Correlates of Change in Functional Status of Institutionalized Geriatric Schizophrenic Patients: Focus on Medical Comorbidity

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Impairment in basic self-care skills is common in patients with schizophrenia and is even more severe in elderly patients with a chronic course of institutional care. While cognitive impairment has proven to be a major predictor of overall functional deficit in schizophrenia, other potential factors, such as medical comorbidity, need to be considered. METHOD: Geriatric institutionalized schizophrenic patients (N=124) were assessed three times over 4 years to determine levels of positive and negative symptoms, impairment in activities of daily living, impairment in cognitive functioning, and medical problems. Path analysis was used to determine which variables best predicted changes in self-care functions. RESULTS: Functional status, negative symptoms, cognitive functions, and health status all significantly worsened during the follow-up. The path analyses showed that change in health status did not predict change in activities of daily living after the analysis accounted for negative symptoms and cognitive functions. DISCUSSION: The results highlight the relative importance of cognitive impairments in the functional impairments of older schizophrenic patients with increased medical burden.

Impairment in basic self-care skills such as feeding, dressing, bathing, and toileting is common in patients with schizophrenia (1) and is even more severe in elderly patients with a chronic course of institutional care (2). These functional impairments are observed in patients with a wide range of overall outcomes, including both ambulatory (3, 4) and poor-outcome patients (2, 5). Cognitive impairment has proven to be a major predictor of overall functional deficit in schizophrenia. For example, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that greater cognitive impairment early in the course of schizophrenia predicts subsequent poor outcome (6) and interferes with the acquisition of adaptive skills in training programs (see reference 7 for review).

Although age-related cognitive and functional change has not been observed in ambulatory older patients with schizophrenia (8–11), there is both cross-sectional (3, 5, 12, 13) and longitudinal (2, 6, 14, 15) evidence of cognitive and functional deterioration in older poor-outcome (chronically institutionalized) schizophrenic patients. Moreover, the cognitive decline observed in these poor-outcome patients may predict deterioration in overall functional status (2).

There are other potential factors, however, that may significantly contribute to the profound cognitive and functional impairments observed in older poor-outcome patients with schizophrenia. For example, while it is conceivable that institutionalization may produce these deficits, Johnstone et al. (16) found that duration of institutionalization was not associated with severity of functional impairments. Moreover, invasive somatic treatments experienced by these older patients such as ECT, lobotomy, and insulin coma therapy have also proven to be unassociated with cognitive and functional deficits in chronically ill populations (13, 17). Therefore, other causes need to be sought.

Medical illness, which occurs in increased frequency in elderly persons, is a potential contributory factor to both cognitive and functional impairment (18). Because neurological conditions such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease are associated with cognitive and functional impairments (19–22), patients with these neurological problems have been excluded from studies evaluating the cognition and functional status of elderly schizophrenic patients (2, 13–15). However, medical illnesses other than neurological conditions, such as pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases, metabolic abnormalities, endocrinopathies, malignant and nonmalignant tumors, and orthopedic diagnoses, could potentially contribute to cognitive and functional impairment in elderly schizophrenic patients. For example, a relationship between coronary heart disease and cognitive dysfunction has previously been shown in hospitalized nonpsychiatric patients (23). In addition, untreated hypertension (24, 25) and diabetes (26) have been shown to be associated with cognitive decline in nonpsychiatric subjects.

Psychiatric illness may increase the risk for medical burden in the elderly. In a study of inpatients with Alzheimer’s disease, major depression, or schizophrenia, an average of six medical illnesses coexisted with psychiatric illness (27). In this study, 99% of elderly psychiatric inpatients had at least one physical illness, 94% had at least two, and 85% had at least three concurrent medical problems. Because medical comorbidities would be expected to be common in elderly patients with schizophrenia, they could be a contributory factor to cognitive and functional deficits. Therefore, the present study was designed to evaluate institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients to identify variables that best predicted changes in self-care functions associated with the aging process, with particular attention to the influence of medical comorbidity.

Method

Subjects

Subjects in this study were 124 chronically ill schizophrenic inpatients at a state psychiatric facility. The subjects were age 65 or older, had entered a prospective follow-up study of the effects of aging on cognitive, functional, and symptom status, and were available for a total of three assessments. These subjects were part of a group of 308 chronically ill schizophrenic patients over age 65 who were reported on by Davidson et al. (13). Of the 308 patients, 49 were unavailable for the third reassessment because they had died and 135 were unavailable due to relocation or refusal of testing. T tests comparing the demographic and baseline cognitive and symptom variables demonstrated that the group available for the third assessment had significantly higher baseline Mini-Mental State Examination scores than the group who died (t=3.88, df=258, p<0.001) and the group lost to follow-up (t=2.83, df=258, p=0.005). There were, however, no significant differences between these groups in baseline severity of negative and positive symptoms or in level of education. The mean age of the study patients at baseline was 72.4 years (SD=6.3), and the mean number of years of education was 9.7 (SD=3.0). Fifty-six were male subjects in the study group (45%), and the majority of subjects were Caucasian (N=100, 81%).

All subjects met DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia on the basis of an extensive diagnostic workup, with rigorous exclusion of alternative neurological or medical factors that might have produced their psychiatric or cognitive symptoms. The DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia was generated by an a priori systematic approach in which several senior psychologists (three of the authors: P.H., L.W., and M.P.) and psychiatrists reviewed medical records, interviewed collateral informants, and used information obtained from patient interviews to render a diagnosis. Patients were excluded from the study for any disorder that ruled out a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, including mental retardation, substance dependence, brain damage, and other psychiatric diagnoses. The assessment battery described in the next section was carried out by raters who were blind to the subject’s previous ratings and to whether the assessment was the subject’s first, second, or third.

Assessments

Schizophrenic symptoms were examined with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (28). The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale contains 30 items, with seven items rating positive symptoms, seven items rating negative symptoms, and 16 items rating general symptoms, including mood, anxiety, psychomotor activity, and other nonschizophrenic symptoms. Our group has demonstrated good reliability with this instrument and has reported intraclass correlations ranging from 0.86 to 1.0 (all p<0.001) for the 30 items (13). For the purposes of this study, we examined total scores on the positive and negative symptoms subscales as the dependent variables.

For assessment of adaptive functioning, all patients were rated with the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Late Version, a modification of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (27). The scale contains 20 items designed to assess the severity of cognitive, functional, and psychiatric impairments found in moderately to severely demented patients.

The analysis of functional status utilized the total score obtained from the activities of daily living subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Late Version. The activities of daily living subscale includes items assessing toileting, feeding, dressing, and physical ambulation rated on the basis of the best source of information. The items are scored on a graded scale from 0, little or no impairment, to 4, the most severe impairment. The factor loadings for each activity of daily living item on the self-care/motor factor range between 0.66 and 0.78 (30). Given that the activities of daily living factor scores have been shown to correctly classify patients according to mild, moderate, severe, and profound impairment levels with the Clinical Dementia Rating as the criterion measure (30), the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Late Version has demonstrated its potential to measure clinically meaningful change.

Using the patient, caregiver, and chart as sources of information, our group has demonstrated high interrater reliability with the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Late Version in studies of geriatric schizophrenic patients (31) and has demonstrated good construct validity (30), with all intraclass correlations on individual activities of daily living items above 0.76 (31).

Assessment of cognitive functioning was done with the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological battery (32). We have previously demonstrated the validity of this battery in assessing patients with chronic schizophrenia (33). The three elements of the battery used in this study were word list learning and delayed recall, praxic drawings, and the Modified Boston Naming Test.

In word list learning and delayed recall, a 10-item list of words is presented to the subject on three separate learning trials. After each trial, free recall of the list is required of the subject. After the list has been read three times, there is a delay of 5 minutes, after which the subject is asked to recall the word list. The score for cumulative learning over the three trials was used in the analyses.

In praxic drawings, four images (circle, diamond, overlapping rectangles, and cube) are presented to the subject, who is required to copy them exactly. The drawings are scored according to predetermined criteria. The dependent variable was the total score for all four drawings.

The Modified Boston Naming Test requires subjects presented with 15 line drawings to name the objects depicted. Of the 15 drawings, five depict objects with a high frequency of occurrence in spoken English, five with moderate frequency, and five with low frequency. The dependent variable was the total number of correct namings.

Assessment of medical burden was based on the annual mandated medical assessment performed by an internist as part of each subject’s routine care. At each annual assessment, the treating physician compiled a medical problem list on the basis of the patient’s history, physical examination, and available laboratory data. At the time of the study assessment, the current year’s medical problem list was recorded and totaled. The resulting total number of medical problems served as an index of medical burden at the time of the study assessment. The validity of this type of index of medical burden is supported by previous investigations (34–36).

Analyses

To reduce the number of variables used in the analyses, a neuropsychological summary score was created from total Modified Boston Naming Test score, total praxic drawings score, and total word list learning score for trials 1–3. Word list delay scores were not entered into the summary score because this index was highly correlated with learning scores. Each test was standardized, and the three z scores were averaged. The average baseline performance for the study group as a whole was, therefore, set to zero and the magnitude of change in cognitive performance was then calculated by converting the change in individual neuropsychological scores at each follow-up to z scores on the basis of the individual neuropsychological test scores at baseline.

The effect of time on cognitive performance, functional status, symptom severity, and total number of medical problems exhibited by the study population was determined with repeated measures analysis of variance. In addition, z tests were used to test the significance of the differences over the 4-year follow-up between proportions of subjects afflicted with a medical illness affecting specific organ systems. Finally, path analysis based on LISREL (SSI Inc., Lincolnwood, Ill.) was used to examine the relationship between baseline scores and changes in clinical symptoms, cognitive functions, medical burden, and functional status.

Results

Progression of Symptoms

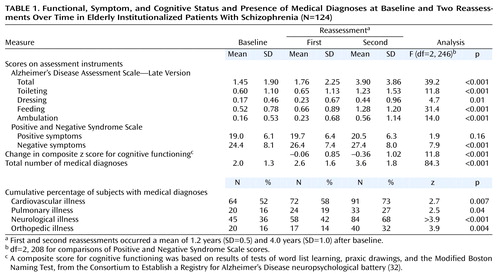

Table 1 summarizes data from the baseline and two follow-up assessments, including average Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Late Version activities of daily living total scores, individual activities of daily living item scores, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale negative and positive subscale scores, change in composite z scores for cognitive functioning, and medical burden index. The first follow-up occurred at a mean of 1.2 years and the second at a mean of 4.0 years after the baseline assessment. Table 1 illustrates the progression of ratings in the domains of activities of daily living functions, psychiatric symptoms, cognitive performance, and medical comorbidity. The mean total score for activities of daily living showed a significant worsening over the 4-year follow-up. Specifically, toileting, dressing, feeding, and ambulation skills all declined over the follow-up. In addition, negative but not positive symptoms significantly worsened over the follow-up. The composite measure of cognitive functioning (naming, praxis, word list learning) declined from baseline performance over the follow-up. Last, the mean number of medical diagnoses carried by the study group increased over the follow-up. Given that an increase in medical burden by only a small subset of the study group could have accounted for the mean change, it is worth noting that 73% of the subjects developed one or more new medical diagnoses over the follow-up. The most common types of new medical illness over the follow-up were cardiovascular, neurological, orthopedic, and pulmonary.

Path Analysis

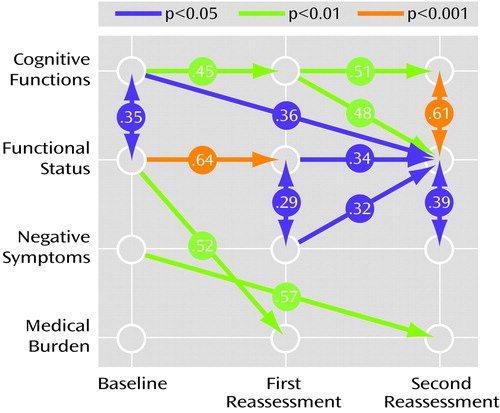

Maximum likelihood model fitting and estimation procedures were used for all of the analyses. The model that was fitted first focused on the relationship between change in cognition and change in functional status. An assumption of these analyses was the constraint of the time-invariant factor loadings of the cognitive functioning indicators (Boston test, praxic drawing, and word list learning test). That is, for each of these longitudinally administered measures, the same factor loading was postulated at all three measurement occasions (baseline, first follow-up, and second follow-up). As extensively discussed in the literature (see reference 37 for example), this factorial invariance restriction was a necessary condition for claiming that the same latent construct had been measured at the three assessments. When fitted to both the covariance matrix and the means of the observed variables, the basic model in Figure 1 was found to be associated with χ2=54.18 (df=42, p=0.19) and a root mean square error of approximation of 0.039 with a 90% confidence interval (CI=0–0.075). All of these goodness-of-fit measures indicated acceptable fit and indicated that this model explained a substantial proportion of the variance.

Evaluation of the predictive role of cognitive difficulties for functional status (Figure 1) showed that initial cognitive ability was significantly related to initial functional status (maximum likelihood estimate [MLE]=–1.54, SE=0.71, t=–2.18, df=123, p<0.05) and that change in cognition from the second to the third assessment was also significant in its effect on change in functional status from the second to the third assessment (MLE=–0.54, SE=0.08, t=–6.98, df=123, <0.001). This result indicated that greater degrees of cognitive decline from the second to the third assessment were associated with concurrent greater loss in functional status from the second to the third assessment. Moreover, the influence of initial cognition (MLE=–0.19, SE=0.09, t=–2.08, df=123, p<0.05) and change in cognition from the first to the second assessment (MLE=–0.37, SE=0.13, t=–2.74, df=123, p<0.01) predicted change in functional status from the second to the third assessment. This result indicated that lower baseline cognitive performance and greater magnitude of cognitive decline from the first to the second assessment were associated with subsequent greater loss in functional status from the second to the third assessment. However, there was no significant relationship of baseline cognitive ability with change in functional status from the first to the second assessment (MLE=0.001, SE=0.06, t=–0.02, df=123, p=0.98). Change in functional status from first to second assessment was significantly related to change in functional status from the second to the third assessment (MLE=–0.28, SE=0.14, t=–2.04, df=123, p<0.05). Finally, initial functional status was significantly related to change in functional status from the first to the second assessment (MLE=–1.40, SE=0.37, t=–3.73, df=123, p<0.001) but not to subsequent change in functional status from the second to the third assessment points (MLE=–0.69, SE=0.49, t=–1.40, df=123, p=0.15).

Conversely, evaluation of the predictive role of functional status on cognitive performance (Figure 1) showed that baseline functional status (MLE=0.37, SE=0.22, t=1.66, df=123, p<0.10) and change in functional status from the first to the second assessment point (MLE=0.35, SE=0.20, t=1.74, df=123, p<0.08) had nonsignificant relationships to change in cognition from the second to the third measurement. In addition, baseline functional status had no significant effect on change in cognitive functioning from the first to the second assessment (MLE=0.24, SE=0.18, t=1.33, df=123, p=0.19). However, initial cognition was significantly related to change in cognition from the first to the second assessment (MLE=–4.83, SE=1.60, t=–3.03, df=123, p<0.005) but not to change in cognition from the second to the third assessment (MLE=–1.54, SE=1.39, t=–1.11, df=123, p=0.24). The change in cognition from the first to the second assessment also had a significant effect on change in cognition from the second to the third measurement (MLE=–0.46, SE=0.17, t=–2.75, df=123, p<0.01).

To examine whether some of the above findings may be explained with relationships between negative or positive symptoms and increased medical problems of the patients, two saturated models were next fitted by including medical diagnoses and first negative symptoms and then positive symptoms in the model described earlier. The results from the first model indicated a significant effect of change in negative symptoms on increase in medical diagnoses (MLE=–0.05, SE=0.02, t=–2.51, df=123, p<0.05) over the entire period. The finding suggested that patients with high levels of negative symptoms had a more salient increase in the number of medical diagnoses across the study period. The effect of change in medical diagnoses on change in functional status over the entire follow-up period was nonsignificant (MLE=0.22, SE=0.23, t=0.93, df=123, p=0.35), and there were no associations between baseline medical problems or change in medical problems and change in functional status at the first reassessment. This finding indicated that, once negative symptoms and cognitive functions are accounted for, an increase in the number of medical diagnoses does not contribute to change in functional status across the study period.

In the otherwise identical model where positive symptoms were substituted for negative symptoms, none of the relationships were significant. That is, there was no significant impact of baseline or change scores for positive symptoms on increase in medical diagnoses or functional status. Similarly, the effect of increase in medical diagnoses on change in functional status was not significant after the analysis accounted for positive symptoms.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a significant decline over a 4-year period in the capacity of poor-outcome elderly schizophrenic patients to carry out activities of daily living. Concomitantly, negative symptoms, cognitive functions, and health status became worse during the follow-up. While all of these changes appeared to be related temporally, change in health status did not predict change in daily living functions after the analysis accounted for negative symptoms and cognitive functions.

The path analysis models suggested that concurrent change in cognitive functioning had the largest effect on change in activities of daily living functions. However, there was also a significant lag effect such that change in cognitive functioning was related to later change in daily living functions. Furthermore, change in health status was not related to change in functional status or cognitive functions either directly or indirectly or with a lag. The ability of cognitive functioning to predict functional status independently of health variables suggests that the association between cognitive functioning and functional status in schizophrenic patients reflects processes different from those underlying the relationship between health and functional capacity found in nonschizophrenic patients (see reference 38, for example).

The lack of association between health variables and cognitive and functional status has been noted previously (21, 39, 40, 41). However, comparisons of our results with the results of earlier studies are difficult because many of these studies assessed nonpsychiatric patients. Indeed, studies that have examined the predictors of functional outcome in schizophrenic patients have demonstrated cognitive ability to be a potent predictor (1, 3, 7). However, only a few have considered the effect of health status (see reference 42). Moreover, the health measure utilized in the study by Auslander et al. (42) (the Quality of Well-Being Scale [43]) was a composite of mobility, physical activity, social activity, and symptom assessments, from which conclusions about the precise relationship between medical comorbidity and functional status cannot be ascertained.

In contrast, other studies have found a significant association between health status and cognitive and functional status in elderly nonpsychiatric patients (25, 26, 38, 44, 45). However, a number of these studies looked at the influence of cognitive and health factors on independent living (38, 44, 45), while the present study examined only self-care skills carried out in an institutional setting. Living independently requires not only independence in self-care skills but also the ability to manage instrumental activities of daily living (advanced living skills), including medication management, cooking, driving, managing financial affairs, etc. The ability to complete activities of daily living in a structured environment may not translate into similar independence at home. It is possible that health status may influence higher functions necessary for independent living and therefore may become significant in a study involving higher-functioning patients living independently (42). Ideally, the inclusion of a nonpsychiatric comparison group in our study would have addressed the question of the uniqueness of this relationship between health status, cognition, and basic self-care skills in schizophrenic patients.

It is a particular challenge to formalize the measurement of medical comorbidity for research purposes given the lack of agreement on how to assess comorbidity. The present study used an index of health status that was based on the total number of comorbid illnesses, whereas other studies contrasting our findings have also used self-report measures and more sensitive measures of illness severity (e.g., blood pressure readings). While the self-report measures may be limited by the observation that older schizophrenic patients may underreport their health problems (39), the more sensitive measures of illness severity may be helpful in future studies. For example, major epidemiological studies have found an inverse relationship between increments in diastolic and systolic blood pressure and cognitive test performance (24, 46, 47). In addition, our model did not control for treatment confounders such as antihypertensive treatment, which has been associated with a decreased risk of cognitive impairment (25).

A major strength of our study is the use of repeated measures over several years, which, in the context of path analysis, suggests a causal relationship. Many previous studies suggesting the involvement of health status in cognitive performance and functional status have not used path analyses (references 25, 26, and 45, for example). Therefore, in previous studies the causal relationship between cognitive functions and health status might be the reverse (e.g., cognitive impairment and altered blood pressure regulation may both be secondary to silent cerebrovascular lesions) (25).

The results of the present study are not intended to downplay the potential contributions of health status to all possible levels of functional status of schizophrenic patients. Rather, in considering a disease in which cognitive deficits are so profound, the results of the present study highlight the relative importance of cognitive impairments in the functional impairments of schizophrenia. As growing numbers of individuals with severe mental disorders reach older age, there are increasing demands on nursing homes and other assisted living settings to accommodate the needs of this group. The role of cognitive impairment in activities of daily living skills suggests that interventions designed to improve cognitive functioning may also benefit community living (38). Improved pharmacological treatments (48) and psychosocial interventions (49) designed to remediate cognitive impairments or teach compensatory strategies for managing these deficits may offer benefit in this area.

|

Received Aug. 29, 2001; revision received Feb. 21, 2002; accepted April 4, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; and Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, Brentwood, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Friedman, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, Box 1230, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-46436 to Dr. Michael Davidson, the Assessment Core (Dr. Harvey, principal investigator) of the Mount Sinai Geriatric Schizophrenia Clinical Research Center grant MH-56083 (Dr. Davis, principal investigator), and the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center.

Figure 1. Significant Relationships of Cognitive, Functional, and Symptom Status and Medical Burden Over Time in Elderly Institutionalized Patients With Schizophrenia (N=124)a

aCognitive functions were measured with tests of word list learning, praxic drawings, and the Modified Boston Naming Test, from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological battery (32). Functional status was measured with the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Late Version, adapted from the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (29). Negative symptoms were measured with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (28). Medical burden reflects the total number of medical problems. First and second reassessments occurred a mean of 1.2 years (SD=0.5) and 4.0 years (SD=1.0) after baseline. Significant standardized regression coefficients resulting from path analysis are presented.

1. Velligan DI, Mahurin RK, Diamond PL, Hazleton BC, Eckert SL, Miller AL: The functional significance of symptomatology and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1997; 25:21-31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Mohs RC, Davidson M, Davis KL: Convergence of cognitive and adaptive decline in late-life schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1999; 35:77-84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM: A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophr Res 1997; 27:181-190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Klapow JC, Evans J, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Koch WL, Jeste DV: Direct assessment of functional status in older patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1022-1024Link, Google Scholar

5. Harvey PD, Leff J, Trieman N, Anderson J, Davidson M: Cognitive impairment and adaptive deficit in geriatric chronic schizophrenic patients: a cross national study in New York and London. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:1001-1007Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D: National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia: prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:239-246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321-330Link, Google Scholar

8. Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris MJ, Jeste DV: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:469-476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Goldberg T, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR: Course of schizophrenia: neuropsychological evidence for static encephalopathy. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:797-804Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Sadek JR, Perry W, Jeste DV: The nature of learning and memory impairments in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995; 1:88-99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV: Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:24-32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Arnold SE, Gur RE, Shapiro RM, Fisher KR, Moberg PJ, Gibney MR, Gur RC, Blackwell P, Trojanowski JQ: Prospective clinicopathologic studies of schizophrenia: accrual and assessment of patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:731-737Link, Google Scholar

13. Davidson M, Harvey PD, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Knobler HY, Losonczy MF, Keefe RSE, Katz S, Frecska E: Severity of symptoms in chronically institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:197-207Link, Google Scholar

14. Friedman JI, Harvey PD, Coleman T, Moriarty PJ, Bowie C, Parrella M, White L, Adler D, Davis KL: Six-year follow-up study of cognitive and functional status across the lifespan in schizophrenia: a comparison with Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1441-1448Link, Google Scholar

15. Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, Parrella M, White L, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL: Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:32-40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Johnstone EC, Owens DGC, Gold A, Crow TJ, Macmillan JF: Institutionalization and the defects of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139:195-203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Harvey PD, Mohs RC, Davidson M: Leukotomy and aging in chronic schizophrenia: a follow-up study 40 years after psychosurgery. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:723-732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Cavanaugh SA, Wettstein RM: The relationship between severity of depression, cognitive dysfunction, and age in medical inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:495-496Link, Google Scholar

19. Logsdon RG, Teri L, Larson EB: Driving and Alzheimer’s disease. J Gen Intern Med 1992; 7:583-588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Skoog I, Berg S, Johansson B, Palmertz B, Andreasson LA: The influence of white matter lesions on neuropsychological functioning in demented and non-demented 85-year-olds. Acta Neurol Scand 1996; 93:142-148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Jelicic M, Kempen GI: Cognitive function in community-dwelling elderly with chronic medical conditions. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:1039-1041Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Miller BL, Lesser IM, Boone KB, Hill E, Mehringer CM, Wong K: Brain lesions and cognitive function in late-life psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158:76-82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Barclay LL, Weiss EM, Mattis S, Bond O, Blass JP: Unrecognized cognitive impairment in cardiac rehabilitation patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988; 36:22-28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Elias MF, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Cobb J, White LR: Untreated blood pressure level is inversely related to cognitive functioning: the Framingham study. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 138:353-364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kilander L, Nyman H, Boberg M, Hansson L, Lithell H: Hypertension is related to cognitive impairment: a 20-year follow-up of 999 men. Hypertension 1997; 31:780-786Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Gregg EW, Yaffe K, Cauley JA, Rolka DB, Blackwell TL, Narayan KM, Cummings SR (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group): Is diabetes associated with cognitive impairment and cognitive decline among older women? Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:174-180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Zubenko GS, Marino LJ Jr, Sweet RA, Rifai AH, Mulsant BH, Pasternak RE: Medical comorbidity in elderly psychiatric inpatients. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:724-736Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Kay SR: Positive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1991Google Scholar

29. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL: A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:1356-1364Link, Google Scholar

30. Kincaid MM, Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Putnam KM, Powchik P, Davidson M, Mohs RC: Validity and utility of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Late Version (ADAS-L) for measurement of cognitive and functional impairment in geriatric chronic schizophrenic inpatients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:76-81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Harvey PD, Davidson M, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Mohs RC: Assessment of dementia in elderly schizophrenics with structured rating scales. Schizophr Res 1992; 7:85-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, Clark C: The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD), part I: clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1989; 39:1159-1165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Davidson M, Harvey P, Welsh KA, Powchik P, Putnam KM, Mohs RC: Cognitive functioning in late-life schizophrenia: a comparison of elderly schizophrenic patients and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1274-1279Link, Google Scholar

34. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stock JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF III: Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 1992; 41:237-248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Lacro JP, Jeste DV: Physical comorbidity and polypharmacy in older psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:146-152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Graves EJ: Detailed diagnoses and procedures: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1993. Vital Health Stat 1995; 122:1-288Google Scholar

37. Meredith W: 2 wrongs may not make a right. Multivariate Behav Res 1995; 30:89-94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Laukkanen P, Leskinen E, Kauppinen M, Sakari-Rantala R, Heikkinen E: Health and functional capacity as predictors of community dwelling among elderly people. J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53:257-265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Jeste DV, Gladsjo JA, Lindamer LA, Lacro JP: Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:413-430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. MacNeill SE, Lichtenberg PA: Home alone: the role of cognition in return to independent living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78:755-758Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Ahto M, Isoaho R, Puolijoki H, Laippala P, Sulkava R, Kivela SL: Cognitive impairment among elderly coronary heart disease patients. Gerontology 1999; 45:87-95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Auslander LA, Lindamer LL, Delapena J, Harless K, Polichar D, Patterson TL, Zisook S, Jeste DV: A comparison of community-dwelling older schizophrenia patients by residential status. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 103:380-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Kaplan RM, Atkins CJ, Timms R: Validity of a quality of well-being scale as an outcome measure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Chronic Dis 1984; 37:85-95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Greene VL, Ondrich JI: Risk factors for nursing home admissions and exits: a discrete-time hazard function approach. J Gerontol 1990; 45:S250-S258Google Scholar

45. Rockwood K, Stolee P, McDowell I: Factors associated with institutionalization of older people in Canada: testing a multifactorial definition of frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:578-582Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Laurner LJ, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Foley D, Havalick RJ: The association between midlife blood pressure and late life cognitive functioning: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA 1995; 274:1846-1851Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Swan GE, Carmelli D, LaRue A: Performance on the digit symbol substitution test and 5-year mortality in the Western Collaborative Group Study. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141:32-40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Harvey PD, Keefe RSE: Studies of cognitive change in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:176-184Link, Google Scholar

49. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Huntzinger C, Ritch J, Ledbetter N, Prihoda TJ, Miller AL: Randomized controlled trial of the use of compensatory strategies to enhance adaptive functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1317-1323Link, Google Scholar