Six-Year Follow-Up Study of Cognitive and Functional Status Across the Lifespan in Schizophrenia: A Comparison With Alzheimer’s Disease and Normal Aging

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Follow-up studies of cognitive functions of poor-outcome (long-term institutionalized) elderly patients with schizophrenia have demonstrated deterioration over time, while stable cognitive functions over time have been reported for younger, better-outcome schizophrenic patients. This study examined whether cognitive changes in elderly schizophrenic patients with a history of long-term institutional stay extended to institutionalized younger patients. The rate of decline was compared to changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease. METHOD: Patients with schizophrenia (N=107) age 20–80 years were followed over 6 years and assessed with the Clinical Dementia Rating and the Mini-Mental State Examination. The schizophrenic subjects age 50 and older were compared to 136 healthy comparison subjects and 118 Alzheimer’s disease patients age 50 and older who were assessed over a similar follow-up period. RESULTS: There was a significant age group effect on the magnitude of cognitive decline for the schizophrenic subjects, with older subjects experiencing greater levels of decline over the follow-up. Neither the healthy individuals nor the Alzheimer’s disease patients demonstrated similar age-related differences in the magnitude of cognitive change over the follow-up, with healthy comparison subjects showing no change and Alzheimer’s disease patients manifesting decline regardless of age at the initiation of the follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: Institutionalized schizophrenic patients demonstrated an age-related pattern of cognitive change different from that observed for Alzheimer’s disease patients and healthy individuals. The cognitive and functional status of these schizophrenic patients was fairly stable until late life, suggesting that cognitive change may not be occurring in younger patients over an interval as long as 6 years.

Two recent follow-up studies of cognitive and adaptive functions of institutionalized geriatric patients with schizophrenia have demonstrated significant deterioration over follow-up periods averaging 30 months (1, 2). In the first study, which used the Clinical Dementia Rating (3) as the outcome measure, 160 long-term hospitalized geriatric schizophrenic patients were followed (1). Approximately 30% worsened from a baseline of minimal-to-mild cognitive and functional impairment to impairments severe enough to warrant a secondary diagnosis of dementia. The second study found cognitive decline—an average decrease of 3.8 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (4)—over 2.5 years for 57 geriatric schizophrenic patients followed up at a nursing home after discharge from long-term care at a psychiatric hospital (2). Since these observations were made from a cohort of elderly (age >64 years) patients with a history of very poor lifetime functional outcome and long-term institutional care, it is reasonable to question when these change processes occur across the lifespan of poor-outcome schizophrenic patients.

The magnitude of cognitive decline observed in these geriatric patients in relatively brief follow-up periods suggests that cognitive change across the lifespan of institutionalized schizophrenic patients could not be a linear process over the entire illness, as the observed rate of change would have produced substantial cognitive impairment at a far earlier age. Indeed, follow-up studies of first-episode patients have demonstrated stability of neuropsychological deficits early in the course of schizophrenia (5, 6), a finding consistent with much of the literature reporting on younger and middle-aged patients (see Rund [7] for a review). However, these findings of cognitive stability over time do not cancel out the idea that a subset of schizophrenic patients may experience cognitive decline before age 65. Cross-sectional studies of patients with very poor outcome suggest the possibility of a modest decline in cognitive functions that would require many years of follow-up to detect (8), and studies of first-episode patients have found cognitive deficits that could reflect deterioration in cognitive functioning (9). In addition, progressive ventricular enlargement is seen in many different subgroups of nongeriatric patients with schizophrenia, including adolescent patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia (10), a subgroup of first-episode patients (11), and middle-aged patients with a lifetime history of poor functional outcome (12). Therefore, cross-sectional data may implicate slow cognitive change in younger institutionalized schizophrenic patients, while follow-up studies have indicated increased rates of cognitive change in older institutionalized patients (1, 2). It is possible that these differences reflect the phenomenon of normal aging in which changes in cognitive functioning accelerate after age 65 (13–17). However, it is unclear whether the processes of normal aging could account for all the cognitive changes seen in elderly schizophrenic patients because previous follow-up studies of cognitive and functional decline in this population (1, 2) did not utilize prospective comparison groups of healthy individuals. Furthermore, the high prevalence of cognitive and functional impairments consistent with dementia in elderly institutionalized schizophrenic patients (8, 18, 19) raises questions about the contribution of classic neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. Findings from independently collected small (19) and large (20) postmortem series make this conclusion unlikely. Cross-sectional comparisons between the cognitive impairments of Alzheimer’s disease patients and those of geriatric schizophrenic patients have shown quite different profiles of cognitive deficits (21, 22). Longitudinal comparisons of the course of cognitive and functional decline in these two populations are lacking. It would be of interest to determine whether the rate and predictors of cognitive and functional change in these two populations are similar, even if the specific profiles of cognitive deficits are different.

To study the course and predictors of cognitive decline in institutionalized patients with schizophrenia, we conducted a 6-year follow-up study of cognitive and functional status in long-term hospitalized schizophrenic patients ranging in age from 20 to 80 years at baseline. The longitudinal data on the course of cognitive and functional status were compared to data from equivalently aged healthy comparison subjects and patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. This investigation sought to determine if the cognitive and functional changes seen in older poor-outcome patients with schizophrenia extended to younger patients who also have experienced long-term institutional stay. The study included healthy elderly subjects to demonstrate that the cognitive decline seen in elderly poor-outcome schizophrenic patients is not due to simply the effects of normal aging. Alzheimer’s disease comparison subjects were included to determine if the course of cognitive and functional changes in institutionalized patients with schizophrenia was similar to the course of classic neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Method

Subjects

Patients with schizophrenia

The study group of patients with schizophrenia included 57 of the 308 geriatric patients (over age 65) and 50 of the 85 nongeriatric patients reported on by Davidson et al. (8). The subjects from the nongeriatric cohort who could be located received a second assessment at a mean follow-up interval of 6.38 years after their initial assessment. The geriatric patients had received biennial reassessments during a follow-up interval similar to that for the younger subjects (mean interval=5.9 years). Thus, the duration of the follow-up period for the older patients was determined by the duration of follow-up of the younger patients. All schizophrenic subjects met DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia on the basis of an extensive diagnostic work-up, with rigorous exclusion on the basis of alternative neurological or medical factors that might have produced their psychiatric or cognitive symptoms. A complete description of the diagnosis and recruitment of the patients in this research program has been presented previously (8, 21). Information from annual physical examinations was used to eliminate patients who had developed new-onset unstable medical or neurological conditions (e.g., stroke) that might have interfered with their cognitive functioning.

Alzheimer’s disease and healthy comparison subjects

The schizophrenic subjects were compared to a group of 136 healthy comparison subjects and to a group of 118 Alzheimer’s disease patients who had participated in the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (Albert Heyman, M.D., principal investigator [23]), a large-scale study of the characteristics of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The purpose of the study was to standardize the assessment of Alzheimer’s disease by using brief and reliable clinical and neuropsychological measures. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and elderly nondemented comparison subjects were enrolled into the longitudinal study from 21 university medical centers from April 1987 through November 1988. Assessments were obtained at entry and annually thereafter to the extent possible. In our study, we used the database of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (available from Albert Heyman, M.D.) to match patients with schizophrenia to healthy comparison subjects and to patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The comparison and Alzheimer’s disease subjects were chosen on the basis of having prospectively derived data on cognitive functioning over an approximately 6-year follow-up interval. The data selected from the database included results of cognitive assessments and demographic information. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease were selected only if their global Clinical Dementia Rating score was 1.0 (mild, but definite dementia) or less at the time of their first assessment. This criterion was used to identify a group who would be likely to show characteristic patterns of cognitive and functional decline for the entire 6-year period, without reaching a “floor” level of functioning.

Assessments

The subjects were assessed with the Clinical Dementia Rating (3), a staging scale for the severity of cognitive and functional impairments in dementia. The scale assesses impairment in six categories of functioning (memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care) on a graduated scale (0=absent, 0.5=questionable, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, and 4=profound). From the outset of our schizophrenia follow-up study, we completed the Clinical Dementia Rating by using the same instructions and procedures as were used in the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease project. Raters evaluated information from patients’ charts and the results of a neuropsychological assessment and other focused rating scales and then generated Clinical Dementia Rating item and global scores by using formal rating criteria. The interrater reliability of the Clinical Dementia Rating in patients with schizophrenia (24) was high (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.86).

Clinical symptoms were rated only in the schizophrenic patients by using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (25). The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale contains 30 items; seven of the 30 items rate positive symptoms, seven rate negative symptoms, and 16 assess “general psychopathology.” The rating procedures and the reliability of the assessments in this study group of schizophrenic patients have been described previously (8). Reliability was maintained through regular consensus meetings to avoid drift in ratings.

In addition, the subjects’ cognitive functioning was assessed with the MMSE, a screening tool that allows quantitative assessment of the severity of cognitive impairment associated with dementia (4). The MMSE is scored on a 30-point scale and assesses several domains of cognitive function, including word list registration and recall, attention, calculation, language, and visual construction. The instrument has shown extremely high levels of interrater reliability and test-retest reliability in this group of patients with schizophrenia (24, 26).

Analyses

The three subject groups (patients with schizophrenia, healthy subjects, and subjects with Alzheimer’s disease) were divided into four groups on the basis of age at the baseline assessment (50–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75–80 years). Additional data were available for the schizophrenic patients in the 20–39-year and 40–49-year age groups. A dichotomous variable was created from the Clinical Dementia Rating scores to facilitate the determination of new-onset cognitive and functional decline. In this analysis, patients were grouped on the basis of their baseline Clinical Dementia Rating scores. Following a previously used convention (1), we considered patients with baseline scores of 1.0 (mild cognitive and functional impairment) or less to be less impaired, and these patients were the focus of the follow-up to determine the course of worsening in their cognitive and functional status. In normal individuals with a history of adequate cognitive functioning and functional adjustment, a score of 1.0 would necessarily reflect a previous decline in functioning. However, in patients with schizophrenia, cognitive functioning at the time of the first episode is often grossly impaired (5, 6), and a score of 1.0 would be possible at that time. Worsening in global functional status was defined as having a Clinical Dementia Rating score at a subsequent follow-up of 2.0 (moderate cognitive and functional impairment) or greater. Patients with a baseline score of 2.0 or more were not examined for decline in functioning because these patients already met criteria for significant cognitive and functional impairment and because it is not clear if changes from a score of 2.0 to 3.0 (severe cognitive and functional impairment) are as significant as changes from 1.0 or less to 2.0. Since the Clinical Dementia Rating is an ordinal scale, the increment in impairment from 1.0 to 2.0 is defined differently from the increment from 2.0 to 3.0. The ordinal nature of the scale also precludes the use of statistical tests of the significance of the difference of average scores.

Proportional risk rates for cognitive and functional decline over the follow-up were calculated separately for the schizophrenic, healthy, and Alzheimer’s disease subjects within each age group. The number of subjects with a decline (designated by a progression from a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating score of 1.0 or less to a follow-up score of 2.0 or more) within each age group was divided by the total number of subjects. Proportional risk rates for the schizophrenic, healthy, and Alzheimer’s disease subjects were then compared by using z tests for the significance of the difference between proportions.

To quantify more precisely the extent of global cognitive decline, change scores on the MMSE were calculated for each subject over the follow-up interval. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a 4-by-3 factorial design was employed to examine effects of the interaction between age group and subject group (healthy, schizophrenic, Alzheimer’s disease) on the magnitude of MMSE change over the follow-up (excluding the younger schizophrenic patients). Simple effects tests were then employed to determine the significance of the main effect of age group on the interval change score for the MMSE within each subject group separately.

Results

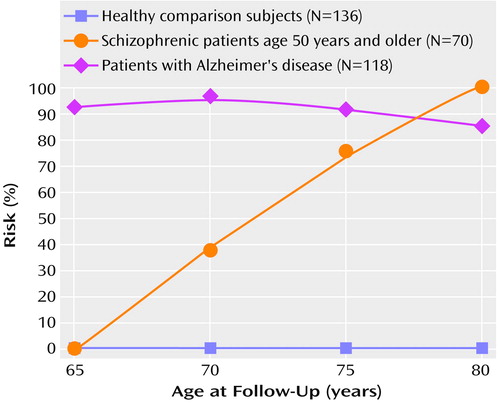

Table 1 shows the number of healthy, schizophrenic, and Alzheimer’s disease subjects with follow-up data and the mean follow-up interval and years of education in each age group. The mean follow-up intervals for the overall subject groups were 6.13 years (SD=0.25) for the healthy comparison group, 5.91 years (SD=0.94) for the schizophrenic group, and 5.24 years (SD=0.67) for the Alzheimer’s disease group, a significant difference among groups (F=81.44, df=2, 359, p<0.001). Post hoc comparisons showed that the Alzheimer’s disease group had a significantly shorter follow-up interval than the schizophrenic group and the healthy comparison group (p<0.001, Scheffé, for both comparisons), but there was no difference between the schizophrenic and healthy comparison groups (p=0.91, Scheffé). Mean levels of education differed significantly among the three groups (F=63.13, df=2, 358, p<0.01); the healthy comparison subjects were the best educated (mean=14.6 years, SD=2.9), followed by the Alzheimer’s disease subjects (mean=13.5 years, SD=3.3) and the schizophrenic subjects (mean=10.4 years, SD=2.7). ANOVAs also demonstrated a significant effect of age group on the level of education within the schizophrenic group (F=5.33, df=5, 101, p<0.001) and the Alzheimer’s disease group (F=4.98, df=3, 114, p=0.003), with the younger patients being better educated than the older patients. Table 2 presents mean baseline MMSE scores by age group at baseline for the healthy comparison, schizophrenic, and Alzheimer’s disease subjects and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores for the schizophrenic subjects. ANOVA demonstrated significant differences in baseline MMSE scores among the three subject groups (F=147.21, df=2, 359, p<0.001). Post hoc comparisons showed that the schizophrenic group had a significantly lower baseline MMSE score than either the healthy comparison group or Alzheimer’s disease group (p<0.001, Scheffé, for both comparisons). Hence, subsequent analyses controlled for these differences.

Since only the schizophrenic subjects who were available to be reassessed after the average 6-year follow-up interval were included in the analysis of cognitive change, there is the possibility that the magnitude of cognitive decline was influenced by the noninclusion of subjects who had not, or could not, complete 6 years of follow-up. Therefore, we compared the baseline characteristics of the schizophrenic patients who were and were not reassessed at the follow-up. Subjects who were not followed up were divided into two groups: those who died and those who were lost to follow-up owing to relocation, refusal, or development of a new medical illness potentially affecting cognitive functioning. Forty-eight of the 308 geriatric schizophrenic patients in the original cohort (8) had died, and 201 were lost to follow-up. The schizophrenic subjects who were followed up did not differ in level of education, baseline MMSE score, and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale positive and negative symptom scores from those who were lost to follow-up (t<1.5, df=258, p>0.1 for all comparisons) or from those who had died (t<1.5, df=105, p>0.1 for all comparisons).

The risk for cognitive and functional decline over the follow-up interval in each age group was calculated for the subjects with higher functioning at baseline (Clinical Dementia Rating <2.0) within each of the three subject groups. At baseline, 45 of the 107 schizophrenic subjects (all over the age of 65) met criteria for significant cognitive and functional impairment (Clinical Dementia Rating ≥2.0), leaving 62 subjects whose ratings could be followed for subsequent decline in functioning. At baseline, because of the selection processes, all 136 healthy comparison subjects and 118 of the Alzheimer’s disease subjects had baseline Clinical Dementia Rating scores <2.0.

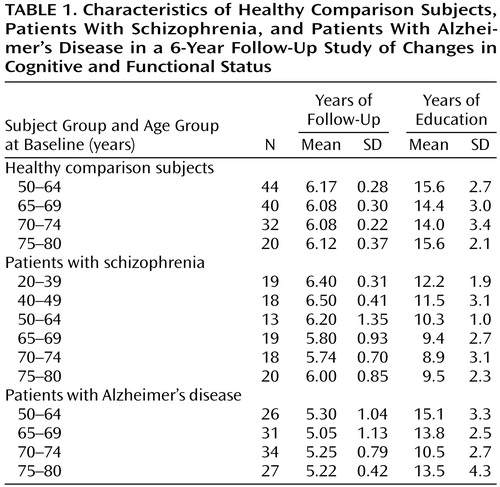

Figure 1 illustrates the proportional risk for cognitive and functional decline, as defined by an increase in Clinical Dementia Rating scores to ≥2.0, as a function of age for the schizophrenic subjects, including the youngest patients, over the entire follow-up. Below age 65 the proportional risk for cognitive and functional decline was negligible (e.g., 5.7% before age 40 and 0% between ages 40 and 65). Above age 65, the proportional risk began to rise such that between ages 65 and 70, the risk was 37.5%; between ages 70 and 75, it was 75.0%; and between ages 75 and 80, it was 100%.

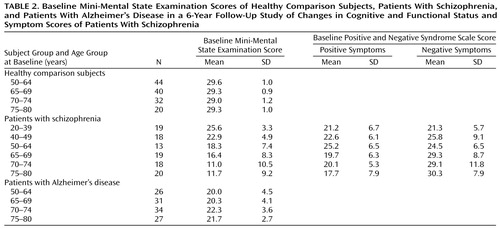

The age-associated proportional risk rates of cognitive and functional decline over the follow-up interval for the schizophrenic subjects over the age of 50 were then compared with the rates for the same age groups of healthy comparison and Alzheimer’s disease subjects by using z tests for the significance of the difference between proportions (Figure 2). From age 50 to age 65 the schizophrenic subjects showed no significant differences from the healthy comparison subjects in proportional risk rates of cognitive and functional decline (z=0, p>0.1). By age 70 the schizophrenic subjects demonstrated consistent significantly greater proportional risk rates of cognitive and functional decline over the follow-up interval compared to healthy subjects (z>2.00, p<0.001, for all comparisons). Compared with the Alzheimer’s disease subjects, the schizophrenic subjects demonstrated significantly lower proportional risk rates for cognitive and functional decline over the follow-up (z>2.00, p<0.001, for all comparisons) until age 75, when the rates did not differ (z=1.25, p=0.21).

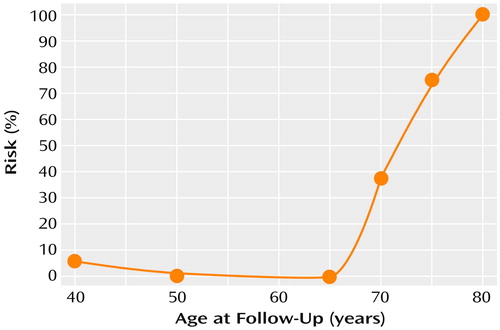

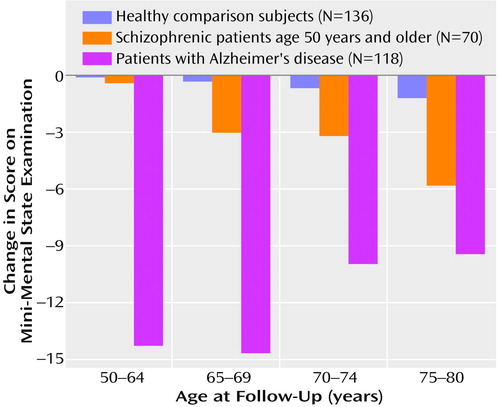

The next set of analyses investigated the effect of the interaction of age and subject group on MMSE interval change scores (Figure 3). Since mean level of education and baseline MMSE scores were different between subject groups, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the number of years of education and baseline MMSE scores as covariates, was used for these analyses. The results showed that the interaction of age and subject group had a significant effect on MMSE interval change scores (F=4.76, df=6, 199, p<0.001). Baseline MMSE scores exerted a significant covariate effect (t=3.9, p<0.001), whereas level of education did not (t=0.66, p=0.51) (df not available for covariate). To determine which subject group showed the significant main effect of age on MMSE change scores, simple effects tests were used. These analyses demonstrated significant age effects on MMSE interval change scores for the schizophrenic subjects (F=6.04, df=6, 199, p=0.02), with the older schizophrenic subjects showing greater decline in MMSE scores over the follow-up than the younger subjects. No such age effect on MMSE change scores was seen for the healthy comparison group (F=0.18, df=6, 199, p=0.16) or the Alzheimer’s disease patients (F=2.7, df=6, 199, p=0.19). Planned comparisons with the experiment-wise error term within the schizophrenic group demonstrated that the age effect on MMSE interval change scores was significant when subjects were split into two age groups: 50–64 years and 65–80 years (F=10.99, df=2, 199, p=0.01).

Since the older schizophrenic patients demonstrated higher levels of negative symptoms (Table 2), it is possible that the magnitude of cognitive decline observed in the older schizophrenic subjects was overestimated. Therefore, the ANCOVA examining the effect of age on MMSE interval change scores was recalculated by using baseline and change in negative symptom scores over the interval as the covariates. The main effect of age on MMSE score decline remained significant after covarying for baseline (F=3.7, df=5, 83, p=0.005) and change scores (F=3.17, df=5, 83, p=0.01) on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total negative syndrome subscale.

Discussion

The study results show different age-related patterns of cognitive change in institutionalized schizophrenic patients compared with Alzheimer’s disease patients and healthy comparison subjects over age 50. The results also demonstrate that the progressive cognitive decline experienced by poor-outcome schizophrenic patients is not a linear process across the lifespan and that the rate of cognitive change accelerates beyond age 65. These findings may help explain the variations in neuropsychological findings from longitudinal and cross-sectional studies (see reference 27 for review). As has been demonstrated previously, the neuropsychological functions of schizophrenic patients are fairly stable early in the course of illness (5, 6), leading some researchers to conclude that cognitive functions are stable over the entire lifespan (7). However, longitudinal studies of truly elderly patients with schizophrenia are actually fairly rare and have been limited to poor-outcome patients (1, 2). In this study, we examined a younger group of patients with a very poor prognosis who were selected for their similarity to the geriatric patients, who were more cognitively and functionally impaired at baseline than the younger patients typically included in previous studies. Despite this matching strategy, we failed to detect cognitive change in the younger patients with schizophrenia. Hence, even in poor-outcome schizophrenic patients, progressive cognitive change is not apparent in younger individuals. Thus, the results of this study suggest that cognitive decline over a follow-up as long as 6 years in poor-outcome patients with schizophrenia is limited to those over age 65.

While an interaction between age at the beginning of the follow-up period and extent of cognitive change over an ensuing 6-year period was observed for the schizophrenic subjects, the Alzheimer’s disease subjects experienced a precipitous drop in cognitive performance over the follow-up regardless of baseline age. This is consistent with other data demonstrating that the annual rate of cognitive change does not significantly vary with age at onset in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (28–30). Longitudinal studies of Alzheimer’s disease patients demonstrate an average annual rate of decline on the MMSE between 2 and 5 points (31–36), with an average of 3 points per year over the typical 10-year course of the illness. This annual rate of decline is markedly greater than that occurring, on average, for the oldest schizophrenic patients in this study, who had an average decline of 1 point per year over the 6-year follow-up study. These data suggest differences in both the lifetime course of cognitive and functional decline and in the annualized amount of decline between patients with schizophrenia and those with Alzheimer’s disease.

To help disentangle the influence of normal aging on the cognitive decline of schizophrenia, a healthy comparison group was examined in this study. While the healthy group had a slight cognitive change with advancing age, the change did not reach statistical significance nor was its magnitude close to that observed for the schizophrenic group. This finding replicates the findings of population studies in which a modest degree of cognitive decline is observed in normal elderly persons (15, 37–40). For example, the Baltimore area Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (15), with 1,488 participants, found a mean decline on the MMSE of 2.62 points and 3.23 points over an 11.5-year follow-up period for normal subjects aged 61–70 years and aged ≥71 years, respectively. The schizophrenic patients in our study within the same age groups demonstrated prorated annual rates of MMSE decline that were 2.3 and 3.5 times faster, respectively.

Other factors that may have contributed to the observed differences in changes in cognitive and functional status between the subject groups include level of motivation, educational background, exposure to neuroleptics and other somatic treatments, selective subject attrition, and test-retest fluctuations. Motivation differences between groups were unlikely to have produced the observed results because the poor-outcome schizophrenic patients had previously demonstrated a distinct pattern of differential cognitive deficits, compared to both patients with Alzheimer’s disease (20) and healthy subjects (41), rather than the global suppression of all domains of cognitive functioning that might reflect lack of motivation.

Prior treatment with leukotomy, insulin coma, and ECT, as well as current exposure to neuroleptic medication, have been shown to have no adverse effect on current cognitive functioning as measured by the MMSE at the baseline assessment of these patients (8). Differential loss of potentially available patients is not a probable source of overestimation of cognitive decline because the group who did not complete the 6-year follow-up did not differ significantly from those who did in baseline levels of education, symptoms, or cognitive functioning. Furthermore, previous longitudinal studies of the evolution of cognitive decline in older persons have demonstrated that ignoring missing data owing to attrition leads, if anything, to an underestimation of the true extent of cognitive decline (42).

Since the schizophrenic group was significantly less educated than either the healthy comparison group or Alzheimer’s disease group, especially among the oldest subjects, the effect of education was also considered. To examine the effects of age and education, multiple sets of normative data have been produced for the MMSE (43–47). Age- and education-specific reference values for the MMSE from 7,754 subjects (43) demonstrated that normal persons with even lower levels of education (grade 5–8) than the schizophrenic subjects in this study had consistently higher MMSE scores in the age ranges of 65–69 years (26.9 versus 16.4), 70–74 years (27.0 versus 11.0), and 75–79 years (26.4 versus 11.7).

Finally, the question of whether the MMSE is able to reflect true cognitive decline over time needs to be addressed. It is worth noting that test-retest reliability estimates over short intervals have generally been quite high for the MMSE, even in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Studies with more extended test-retest intervals (1–2 years) with cognitively intact subjects have demonstrated relatively small amounts of change over the follow-up interval; these changes were usually within two points and were not statistically significant (46). This level of test-retest fluctuation is considerably smaller than the amount of MMSE change observed in the older schizophrenic subjects and could not account for all the change. In fact, low scorers, such as the patients with schizophrenia in this study, would be expected to improve with retesting because of regression to the mean and possible practice effects. This would have reduced the magnitude of the decline detected at a reassessment.

It may be argued that the results of this study are limited because of the use of gross measures of cognitive functions, such as the MMSE and the Clinical Dementia Rating. Conceivably, a more extensive battery may have found more subtle changes. However, the relative insensitivity of the MMSE and the Clinical Dementia Rating may make the findings of cognitive change much more clinically relevant. Furthermore, while individual subscores within specific, more sophisticated cognitive tests are certainly useful because they give an indication of an individual’s cognitive profile, these psychometric tests may be limited by insensitivity owing to floor effects in severely impaired schizophrenic patients. For example, patients may score 0 on a specific cognitive test and hence no longer produce valid data, yet continue to progress in severity in a manner detectable by the Clinical Dementia Rating.

Another limitation of this study is that the schizophrenic subjects had been long-term institutionalized and clearly differed from patients who live independently in the community and who are more likely to participate in studies. Although clearly not in the majority, the long-term institutionalized subset of patients with schizophrenia still represents a fairly large cohort. Approximately 200,000 geriatric schizophrenic patients reside in nursing homes (47–49) that primarily serve custodial care functions (50), and these patients have severe cognitive and functional deficits (51, 52). More than a decade ago, it was estimated that nursing home care accounted for 29% of national expenditures on behalf of treatment of mentally ill persons (53). In view of the consequences of cognitive impairment for the quality of life, level of functional disability, and mortality of patients with schizophrenia, the evolution of severely impaired cognitive functioning in subsets of schizophrenic patients deserves continued attention. Should this issue remain ignored and treatments underinvestigated, then long-term institutionalization and nursing home placement will continue to be a costly part of the mental health care system.

|

|

Received June 15, 2000; revision received Jan. 9, 2001; accepted Feb. 19, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; and Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, Brentwood, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Friedman, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, Box 1230, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-46436 (Dr. Davidson) and by the Assessment Core (Dr. Harvey, principal investigator) of grant MH-56083 to the Mount Sinai Geriatric Schizophrenia Clinical Research Center (Dr. Davis, principal investigator). The authors thank Albert Heyman, M.D., for contribution of longitudinal data from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease project.

Figure 1. Proportional Risk for Cognitive and Functional Declinea Over a 6-Year Follow-Up Period Among Patients With Schizophrenia (N=107)

aDecline defined by an increase in Clinical Dementia Rating score from <2.0 (mild or no impairment) at baseline to ≥2.0 (moderate or more severe impairment) at follow-up. All patients had mild or no impairment at baseline.

Figure 2. Proportional Risk for Cognitive and Functional Declinea Over a 6-Year Follow-Up Period Among Healthy Comparison Subjects, Patients With Schizophrenia, and Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease

aDecline defined by an increase in Clinical Dementia Rating score from <2.0 (mild or no impairment) at baseline to ≥2.0 (moderate or more severe impairment) at follow-up. All patients had mild or no impairment at baseline.

Figure 3. Change in Score on the Mini-Mental State Examination Over a 6-Year Follow-Up Period Among Healthy Comparison Subjects, Patients With Schizophrenia, and Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease

1. Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, Parrella M, White L, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL: Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:32-40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Mohs RC, Davidson M, Davis KL: Convergence of cognitive and adaptive decline in late-life schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1999; 35:77-84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Berg L: Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:637-639Medline, Google Scholar

4. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Gold S, Arndt S, Nopoulos P, O’Leary DS, Andreasen NC: Longitudinal study of cognitive function in first-episode and recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1342-1348Google Scholar

6. Hoff AL, Sakuma M, Wieneke M, Horon R, Kushner M, DeLisi LE: Longitudinal neuropsychological follow-up study of patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1336-1341Google Scholar

7. Rund BR: A review of longitudinal studies of cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:425-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Davidson M, Harvey PD, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Knobler HY, Losconczy MF, Keefe RS, Katz S, Frecska E: Severity of symptoms in chronically institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:197-207Link, Google Scholar

9. Bilder RM, Lipschultz-Broch L, Reiter G, Geisler SH, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman JA: Intellectual deficits in first-episode schizophrenia: evidence for progressive deterioration. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:437-448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rapoport JL, Giedd J, Kumra S, Jacobsen L, Smith A, Nelson LJ, Hamburger S: Childhood onset schizophrenia: progressive ventricular change during adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:897-903Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. DeLisi LE, Sakuma M, Tew W, Kushner M, Hoff AL, Grimson R: Schizophrenia as a chronic active brain process: a study of progressive brain structural change subsequent to the onset of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 1997; 74:129-140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Davis KL, Buchsbaum MS, Shihabuddin L, Spiegel-Cohen J, Metzger M, Frecska E, Keefe RS, Powchik P: Ventricular enlargement in poor outcome schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:783-793Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cullum CM, Thompson LL, Heaton RK: The use of the Halstead-Reitan test battery with older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 1989; 5:595-610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Brayne C, Spiegelhalter DJ, Dufouil C, Chi LY, Dening TR, Paykel ES, O’Connor DW, Ahmed A, McGee MA, Huppert FA: Estimating the true extent of cognitive decline in the old old. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:1283-1288Google Scholar

15. Lyketsos CG, Chen L-S, Anthony JC: Cognitive decline in adulthood: an 11.5-year follow-up of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:58-65Link, Google Scholar

16. Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, McDonald-Miszczak L, Dixon RA: Short-term longitudinal change in cognitive performance in later life. Psychol Aging 1992; 7:571-584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Johansson B, Zarit SH, Berg S: Changes in cognitive functioning of the oldest old. J Gerontol 1992; 47:75-80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Harvey PD, Leff J Trieman N, Anderson J, Davidson M: Cognitive impairment and adaptive deficit in geriatric chronic schizophrenic patients: a cross national study in New York and London. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:1001-1007Google Scholar

19. Arnold SE, Gur RE, Shapiro RM, Fisher KR, Moberg PJ, Gibney MR, Gur RC, Blackwell P, Trojanowski JQ: Prospective clinicopathologic studies of schizophrenia: accrual and assessment of patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:731-737Link, Google Scholar

20. Purohit DP, Perl DP, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL: Alzheimer disease and related neurodegenerative diseases in elderly patients with schizophrenia: a postmortem neuropathology of 100 cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:205-211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Davidson M, Harvey P, Welsh KA, Powchik P, Putnam KM, Mohs RC: Cognitive functioning in late-life schizophrenia: a comparison of elderly schizophrenic patients and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1274-1279Google Scholar

22. Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris J, Jeste DV: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:469-476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, Clark C: The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD), part I: clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1989; 39:1159-1165Google Scholar

24. Harvey PD, Davidson M, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Mohs RC: Assessment of dementia in elderly schizophrenics with structured rating scales. Schizophr Res 1992; 7:85-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kay SR: Positive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1991Google Scholar

26. Harvey PD, White L, Parrella M, Putnam KM, Kincaid MM, Powchik P, Mohs RC, Davidson M: The longitudinal stability of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: Mini-Mental State scores at one and two-year follow-ups in geriatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:630-633Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Friedman JI, Harvey PD, Kemether E, Byne W, Davis KL: Cognitive and functional changes with aging in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:921-928Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Stern RG, Mohs RC, Davidson M, Schmeidler J, Silverman J, Kramer-Ginsberg E, Searcey T, Bierer L, Davis KL: A longitudinal study of Alzheimer’s disease: measurement, rate, and predictors of cognitive deterioration. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:390-396Link, Google Scholar

29. Katzman R, Brown T, Thal LJ, Fuld PA, Aronson M, Butters N, Klauber MR, Wiederholt W, Pay M, Renbing X, Ooi WL, Hofstetter R, Terry RD: Comparison of rate of annual change of mental status score in four independent studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1988; 24:384-389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Thal LJ, Grundman M, Klauber MR: Dementia: characteristics of a referral population and factors associated with progression. Neurology 1988; 38:1083-1090Google Scholar

31. Teng EL, Chui HC, Schneider LS, Metzger LE: Alzheimer’s dementia: performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987; 55:96-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Morris JC, Edland S, Clark C, Galasko D, Koss E, Mohs R, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD), part IV: rates of cognitive change in the longitudinal assessment of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1993; 43:2457-2465Google Scholar

33. Becker JT, Huff FJ, Nebes RD, Holland A, Boller F: Neuropsychological function in Alzheimer’s disease: pattern of impairment and rates of progression. Arch Neurol 1988; 45:263-268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Salmon DP, Thal JL, Butters N, Heindel WC: Longitudinal evaluation of dementia of the Alzheimer type: a comparison of 3 standardized mental status examinations. Neurology 1990; 40:1225-1230Google Scholar

35. Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R: Progression of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39:39-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. O’Connor DW, Pollitt PA, Hyde JB, Miller ND, Fellowes JL: The progression of mild idiopathic dementia in a community population. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39:246-251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Grimby A, Berg S: Stressful life events and cognitive functioning in late life. Aging (Milano) 1995; 7:35-39Medline, Google Scholar

38. Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, McDonald-Miszczak L, Dixon RA: Short-term longitudinal change in cognitive performance in later life. Psychol Aging 1992; 7:571-584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Johansson B, Zarit SH, Berg S: Changes in cognitive functioning of the oldest old. J Gerontol 1992; 47:75-80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Farmer ME, Kittner SJ, Rae DS, Bartko JJ, Regier DA: Education and change in cognitive function: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Ann Epidemiol 1995; 5:1-7Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Harvey PD, Moriarty PJ, Friedman JI, Parrella M, White L, Mohs RC, Davis KL: Differential preservation of cognitive functions in geriatric patients with lifelong chronic schizophrenia: less impairment in reading scores compared to other skill areas. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:962-968Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Brayne C, Spiegelbalter DJ, Dufouil C, Chi Lin-Yang, Dening TR, Paykel ES, O’Connor DW, Ahmed A, McGee MA, Huppert FA: Estimating the true extent of cognitive decline in the old old. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:1283-1288Google Scholar

43. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF: Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA 1993; 269:2386-2391Google Scholar

44. Heeron TJ, Lagaay AM, Beek WCA, Rooymans HGM, Hijmans W: Reference values for the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in octo- and nonagenarians. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38:1093-1096Google Scholar

45. Bravo G, Hebert R: Age- and education-specific reference values for the Mini-Mental and modified Mini-Mental State Examinations derived from a non-demented elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:1008-1018Google Scholar

46. Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ: The Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:922-935Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Strahan GW: Prevalence of selected mental disorders in nursing and related care homes, in Mental Health, United States, 1990: DHHS Publication ADM 90-1708. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1990Google Scholar

48. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977-986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Gurland BJ, Cross PS: Epidemiology of psychopathology in old age. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1982; 98:478-486Google Scholar

50. Bootzin RR, Shadish WR, McSweeny AJ: Longitudinal outcomes of nursing home care for severely mentally ill patients. J Social Issues 1989; 45:31-48Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, White L, Davidson M, Mohs RC, Hoblyn J, Davis KL: Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1080-1086Google Scholar

52. Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM: A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophr Res 1997; 27:181-190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Frisman L, McGuire T: The economics of long-term care for the mentally ill. J Soc Issues 1989; 45:121-123Crossref, Google Scholar