Optimal Length of Continuation Therapy in Depression: A Prospective Assessment During Long-Term Fluoxetine Treatment

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine prospectively the optimal length of therapy in a long-term, placebo-controlled continuation study of patients who responded to acute fluoxetine treatment for major depression (defined by DSM-III-R). Method: The study was conducted at five outpatient psychiatric clinics in the United States. Patients who met criteria for remission after 12 or 14 weeks of open-label acute fluoxetine therapy, 20 mg/day (N=395 of 839 patients), were randomly assigned to one of four arms of a double-blind treatment study (50 weeks of placebo, 14 weeks of fluoxetine and then 36 weeks of placebo, 38 weeks of fluoxetine and then 12 weeks of placebo, or 50 weeks of fluoxetine). Relapse rate was the primary outcome measure. Both Kaplan-Meier estimates and observed relapse rates were assessed in three fixed 12-week intervals after double-blind transfers from fluoxetine to placebo at the start of the double-blind period and after 14 and 38 weeks of continued fluoxetine treatment.Results: Relapse rates (Kaplan-Meier estimates) were lower among the patients who continued to take fluoxetine compared with those transferred to placebo in both the first interval, after 24 total weeks of treatment (fluoxetine, 26.4%; placebo, 48.6%), and the second interval, after 38 total weeks of treatment (fluoxetine, 9.0%; placebo, 23.2%). In the third interval, after 62 total weeks of treatment, rates were not significantly different between the groups (fluoxetine, 10.7%; placebo, 16.2%). Conclusions: Patients treated with fluoxetine for 12 weeks whose depressive symptoms remit should continue treatment with fluoxetine for at least an additional 26 weeks to minimize the risk of relapse. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1247-1253

Research on use of antidepressants has largely focused on acute treatment of depression (1, 2), with the goal of decreasing symptoms and achieving a remission (3, 4). During the last few decades, however, the chronic nature of major depression has been demonstrated (1, 2, 5, 6), and attention is increasingly focusing on continuation and maintenance treatments. Continuation therapy strives to prevent relapse(3, 4), a return of symptoms meeting the full criteria for a major depressive episode during an initial period of remission (4). In contrast, maintenance or prophylactic therapy strives to prevent recurrence, an entirely new episode of major depression (4). Because of the difficulty in determining whether a depressive episode has truly ended or whether it is simply suppressed, relapse and recurrence are difficult to distinguish in clinical practice. Data defining the length of untreated episodes of major depression are limited, although several researchers have suggested that an individual episode typically varies from less than 1 month to more than 2 years (5, 6).

In the context of these observations, it has been suggested that antidepressants suppress depressive symptoms before the pathophysiology underlying the disorder resolves (7), and that this creates a “window” during which time patients are vulnerable to a relapse, as defined above, if medication is withdrawn (8). Recommendations for the length of continuation therapy have generally ranged from 4 to 6 months (8-14). The studies that have provided the basis for these recommendations, however, were designed to demonstrate the need for continuation therapy, not its optimal duration. We are unaware of any previous studies that have prospectively examined several different lengths of continuation therapy under controlled conditions.

Although there is evidence that maintenance treatment is of benefit for patients with recurrent depression (15, 16), many patients are unwilling to commit themselves to indefinite therapy with antidepressant medications because of side effects, cost, the wish to become pregnant, and other reasons. For these patients and for patients being treated for an initial episode of depression, the optimal length of continuation therapy remains an important question.

The present study was designed to assess prospectively the optimal length of continuation therapy after successful acute therapy with fluoxetine, 20 mg/day, as a part of a study of long-term fluoxetine treatment of depression. All previous placebo substitution studies reported in the literature have used a single transfer point in comparing medication with placebo. The present study is unique in prospectively planning three transfer points over increasing lengths of time during the double-blind portion of the study.

METHOD

The study subjects were male and female outpatients, 18–65 years of age, who met the DSM-III-R criteria for major depression with a duration of at least 1 month. Patients with type I bipolar disorder were excluded from the study, but depressed patients with type II bipolar disorder could be included if they met other entry criteria. All patients had a modified 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17) score of at least 16. The modified 17-item Hamilton scale was derived from a 28-item Hamilton depression scale that contained three extra items dealing with oversleeping and two dealing with overeating and weight gain which were derived from the Reversed Vegetative Symptoms Scale (18). Neurovegetative status was initially determined on the basis of which set of sleeping and eating item scores was higher, and only the higher set was used to calculate the modified 17-item Hamilton depression scale score. Ifthe two scores were equal, positive neurovegetative status was assigned. After a complete description of the study, all patients gave written informed consent before their participation.

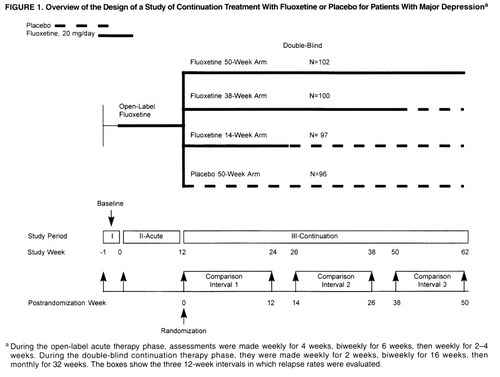

The study was conducted at five outpatient psychiatric clinics in the United States. It consisted of three study phases: a 1-week (5- to 9-day) medication-free baseline phase; a 12- to 14-week open-label acute therapy phase during which all patients received fluoxetine, 20 mg/day; and a 50-week double-blind, long-term therapy phase. At the end of the acute phase, patients whose symptoms had remitted (see below) were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups: 50 weeks of placebo (no continuation therapy), 14 weeks of continuation therapy with fluoxetine followed by placebo, 38 weeks of continuation therapy with fluoxetine followed by placebo, or 50 weeks of continuation therapy with fluoxetine (figure 1). To ensure the comparability of groups with respect to likelihood of relapse, patients were classified as having a high or low probability of relapse. The presence of any of the following defined high probability of relapse: onset of symptoms 24 months or more before the study, diagnosis of the current episode of depression as chronic, poor interepisode recovery as assessed by the investigator, or an interval of less than 24 months between the most recent previous episode and the current episode of depression. Random assignment to each treatment arm was then stratified by high and low probability of relapse.

Remission was defined as no longer meeting the DSM-III-R criteria for major depression and having a Hamilton depression scale total score less than 7 for 3 consecutive weeks, both of which were to be maintained until the end of the acute therapy phase. Patients who did not meet the remission criteria by week 9 could have the acute therapy phase extended for up to 2 weeks if their Hamilton depression score was 10 or less and had decreased 50% or more from baseline.

Patients who met the criteria for major depression (even if all symptoms were classified as mild) for at least 2 weeks at any assessment during the double-blind phase or who had a Hamilton depression score of 14 or more for 3 consecutive weeks were considered to have experienced a relapse. Relapse rates were calculated during the three 12-week periods after each double-blind transfer from fluoxetine to placebo, i.e., after 12, 26, and 50 total weeks of treatment. Some previous studies have evaluated the rate of relapse during the 8 weeks after discontinuation of active therapy (8), but because of the long half-life of fluoxetine and its active metabolite norfluoxetine, we chose a 12-week interval for the present study.

The primary outcome measure was rate of relapse for patients in the fluoxetine and placebo treatment groups during each of the three fixed 12-week intervals.

We used two approaches in the statistical analysis of the relapse rates for each interval. In the first, observed relapse rates were calculated as the number of relapses divided by the total number of patients who either relapsed or completed the time interval. Data stratified by sites and gender within each transfer interval were combined by using the Mantel-Haenszel procedure for pooling information from 2×2 contingency tables. This procedure assumes that differences in rates are homogeneous among different investigators and by gender. Since this assumption was not satisfied in one instance (transfer interval 1, weeks 12–24), an alternative procedure by DerSimonian and Laird (19) was adopted to estimate differences in pooled rates across sites and gender for this interval. This procedure incorporates heterogeneity of treatment effects among clinics and by gender in the estimate and analysis of overall treatment efficacy. Patients who discontinued for any reason other than relapse were excluded from the analysis of differences in observed relapse rates.

Second, a Kaplan-Meier survival data analysis approach was used to estimate relapse rates for patients who continued fluoxetine treatment and those who were transferred to placebo treatment within each double-blind transfer interval. This approach permits estimates of the probability of relapse as a function of time even in the presence of censored observations. Kaplan-Meier estimates for each interval are thus based on data from all patients observed during that interval, whereas observed relapse rates for each interval are derived only from the data of patients who either relapsed or completed the interval without relapsing.

All statistical hypothesis tests (Kaplan-Meier proportion, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, DerSimonian-Laird) of estimated relapse rates are based on large-sample asymptotic normal test statistics.

RESULTS

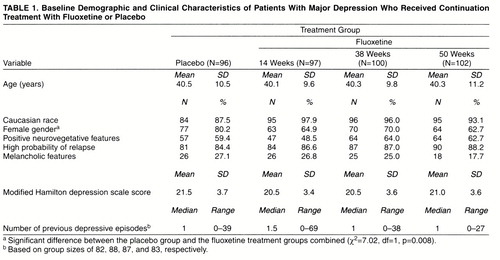

The participants in the study were 577 female and 262 male patients whose mean age was 40 years (SD=11). After 12–14 weeks of acute treatment, 274 female and 121 male patients met the criteria for remission and were randomly assigned to one of the four continuation treatment study arms. An additional 11 patients met the criteria for remission but chose not to continue in the study. Among the patients assigned to continuation treatment, 42 did not meet the remission criteria until late in the acute phase and had their acute treatment period extended by 1–2 weeks; an additional 16 patients entered the continuation phase of the study with a Hamilton depression score of 7 or less at the final acute phase assessment but had not had 3 consecutive weeks of meeting the remission criteria. There were no significant differences among the patients in the four treatment arms in age or race; however, significantly more women were randomly assigned to the placebo (no continuation therapy) arm than to the other three treatment arms (table 1). The mean baseline Hamilton depression score for all patients assigned to continuation therapy was 20.9 (SD=3.6), and the median number of previous depressive episodes was one (range=0–69). The proportions of patients with high probability of relapse were similar in all groups, as were the mean numbers of previous depressive episodes. Overall, 86.6% of the patients randomly assigned to continued fluoxetine treatment or placebo treatment had a high probability of relapse (table 1).

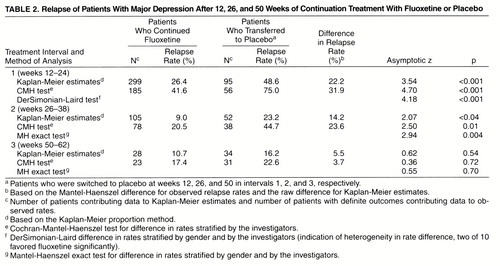

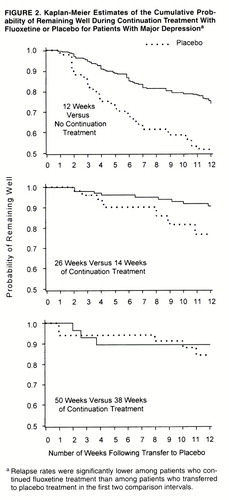

Observed relapse rates and Kaplan-Meier estimates of relapse rates at the end of each interval, along with differences in these rates between patients who continued fluoxetine treatment and those transferred to placebo during each of the three 12-week intervals of the double-blind phase, are summarized in table 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of remaining well (and conversely, of relapse) are presented graphically in figure 2.

Relapse rates (Kaplan-Meier estimates) were significantly lower for the patients who continued fluoxetine treatment than for the patients who transferred to placebo treatment in the first two intervals but not the third (table 2 and figure 2). Similarly, observed relapse rates were significantly lower for the patients who continued fluoxetine treatment than for the patients who transferred to placebo treatment in the first two transfer intervals but were not statistically different in the third interval (table 2).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study, designed to assess prospectively the optimal length of continuation therapy, show significantly lower relapse rates for fluoxetine-treated patients compared with placebo-treated patients for at least 26 weeks after 12 weeks of successful acute treatment (38 weeks of treatment in total).

These findings are consistent with those of earlier studies (10, 13, 20-22) as well as with current guidelines of the Agency for Health Care Policy Research (23), which suggest that patients should receive 4–9 months of continuation therapy after remission of symptoms. Those studies, however, were designed primarily to evaluate the need for further antidepressant medication therapy and did not distinguish between continuation therapy and maintenance/prophylactic therapy. Placebo was substituted for active medication quite soon after remission was achieved, and the period of observation for reappearance of clinically significant depressive symptoms varied from 2 to 8 months. Prien and Kupfer (8) did distinguish between continuation and maintenance therapies, but all patients received a uniform 2 months of continuation therapy with an active agent followed by random assignment to active or placebo maintenance therapy. The optimal duration of continuation therapy—16–20 weeks—was retrospectively determined in that study by examining relapse rates during the first 8 weeks of maintenance therapy and then examining how long patients had been symptom free before relapse. These other studies had relatively small numbers of patients, and all used a single transfer point between active medication and placebo. The current study differed in that it was specifically designed to examine relapse prospectively, after a uniform acute treatment period, during three fixed time intervals to test the accuracy of the accepted treatment guidelines in a large number of patients.

Several factors potentially limit the interpretation of these results. In particular, the distinction between relapse and recurrence is an empirical (time-based) one, and in some instances it may not reflect the underlying pathophysiology of the illness. Therefore, some patients considered to have suffered relapse (return of symptoms from an ongoing episode of depression) may in fact have suffered recurrence (symptoms of a new episode). Similarly, in the subgroup of patients who had had symptoms for long periods, illness might be better thought of as chronic rather than episodic, making the concepts of relapse and recurrence problematic. These issues reflect similar problems in clinical practice and, from the perspective of practice, do not affect the findings of this study with respect to the minimum time necessary for adequate continuation treatment; independent of the conceptual framework, continuation treatment for 26 weeks after 12 weeks of acute fluoxetine treatment was associated with a clear protective effect. However, early return of symptoms in patients at high risk could have reduced the statistical power of the study to detect differences between treatments in the final comparison interval, and the study may have underestimated the benefit of extending treatment for longer periods with respect to relapse prevention. In this regard, patient attrition prior to reaching the comparison intervals could also have been a source of potential bias by unbalancing comparison groups with respect to one or more relevant characteristics. Inspection of the data, however, provides no evidence that such a bias actually occurred. Finally, patients with type II bipolar affective illness were not excluded from the study and could have had different risks with respect to relapse than patients with unipolar illness. However, an analysis of this subgroup of patients (which has been reported elsewhere [24]) suggests that their relapse rates were similar to those of unipolar patients and that inclusion of these patients did not change the outcome of the study.

In the current study, Kaplan-Meier estimated relapse rates in the fluoxetine and placebo groups, respectively, were 26.4% and 48.6% at the end of the first interval, 9.0% and 23.2% at the end of the second interval, and 10.7% and 16.2% at the end of the final interval. Prien and Kupfer (8) reported relapse rates of 50% with placebo and 22% with active treatment within 8 weeks of treatment assignment, while Robinson et al. (25) reported relapse rates of 75% with placebo and 10.5%–16.7% with two different doses of phenelzine within 3 months of treatment assignment. The degree of protection provided by continuation therapy with fluoxetine is similar to that described in previous studies. The observed relapse rates, however, are difficult to compare for several reasons. The current study was designed to be highly sensitive to relapse and used a definition of relapse that set a relatively low threshold and may have included patients who would not have been considered to have relapsed in other studies or in clinical settings. Further, relapse rates were highest in the first comparison interval, a period in which both patients and clinicians were aware that random assignment to treatment had occurred for the first time, and in which there was an increase in the frequency of assessments from biweekly to weekly at the time of assignment. These factors may have made patients and investigators more sensitive to symptoms suggestive of relapse in the first interval, perhaps exaggerating the decrease in relapse rates observed over time. Finally, the patients in this study had many features that may be associated with poorer prognosis over time (high chronicity, multiple episodes, poor interepisode recovery), which may have contributed to relatively high relapse rates. We also note that relapse rates under naturalistic conditions may well be lower than those observed under the controlled conditions of this study, since in clinical practice interventions such as dose adjustments and the addition of other medications are available.

The highest rates of relapse were observed in the first interval after transfer to placebo treatment, where the duration of sustained remission of depressive symptoms was the shortest (as little as 3 weeks for some patients). Differences in Kaplan-Meier estimates of relapse rates and those in observed relapse rates were statistically significant for the first and second transfer intervals. Although significantly more women were assigned to the placebo treatment arm (no continuation therapy) than to the other three treatment arms, reanalysis adjusting for this gender imbalance did not change the outcome. These data are consistent with findings of previous studies, especially the analysis of Prien and Kupfer (8), and because the times of transfers to placebo were randomly assigned to different intervals, they provide prospective, controlled confirmation of the observation that significant protection against relapse is afforded by treatment for at least 26 weeks after resolution of symptoms.

Although there was not a statistically significant difference in relapse between the fluoxetine and placebo treatment groups during the last interval, these data are not definitive. Because of patient attrition over the course of the year, the sizes of the groups in the last interval were relatively small, and the statistical power to detect treatment effects was correspondingly diminished. The loss of statistical power due to loss of subjects is magnified by the decrease in frequency of relapse over time, since with fewer events a larger sample is required to observe any effect that might be present. In addition, many patients had relatively long-standing symptoms at the time of entry into the study. Especially during the later stages of the study, these patients may have come to the “natural” end of their depressive episodes and been at relatively low risk of relapse. As a result, the rates of relapse observed in the last comparison interval may underestimate those which would be observed in a group of patients all of whom presented for treatment near the onset of their illness. For these reasons, the failure to demonstrate a difference between treatments during the last interval is difficult to interpret, and we cannot rule out the possibility that longer treatment does confer increased protection against relapse.

In evaluating these results, it is important for clinicians to keep in mind that this study was designed to address the optimal length of continuation treatment—the amount of additional therapy after symptom resolution of an acute depressive episode that is necessary to prevent the return of clinically significant depressive symptoms related to that episode. In that regard, these data suggest that 26 additional weeks of fluoxetine treatment after 12 weeks of acute therapy is the minimum required duration of treatment. Because of limitations in the final comparison interval, it is possible that protection against relapse would be associated with further treatment. It is also important to keep in mind that prevention of recurrence (as opposed to relapse) likely requires longer periods of treatment, and that studies demonstrating the effectiveness of maintenance antidepressant therapy in preventing new episodes of depression (15, 16) suggest that for many patients, additional benefit is associated with ongoing treatment beyond the period studied here.

The efficacy of fluoxetine for the acute treatment of major depression has been well established. The results of this study demonstrate that treatment with fluoxetine is superior to placebo in sustaining remission of depressive symptoms following acute treatment and that the optimal length of continuation therapy after 12 weeks of acute therapy is at least 26 additional weeks.

Presented in part at the 147th and 150th annual meetings of the American Psychiatric Association, Philadelphia, May 21–26, 1994, and San Diego, May 17–22, 1997, respectively.Received Oct. 31, 1997; revision received March 10, 1998; accepted March 24, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston; the Department of Psychiatry, Rush Medical Center and Presbyterian–St. Luke"s Medical Center, Chicago; and Lilly Research Laboratories, Eli Lilly and Co.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Michelson, Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN 46285. Supported by a grant from Lilly Research Laboratories.

|

|

1. Kupfer DJ: Maintenance treatment in recurrent depression: current and future directions: the first William Sargant lecture. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 161:309–316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Montgomery SA: Long-term treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165(suppl 26):31–36Google Scholar

3. Kupfer DJ, Keller MB: Management of recurrent depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54(suppl 2):29–35Google Scholar

4. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851–855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Angst J, Baastrup P, Grof P, Hippius H, Pöldinger W, Weis P: The course of monopolar depression and bipolar psychoses. Psychiatr Neurol Neurochir 1973; 76:489–500Medline, Google Scholar

6. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Taylor J: Long-term outcome of episodes of major depression: clinical and public health significance. JAMA 1984; 252:788–792Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Post F: Imipramine in depression (letter). BMJ 1959; 2:1252Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Prien RF, Kupfer DJ: Continuation drug therapy for major depressive episodes: how long should it be maintained? Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:18–23Google Scholar

9. Coppen A, Noguera R, Bailey J, Burns BH, Swani MS, Hare EH, Garner R, Maggs R: Prophylactic lithium in affective disorders. Lancet 1971; 2:275–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Prien RF, Klett CJ, Caffey EM: Lithium carbonate and imipramine in prevention of affective episodes: a comparison in recurrent affective illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 29:420–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bjork K: The efficacy of zimelidine in preventing depressive episodes in recurrent major depressive disorders—a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1983; 308:182–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Montgomery SA, Dufour H, Brion S, Gailledreau J, LaQueille X, Ferrey G, Moron P, Parant-Lucena N, Singer L, Danion JM, Beuzen JN, Pierredon MA: The prophylactic efficacy of fluoxetine in unipolar depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1988; 3:69–76Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mindham RH, Howland C, Shepherd M: An evaluation of continuation therapy with tricyclic antidepressants in depressive illness. Psychol Med 1973; 3:5–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders: a consensus statement. J Affect Disord 1989; 17:197–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Frank E, Kupfer D, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093–1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Perel JM, Cornes C, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Five-year outcome for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:769–773Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Thase ME, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Hamer T, Kupfer DJ: Treatment of imipramine-resistant recurrent depression, III: efficacy of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:5–11Medline, Google Scholar

19. DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7:177–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Klerman GL, DiMascio A, Weissman M, Prusoff B, Paykel ES: Treatment of depression by drugs and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131:186–191Link, Google Scholar

21. Coppen A, Ghose K, Montgomery S, Rama Rao VA, Bailey J, Jorgensen A: Continuation therapy with amitriptyline in depression. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:28–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Stein MK, Rickels K, Weise CC: Maintenance therapy with amitriptyline: a controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137:370–371Link, Google Scholar

23. Agency for Health Care Policy Research: Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical Practice Guidelines, vol 5, number 2; AHCPR publication number 93-0550. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1993 Google Scholar

24. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Fawcett J, Quitkin FM, Reimherr FW, Rosenbaum JF, Schweizer E, Beasley CM: Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in bipolar II major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol (in press)Google Scholar

25. Robinson DS, Lerfald SC, Bennett B, Laux D, Devereaux E, Kayser A, Corcella J, Albright D: Continuation and maintenance treatment of major depression with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine: a double-blind placebo-controlled discontinuation study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1991; 27:31–39Medline, Google Scholar