Factual Sources of Psychiatric Patients’ Perceptions of Coercion in the Hospital Admission Process

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine what predicts patients’ perceptions of coercion surrounding admission to a psychiatric hospital.Method: For 171 cases, the authors integrated data from interviews with patients, admitting clinicians, and other individuals involved in the patients’ psychiatric admissions with data from the medical records. Using a structured set of procedures, coders determined whether or not nine coercion-related behaviors occurred around the time of admission. Correlation and regression analyses were used to describe the predictors of patients’ scores on the MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale.Results: The use of legal force, being given orders, threats, and “a show of force” were all strongly correlated with perceived coercion. A least squares regression accounted for 43.3% of the variance in perceived coercion. The evidence also suggested that force is typically only used in conjunction with less coercive pressures.Conclusions: Force and negative symbolic pressures, such as threats and giving orders about admission decisions, induce perceptions of coercion in persons with mental illness. Positive symbolic pressures, such as persuasion, do not induce perceptions of coercion. Such positive pressures should be tried in order to encourage admission before force or negative pressures are used. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1254-1260

Coercive treatment of the mentally ill is a controversial topic. Critics of involuntary commitment have argued that coercion in mental health treatment does more harm than good, causing patients to distrust caregivers, become alienated, avoid treatment, and encourage others to avoid treatment (1, 2). Indeed, these feelings seem incompatible with the collaborative relationship so important to adherence to treatment (3–5). Advocates have asserted that persons with mental illnesses would be more likely to seek treatment if they were routinely involved in decision making about treatment (6-11). This implies that clinical outcomes would also be better if hospitalization decisions were made less coercively.

On the other hand, many experienced mental health professionals believe that the use of coercion is sometimes necessary to ensure that patients receive needed care (12, 13). In this view, coercive treatment is often necessary when the patient is too ill to grasp the need for it. Involuntary treatment does not necessarily lead to the alienation of patients from their caregivers or the mental health system but instead engages the patient in treatment (14). A successful intervention may change the client’s views about the desirability of treatment (15).

Until recently, research on coercion in mental health treatment has been sporadic and uncoordinated. However, the 1990s have seen a substantial number of new empirical studies related to coercion in mental health care (16-23) and an accompanying international interest in the topic (24-26) focused on the MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (27), a method for reliably measuring patients’ perceptions of coercion. Investigators have capitalized on this development and have produced a reasonable picture of the cognitive structure of patients’ perceptions of coercion in the psychiatric admission process. Indeed, most recent research has focused on the correlates of “perceived coercion” (17–19, 21-24).

The structure of patients’ perceptions, however, is only part of the issue. To minimize patients’ experiences of coercion, either for ethical reasons or because coercion may reduce adherence to treatment, we also need to know what events and behaviors change patients’ perceptions of coercion. Unfortunately, patients’ reports alone are of limited help in determining what makes them feel coerced (28). Patients, like everyone else, have limited ability to assess the determinants of their decisions and affective reactions (29).

How can we determine whether behaviors or events that might affect perceived coercion “really” occurred? There appear to be only three ways. First, one might use direct observation. Although observation is a very rich data source, it is tremendously expensive and limited to events that occur in the presence of the observer. For example, one can observe only that part of the hospital admission process which occurs in public places, such as emergency rooms; coercive interactions that occur in the patient’s home before he or she comes to the hospital are lost. A second approach would be to look for “objective traces” of coercive behaviors, such as the presence of a chart note about of the use of handcuffs or a legal commitment order. These measures are usually only grossly descriptive of the admission process (20) and may be difficult to obtain consistently.

The third method is interviewing participants, specifically the patient, clinician, and other people involved in the admission process. To produce more than simply a compilation of reported events, however, a systematic method for “triangulating” these accounts must be developed. We have described such a procedure for generating a “most plausible factual account” of an admission process (28). This procedure involves listening to audiotapes of semistructured interviews about a hospital admission with the patient, the admitting clinician, and a third party who was closely involved with the admission (usually, a family member or friend) as well as reviewing the medical record. Using a rule-governed procedure, coders combine these data into scores indicating the likelihood that particular coercion-related behaviors occurred. Interrater reliability on this coding task has been quite good (28).

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between patients’ perceived coercion and scores on coercion-related behaviors generated by the coding process for the most plausible factual account. The use of multiple data sources and a systematic method for coding whether a behavior or event occurred allows us to understand better what coercion-related behaviors are most influential in producing the feeling of coercion in patients.

METHOD

Between July 1992 and August 1994, we studied 433 cases at two university-based hospitals, one in Pennsylvania (237 cases) and one in Virginia (196 cases). Patients were interviewed within 48 hours after admission. In 87% of the cases (N=378), we were also able to interview the admitting clinician. In addition, we interviewed a “collateral person”—defined as someone who knew a considerable amount about the circumstances of the admission—in 49% (N=212) of the cases. Typically, this was a family member or friend, but for many chronic patients, a mental health professional was the appropriate person to be interviewed. In 45% of the cases in which a collateral person was not interviewed, the admission process was undertaken by the patient alone, and thus the patient could not name such a person. The study and the interview were thoroughly explained to all persons who were interviewed, and written consent was obtained. We also obtained written consent from the patients to contact and interview clinicians and collateral persons.

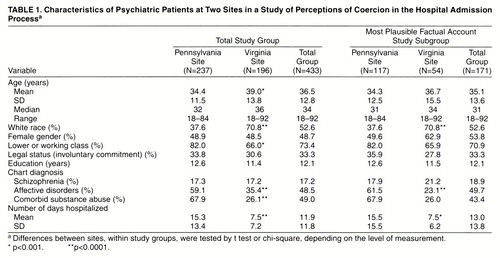

The study group was selected consecutively except when a large number of patients were admitted and could not be interviewed within the time limit or when patients’ involvement with treatment precluded their taking time for the interview. Patients with diagnoses of dementia or more than mild mental retardation were excluded because of difficulties in completing the interview. The Pennsylvania and Virginia interviewers were trained together, including observing each others’ interviews, and periodically reviewed audiotapes of each others’ interviews. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study groups at the two sites.

A subgroup of 171 cases were used in the present study. These were the cases in which the data were sufficient and of high-enough quality to allow for coding the most plausible factual account (28). Although this selection of subjects has the potential of creating a bias, the patients whose cases were coded were not significantly different (at p=0.01) from those whose cases were not coded with respect to age, race, gender, marital status, education, occupation, employment status, legal status, length of stay, diagnosis, whether or not seclusion or restraint was used, or the subject’s perceived coercion score on the MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (27). The cases were, however, drawn disproportionately from the Pennsylvania site (68.4% of the cases), since the Virginia site had difficulties obtaining clinician interviews.

Each person interviewed was administered the MacArthur Admission Experience Interview, a semistructured interview that was modified slightly for the different types of interviewed persons. The interview focused on the person’s perceptions of 1) coercion in the admission decision, 2) any pressures on the patient to be hospitalized, and 3) how the patient was treated by others during the process of coming to the hospital and being admitted.

The initial part of the interview was open-ended. In it, the person being interviewed was encouraged to describe the process of coming into the hospital. The second part of the interview included structured questions with predetermined answer sets.

The Admission Experience Interview yielded a “perceived coercion score.” Gardner et al. (27) reported psychometric analyses of four questions in the Admission Experience Interview that constitute the MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale. These questions focus on influence (“What had more influence on your being admitted: what you wanted or what others wanted?”), control (“How much control did you have?”), choice (“You chose,” or “Someone made you”), and freedom (“How free did you feel to do what you wanted?”). These questions were weighted by means of a principal components analysis to yield a continuous scale of perceived coercion, with higher values indicating more perceived coercion. In the original study, the mean value was 1.75 (SD=2.07).

Using a detailed code book (appendix 1), two coders produced most plausible factual account scores on the following nine coercion-related behaviors or events occurring during the admission process.

| 1. | Persuasion—a verbal effort to get the person to sign into the hospital that relies on reason, the subject’s desire to please the persuader, and other motives that do not involve modifying the subject’s environment. | ||||

| 2. | Inducement—a conditional statement in which the potential patient is offered something positive in exchange for agreeing to admission. | ||||

| 3. | Threats—a conditional statement in which the potential patient is told that the threatener will do something negative if the potential patient does not agree to admission. | ||||

| 4. | Show of force—an act that demonstrates the availability of force if it is needed (such as calling the police or hospital security). | ||||

| 5. | Physical force—an act involving the laying on of hands to accomplish something against the expressed choice of the potential patient. | ||||

| 6. | Legal force—use of the authority of the courts to facilitate the admission; in all but two cases, this meant involuntary commitment. | ||||

| 7. | Request for a dispositional preference—whether anyone asked what the patient wanted to do about admission. | ||||

| 8. | Giving orders—a statement related to the admission in which someone stated that the patient had to do something; this is distinguishable from a threat by the lack of a conditional result. | ||||

| 9. | Deception—lies or deliberate deceit of any sort. | ||||

In general, scores in the most plausible factual account have the closest association with patients’ scores, probably because only the patient is present at all aspects of the admission process. However, the force score in the most plausible factual account is most closely correlated with clinicians’ scores on force. Only the most plausible factual account score for whether the patient was asked about his or her preference correlates strongly with the score of just one participant (the patient). Details have been published elsewhere (28).

RESULTS

Frequencies of Coercion-Related Behaviors

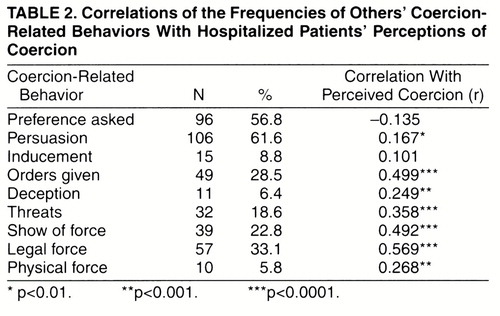

The frequencies of the nine coercion-related behaviors are presented in table 2. Persuasion was the most common method used to try to get patients to come into the hospital. However, 49% (N=83) of the patients experienced at least one of the following: being given orders, threats, a show of force, legal force, or physical force.

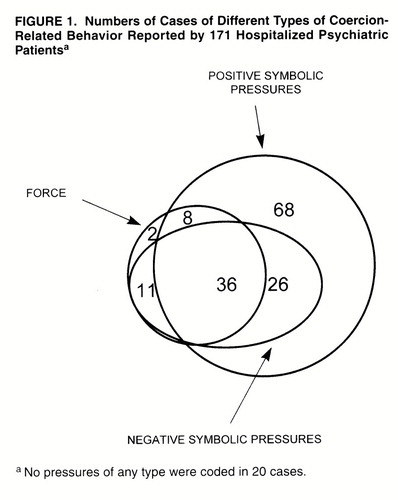

Conceptually, it is possible to group these coercion-related behaviors into three influence types: positive symbolic pressures, negative symbolic pressures, and force. (These categories should not be confused with “positive pressures” [persuasion and inducements] and “negative pressures” [threats and force] as used in some of our previous work [4, 6]). Doing so allows for a more focused examination of relationships. Positive symbolic pressures, including persuasion, inducement, and asking for a preference, use words to encourage individuals to make the “right” choice. Asking for a preference might not seem to be a pressure, but it is typically part of an effort to get the potential patient to “own the problem” and thus respond to it (30); thus, it may be a mild pressure. Negative symbolic pressures include threats, giving orders, deception, and show of force. Despite its verbal similarity to force, show of force is closer to a threat than an imposition of force. For example, bringing a burly security man to sit outside the admitting office door constitutes a threat to use force rather than actual use of force. Finally, legal force and physical force are grouped together because they completely remove from the patient the option to refuse what the other party wants to do.

As shown in figure 1, these types of coercion-related behaviors occurred invarious combinations. Cases with only positive symbolic pressures constituted by far the largest group, about 40% of the cases. No pressures of any type were seen in 12% of the cases, and 21% of the cases had coercion-related behaviors of each type.

These results suggest a model of the structure of the different types of coercion-related behaviors in which a negative symbolic pressure does not occur without a positive symbolic pressure, and force does not occur without a negative symbolic pressure. Such a model can be visualized as a pyramid with force on top, negative symbolic pressures in the middle, and positive symbolic pressures at the base. Such a model suggests that when force occurs, the case will always have a negative symbolic pressure. The data show that this model held in 82.5% (N=57) of the cases. Similarly, the model suggests that when negative symbolic pressure occurs, the case will always have a positive symbolic pressure. The data show this to have been true in 84.9% (N=73) of the cases.

Why does this model not hold all of the time? By analyzing the deviant cases, we found that there were significantly different patterns at the two data collection sites. Thus, in cases in which force was used, all of the Virginia cases involved the use of negative symbolic pressures, but only 76.2% (N=42) of the Pennsylvania cases did (χ2=6.84, df=1, p<0.001). However, in the cases having negative pressures, the Virginia site had positive symbolic pressures in 61.1% (N=18) of the cases, whereas the Pennsylvania site had them in 92.7% (N=55) of the cases (χ2=9.16, df=1, p<0.005). These differences did not reflect more general propensities of the cases at the two sites to involve different types of pressure. There was no difference at all between the two sites in the use of positive symbolic pressures when there was no negative symbolic pressure involved (χ2=0.0002, df=1, p<0.97). The use of negative symbolic pressures was different at the two sites, but at the Virginia site they were actually used less than at the Pennsylvania site when no force was involved (χ2=8.81, df=1, p<0.005).

Relationship of Coercion-Related Behaviors to Perceived Coercion

The primary concern of this study was the relationship of the different types of coercion-related behaviors to patients’ perception of coercion. The correlation of each coercion-related behavior to the perceived coercion score is shown in table 2. Clearly, negative types of coercion-related behavior and force were more related to perceived coercion than were positive types of coercion-related behavior.

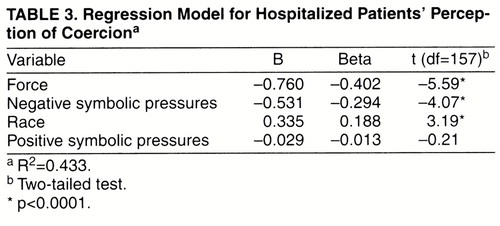

To assess the contributions of each type of pressure to explaining perceived coercion, we did a least squares regression analysis using perceived coercion as the dependent variable and the three types of coercion-related behaviors and demographic variables as the independent variables. To simplify the model, we included only demographic variables that were significantly related to perceived coercion on a bivariate basis. We tested age, race, gender, social class, diagnosis of affective disorder, diagnosis of schizophrenia, comorbid substance abuse, education, length of stay in the hospital, and site. Of these, only race was significantly related to perceived coercion (t=3.06, df=169, p<0.005), with African Americans reporting feeling less coerced than other subjects. Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis. The regression explained 43.3% of the variance. Only force, negative symbolic pressures, and race were significantly related to perceived coercion.

When we tried to duplicate the regression model in the data from each site, the effects of force and negative symbolic pressures were consistent, but the effect of race appeared only at the Pennsylvania site.

DISCUSSION

Whether or not the use of coercion to ensure that mentally ill people receive treatment is justified is a controversy that cannot be entirely resolved by empirical research. However, it is clearly preferable to minimize patients’ perceptions of being coerced, both because it seems inherently undesirable for anyone to feel coerced and because those feelings may undermine cooperation with subsequent treatment. Although much has been written concerning patients’ reports about what makes them feel coerced, little has been written about what behaviors on the part of others (aside from involuntary commitments) actually influence that perception. The approach used here, in which multiple accounts are integrated into one most plausible factual account and related to a validated score for perceived coercion, offers the best picture currently available of what leads patients to feel coerced when being admitted to a hospital.

This study produced four primary findings. First, not surprisingly, force and negative symbolic pressures produce feelings of coercion. As would be expected, legal force (usually commitment) is a very powerful contributor to perceived coercion, but so are threats and giving orders. However, it is important to note that positive symbolic pressures like persuasion, although common, do not result in feelings of coercion.

Second, although a large part of patients’ perceptions of coercion are a result of real pressures, and perceptions of coercion are based on real events, there is much variance unaccounted for in patients’ reports of coercion. We have previously reported that patients’ reports of procedural justice in the process of admission (being listened to, having a chance to participate in the decision, etc.) are strongly correlated with their reports of coercion (23). Our findings in the present study are consistent with these earlier findings, in that the purely behavioral pressures seem to account for only part of the patients’ perceptions of coercion. The unexplained variance of the models tested here could well be related to the interpersonal process of procedural justice.

Third, the interrelationships of the coercion-related behaviors seen in these data raise some intriguing possibilities. It seems that force rarely appears without negative symbolic pressures, and negative symbolic pressures are much more likely to occur in combination with positive symbolic pressures; but positive symbolic pressures often exist without negative symbolic pressures or force. This could indicate some form of sequential temporal process that occurs within the admission process, in which more negative forms of coercion-related behavior are relied upon when more positive efforts fail to achieve a result. Testing whether this sequence of events actually occurs requires a different approach from the one taken in this study (e.g., coding the sequence of exchanges in the admission process) and would certainly be an interesting avenue of research.

Finally, however, it is important that there were substantial differences between sites in these sequences. Most interesting is the fact that at the Pennsylvania site, negative pressures and force were almost never used without first trying positive symbolic pressures, which are not related to perceived coercion. This appears not to have been true at the Virginia site, which suggests that these patterns are not immutable features of the relationship between people with mental illness and their caregivers. They are affected by the community culture regarding psychiatric admissions and thus are modifiable.

When and how others come to rely on force and negative types of coercion-related behavior to get patients to come into the hospital seems a question well worth pursuing. The present results show clearly that these forms of coercion-related behavior have a marked effect on the perception of coercion and that often they may be the end point of a series of exchanges in which the other person has given up on more positive approaches. Reducing coercion in mental health care rests, in part, on answering how the dynamics of these processes work.

Appendix 1. Issues in Coding for the Most Plausible Factual Account

These coding issues have been described in Lidz et al. (28).

The coding of most plausible factual account for this study presented three serious problems that had to be resolved in order to achieve a reliable coding system:

| 1. | Whom should one believe when there are conflicting, or partially conflicting, accounts of an event? | ||||

| 2. | What are the temporal boundaries of the incident being coded? If an event happened 2 weeks before the admission, should it be included in the data being coded? | ||||

| 3. | What role should the coder’s understanding of how things typically happen in such situations play in coding decisions? | ||||

The way in which these questions were answered was central to the structure of the coding system and essential in establishing adequate reliability.

Whom to Believe

Conflicting accounts of the situation that led to hospitalization were routine. However, outright disagreements were rare. More often, conflicting accounts involved differences in what was known or in interpreting people’s motives. Conflicting evidence was resolved with use of the following four hierarchically arranged rules.

| 1. | Always believe an individual’s own account of his or her motives rather than someone else’s account. Questioning of this account must be based on inconsistent objective data, not on someone else’s account of motives for agreed-upon acts. | ||||

| 2. | Believe an eyewitness account before a second-hand report. | ||||

| 3. | Accept the fuller account of an incident rather than the sparser one. | ||||

| 4. | If the preceding rules do not yield a choice of account, believe multiple sources before a single source. | ||||

These four rules allowed us to resolve all conflicting account problems. We added an additional rule to aid our reliability: codes 1 and 5 (certainty) were never used if there were conflicting accounts.

Temporal Boundaries of the Incident

A much less obvious source of disagreement between coders concerned the boundaries of an incident to be coded. For example, if the patient reported that his mother had threatened to commit him if he used crack again, does that count as a threat when he is admitted 2 weeks later? This was a surprisingly frequent and difficult-to-resolve source of disagreement. We used the following rules, which allowed a reliable coding process.

| 1. | All attempts at influence must have occurred since the last hospitalization incident. It seemed reasonable to assume that coercion-related behaviors that occurred before a previous hospitalization were related to that hospitalization, not the present one. | ||||

| 2. | Attempts at influence must have occurred within the last month unless the patient’s own account of his or her motives clearly related the attempt to the present hospitalization. This rule did not influence a large number of codes, except in ongoing disputes about whether the patient should be admitted. In these cases a relative or friend often tried a variety of different techniques to get the patient to go to the hospital, and sometimes one of these happened only in the early stages of the dispute. Thus, for example, a patient’s mother offered to pay for an apartment after he was discharged. When that failed to persuade him, she tried other means and only succeeded in gaining his admission more than a month after the offer. Nonetheless, the patient considered the offer still relevant, and it was a substantial motivator in his final acquiescence. | ||||

| 3. | Attempts at influence must have occurred before the patient was admitted to the hospital. A posthospitalization act, such as trying to persuade the patient that admission was really the right decision, does not count. This rule simply reaffirmed that we were concerned with coercion around the time of admission, not subsequent decisions. | ||||

Who Was “Involved” in the Incident?

One of the most difficult problems in achieving reliability was whom to code as involved. During an interview many persons are mentioned as having been present at, or cooperating with, a decision but had no apparent impact on the decision. We used the following rules.

| 1. | A person should be included only if he or she had something to do with the decision to come into the hospital. For instance, a security guard who was present and did not come there specifically for that patient was not included. | ||||

| 2. | In a specific section of the interview, the interviewed persons were asked to name everyone involved. This established a presumption of who should be included. However, the coder was free to override the presumption in accordance with other rules. | ||||

| 3. | It was not necessary for persons to perform a relevant act themselves. The encouragement or support of another person’s doing so was sufficient. Being informed of the imposition of a particular type of influence (e.g., a commitment) and going along with its implementation was sufficient for that individual to be coded. | ||||

How to Categorize Persons?

All categories of persons required special rules to define their boundaries. Did “sibling” include half-siblings, step-siblings, foster-siblings? The most difficult part of this decision occurred when persons played two roles. Police officers sometimes turned out to be friends, one lover was the patient’s former therapist, etc. If the role had changed, we coded the person’s most recent role. If two roles existed simultaneously, we coded the role that the patient used as the primary descriptor.

Coder’s Background Knowledge

It was sometimes easy to make assumptions about what happened, especially about the actions of admissions staff members when the coders knew the routine procedures used in admission. However, we enforced a strict rule that coding should be based only on the data, not on what we knew “must have happened.”

Received May 23, 1996; revisions received July 21, 1997, and Jan. 13, 1998; accepted Feb. 9, 1998. From the Center for Research on Mental Health Services, University of Massachusetts Medical School; the Law and Psychiatry Program, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, Pa.; and the School of Law, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lidz, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, MA 01655. Supported in part by funds from the Research Network on Mental Health and the Law of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

|

|

|

1. Campbell J, Schraiber R: In Pursuit of Wellness: The Well-Being Project, vol 6. Sacramento, California Department of Mental Health, 1989Google Scholar

2. Morse SA: Preference for liberty: the case against involuntary commitment of the mentally disordered. California Law Rev 1982; 70:54–106Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Siegel LR: Alliance not compliance: a philosophy of outpatient care: compliance strategies to optimize antidepressant treatment outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56(suppl 1):11–17Google Scholar

4. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L: The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:553–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Meichenbaum D, Turk DC: Facilitating Treatment Adherence: A Practitioner’s Handbook. New York, Plenum, 1987Google Scholar

6. Blanch A: Proceedings of Roundtable Discussion on the Use of Involuntary Interventions: Multiple Perspectives. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Community Support Program, 1992Google Scholar

7. Blanch A, Parrish J: Report on Round Table on Alternatives to Involuntary Treatment. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Community Support Program, 1990Google Scholar

8. Rapp C, Shera W, Kisthardt W: Research strategies for consumer empowerment of people with severe mental illness. Social Work 1993; 38:727–735Medline, Google Scholar

9. Parrish J: Involuntary use of interventions: pros and cons. Innovations and Research 1993; 2:15–21Google Scholar

10. Sullivan WP: Reclaiming the community: strengths, perspective and deinstitutionalization. Social Work 1992; 37:204–209Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tempkin T: Summary Notes on Focus Group Meeting on Client Outcomes. Fort Lauderdale, Fla, Consumer/Survivor Mental Health Research and Policy Work Group, 1992Google Scholar

12. Appelbaum PS: Tarasoff and the clinician: problems in fulfilling the duty to protect. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:425–429Link, Google Scholar

13. Geller JL: Rx: a tincture of coercion in outpatient treatment? Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:1068–1069Google Scholar

14. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry Committee on Government Policy: Forced Into Treatment: The Role of Coercion in Clinical Practice: Report 137. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

15. Stone AA: Mental Health and the Law: A System in Transition. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1975Google Scholar

16. Bennett NS, Lidz CW, Monahan J, Mulvey EP, Hoge SK, Roth LH, Gardner WP: Inclusion, motivation and good faith: the morality of coercion in mental hospital admission. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 1993; 11:295–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Cascardi M, Poythress NG: Correlates of perceived coercion during psychiatric hospital admission. Int J Law Psychiatry 1997; 20:445–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Cascardi M, Poythress NG, Ritterband L: Stability of patients’ perceptions of their admission experience. J Clin Psychol 1997; 53:833–840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson J, Wagner HR: Patient perceptions of coercion in mental hospital admissions. Int J Law Psychiatry 1997; 20:227–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hoge SK, Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Roth LH, Bennett NS, Siminoff LA, Arnold RM, Monahan J: Patient, family, and staff perceptions of coercion in mental hospital admission: an exploratory study. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 1993; 11:281–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hoge SK, Lidz CW, Eisenberg M, Gardner W, Monahan J, Mulvey EP, Roth LH, Bennett N: Coercion in the admission of voluntary and involuntary psychiatric patients. Int J Law Psychiatry 1997; 20:1–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Lidz CW, Hoge SK, Gardner W, Bennett NS, Monahan J, Mulvey EP, Roth LH: Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission: pressures and process. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1034–1039Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Nicholson RA, Eksenstam C, Norwood S: Coercion and the outcome of psychiatric hospitalization. Int J Law Psychiatry 1996; 19:201–217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Kaltiala-Heino R, Laippala P, Salokangas R: Impact of coercion on treatment outcome. Int J Law Psychiatry 1997; 20:311–322Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kjellin L: Coercion in Psychiatric Care: Formal and Informal—Justification and Ethical Conflicts. Uppsala, Sweden, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 1996Google Scholar

26. Seigel K, Wallsten T, Torsteinsdottir G, Lindström E: Perceptions of coercion: a pilot study using the Swedish version of the Admission Experience Scale. Nord J Psychiatry 1997; 51:49–54Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Gardner W, Hoge SK, Bennett N, Roth LH, Lidz CW, Monahan J, Mulvey EP: Two scales for measuring coercion during mental hospital admission. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 1993; 11:307–322Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Hoge SK, Kirsch B, Monahan J, Bennett N, Eisenberg M, Gardner W, Roth LH: The validity of mental patient’s reports of coercion-related behaviors in the hospital admission process. Law and Human Behavior 1997; 21:361–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Nisbett R, Ross L: Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1980Google Scholar

30. Lidz CW: Towards a deep structural analysis of moral action, in Structural Sociology. Edited by Rossi I. New York, Columbia University Press, 1982, pp 229–258Google Scholar