Studies of Cognitive Change in Patients With Schizophrenia Following Novel Antipsychotic Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Novel antipsychotic medications have been reported to have beneficial effects on cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia. However, these effects have been assessed in studies with considerable variation in methodology. A large number of investigator-initiated and industry-sponsored clinical trials are currently underway to determine the effect of various novel antipsychotics on cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia. The ability to discriminate between high- and low-quality studies will be required to understand the true implications of these studies and their relevance to clinical practice. METHOD: This article addresses several aspects of research on cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia, emphasizing how the assessment of cognitive function in clinical trials requires certain standards of study design to lead to interpretable results. RESULTS: Novel antipsychotic medications appear to have preliminary promise for the enhancement of cognitive functioning. However, the methodology for assessing the treatment of cognitive deficits is still being developed. CONCLUSIONS: Researchers and clinicians alike need to approach publications in this area with a watchful eye toward methodological weaknesses that limit the interpretability of findings.

The past 10 years have seen the introduction of several new antipsychotic medications (referred to as “novel” or “atypical” antipsychotics). While one of these medications, clozapine, has been in use for years in Europe, it was not introduced in the United States until 1990. Among the advantages of novel antipsychotics over “traditional” or “conventional” antipsychotics are reduced extrapyramidal side effect profiles (1, 2), reduced risk for tardive dyskinesia (3, 4), greater effects on the negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia (5–7), and possible beneficial effects on cognitive functioning. A total of 24 published reports from 20 different studies that were not completely naturalistic have indicated that clozapine (8–21), risperidone (20–28), ziprasidone (29), aripiprazole (29), olanza-pine (21, 30), and quetiapine (31) have beneficial effects on cognitive functioning compared to treatment with traditional antipsychotics. Furthermore, adjunctive treatments such as adrenergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic agents are under investigation in patients with schizophrenia. These agents have the potential to enhance cognition independently of antipsychotic treatment.

Cognitive enhancement has the potential to lead to several substantial benefits. Cognitive functioning is a correlate of global and specific functional outcome in schizophrenia (32). Cognitive impairments consistently account for significant variance in measures of functional status, such as social and occupational disability (32, 33), and are more strongly related to functional outcome than other aspects of the illness such as positive symptom severity (32, 33). Previously published research has supported the cost-benefit ratio of novel antipsychotic medications in terms of compliance, reduction of relapse, and treatment of positive and negative symptoms (34–41). Since social and occupational disability may generate the largest indirect costs of the illness (42), treatment of cognitive deficits may have an enormous impact on the cost and disability associated with schizophrenia. Thus, the societal benefits of cognitive enhancement in patients with schizophrenia could be substantial (43).

Studies of the pharmacological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease have shown that it is possible to identify validly measured, clinically meaningful cognitive change with variants of standard clinical neuropsychological tests. These studies have evolved to the point where standardized cognitive batteries are routinely employed to assess cognitive change in clinical trials and serve as the Food and Drug Administration’s basis for approval of medications to enhance cognition. These studies are not designed to understand the specific neural mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease nor are they designed to understand the mechanisms of pharmacological enhancement of cognition. Rather, these studies are designed to determine if clinically significant change is associated with treatment with a specific pharmacological agent. Separate studies are designed to determine the cognitive deficit profile and the biological underpinnings of these deficits. As a result, the clinical effects of drugs to treat Alzheimer’s disease are studied in clinical trials, while other aspects of the illness are investigated with parallel research studies.

Studies of cognitive enhancement in patients with schizophrenia are in a much earlier stage of development than research in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The majority of studies of cognitive enhancement in patients with schizophrenia up to 1998 used methods that were not consistent with typical clinical trial methodology. When the results of these previous studies were comprehensively evaluated with meta-analytic statistical techniques (44), the overall beneficial effect of treatment with novel antipsychotic medications was statistically significant. However, as we will subsequently describe, these studies have often used weak methodologies. Nearly all of these results must be viewed as tentative pending replication in studies conducted with higher methodological standards.

In addition to previously published work, several large-scale trials and innumerable smaller studies are currently in progress to evaluate the cognitive enhancing effects of novel antipsychotics. This suggests that the readers of this journal will shortly have available a considerable amount of new information on this issue. The goal of many of these studies is to determine if specific novel drugs have differential benefits compared to other novel drugs and conventional antipsychotics. If consistent results indicate patterns of superior efficacy for certain novel medications, the clinical treatment of patients with schizophrenia is likely to be radically changed. However, pharmaceutical companies principally sponsor these trials with a clear interest in specific outcomes. Thus, clinicians and administrators responsible for determining the medications that patients will receive may wish to learn more about the specific issues involved in interpreting the results of clinical trials of cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia.

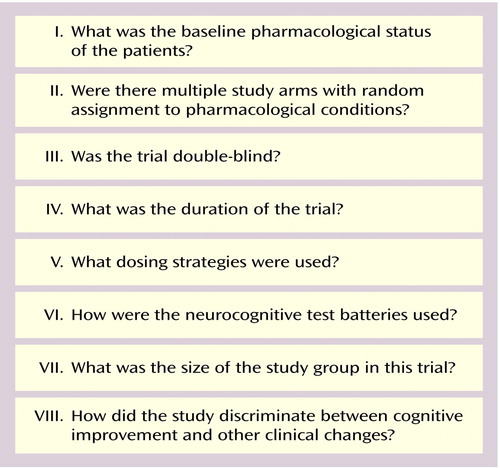

The purpose of this article is to discuss the impact of various methodological and conceptual issues on the results of studies that address cognitive enhancement in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment. These studies have specific methodological needs. The extent to which a study satisfies these considerations may have a pronounced impact on the interpretability of the findings. Figure 1 presents a number of issues to be kept in mind when interpreting the findings of these studies.

In order to evaluate these issues, we reviewed all of the previously published research on cognitive enhancement. A total of 24 previous reports have appeared in refereed journals. Five of these reports (24–28) are from a single clinical trial and will be collapsed as appropriate when considering the numbers of patients and methodologies employed, leading to a total of 20 separate studies that have been completed.

Pharmacological Status at Baseline Assessment

In order to specify changes in cognitive functioning associated with a new treatment, it is important to understand the status of the patients before the transition to the new medication. The ideal pharmacological state of patients at the baseline cognitive assessment is a matter of controversy. Since most schizophrenic patients other than those in their first episode are likely to be receiving some type of pharmacological treatment, there are three important issues to address: 1) the lingering influences of previous antipsychotic treatment, even in patients who have been briefly removed from prior treatment, 2) residual effects of adjunctive treatments used to control side effects, and 3) residual effects of additional treatments used to control agitation or induce sleep.

The length of time that previous treatments have been administered at the time of baseline cognitive assessment is an important factor for understanding the effects of a switch to a new medication. The longer the period of stable treatment, the clearer the understanding of the potential influences of the new treatment. Studies in which patients were all taking similar medications (e.g., haloperidol) for similar periods of time (e.g., 4 or more weeks) before baseline assessment can be most easily interpreted.

Some institutional review boards consider it unethical to remove patients from medication for research purposes. However, there are some circumstances in which unmedicated patients may be available for research. Studies of drug-naive patients are ideal in that they allow examination of the relative beneficial effects on cognition of novel antipsychotic treatment, with no need for concern regarding length of medication-free status. For other patients, medication-free status is often a function of the discontinuation of previous treatment. The duration of discontinuation is important to understand because of the temporal aspects of antidopaminergic effects of typical antipsychotic medications. Oral antipsychotic medications have antidopaminergic effects for at least 2 weeks, while depot medications may have these actions for up to 6 months (45). Thus, a short period of discontinuation of prior medication (e.g., less than 7 days) is not a “true” medication-free assessment.

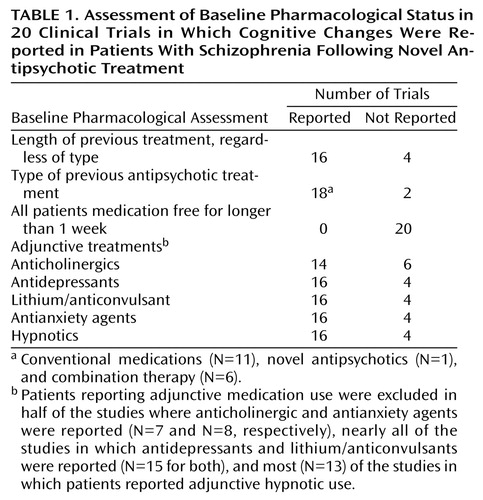

Table 1 presents the baseline pharmacological status of patients in the previous reports of the cognitive effects of novel antipsychotic treatment. The majority of studies reported the length of previous treatment and the type of previous antipsychotic medications received. Not one of the 20 previous clinical trials assessed all patients at baseline while they had been antipsychotic free for periods longer than 7 days. In other studies, some patients were medication free, as a function of having discontinued their medications. Other patients in those studies, however, were receiving medication, leading to considerable variation in baseline antipsychotic status. Thus, in one-third of the studies, it is not possible to determine whether improvements in cognitive functioning associated with a newer antipsychotic were actually an improvement from older treatments, from a medication-free state, or from treatment with some combination of other medications.

In these studies, the adjunctive treatment status at baseline was even less consistent, both in terms of medications allowed and what was reported. More than one-quarter of the reports did not even mention the adjunctive treatment status of the patients at baseline. In addition, while only one study allowed the use of concurrent mood stabilizers or antidepressants, one-half of the studies in which the use of antianxiety agents was reported allowed their use. While these methods are appropriate for effectiveness studies that assess the impact of current psychiatric prescribing practices on treatment-response indices, the most interpretable results of efficacy studies will be yielded by uniformity of treatment at baseline. Until more information is obtained about the effects of novel antipsychotic drugs under conditions of ideal study designs, variation in baseline status will lead to problems in understanding the results of the studies.

Multiple Study Arms With Random Assignment to Pharmacological Conditions

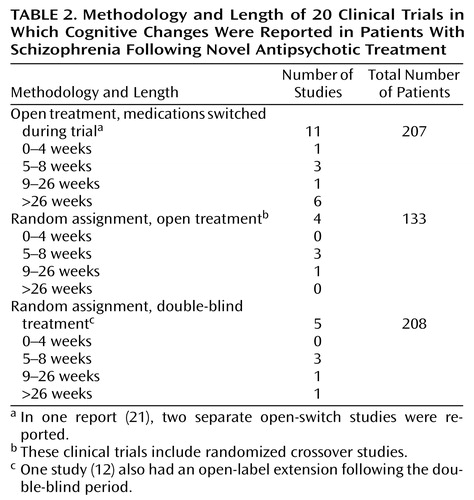

Table 2 presents a summary of the methodologies of the 20 previous clinical trials in which cognitive enhancement was reported following novel antipsychotic treatment. As can be seen, the typical methodology was a “switch” study. This type of study can examine changes associated with the new treatment and has none of the selection biases associated with comparing the cognitive performance of patient groups who have been assigned to a medication group on the basis of clinical judgment (46) or history of treatment response. The clear disadvantage of the single-arm switch study is that there is no way to determine if cognitive changes after the switch are due to the new drug or to other factors (e.g., practice effects, rater or patient expectations, or changes in patient motivation). The best study designs incorporate multiple study arms with distinct treatments to which subjects are randomly assigned. Ideally, this design would include the comparison of one or more novel compounds to treatment with conventional medications. This design has the benefit of separating nonspecific effects, such as practice effects, from the unique treatment effects associated with specific compounds.

Double-Blind Methodology

While open-label studies are common for initial investigations of new treatments, clinical trials presume a double-blind study methodology. As also noted in Table 2, five of the 20 previous clinical trials incorporated a double-blind randomized methodology, with a total of 208 patients studied (which represents the number of patients entered into the study, not the number of patients who completed it).In one of these trials (30), the rate of completion of the study was less than 50% overall and less than 33% in some arms. Thus, the published double-blind database on cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia is relatively small.

The benefits of double-blind studies are clear. In open studies, even if treatment assignment is random, changing the expectations of patients, relatives, raters, and physicians can influence the outcome of treatment either through selective reporting of symptoms by the patient or relatives or through bias on the part of raters. Even though cognitive tests are considered to be objective, there are many mechanisms through which nonblinded cognitive studies can be influenced. For instance, there are several phases of administering, scoring, and interpreting cognitive tests and resultant data before the final data analysis. These phases may be affected by factors such as encouragement or prompting of patients during test performance and consistency in applying scoring rules to performance. Since these factors apply to numerous tests for each subject in a study, the opportunity for subtle biases to create significant spurious findings can increase. Most important, patient motivation to perform on cognitive tests may be influenced by expectations. Patients receiving treatment with a medication in which improvement is clearly expected by the research team may be influenced, overtly or covertly, to increase their effort while being tested. Thus, open-label and double-blind studies have the potential to produce different results, even on tests that have the appearance of objectivity.

Duration of Trial

Many of the previously published studies of cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia have been 6 to 12 weeks in length, while some have been as long as 1 year. Table 2 also presents the duration of the previous studies, as a function of the methodology employed. Only one of the previously published double-blind studies lasted 1 year, while the double-blind phases of the other four studies were relatively short. Open-switch studies typically lasted the longest.

Treatment with the novel antipsychotic medication clozapine has been shown to continue to improve the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia for at least 6 months after initiation of treatment (47–49). If the time course of response of clinical symptoms and cognitive impairment are similar, thorough cognitive enhancement studies should also be of this duration. Since the time course of cognitive enhancement with novel antipsychotics is presently unknown, information about the rate and timing of enhancement is needed from these clinical trials in order to determine if it is possible to identify cognitive “responders versus nonresponders.”

Early Treatment Effects

Statistically significant cognitive changes associated with novel antipsychotic treatment have been demonstrated after treatment periods as brief as 4–8 weeks (24–29). Early evaluation of treatment changes can provide clinically useful information about how soon cognitive performance improvement can be expected and when a medication should be switched because of lack of efficacy in cognitive enhancement.

Later Treatment Effects

Cognitive performance changes later in the course of treatment are at least as important to detect as early treatment effects. Studies that focus only on the narrow window of time following medication initiation will miss long-term effects. Further, it may be unreasonable to expect that cognitive enhancement will have an immediate impact on related aspects of the illness such as adaptive functions, even if cognitive impairment was the sole cause of these deficits. Adaptive functioning deficits are likely to be influenced by a complex array of environmental and individual factors that are unlikely to change in 1 or 2 months. Improvement in functional status may require continued changes in cognitive functioning, or it may result from early cognitive changes reinforced by subsequent alterations in interactions with the environment. The course of cognitive change in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment, much like the course of clinical change, can only be determined with longer-term studies.

Dosing Strategies

Dosing strategies for conventional antipsychotics have varied considerably over time, including even extremely large doses of these medications (e.g., ≥80 mg/day of haloperidol) (50). At the present time, doses that are considerably lower than those used historically are considered most appropriate (51). Higher doses of conventional medications are generally associated with greater extrapyramidal side effects, impaired motor performance, and increased use of anticholinergic medications (52). Furthermore, many cognitive tests require some kind of timed motor response. Motor impairment secondary to extrapyramidal side effects may result in wide-ranging decrements in performance on cognitive tests, and dose reductions may improve performance (53). Older patients appear particularly vulnerable to these adverse effects (54). Thus, the conventional antipsychotic dose, when used as a comparator in a study with novel antipsychotic medications, should be low enough to avoid confusion between cognitive enhancement caused by treatment effects and cognitive improvement caused by release from inappropriate treatment.

Current American dosing standards for healthy, nonelderly patients with schizophrenia are roughly 5–10 mg/day in haloperidol equivalents (250–500 mg in chlorpromazine equivalents). Table 3 presents the conventional medication baseline doses for the previous studies. As can be seen, only 12 of the trials provided information about conventional antipsychotic doses at or immediately before a brief washout preceding the baseline assessment. In the studies where the patients were receiving conventional antipsychotic medications at baseline and the doses were reported, the average dose was close to 1000 mg/day in chlorpromazine equivalents. This suggests that the typical dose a patient received before being transitioned to a newer medication was quite high. When the comparator doses for conventional medications in parallel trials are examined, half of the time the actual dose was not reported, and when it was reported, the average was about 750 mg/day in chlorpromazine equivalents.

These studies, therefore, used comparator doses of conventional antipsychotic medications that were quite high, on average, although the patients randomly assigned to conventional antipsychotic medications in these studies typically experienced a dose reduction compared to the typical baseline dose of a patient entering one of these studies. Thus, in these studies, the reader is unable to separate the effect of the transition to a novel antipsychotic drug from the effect of a dose reduction in general.

Dosages must also be considered in studies comparing novel medications. When risperidone was initially introduced to the market in 1994, the recommended doses were as high as 16 mg/day. The relatively high number of patients who developed extrapyramidal side effects and the evidence of possibly reduced efficacy at higher doses prompted a recommendation that the dose range be reduced to 3–6 mg/day. Adjustments in recommended dosing have also been implemented for olanzapine, where the initial recommendation of 10 mg/day for all patients has been adjusted upward. In a comparison of the cognitive effects of olanzapine and risperidone (30), the dose ranges used were based on older standards, and approximately one-half of the patients treated with risperidone received ≥6 mg/day. For future studies, including those comparing other novel antipsychotics such as ziprasidone and quetiapine, readers will need to attend to the latest information regarding appropriate dosing and ensure that comparisons between medications in studies that they see are based on the most current dosing strategies.

It is uncertain at this point if novel antipsychotic doses can be adjusted to maximize cognitive enhancement, thus producing a “cognitive dose response.” The small study group sizes of the previous reports have not allowed data interpretation that would shed light on specific relationships between newer antipsychotic dose levels and cognitive enhancement. The study group sizes of the previous studies have been too small to identify cognitive responders and nonresponders. Additional research is needed to address this issue.

The concurrent dosing of adjunctive medication poses a more complex interpretive issue for cognitive data. Impairments induced by the adjunctive treatments may influence the extent to which cognitive change can be detected. It is important when considering the potential effects on cognition to know if any cognitive improvements happened in the absence of anticholinergic treatment or despite anticholinergic treatment. Until antipsychotic medications are developed that never require the use of adjunctive medications, the potential adverse cognitive effects of adjunctive medications will still be important to consider.

Neurocognitive Test Batteries

Content

The field of assessment of cognitive functioning in schizophrenia has been a contentious one. As a result, no absolute consensus has developed regarding the specific aspects of cognitive functioning that are the most important in schizophrenia and which tests should be employed to measure them. Rather than make definitive statements about the specific cognitive constructs to be measured and the tests to be used, we will instead describe important issues to be considered when interpreting studies of cognitive enhancement.

Although many different cognitive impairments are found in patients with schizophrenia, only a limited subset of these impairments has been repeatedly determined to be associated with important aspects of functional outcome such as social skill acquisition and employment. These impairments include deficits in learning and secondary memory, attention, and executive functioning (13) as well as, to a lesser extent, motor function and verbal fluency (55). Some of these impairments also predict failure to benefit from treatments designed to enhance functional skills (13). Thus, enhancement of these aspects of cognition have the potential to improve social, functional, and adaptive outcome and may have particular importance for eventual changes in the functional outcome of patients with schizophrenia. For instance, since better verbal memory has been found to be associated with better functional outcome in schizophrenia and spatial-perceptual skills have not, improvement in verbal memory may be a more desired effect in the domain of cognitive enhancement.

Properties

The cognitive tests chosen for use in a clinical trial of novel antipsychotic medication should have several critical properties. All tests require evidence of reliability and validity, but there are other issues that are specifically related to the clinical importance of cognitive enhancement. It is helpful if the tests are standardized so that normal performance can be identified. In contrast to many experimental measures, standardized neuropsychological tests with established norms allow for comparison of patients’ performance to standards for normal subjects. Thus, improvement in performance on the part of a patient with schizophrenia can be compared to what would be expected in a normal individual of similar age and educational status.

Repeated administration of cognitive tests, particularly tests of memory and problem solving, can result in practice effects. The use of alternative forms of the tests avoids improvement caused solely by practice effects. Some tests intrinsically have no alternative forms, such as tests of executive functioning like the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (56), which measure a patient’s ability to learn and apply a single rule or set of rules. Reports of cognitive enhancement in “switch studies” with no parallel comparator group and repeated tasks with the potential for large practice effects can be biased as a result.

Number of Tests and Outcome Measures

It is important to balance the comprehensive coverage of important aspects of cognitive and instrumental functioning against protection from spurious findings caused by violations of statistical conventions. There is an empirical literature on the appropriate ratio of outcome measures to subjects studied, with the typical consensus being that multivariate research requires at least 10 subjects per dependent variable (57, 58). Lower ratios of subjects to measures can lead to systematic measurement bias. Similarly, certain statistical analyses, such as multivariate analysis of variance, cannot be performed with small numbers of subjects relative to the number of tests administered (59). As a result, highly restrictive correction procedures, such as the Bonferroni correction, are typically applied. When these corrections are used, the level of statistical significance required is often extremely small and relatively large effects may not be reported as significant. A related practical issue is the manageability of the assessment. Overly extensive assessments lead to patient attrition. Worse, this attrition is usually selective, with patients at the low end of performance ability more likely to fail to complete the most difficult or lengthy tests. As a result, these types of samples may fail to adequately represent the patients most in need of cognitive enhancement.

Assessment batteries with too few tests run an alternative risk—missing important findings. The absence of certain measures may inaccurately portray the range of improvements available with new medications. Thus, the battery of tests is best if it strikes a balance between coverage that is too broad (i.e., leading to dropout of subjects and reduction of the validity of the statistical procedures) versus too narrow (i.e., leading to a restricted range of findings and restriction of the clinical importance of the assessment).

Presentation of Results

In clinical trials for cognitive enhancement, improvement may be specific to certain cognitive domains. Across multiple measures of cognitive functioning there may be a change profile in which some measures improved to a greater extent, some to a lesser extent, others improved not at all, and, possibly, some worsened. Selective presentation interferes with understanding of the profile of cognitive change. Conversely, the use of a single composite measure, especially in studies with relatively small study group sizes, runs the risk of the results being skewed by large improvements on the part of a few aspects of the battery. As noted earlier, apparent improvements in small-sample studies with multiple tests can often be the result of systematic measurement error.

Size of the Study Group

Study group size is a major concern in clinical trials. Small group sizes may not only fail to demonstrate a positive effect of a medication but can also exaggerate the differential benefits of a target medication by failing to detect improvements associated with the comparator. In addition, studies with small patient group sizes could underestimate the diversity in schizophrenia by sampling from unrepresentative populations (e.g., chronically institutionalized patients). As noted earlier, the standard convention for multivariate behavioral research is at least 10 patients at endpoint per dependent measure.

A statistically significant effect may have essentially no clinical importance. In studies of the clinical effects of conventional antipsychotics, this has proven to be true repeatedly. When effect sizes are calculated for the effects of conventional antipsychotics on clinical symptoms, they are often of a magnitude of two or three standard deviations. In fact, in the pivotal clozapine clinical trial (5), the extent of clinical improvement in the patients randomly assigned to traditional treatment was statistically significant, although clinically trivial. Thus, statistical significance is a relatively minor concern, since any cognitive enhancement effect that has any appreciable clinical significance is very likely to reach statistical significance in a clinical trial. Since patients with schizophrenia routinely perform one or more standard deviations below normative standards on critical cognitive tests (60), an improvement in some aspect of cognitive functioning that has a small effect size according to conventional standards (e.g., an effect size of 0.20) may not have clinical significance. Table 4 presents a weighted average (median) of the improvement effects of novel medications on cognitive functions. This average is weighted for the number of patients in the study and examines either the improvement from baseline in switch studies or the improvement relative to the conventional comparator in parallel studies. As noted previously (44), there was a statistically significant overall effect of newer antipsychotic medications on cognition as of all studies published by July 1998. The level of statistical significance of this effect is likely to be larger now than previously because of a number of newer publications with statistically significant treatment effects.

As can be seen in Table 4, essentially every aspect of cognition improved to a small extent (effect sizes of 0.20 or larger). Some effects were consistently large, with vigilance, verbal fluency, and secondary memory consistently improved to a moderate extent. There are several open questions with regard to these data. First, what is the level of differential effect across newer medications? There have been only two pilot studies that compared newer medications, and these involved very small study group sizes. Second, how much improvement in cognitive functioning is clinically significant? At the present time, there is no consensus on how much improvement in cognitive functioning would be required to be considered clinically important. It is noteworthy, however, that even small improvements with a new medication, averaged over a group of patients, could be the result of large improvements in a subset of the patients in the study. A problem in previous studies is that the patient group size has never been large enough so that subsets of patients who respond to a greater or lesser extent to treatment with these medications could be identified. The identification of these subgroups and their characteristics may have more clinical importance than a statistically significant effect of cognitive enhancement.

Discrimination Between Cognitive Enhancement and Other Clinical Changes

Cognitive impairments in schizophrenia have been found to covary with negative and disorganized symptoms of the illness (61) and to be relatively unassociated with the concurrent severity of positive symptoms. In one switch study that used risperidone as the target compound, improvement in negative symptoms was found to correlate with improvement in executive functioning (22). As a result, it is not known if the improvement in the cognitive domain led to improvement in symptoms, if the two reflect a single dimension of impairment that was generally improved, or if improvement occurred because of some change in other aspects of the illness, such as cooperation. Improvement in test performance due to increased motivation may have very different clinical implications than improved test performance because of changes in basic brain functions due to the administration of novel antipsychotic medications. Therefore, in order to understand the specific patterns of change occurring with treatment, it is important to know the extent to which cognitive change overlaps with changes in other domains, including symptoms and side effects. Unfortunately, many studies of cognitive enhancement neglect to report symptom changes with treatment. Although cognitive impairment has been generally agreed to be a primary, not secondary, feature of schizophrenia, identification of whether treatment changes in cognition are primary or secondary remains an important open question to be addressed in the upcoming literature.

Summary and Conclusions

The notion that novel antipsychotic medications improve cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia is an exciting premise. However, preliminary studies that have given initial support for this notion have been deficient in their methodologies and the extent to which they present critical interpretive information. Most have had so few patients that the identification of the rate of response (i.e., meaningful clinical change) has proven impossible. We have presented a set of issues for the consumer of research that examines the improvement of cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. If readers consider these issues when evaluating the results of future studies, they will be in a better position to evaluate them and understand their implications for the treatment of schizophrenia.

|

|

|

|

Received Oct. 26, 1999; revision received July 12, 2000; accepted July 17, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Harvey, Department of Psychiatry, Box 1229, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 10029; [email protected] (e-mail).The authors thank Alan Breier, M.D., and Estelle Vester-Blockland, M.D., for their comments on earlier versions of this article. Patrick J. Moriarty and Christopher Bowie performed the comprehensive analyses of the previous clinical trial characteristics.

Figure 1. Issues to Consider When Interpreting Studies in Which Cognitive Changes Are Reported in Patients With Schizophrenia Following Novel Antipsychotic Treatment

1. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809–815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Simpson GM, Lindenmayer JP: Extrapyramidal symptoms in patients treated with risperidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:194–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Chouinard G: Effects of risperidone in tardive dyskinesia: an analysis of the Canadian Multicenter Risperidone Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15(suppl 1):36S–44SGoogle Scholar

4. Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Szymanski S, Johns C, Howard A, Kronig M, Bookstein P, Kane JM: Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1744–1752Google Scholar

5. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825–835Link, Google Scholar

7. Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S: Olanzapine versus haloperidol: acute phase results of the North American Double-Blind Olanzapine Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:111–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Buchanan RW, Holstein C, Breier A: The comparative efficacy and long-term effect of clozapine treatment on neuropsychological test performance. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:717–725Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lee MA, Thompson PA, Meltzer HY: Effects of clozapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:82–87Medline, Google Scholar

10. Goldberg TE, Greenberg RD, Griffin SJ, Gold JM, Kleinman JE, Pickar D, Schulz SC, Weinberger DR: The effect of clozapine on cognition and psychiatric symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:43–48Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hagger C, Buckley P, Kenny JT, Friedman L, Ubogy D, Meltzer HY: Improvement in cognitive function and psychotic symptoms in treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 34:702–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Buchanan RW, Holstein C, Breier A: The comparative efficacy and long-term effect of clozapine on neuropsychological test performance. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:717–725Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Zahn T, Pickar D, Haier R: Effects of clozapine, fluphenazine, and placebo on reaction time measures of attention and sensory dominance in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1994; 13:133–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Daniel DG, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE, Pickar D, Lubick LJ, Williams TS: Different side effect profiles of risperidone and clozapine in 20 outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a pilot study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:417–419Link, Google Scholar

15. Grace J, Bellus SP, Raulin ML, Herz ML, Priest BL, Brenner V, Donnelley K, Smith P, Gunn S: Long-term impact of clozapine and psychosocial treatment of psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial functioning. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 4:41–45Google Scholar

16. Hoff AL, Faustman WO, Wieneke M, Espinoza S, Costa M, Wolkowitz O, Csernansky JG: The effects of clozapine on symptom reduction, neurocognitive function, and clinical management in treatment-refractory state hospital schizophrenic inpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 15:361–369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Fuji DE, Ahmed I, Jokumsen M, Compton JM: The effects of clozapine on cognition in treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:240–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Galletly CA, Clark CR, MacFarlane AC, Weber DL: Relationships between changes in symptom ratings, neuropsychological test performance and quality of life in schizophrenic patients treated with clozapine. Psychiatry Res 1997; 72:161–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Meyer-Lindenberg A, Gruppe H, Bauer U, Lis S, Krieger S, Galhoffer B: Improvement of cognitive function in schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine or zotepine: results from a double-blind study. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997; 30:35–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Lindenmeyer J-P, Iskander A, Park M, Apergi FS, Czobor P, Smith R, Allen D: Clinical and neurocognitive effects of clozapine and risperidone in treatment-refractory schizophrenics: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:521–527Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Meltzer HY, McGurk SR: The effects of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:233–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Rossi A, Mancini F, Stratta P, Mattei P, Gismondi R, Pozzi F: Risperidone, negative symptoms, and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: an open study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:40–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Stip E, Lussier I: The effect of risperidone on cognition in patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41(suppl 2):35S–40SGoogle Scholar

24. Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, Kern RS, Mintz J: Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in treatment-resistant schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:799–804Google Scholar

25. Kern RS, Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Wirshing D, McGurk S, Marder SR, Mintz J: Verbal learning in schizophrenia: effects of novel antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:223–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kern RS, Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Wirshing D, McGurk S, Marder SR, Mintz J: Risperidone vs haloperidol on reaction time, manual dexterity, and motor learning in treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:726–732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Kee KS, Kern RS, Marshall BD Jr, Green MF: Risperidone versus haloperidol for perception of emotion in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: preliminary findings. Schizophr Res 1998; 31:159–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McGurk S, Green MF, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Mintz JM: The effects of risperidone vs haloperidol on cognitive functioning in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: the Trail Making Test. CNS Spectrums 1997; 2:61–68Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Serper MR, Chou JCY: Novel neuroleptics improve attentional functioning in schizophrenic patients. CNS Spectrums 1997; 2:56–60Google Scholar

30. Purdon SE, Jones BD, Stip E, Labelle A, Addington D, David SR, Breier A (Canadian Collaborative Group for Research in Schizophrenia): Neuropsychological change in early phase schizophrenia during 12 months of treatment with olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:249–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Sax KW, Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr: Attentional improvement following quetiapine fumarate treatment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1998; 33:151–155Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Google Scholar

33. Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, White L, Davidson M, Mohs RC, Hoblyn J, Davis KL: Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1080–1086Google Scholar

34. Citrome L: New antipsychotic medications: what advantages do they offer? Postgrad Med 1997; 101:207–214Google Scholar

35. Borison RL: Recent advances in the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1997; 4:255–271Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Meltzer HY, Cola PA: The pharmacoeconomics of clozapine: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl 9):161–165Google Scholar

37. Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Ross-Degnan D, Casteris CS, Bollini P: Effects of limiting Medicaid drug-reimbursements benefits on the use of psychotropic agents and acute mental health services by patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:650–655Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Albright PS, Livingstone S, Keegan DL, Ingham M, Shrikhande S, Le Lorier J: Reduction of healthcare resource utilisation and costs following the use of risperidone for patients with schizophrenia previously treated with standard antipsychotic therapy: a retrospective analysis using the Saskatchewan Health linkable databases. Clin Drug Invest 1996; 11:289–299Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Chouinard G, Albright PS: Economic and health state utility determinations for schizophrenic patients treated with risperidone or haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:298–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Meltzer HY, Cola P, Way L, Thompson PA, Bastani B, Davies MA, Snitz B: Cost effectiveness of clozapine in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1630–1638Google Scholar

41. Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Covell NH, Goethe J: Clozapine’s effectiveness for patients in state hospitals: results from a randomized trial. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:683–697Medline, Google Scholar

42. Sevy S, Davidson M: The cost of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:1–3Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Davidson M, Keefe RSE: Cognitive impairment as a target for pharmacological treatment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:123–129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Keefe RSE, Perkins S, Silva SM, Lieberman JA: The effect of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:201–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Farde L, Nordstrom A-L, Wiesel F-A, Pauli S, Halldin C, Sedvall G: Positron emission tomographic analysis of central D1 and D2 dopamine receptor occupancy in patients treated with classical neuroleptics and clozapine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:538–544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Gallhofer B, Bauer U, Lis S, Krieger S, Gruppe H: Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: comparison of treatment with atypical antipsychotic agents and conventional neuroleptic drugs. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1996; 6(suppl 2):13–20Google Scholar

47. Meltzer HY, Burnett S, Bastani B, Ramirez LF: Effects of six months of clozapine treatment on the quality of life of chronic schizophrenic patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:892–897Abstract, Google Scholar

48. Breier A, Buchanan RW, Irish D, Carpenter WT Jr: Clozapine treatment of outpatients with schizophrenia: outcome and long-term response patterns. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:1145–1149Google Scholar

49. Lindström E, Eriksson B, Hellgren A, von Knorring L, Eberhardt G: Efficacy and safety of risperidone in the long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Clin Ther 1995; 17:402–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Quitkin F, Rifkin A, Kaplan JH, Klein DF: Treatment of acute schizophrenia with ultra-high-dose fluphenazine: a failure at shortening time on a crisis-intervention unit. Compr Psychiatry 1975; 16:279–283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Van Putten T, Marder SR, Mintz J: Controlled dose comparison of haloperidol in newly admitted schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:754–761Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Casey DE: Neuroleptic drug-induced extrapyramidal syndromes and tardive dyskinesia. Schizophr Res 1991; 4:109–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Seidman LJ, Pepple JR, Faraone SV: Neuropsychological performance in chronic schizophrenia in response to neuroleptic dose reduction. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:575–584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Davidson M, Harvey PD, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Knobler HY, Losonczy MF, Keefe RSE, Katz S, Frecksa E: Severity of symptoms in chronically institutionalized geriatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:197–207Link, Google Scholar

55. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff?” Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:119–136Google Scholar

56. Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1993Google Scholar

57. Guadagnoli E, Velicer WF: Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol Bull 1988; 103:265–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Obuchowski NA: Sample size calculations in studies of test accuracy. Stat Methods Med Res 1998; 7:371–392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Delucchi K, Bostrom A: Small sample longitudinal clinical trials with missing data: a comparison of analytic methods. Psychol Methods 1999; 4:108–116Crossref, Google Scholar

60. Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris MJ, Jeste DV: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:469–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Addington J, Addington D, Maticka-Tyndale E: Cognitive functioning and positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1991; 4:123–134Crossref, Google Scholar