Sex Differences in the Striatal Dopamine D2 Receptor Binding Characteristics in Vivo

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated whether striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in vivo are similar in men and women and whether there are sex-related differences in the decline in D2 receptor density due to aging. METHOD: Striatal D2 receptor density (Bmax), affinity (Kd), and binding potential (Bmax/Kd) were measured with positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride in 54 healthy subjects (33 men and 21 women). RESULTS: Women had generally lower D2 receptor affinity than men, and this difference was statistically significant in the left striatum. Bmax and Bmax/Kd tended to decline with age twice as fast in men as in women, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. CONCLUSIONS: These results confirm the age-related reduction of D2 receptor density and binding potential in both sexes in vivo. The lower D2 receptor affinity suggests an increased endogenous striatal dopamine concentration in women. This may have implications for the differential vulnerability of men and women to psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia and alcohol and substance dependence.

Neuroanatomy and neuroimaging studies have revealed gender differences in the volume and morphology of certain brain structures (1–5), cerebral blood flow (6), and glucose metabolism (7–9). Sex differences in behavior and in cognitive and motor abilities have been extensively documented in neuropsychological studies. A consistent finding is that men perform better than women in spatial and motor tasks, whereas women have greater verbal fluency and less functional hemispheric asymmetry than men (10).

Several psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, mood disorders, and alcohol abuse, are thought to be linked to monoaminergic transmission and exhibit gender differences (11–13). However, little is known about the basis of gender differences in monoaminergic transmission in humans. Serotonergic mechanisms have been explored previously by positron emission tomography (PET); and higher 5-HT2 receptor binding capacity was found in men than in women in several brain regions (14). No consistent gender differences have been reported in dopaminergic transmission in humans. In a postmortem study, dopamine and homo~vanillic acid (HVA) concentrations were not found to differ between men and women in several regions in the brain (15). On the other hand, in other studies, women had lower dopamine and higher 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid levels and a higher ratio between this acid and dopamine in postmortem putamen (16) and higher plasma HVA levels (17) than men. In addition, higher HVA concentrations in lumbar CSF were found in women who were postmenopausal or had undergone hysterectomies or ovariectomies than were found in men (18).

While the effect of age on D2 receptor binding characteristics is relatively well established, the data on gender differences in D2 receptor characteristics in vivo are inconsistent. Faster age-related decline in D2 receptors in men (19) and in women (20), as well as no change between the sexes (21), has been reported. In addition, in a postmortem study, striatal D2 receptor density was reported to decline faster in schizophrenic men than in women (22).

The use of PET has made it possible to study the dopaminergic system in the living human brain. The aim of this study was to assess the effect of gender on the D2 receptor binding characteristics and to clarify the effect of age on the decline in D2 receptor characteristics in vivo in healthy men and women through use of PET and [11C]raclopride.

METHOD

The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Turku University and University Hospital. A total of 54 healthy Finnish volunteers (33 men and 21 women), ages 19 to 82 years (mean=40.2, SD=16.7), who gave informed consent, were studied. Of the men, 28 were classified as right-handed, three as left-handed, and two as ambidextrous. All women were right-handed. Women were asked about their menopausal status. The subjects were free of major psychiatric and neurologic disorders. None was a regular smoker, and all had normal computerized tomography or 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain. After a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

The preparation of [11C]raclopride and the quantification of the striatal D2 receptor Bmax and Kd, by using the equilibrium approach, were performed as described previously (23, 24). The Bmax/Kd ratio was calculated as previously described (24).

The statistical analyses were performed with the Systat software package (Systat for Windows, version 5.02, Systat Inc., Evanston, Ill.). Pearson correlation coefficients with probabilities were analyzed for age and receptor binding characteristics. Interactions between age and binding characteristics (homogeneity of regression slopes) for men and women were tested by using analysis of covariance. Homogeneity of group variances was assessed by using Levene's test. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t test were used in the analysis for differences in Bmax, Bmax/Kd, and log-transformed values of Kd between men and women. Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons were not applied, since some of the binding characteristics, i.e., Bmax and Bmax/Kd, show correlations with each other. The level of statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

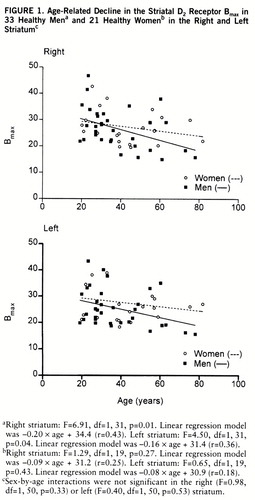

Bmax and Bmax/Kd, but not Kd, showed a significant decline with age, and the decline was similar in the left and right striatum. The decreases in Bmax values in the right and left striatum were 5.0% and 4.0% per decade of life, and the decreases in Bmax/Kd values were 5.3% and 5.9%, respectively. The Pearson correlation coefficient between Bmax and age was –0.35 (F=7.2, df=1,52, p=0.01; estimated regression model=–0.15×age + 32.80) in the right striatum and –0.25 (F=3.51, df=1,52, p=0.07; estimated regression model=–0.11×age + 30.64) in the left striatum. Similarly, the Pearson correlation coefficient between Bmax/Kd and age was –0.49 (F=16.73, df=1,52, p<0.001; estimated regression model=–0.016×age + 3.33) in the right striatum and –0.54 (F=21.54, df=1,52, p<0.001; estimated regression model=–0.018×age + 3.40) in the left striatum.

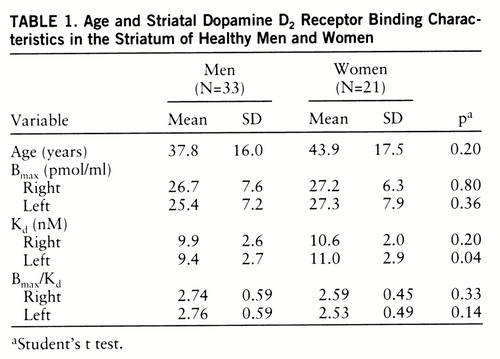

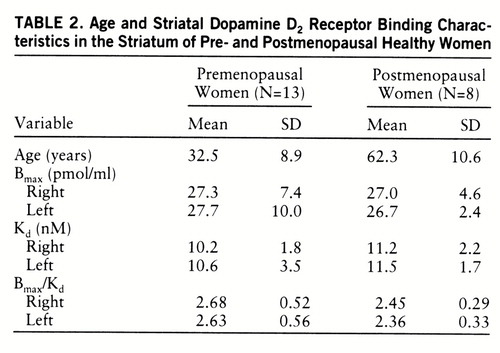

The sex difference in the decline in Bmax and Bmax/Kd due to aging was not statistically significant, but there was a trend for these measures to decrease faster in men than in women (figures 1 and 2). While the Bmax values decreased 6.7% in the right and 5.7% in the left striatum and Bmax/Kd declined 6.5% in the right and 7.0% in the left striatum per decade in men, the corresponding values for women were 3.1% and 3.0%, respectively, for Bmax and 3.5% and 4.2% for Bmax/Kd.

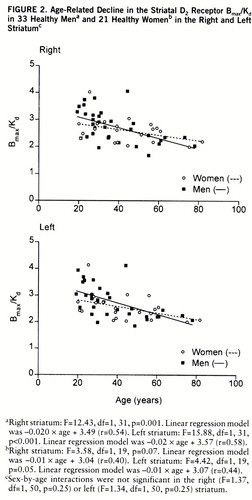

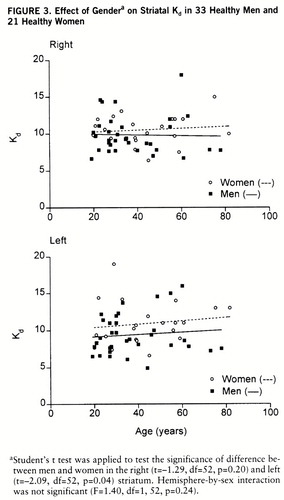

Data on the 33 men and 21 women are presented in table 1. The Bmax and Bmax/Kd values did not significantly differ between sexes. However, the D2 receptor affinity (Kd) was lower in women than in men (figure 3). The gender difference in Kd values was significant in the left striatum (14.5%) (p=0.04) but not in the right striatum (6.7%) (t=–1.29, df=52, p=0.20). Postmenopausal women appeared to have higher Kd values than premenopausal women, but the difference was not statistically significant (table 2). The Kd values in the left striatum were significantly higher in postmenopausal women than in men (18.3%) (t=–2.20, df=39, p=0.03); however, the difference between the two groups in the right striatum was not statistically significant (t=–1.46, df=39, p=0.15). The Kd values of premenopausal women did not differ from those of men. Repeated measures AN~OVA did not reveal different left-right asymmetries in men and women. Left-handed men (N=3) tended to have higher left striatal D2 receptor affinity than right-handed subjects. However, because of the low number of left-handed subjects, no further analysis was attempted.

Variability of the D2 receptor binding characteristics was, in general, higher among premenopausal than postmenopausal women (table 2). Levene's test for the homogeneity of the variances in the D2 receptor binding characteristics between the two groups showed, however, that the variances in the D2 receptor characteristics were not statistically significant (p values between 0.13 and 0.75) except for the left-side Bmax values (F=9.72, df=1,19, p=0.006).

DISCUSSION

Age and D2 Receptor Binding Characteristics

The results of this study confirm the significant decline in D2 receptor Bmax and Bmax/Kd values as a function of age in human striatum. The effect of aging on the decline in striatal D2 receptor density, but not affinity, has been firmly documented in humans in postmortem studies of brains (25–27) and in vivo studies through use of PET (19, 20, 28–31). Similar age-related decreases in the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase (32), levels of dopamine concentration (15, 32, 33), and dopamine uptake (34, 35) have been described, whereas changes in dopa de~carboxylase activity have been inconsistent. Some studies have suggested that dopa decarboxylase activity remains unaltered with age (36–38), and others have suggested that it decreases slightly (39).

It has been suggested that the age-related decline in D2 receptor binding in vivo is different in men and women (19, 20). In a recent in vivo study, covering a relatively narrow age range (20–38 years), neither the D2 receptor characteristics nor the influence of age was found to be different in men and women (21). In the present study the large age range of subjects, from 19 to 82 years, revealed an age-related decline in D2 receptor density and binding potential but not in affinity in vivo. Bmax and Bmax/Kd tended to decline with age twice as fast in men as in women on average, and a significant age-related decline was found only among men. However, the gender difference in age-related decline in density and binding potential did not reach statistical significance.

Gender and D2 Receptor Binding Characteristics

Striatal [11C]raclopride binding has been shown to be sensitive to endogenous dopamine fluctuations in several studies in vivo (40–42). This property has been used to assess changes in endogenous dopamine concentration after pharmacological interventions in human brain in vivo (43, 44). In the present study, the lower affinity of [11C]raclopride in women than in men suggests a gender difference in basal endogenous dopamine concentration in the left striatum. This conclusion is based on a reversible ligand-receptor interaction with competition by endogenous dopamine. This results theoretically in elevated Kd and unchanged Bmax values. It has also been suggested that dopamine noncompetitively inhibits [3H]raclopride binding to D2 receptors in vitro, thus decreasing Bmax, while Kd remains unchanged (45). Ross and Jackson (46) observed in their ex vivo study in mice that the reduction of synaptic dopamine concentration with reserpine and γ-butyrolactone reduced Kd values of [3H]raclopride to D2 receptors because of the competition between dopamine and raclopride. However, the 50% increase in Bmax values after dopamine depletion by reserpine suggested that a pool of D2 receptor sites was not available for raclopride to bind when occupied by dopamine. Recent PET studies in monkeys measured with [11C]raclopride and the equilibrium method showed that the reduction of dopamine concentration in brain by reserpine resulted in higher affinity but no change in D2 receptor Bmax (47). This corresponds to competitive inhibition between [11C]raclopride and dopamine and supports the interpretation of elevated striatal dopamine concentration in women.

Protein structure may affect the affinity of the ligand for the receptor. Our subjects have been studied for structural mutations in the coding region of the D2 receptor gene (48). The only subject, a 20-year-old man, possessing protein sequence variation in Ser311→Cys showed normal affinity as well as age-corrected Bmax and Bmax/Kd characteristics in vivo compared to the mean values of all subjects, indicating that structural variation in the coding region did not cause the gender difference in the present Kd values.

The sex-related change in endogenous dopamine concentration may be due to hormonal effects on dopaminergic functioning in the striatum. Gonadal steroid hormones are known to modulate dopaminergic transmission in the rat. Biosynthesis (49), concentration (50, 51), degradation (52), uptake (53, 54), and receptor density (55) of dopamine have been shown to fluctuate during the estrous cycle in the rat. Thus far, such differences in humans have not been confirmed. In a PET study, the binding rate constant (k3) of [11C]N-methylspiperone to D2 receptors was reported to fluctuate during the menstrual cycle in women (20). In the current study detailed data on menstrual cycling were not available for all women; however, the effect of menopausal status was analyzed by separately comparing the binding parameters of premenopausal and postmenopausal women to those of all men. The variability in Bmax and Bmax/Kd values was, in general, larger among premenopausal than postmenopausal women, probably because of fluctuation in gonadal steroid hormones during the menstrual cycle; however, this remains to be proven.

The role of gender has become an extensively studied variable in schizophrenia research in the last decade. Numerous studies have noted differences in the age at onset, treatment response, course of illness, and outcome between men and women (11, 56, 57). The present results may bear relevance to a gender difference in schizophrenia. The prognosis of schizophrenic women is regarded as better than that of men, and female patients maintain a higher level of social functioning. Similarly, it has been indicated that men are more likely than women to be affected by negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Because positive (psychotic) symptoms of schizophrenia may derive from overactivity of the dopaminergic system, the current antidopaminergic antipsychotic drug treatment may be better targeted for women and therefore improve the prognosis.

Schizophrenic symptoms appear to correlate with low levels of estrogen across menstrual cycle (58, 59). These observations suggest that estrogen protects against the development of schizophrenia in female subjects (11, 60, 61). Biochemical and behavioral studies in animals have demonstrated that estrogen modulates dopaminergic transmission in striatum; however, both activating and inhibiting effects have been documented. In women, the main effect of estrogen is thought to be antidopaminergic, but the mechanism underlying this interaction is poorly understood. Our data on the lower affinity of [11C]raclopride in women than in men suggest a gender-related difference in synaptic dopamine concentration in the left striatum. The increased dopamine concentration in vivo, especially in postmenopausal women, supports the view that loss of estrogen has a facilitative effect on dopaminergic transmission. According to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia/psychosis, this may have implications for increased vulnerability for psychotic disorders in elderly women, since women are at higher risk than men, e.g., to develop late-onset schizophrenia (62, 63).

The difference in the dopamine D2 system may also affect vulnerability to alcoholism. Alcoholic men have been reported to have a low striatal D2 receptor density (24, 64). It can be speculated that higher dopamine tone in women may play a role in lower vulnerability to alcohol dependence in women. Our results are consistent with the fact that the male to female ratio for alcohol-related disorders is about 2 to 1 or even 3 to 1.

Finally, the gender difference in D2 receptor affinity should be regarded as a preliminary finding, since the difference did not remain significant when a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied. Further studies, including also detailed endocrinological data, are required to delineate the basis of variation in endogenous dopamine concentration between men and women. This may shed light on biological liability factors in psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia and alcohol and substance dependence.

|

|

Received June 16, 1997; revision received Dec. 1, 1997; accepted Dec. 5, 1997. From the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Turku; Departments of Neurology and Psychiatry, Turku University Central Hospital; and Turku PET Center, Turku, Finland. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hietala, Department of Psychiatry, Turku University Central Hospital/721, 20520 Turku, Finland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Alcohol Research Foundation, Finnish Academy, the Yrj<148> Jahnsson Foundation, the Turku Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (Dr. Pohjalainen), and the P<132>ivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation (Dr. Rinne). The authors thank the staff of Turku PET Center for assistance and Hans Helenius for statistical advice.

FIGURE 1. Age-Related Decline in the Striatal D2 Receptor Bmax in 33 Healthy Mena and 21 Healthy Womenb in the Right and Left Striatumc

aRight striatum: F=6.91, df=1,31, p=0.01. Linear regression model was –0.20×age + 34.4 (r=0.43). Left striatum: F=4.50, df=1,31, p=0.04. Linear regression model was –0.16×age + 31.4 (r=0.36).

bRight striatum: F=1.29, df=1,19, p=0.27. Linear regression model was –0.09×age + 31.2 (r=0.25). Left striatum: F=0.65, df=1,19, p=0.43. Linear regression model was –0.08×age + 30.9 (r=0.18).

cSex-by-age interactions were not significant in the right (F=0.98, df=1,50, p=0.33) or left (F=0.40, df=1,50, p=0.53) striatum.

FIGURE 2. Age-Related Decline in the Striatal D2 Receptor Bmax/Kd in 33 Healthy Mena and 21 Healthy Womenb in the Right and Left Striatumc

aRight striatum: F=12.43, df=1,31, p=0.001. Linear regression model was –0.020×age + 3.49 (r=0.54). Left striatum: F=15.88, df=1,31, p<0.001. Linear regression model was –0.02×age + 3.57 (r=0.58).

bRight striatum: F=3.58, df=1,19, p=0.07. Linear regression model was –0.01×age + 3.04 (r=0.40). Left striatum: F=4.42, df=1,19, p=0.05. Linear regression model was –0.01×age + 3.07 (r=0.44).

cSex-by-age interactions were not significant in the right (F=1.37, df=1,50, p=0.25) or left (F=1.34, df=1,50, p=0.25) striatum.

FIGURE 3. Effect of Gendera on Striatal Kd in 33 Healthy Men and 21 Healthy Women

aStudent's t test was applied to test the significance of difference between men and women in the right (t=–1.29, df=52, p=0.20) and left (t=–2.09, df=52, p=0.04) striatum. Hemisphere-by-sex interaction was not significant (F=1.40, df=1,52, p=0.24).

1 De Lacoste-Utamsing D, Holloway RL: Sexual dimorphism in the human corpus callosum. Science 1982; 216:1431–1432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Swaab DF, Fliers E: A sexually dimorphic nucleus in the human brain. Science 1985; 228:1112–1115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Allen LS, Gorski RA: Sexual dimorphism of the anterior commissure and massa intermedia of the human brain. J Comp Neurol 1991; 312:97–104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Allen LS, Gorski RA: Sex difference in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the human brain. J Comp Neurol 1990; 302:697–706Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Witelson SF, Kigar DL: Sylvian fissure morphology and asymmetry in men and women: bilateral differences in relation to handedness in men. J Comp Neurol 1992; 323:326–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Gur RC, Gur RE, Orbist WD, Hungerbuhler JP, Younkin D, Rosen AD, Skolnick BE, Reivich M: Sex and handedness differences in cerebral blood flow during rest and cognitive activity. Science 1982; 217:659–661Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Andreason PJ, Zametkin AJ, Guo AC, Baldwin P, Cohen RM: Gender-related differences in regional cerebral glucose metabolism in normal volunteers. Psychiatry Res 1994; 51:175–183Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Hitzemann R, Pappas N, Pascani K, Wong C: Gender differences in cerebellar metabolism: test-retest reproducibility. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:119–121Link, Google Scholar

9 Gur RC, Mozley LH, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, Karp JS, Alavi A, Arnold SE, Gur RE: Sex differences in regional cerebral glucose metabolism during a resting state. Science 1995; 267:528–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Bakan P, Putnam W: Right-left discrimination and brain lateralization: sex differences. Arch Neurol 1974; 30:334–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Seeman MV: Gender differences in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1982; 27:107–112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Hirschfeld RMA: Psychosocial predictors of outcome in depression, in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven Press, 1994, pp 1113–1121Google Scholar

13 Brady KT, Grice DE, Dustan L, Randall C: Gender differences in substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1707–1711Link, Google Scholar

14 Biver F, Lotstra F, Monclus M, Wikler D, Damhaut P, Mendlewicz J, Goldman S: Sex difference in 5-HT2 receptor in the living human brain. Neurosci Lett 1996; 204:25–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Adolfsson R, Gottfries CG, Roos BE, Winblad B: Post-mortem distribution of dopamine and homovanillic acid in human brain, variations related to age, and a review of the literature. J Neural Transm 1979; 45:81–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Konradi C, Kornhuber J, Sofic E, Heckers S, Riederer P, Beckmann H: Variations of monoamines and their metabolites in the human brain putamen. Brain Res 1992; 579:285–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Sumiyoshi T, Hasegawa M, Jayathilake K, Meltzer HY: Sex differences in plasma homovanillic acid levels in schizophrenia and normal controls: relation to neuroleptic resistance. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:560–566Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Di Paolo T, Bédard F, Bédard PJ: Influence of gonadal steroids on human and monkey cerebrospinal fluid homovanillic acid concentrations. Clin Neuropharmacol 1989; 12:60–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Wong DF, Wagner HNJ, Dannals RF, Links JM, Frost JJ, Ravert HT, Wilson AA, Rosenbaum AE, Gjedde A, Douglass KH, Pe~tronis JD, Folstein MF, Toung JKT, Burns HD, Kuhar MJ: Effects of age on dopamine and serotonin receptors measured by positron emission tomography in the living human brain. Science 1984; 226:1393–1396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Wong DF, Broussolle EP, Wand G, Villemagne V, Dannals RF, Links JM, Zacur HA, Harris J, Naidu S, Braestrup C, Wagner HN Jr, Gjedde A: In vivo measurement of dopamine receptors in human brain by positron emission tomography: age and sex differences. Ann NY Acad Sci 1988; 515:203–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Farde L, Hall H, Pauli S, Halldin C: Variability in D2 dopamine receptor density and affinity: a PET study with [11C]raclopride in man. Synapse 1995; 20:200–208Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Seeman P: Dopamine receptors: clinical correlates, in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven Press, 1995, pp 295–302Google Scholar

23 Hietala J, SyvÄlahti E, Vuorio K, Någren K, Lehikoinen P, Ruotsalainen U, RÄkkölÄinen V, Lehtinen V, Wegelius U: Striatal D2 dopamine receptor characteristics in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients studied with positron emission tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:116–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Hietala J, West C, SyvÄlahti E, Någren K, Lehikoinen P, Sonninen P, Ruotsalainen U: Striatal D2 dopamine receptor binding characteristics in vivo in patients with alcohol dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994; 116:285–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Severson JA, Marcusson J, Winblad B, Finch CE: Age-correlated loss of dopaminergic binding sites in human basal ganglia. J Neurochem 1982; 39:1623–1631Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Seeman P, Bzowej NH, Guan HC, Bergeron C, Becker LE, Reynolds GP, Bird ED, Riederer P, Jellinger K, Watanabe S, Tourtellote WW: Human brain dopamine receptors in children and aging adults. Synapse 1987; 1:399–404Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Rinne JO, Lönnberg P, MarjamÄki P: Age-dependent decline in human brain dopamine D1 and D2 receptors. Brain Res 1990; 508:349–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Rinne JO, Hietala J, Ruotsalainen U, Sako E, Laihinen A, Någren K, Lehikoinen P, Oikonen V, SyvÄlahti E: Decrease in human striatal dopamine D2 receptor density with age: a PET study with [11C]raclopride. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1993; 13:310–314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Antonini A, Leenders KL: Dopamine D2 receptors in normal human brain: effect of age measured by positron emission tomography (PET) and [11C]raclopride. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993; 695:81–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Wang G-J, Volkow ND, Logan J, Fowler JS, Schlyer D, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann RJ, Gur RC, Wolf AP: Evaluation of age-related changes in serotonin 5-HT2 and dopamine D2 receptor availability in healthy human subjects. Life Sci 1995; 23:PL249–PL253Google Scholar

31 Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, MacGregor RR, Schlyer DJ, Hitzemann R, Wolf AP: Measuring age-related changes in dopamine D2 receptors with [11C]raclopride and [18F]N-methylspiroperidol. Psychiatry Res 1996; 67:11–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 McGeer PL, McGeer EG, Suzuki JS: Aging and extrapyramidal function. Arch Neurol 1977; 34:33–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Carlsson A, Winblad B: Influence of age and time interval between death and autopsy on dopamine and 3-methoxytyramine levels in human basal ganglia. J Neural Transm 1976; 38:271–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J, Logan J, Schlyer D, MacGregor R, Hitzemann R, Wolf AP: Decreased dopamine transporters with age in healthy human subjects. Ann Neurol 1994; 36:237–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Van Dyck CH, Seibyl JP, Malison RT, Laruelle M, Wallace E, Zoghbi SS, Zea-Ponce Y, Baldwin RM, Charney DS, Hoffer PB, Innis RB: Age-related decline in striatal dopamine transporter binding with [123I]β-CIT SPECT. J Nucl Med 1995; 36:1175–1181Medline, Google Scholar

36 Kish SJ, Zhong XH, Hornykiewicz O, Haycock JW: Striatal 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine decarboxylase in aging: disparity between postmortem and positron emission tomography studies? Ann Neurol 1995; 38:260–264Google Scholar

37 Eidelberg D, Takikawa S, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Robeson W, Dahl R, Margouleff D, Moeller JR, Patlak CS, Fahn S: Striatal [18F]~dopa uptake: absence of an aging effect. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1993; 13:881–888Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Sawle GW, Colebatch JG, Shah A, Brooks DJ, Marsden CD, Frackowiak RS: Striatal function in normal aging: implications for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 1990; 28:799–804Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Martin WRW, Palmer MR, Patlak CS, Clane DB: Nigrostriatal function in humans studied with positron emission tomography. Ann Neurol 1989; 26:535–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Seeman P, Guan H-C, Niznik HB: Endogenous dopamine lowers the dopamine D2 receptor density as measured by [3H]raclopride: implications for positron emission tomography of the human brain. Synapse 1989; 3:96–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Young LT, Wong DF, Goldman S, Minkin E, Chen C, Matsumura K, Scheffel U, Wagner HN Jr: Effects of endogenous dopamine on kinetics of [3H]N-methylspiperone and [3H]raclopride binding in the rat brain. Synapse 1991; 9:188–194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Dewey SL, Smith GS, Logan J, Alexoff D, Ding Y-S, King P, Pappas N, Brodie JD, Ashby CRJ: Serotonergic modulation of striatal dopamine measured with positron emission tomography (PET) and in vivo microdialysis. J Neurosci 1995; 15:821–829Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Logan J, Schlyer D, Hitzemann R, Lieberman J, Angrist B, Pappas N, MacGregor R, Burr G, Cooper T, Wolf A: Imaging endogenous dopamine competition with [11C]raclopride in the human brain. Synapse 1994; 16:255–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Logan J, Angrist B, Hitzemann R, Lieberman J, Pappas N: Effects of methylphenidate on regional brain glucose metabolism in humans: relationship to dopamine D2 receptors. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:50–55Link, Google Scholar

45 Seeman P: Elevated D2 in schizophrenia: role of endogenous dopamine and cerebellum. Neuropsychopharmacology 1992; 7:55–57Medline, Google Scholar

46 Ross SB, Jackson DM: Kinetic properties of the accumulation of [3H]raclopride in the mouse brain in vivo. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1989; 340:6–12Medline, Google Scholar

47 Ginovart N, Farde L, Halldin C, Swahn C-G: Effect of reserpine-induced depletion of synaptic dopamine on [11C]raclopride binding to D2 dopamine receptors in monkey brain. Synapse 1997; 25:321–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 Pohjalainen T, Cravchik A, Gejman PV, Rinne J, Någren K, SyvÄlahti E, Hietala J: Antagonist binding characteristics of the human Ser311→Cys variant of dopamine D2 receptor in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 232:143–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Hernandez ML, De Miguel R, Ramos JA: Nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopaminergic activities were modified throughout the ovarian cycle of female rats. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 1991; 85:223–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 Xiao L, Becker JB: Quantitative microdialysis determination of extracellular striatal dopamine concentration in male and female rats: effects of estrous cycle and gonadectomy. Neurosci Lett 1994; 180:155–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Crowley WR, O'Donohue TL, Jacobowitz DM: Changes in catecholamine content in discrete brain nuclei during the estrous cycle of the rat. Brain Res 1978; 147:315–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Jori A, Cecchetti G: Homovanillic acid levels in rat striatum during the oestrus cycle. J Endocrinol 1973; 58:341–342Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 Favis CF, Davis BF, Halaris AE: Variations in the uptake of [3H]~dopamine during the estrous cycle. Life Sci 1977; 20:1319–1332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Morissette M, Di Paolo T: Sex and estrous cycle variations of rat striatal dopamine uptake sites. Neuroendocrinology 1993; 58:16–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Di Paolo T, Morissette P: Striatal dopamine agonist binding sites fluctuate during the rat estrous cycle. Life Sci 1988; 43:665–672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 Salokangas RK: Prognostic implications of the sex of schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142:145–151Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 Seeman MV: Current outcome in schizophrenia: women vs men. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986; 73:609–617Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 Hallonquist JD, Seeman MV, Lang M, Rector NA: Variation in symptom severity over the menstrual cycle of schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:207–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 HÄfner H, Riecher-Rossler A, An Der Heiden W, Maurer K, Fatkenheuer B, Loffler W: Generating and testing a causal explanation of the gender difference in age at first onset of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1993; 23:925–940Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60 Seeman MV: Gender and the onset of schizophrenia: neurohumoral influences. Psychiatr J Univ Ottowa 1981; 6:136–138Google Scholar

61 Seeman MV, Lang M: The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:185–194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62 Forrest AD, Hay AJ: The influence on sex on schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1972; 48:49–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63 Pearlson GD, Kreger L, Rabins PV, Chase GA, Cohen B, Wirth JB, Schlaepfer TB, Tune LE: A chart review study of late-onset and early-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1568–1574Link, Google Scholar

64 Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Ding Y-S, Pappas N, Shea C, Piscani K: Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996; 20:1594–1598Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar