Low Medial and Lateral Right Pulvinar Volumes in Schizophrenia: A Postmortem Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In this study, the volume and neuronal number of the pulvinar thalamic nucleus in schizophrenia patients were measured. METHOD: The authors examined medial and lateral pulvinar nuclei bilaterally in 27 patients with schizophrenia and 28 normal comparison subjects. RESULTS: In the comparison subjects, the medial pulvinar was larger on the right. The right but not left pulvinar nuclei were smaller in the schizophrenia patients than in the comparison subjects. The number of neurons showed similar trends. CONCLUSIONS: These findings confirm low pulvinar volume in schizophrenia and show that it affects both medial and lateral nuclei. The lateralized findings may reflect pulvinar connections with asymmetrical neocortical regions and their asymmetrical involvement in schizophrenia.

Lower than normal thalamic volumes in schizophrenia have been shown by MRI (1) and autopsy (2) studies. The pulvinar constitutes one-quarter of the thalamus, is disproportionately large in primates, and has a unique developmental trajectory (3). Three pulvinar nuclei are generally recognized (4, 5): the inferior pulvinar, which is visual and projects to extrastriate cortex; the medial pulvinar, linked mainly to association areas of the temporal and inferior parietal lobes, and the lateral pulvinar, which shares features with both the medial and inferior pulvinar.

We know of two stereological studies of the pulvinar in schizophrenia. Byne et al. (6) measured the right pulvinar and found a lower volume and fewer neurons than in comparison subjects. Danos and colleagues (7) examined the medial pulvinar and found bilaterally low volumes. Small pulvinar size is also indicated by MRI findings (8, 9). We sought to extend the evidence for pulvinar involvement in schizophrenia.

Method

Full details of the subjects and tissue processing have been reported previously (10), as have the methods for thalamic morphometry (11). Briefly, we studied 16 men (mean age=62 years, SD=15) and 11 women (mean age=73, SD=16) with DSM-IV schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 15 male (mean age=67, SD=14) and 13 female (mean age=73, SD=14) normal comparison subjects. Their handedness was unknown. Pairs of formalin-fixed, wax-embedded 25-μm sections were taken at 2.5-mm intervals from a point anterior to the pulvinar and throughout its extent, and they were stained with cresyl violet or Weil’s myelin stain. The final group sizes ranged from 21 to 25 subjects because of missing or damaged thalamic blocks. The investigators were blind to subject details. All brains were free of neurodegenerative pathologies (10).

Under a dissecting microscope, the inferior pulvinar was identified and excluded. The remaining pulvinar was divided into medial pulvinar and lateral pulvinar on the basis of the prominent myelinated fiber bundles within the lateral pulvinar and the resulting columnar appearance of the neurons. Our definition of the medial pulvinar included the oral nucleus. The volumes of the medial and lateral pulvinar were estimated by using the Cavalieri principle and adjusted by a factor (1.308) to correct for shrinkage during processing. Neuronal density was estimated by using the optical dissector method and Olympus CAST-Grid 2.0 software (11) (Olympus, Albertslund, Denmark). Nuclei were examined by using a raster search pattern (1.2×1.2 mm2 for lateral pulvinar, 1.5×1.5 mm2 for medial pulvinar) covering the entire nucleus. The counting frame was 103×133 μm2, with a 12-μm depth; nucleoli coming into focus within this depth were counted according to stereological rules. The number of neurons was estimated by multiplying the volume by the neuronal density. The observed coefficient of error (12) ranged from 0.052 to 0.185.

Results

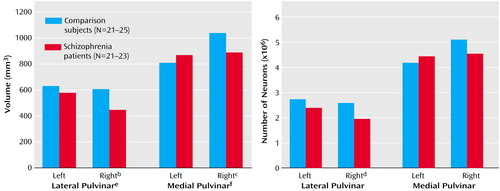

The mean volume of the left lateral pulvinar was 630 mm3 (SD=188) in the comparison subjects and 578 mm3 (SD=175) in the patients with schizophrenia; the mean volume of the right lateral pulvinar was 607 mm3 (SD=208) in the comparison subjects and 447 mm3 (SD=122) in the patients with schizophrenia (Figure 1). Schizophrenia affected lateral pulvinar volume, as the patients had a 26% lower volume on the right but no significant difference on the left. The mean volume of the left medial pulvinar was 809 mm3 (SD=240) in the comparison subjects and 868 mm3 (SD=246) in the patients with schizophrenia; the mean volume of the right medial pulvinar was 1038 mm3 (SD=231) in the comparison subjects and 888 mm3 (SD=222) in the patients with schizophrenia. For the comparison subjects, the volume of the medial pulvinar was significantly greater on the right side than on the left (paired t test: t=6.60, df=16, p<0.001). There was a diagnosis-by-side interaction, with a 14% smaller right medial pulvinar in the schizophrenia patients.

The left lateral pulvinar contained an estimated mean 2.74×106 (SD=0.97) neurons in the comparison subjects and 2.40×106 (SD=0.88) neurons in the patients with schizophrenia; the mean estimates for the right lateral pulvinar were 2.59×106 (SD=1.14) in the comparison subjects and 1.96×106 (SD=0.60) in the patients with schizophrenia (Figure 1). In the left medial pulvinar there were a mean of 4.19×106 (SD=1.29) neurons in the comparison subjects and 4.45×106 (SD=1.16) in the patients with schizophrenia; in the right medial pulvinar the mean estimates were 5.11×106 (SD=1.16) and 4.55×106 (SD=1.66), respectively, giving a nearly significant diagnosis-by-side interaction for medial pulvinar neuronal number (F=3.86, df=1, 30, p=0.06).

The combined mean volume for the medial plus lateral pulvinar in the comparison subjects was 1431 (SD=74) on the left and 1628 (SD=82) on the right; in the patients with schizophrenia the mean values were 1443 (SD=73) and 1311 (SD=57), respectively. This gave a significant diagnosis-by-side effect (F=8.95, df=1, 26, p=0.006), with a significantly lower volume on the right (F=12.02, df=1, 34, p=0.002) but not the left (F=0.32, df=1, 38, p=0.57) in schizophrenia. There was a diagnosis-by-side-by-nucleus interaction (F=5.14, df=1, 26, p=0.04), confirming the differential effect of schizophrenia on the medial and lateral pulvinar. The combined neuronal number for medial plus lateral pulvinar (data not shown) also showed a diagnosis-by-side interaction (F=11.13, df=1, 26, p=0.003) and a lower number on the right side in schizophrenia (F=6.53, df=1, 34, p=0.02).

There were no effects or interactions involving sex, and there were no correlations of pulvinar volume or neuronal number with autopsy delay, fixation time, or neuroleptic exposure (data not shown).

Discussion

We confirmed low pulvinar volume in schizophrenia (6, 7) and showed that the lateral and medial pulvinar are both affected. The same result in three studies, totaling 52 patients and 49 comparison subjects, represents an unusually consistent neuropathological finding, and it is convergent with MRI data (8, 9). Demonstration of small thalamic volumes in neuroleptic-naive patients makes medication an unlikely explanation (9, 13, 14). The findings support a role for the thalamus in schizophrenia (3, 15, 16), although the pathogenesis of its structural involvement remains to be elucidated.

We believe that our asymmetry finding is novel. The right medial pulvinar was larger (28% overall) than the left in all 17 of the comparison subjects for whom both medial pulvinars were available (Figure 1); the lateral pulvinar was symmetrical. In an earlier study (17), rightward medial pulvinar asymmetry was found in six of nine brains, although another study (7) indicated overall medial pulvinar symmetry in 11 subjects. The asymmetry we found may relate to the fact that the medial pulvinar, more so than the lateral pulvinar, is connected with asymmetrical areas of the superior temporal and inferior parietal lobes (4, 5). The abnormalities in schizophrenia were limited to the right side and abolished the normal pulvinar asymmetry, furthering the notion that lesser cerebral asymmetry is important in schizophrenia (10, 18, 19) and adding to the lateralized findings in these brains (10, 20). They are also in agreement with findings of an MRI study showing smaller volumes in the right posterior thalamus (9). However, most other lateralized abnormalities in schizophrenia affect the left side of the brain, and we have no explanation for the right-sided involvement of the medial pulvinar.

Received Aug. 16, 2002; revision received Dec. 7, 2002; accepted Dec. 13, 2002. From the University Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital; and Department of Clinical Neurology, Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, U.K. Address reprint requests to Dr. Harrison, Neurosciences Building, University Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital, Oxford OX3 7JX, U.K.; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Wellcome Trust (Drs. Esiri and Harrison) and the Stanley Medical Research Institute (Drs. Crow and Harrison). The authors thank Brendan McDonald for neuropathological evaluations and Carl Pearson for advice.

Figure 1. Volume and Neuronal Number of the Medial and Lateral Pulvinar Thalamic Nuclei in Normal Comparison Subjects and Subjects With Schizophreniaa

aAll analyses were ANOVAs with age as a covariate.

bSignificantly lower in schizophrenia (F=9.80, df=1, 41, p=0.003).

cSignificantly lower in schizophrenia (F=5.11, df=1, 38, p=0.03).

dSignificantly fewer in schizophrenia (F=5.12, df=1, 41, p=0.03).

eSignificant effect of diagnosis (F=8.88, df=1, 33, p=0.005).

fSignificant diagnosis-by-side interaction (F=9.41, df=1, 30, p=0.004).

1. Konick LC, Friedman L: Meta-analysis of thalamic size in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:28-38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Harrison PJ: The neuropathology of schizophrenia: a critical review of the data and their interpretation. Brain 1999; 122:593-624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jones EG: Cortical development and thalamic pathology in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:483-501Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Jones EG: The Thalamus. New York, Plenum, 1985Google Scholar

5. Pearson RCA: Dorsal thalamus, in Gray’s Anatomy, 38th ed. Edited by Williams PL. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1995, pp 1080-1091Google Scholar

6. Byne W, Buchsbaum MS, Mattiace LA, Hazlett EA, Kemether E, Elhakem SL, Purohit DP, Haroutunian V, Jones L: Postmortem assessment of thalamic nuclear volumes in subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:59-65Link, Google Scholar

7. Danos P, Baumann B, Kramer A, Bernstein H-G, Stauch R, Krell D, Falkai P, Bogerts B: Volumes of thalamic association nuclei in schizophrenia: a postmortem study. Schizophr Res 2003; 60:141-155Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Byne W, Buchsbaum MS, Kemether E, Hazlett EA, Shinwari A, Mitropoulou V, Siever LJ: Magnetic resonance imaging of the thalamic mediodorsal nucleus and pulvinar in schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:133-140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Gilbert AR, Rosenberg DR, Harenski K, Spencer S, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS: Thalamic volumes in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:618-624Link, Google Scholar

10. McDonald B, Highley JR, Walker MA, Herron BM, Cooper SJ, Esiri MM, Crow TJ: Anomalous asymmetry of fusiform and parahippocampal gyrus gray matter in schizophrenia: a postmortem study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:40-47Link, Google Scholar

11. Cullen TJ, Walker MA, Parkinson N, Craven R, Crow TJ, Esiri MM, Harrison PJ: A postmortem study of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003; 60:157-166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Gundersen HJG, Jensen EB: The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microscopy 1987; 147:229-263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pakkenberg B. The volume of the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus in treated and untreated schizophrenics. Schizophr Res 1992; 7:95-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gur RE, Maany V, Mozley PD, Swanson C, Bilker W, Gur RC: Subcortical MRI volumes in neuroleptic-naive and treated patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1711-1717Link, Google Scholar

15. Andreasen NC: The role of the thalamus in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:27-33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Lewis DA, Cruz DA, Melchitzky DS, Pierri JN: Lamina-specific deficits in parvalbumin-immunoreactive varicosities in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia: evidence for fewer projections from the thalamus. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1411-1422Link, Google Scholar

17. Eidelberg D, Galaburda AM: Symmetry and asymmetry in the human posterior thalamus. Arch Neurol 1982; 39:325-332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Crow TJ: Temporal lobe asymmetries as the key to the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:433-443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Pearlson GD, Petty RG, Ross CA, Tien AY: Schizophrenia: a disease of heteromodal association cortex? Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:1-17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Highley JR, Walker MA, Esiri MM, Crow TJ, Harrison PJ: Asymmetry of the uncinate fasciculus: a post-mortem study of normal subjects and patients with schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex 2002; 12:1218-1224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar