diminish suicidal risk (20, 21). We did not find a decreased risk of suicide or attempted suicide in the patients treated with an active compound compared to patients treated with placebo in the long-term studies. However, as only a limited number of patients were included in the studies reviewed and the treatment duration of the studies was relatively short, our analysis cannot give a conclusive answer to the question of protection against suicide. Moreover, the objective of our investigation was not to give answers to this question. The results of our study, however, show that fear of increased risk of attempted suicide in the placebo groups cannot be not an argument against the performance of long-term, placebo-controlled withdrawal studies.

|

|

|

Received Aug. 23, 2000; revision received Dec. 29, 2000; accepted Feb. 2, 2001. From the Medicines Evaluation Board of the Netherlands; the Psychiatric Department of the Academic Medical Center; and the Department of Pharmaco-Epidemiology and Pharmacotherapy, University of Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Address reprint requests to Dr. Storosum, Medicines Evaluation Board of the Netherlands, Kalvermarkt 53, P.O. Box 16229, 2500 BE Den Haag, the Netherlands; [email protected] (e-mail); or to Dr. Storosum, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Tafelbergweg 25, 1105 BC Amsterdam, the Netherlands; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. European Commission Directorate-General: Clinical Guidelines: Medicinal Products for Treatment of Depression: The Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the European Union, vol III, Industry, part 2: Eudra/G/96/010. Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities European Commission, 1996Google Scholar

2. Guze SB, Robins E: Suicide and primary affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1970; 117:437-438Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rothman KJ, Michels KB: The continuing unethical use of placebo controls. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:394-398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rothman KJ, Michels KB, Baum M: Declaration of Helsinki should be strengthened. Br Med J 2000; 321:442-445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Khan A, Warner HA, Brown WA: Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:311-317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush J, Weissman MM: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851-855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Feiger AD, Bielski RJ, Bremner J, Heiser JF, Trivedi M, Wilcox CS, Roberts DL, Kensler TT, McQuade RD, Kaplita SB, Archibald DG: Double-blind, placebo-substitution study of nefazodone in the prevention of relapse during continuation treatment of outpatients with major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 14:19-28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rouillon F, Serrurier D, Miller HD, Gerard M-J: Prophylactic efficacy of maprotiline on unipolar depression relapse. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:423-431Medline, Google Scholar

9. Doogan DP, Caillard V: Sertraline in the prevention of depression. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:217-222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Montgomery SA, Dunbar G: Paroxetine is better than placebo in relapse prevention and the prophylaxis of recurrent depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 8:189-195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Montgomery SA, Rasmussen JGC, Tanghoj A:24-week study of 20 mg citalopram, 40 mg citalopram, and placebo in the prevention of relapse of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 8:181-188Google Scholar

12. Robert P, Montgomery SA: Citalopram in doses of 20-60 mg is effective in depression relapse prevention: a placebo-controlled 6 month study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 10(suppl 1):29-35Google Scholar

13. Ferreri M, Colonna L, Leger J-M: Efficacy of amineptine in the prevention of relapse in unipolar depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12(suppl 3):39-45Google Scholar

14. Terra JL, Montgomery SA: Fluvoxamine prevents recurrence of depression: results of a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 13:55-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Reimherr FW, Amsterdam JD, Quitkin FM, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Zalecka J, Beasley CM Jr, Michelson D, Roback P, Sundell K: Optimal length of continuation therapy in depression: a prospective assessment during long-term fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1247-1253Google Scholar

16. Versiani M, Mehilane L, Gaszner P, Arnaud-Castiglioni R: Reboxetine, a unique selective NRI, prevents relapse and recurrence in long-term treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:400-406Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Anton SF, Robinson DS, Roberts DL, Kensler TT, English PA, Archibald DG: Long-term treatment of depression with nefazodone. Psychopharmacol Bull 1994; 30:165-169Medline, Google Scholar

18. Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL, Hacket D, Miska S: Efficacy of venlafaxine and placebo during long-term treatment of depression: a pooled analysis of relapse rates. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 11:137-145Medline, Google Scholar

19. Montgomery SA, Reimitz PE, Zivkov M: Mirtazapine versus amitriptyline in the long-term treatment of depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 13:63-73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL: Epidemiological data suggest antidepressants reduce suicide risk among depressives. J Affect Disord 1996; 41:1-8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Isacsson G, Holmgren P, Druid H, Bergman U: The utilization of antidepressants—a key issue in the prevention of suicide: an analysis of 5,281 suicides in Sweden during the period 1992-1994. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 96:94-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar