Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of the Cavum Septi Pellucidi in Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging was used to evaluate the prevalence of the cavum septi pellucidi (CSP) in 79 normal subjects and 86 patients with schizophrenia. METHOD: The CSP was assessed by counting the number of consecutive coronal 1-mm slices containing the CSP. A CSP equal to or greater than 6 mm in length was defined as large. RESULTS: The CSP was found in 74.4% of the patients and 74.7% of the normal subjects, a nonsignificant difference. No difference between groups was found in the prevalence of a large CSP. CONCLUSIONS: The findings support the idea that a small CSP is a normal anatomical variant. More cases of a large CSP are needed to elucidate the implications of this abnormality in schizophrenia.

Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and postmortem brain studies have reported a wide variance from 0.1% to 85% in the prevalence of the cavum septi pellucidi (CSP) in normal adults (1–11). A wide variance in the prevalence of the CSP—from 16% to 77%—has also been reported in patients with schizophrenia (2–11). Several MRI studies have reported a higher prevalence of the CSP in patients with schizophrenia than in normal subjects (2, 4, 5, 7, 8). Furthermore, recent MRI studies have found that patients have a higher prevalence of a large CSP than comparison subjects, suggesting that this feature may reflect neurodevelopmental abnormalities (3, 9, 11).

In the study reported here, we obtained three-dimensional MRI scans with a high-resolution voxel size of 1.0×1.0×1.0 mm for 86 patients with schizophrenia and 79 normal subjects and compared the prevalence of the CSP in the two groups.

Method

Eighty-six right-handed patients (46 men and 40 women; mean age=29.3 years, SD=8.8) who met the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia were recruited from the inpatient and outpatient clinics of the Department of Neuropsychiatry, Toyama Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital. The mean age at the onset of illness was 23.5 years (SD=6.8), and the mean duration of illness was 6.1 years (SD=6.3). Eighty-two patients were receiving neuroleptic medication (mean haloperidol equivalent dose=9.8 mg/day, SD=8.2). Sixty-eight were receiving typical neuroleptics, 14 were receiving atypical neuroleptics, and 71 were receiving additional anticholinergic medications. The mean duration of treatment was 4.3 years (SD=4.4). The normal comparison subjects were 79 right-handed volunteers (44 men and 35 women; mean age=24.0 years, SD=6.1). The MMPI was completed for each normal subject, and subjects with a T score >70 on any MMPI clinical subscale were excluded. All subjects were physically healthy, and none had a history of head trauma, serious medical or surgical illness, or substance abuse. The mean age of the patients was significantly higher than that of the comparison subjects (t=4.49, df=163, p<0.01). The purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the patients and the comparison subjects, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

MRI was performed with a 1.5-T Siemens Magnetom Vision scanner. A three-dimensional, fast low angle shot imaging sequence was used to obtain T1-weighted images with a slice thickness of 1.0 mm in the sagittal plane (TE=5 msec, TR=24 msec, flip angle=40°, number of excitations=1, field of view=25.6 cm, matrix=256×256). The reconstructed coronal slices perpendicular to the intercommissural line were 1 mm-thick and consisted of 64 contiguous slices through the entire septum pellucidum. Hard copies of the films were combined in random order and visually inspected by two raters who were blind to the subjects’ diagnoses. For the assessment of the CSP, the number of coronal slices where a cavum was seen was counted (3, 11). Since the images were 1 mm-thick without gaps, the rating was a reflection of the actual anterior-to-posterior length of the cavum. A CSP equal to or greater than 6 mm in length was defined as large. The Pearson correlation coefficient for interrater reliability of the two raters was 0.99 for ratings of the CSP in the 165 subjects in this study and an additional 34 subjects with dementia or other illnesses.

Chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact tests when expected cell sizes were less than five, were used for statistical analysis of the frequency of the CSP. Correlations between ratings of the CSP and clinical variables were assessed with Spearman’s rank-order correlation. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

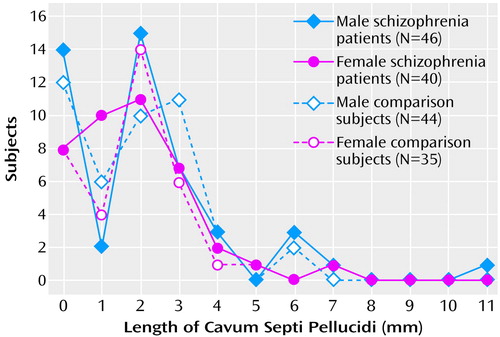

Figure 1 shows the frequency of the CSP by size (length in mm). The prevalence of the CSP was 74.4% (64 of 86) in the patients with schizophrenia and 74.7% (59 of 79) in the comparison subjects, not a significant difference (χ2=0.002, df=1, p=0.97). When the prevalences were compared separately in the male and female subjects, no significant group differences were revealed (male subjects: 69.6% [32 of 46 patients] versus 72.7% [32 of 44 comparison subjects], χ2=0.11, df=1, p=0.74; female subjects: 80.0% [32 of 40 patients] versus 77.1% [27 of 35 comparison subjects], χ2=0.09, df=1, p=0.76). In both the patient group and the normal comparison group, there was no significant sex difference in the prevalence of the CSP.

The prevalence of a large CSP did not differentiate the schizophrenia group from the comparison group (7.0% [6 of 86 patients] versus 3.8% [3 of 79 comparison subjects]) (p=0.29, Fisher’s exact test). The prevalence of a large CSP did not differ between groups in separate comparisons of the male and female subjects (male subjects: 10.9% [5 of 46 patients] versus 4.5% [2 of 44 comparison subjects], p=0.24, Fisher’s exact test; female subjects: 2.5% [1 of 40 patients] versus 2.9% [1 of 35 comparison subjects], p=0.72, Fisher’s exact test). In both the patient group and the comparison group, there were no statistically significant sex differences in the prevalence of a large CSP.

In the patients with schizophrenia, ratings of the CSP were not correlated significantly with age at onset (r=0.11, N=86, p=0.31) or duration of illness (r=–0.02, N=86, p=0.85).

Discussion

This study is strengthened by the larger size of the study group and the use of thinner MRI slices, compared with those in some previous studies (2–11). Similarly high prevalences of the CSP were shown in both the patients with schizophrenia and the normal comparison subjects. These findings are in agreement with those in three-dimensional MRI studies that have used thinner contiguous slices (3, 11). The high prevalence of the CSP in the comparison subjects in this study further supports the idea that the CSP is a normal anatomical variant (1, 3, 8).

In contrast, a large CSP has been implicated in neurodevelopmental abnormalities (1, 12). Also in schizophrenia, MRI studies have reported an increased prevalence of a large CSP, which has been referred to as a marker of abnormal development (3, 9, 11). Correlations of a large CSP with IQ decrement (13) and poor prognosis (10) in schizophrenia have been reported. The present study did not find a higher prevalence of a large CSP (in terms of length) in the patients. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for the frequency of a large CSP were –0.4% to 8.0% and 1.6% to 12.4% in the comparison subjects and the schizophrenia patients, respectively. These confidence intervals suggest that, even if the prevalences differed between groups, the difference was relatively small (i.e., less than 13%). However, our results do not completely eliminate possible implications of an abnormal CSP in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. A larger number of patients with a large CSP need to be examined to explore the relationship of an abnormal CSP with other structural abnormalities and with the cognitive and clinical characteristics of patients with schizophrenia.

Received Oct. 31, 2000; revisions received March 13 and April 12, 2001; accepted April 18, 2001. From the Departments of Neuropsychiatry and Radiology, Toyama Medical and Pharmaceutical University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hagino, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Toyama Medical and Pharmaceutical University, 2630 Sugitani, Toyama 930-0194, Japan; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Length of the Cavum Septi Pellucidi (CSP) in Male and Female Patients With Schizophrenia (N=86) and Normal Comparison Subjects (N=79)a

aNo significant differences in prevalence of the CSP between male patients and male comparison subjects and between female patients and female comparison subjects. No significant sex differences in prevalence of the CSP in either the patient group or the comparison group.

1. Sarwar M: The septum pellucidum: normal and abnormal. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1989; 10:989-1005Medline, Google Scholar

2. Degreef G, Bogerts B, Falkai P, Greve B, Lantos G, Ashtari M, Lieberman J: Increased prevalence of the cavum septum pellucidum in magnetic resonance scans and post-mortem brains of schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res 1992; 45:1-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Nopoulos P, Swayze V, Flaum M, Ehrhardt JC, Yuh WT, Andreasen NC: Cavum septi pellucidi in normals and patients with schizophrenia as detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:1102-1108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Degreef G, Lantos G, Bogerts B, Ashtari M, Lieberman J: Abnormalities of the septum pellucidum on MR scans in first-episode schizophrenic patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1992; 13:835-840Medline, Google Scholar

5. Scott TF, Price TP, George MS, Brillman J, Rothfus W: Midline cerebral malformations and schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:287-293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jurjus GJ, Nasrallah HA, Olson SC, Schwarzkopf SB: Cavum septi pellucidum in schizophrenia, affective disorder and healthy controls: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychol Med 1993; 23:319-322Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Shoiri T, Oshitani Y, Kato T, Murashita J, Hamakawa H, Inubushi T, Nagata T, Takahashi S: Prevalence of cavum septum pellucidum detected by MRI in patients with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1996; 26:431-434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. DeLisi LE, Hoff AL, Kushner M, Degreef G: Increased prevalence of cavum septum pellucidum in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1993; 50:193-199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kwon JS, Shenton ME, Hirayasu Y, Salisbury DF, Fischer IA, Dickey CC, Yurgelun-Todd D, Tohen M, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW: MRI study of cavum septi pellucidi in schizophrenia, affective disorder, and schizotypal personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:509-515Link, Google Scholar

10. Fukuzako T, Fukuzako H, Kodama S, Hashiguchi T, Takigawa M: Cavum septum pellucidum in schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 50:125-128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Nopoulos PC, Giedd JN, Andreasen NC, Rapoport JL: Frequency and severity of enlarged cavum septi pellucidi in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1074-1079Link, Google Scholar

12. Schaefer G, Bodensteiner J, Thompson J: Subtle anomalies of the septum pellucidum and neurodevelopmental deficits. Dev Med Child Neurol 1994; 36:554-559Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Nopoulos P, Krie A, Andreasen NC: Enlarged cavum septi pellucidi in patients with schizophrenia: clinical and cognitive correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 12:344-349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar