Mental Health Care for Latinos: Mental Health Services for Latino Adolescents With Psychiatric Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The major objectives of this study were to examine the prevalence of mental disorders and the use of mental health services among Latino adolescents who were receiving services in at least one of five public sectors of care in San Diego County. METHODS: Survey data were gathered for a random sample of adolescents aged 12 to 18 years (N=1,164) who were receiving public-sector care. Mental disorders were assessed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, and use of mental health services was assessed with the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents. RESULTS: Rates of disruptive disorders were significantly lower among Latino adolescents than among white adolescents. Although more than half of the Latino sample received specialty mental health services, those with psychiatric disorders were significantly underserved compared with their white counterparts. Latino adolescents with psychiatric disorders entered specialty mental health services at a later age and had made significantly fewer specialty mental health service visits in the previous year. In multivariate analyses, Latino youths were significantly less likely than white youths to use specialty mental health services independent of diagnosis, gender, age, and the service sector from which they were selected. CONCLUSIONS: Public service systems need to ensure that Latino youths are appropriately assessed for disruptive disorders and that they are provided with appropriate specialty mental health care.

The consensus among mental health researchers is that a small proportion of adolescents with emotional or behavioral problems receive the mental health services they need (1,2,3,4,5,6). Although data for adults suggest that Latinos with serious mental disorders are significantly less likely to use mental health services than comparable white Americans or African Americans (7,8,9,10,11,12), little is known about whether there are significant disparities in the receipt of needed services among Latino adolescents compared with adolescents from other racial and ethnic backgrounds. Even less is known about whether there are disparities by ethnic or racial group in the delivery of mental health services to the high-risk adolescents who are in public systems of care. This question is an important one, given the high probability that such youths will experience chronic and long-term psychiatric and behavioral problems.

Research on the use of mental health services by adolescents is difficult and rare, partially because adolescents may receive services in multiple public sectors of care (3,13,14). Some studies suggest that Latinos may be underrepresented in specialty mental health programs (15,16) and public school programs for children with serious emotional disturbances (17,18), may receive fewer support services in child welfare (19), and may be overrepresented in the juvenile justice sector compared with white youths (20,21,22). McCabe and colleagues (23) found that Latino youths were the most consistently underrepresented in five public sectors of care in San Diego County. The Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) community surveys (6,24,25,26) found that youths in Puerto Rico were significantly less likely than youths in Atlanta, New Haven, and New York to receive mental health services from mental health specialists, in medical settings, and at school.

Research among adults suggests that the prevalence of mental disorders is low in recent-immigrant and unacculturated Latino populations and increases with the duration of residence in the United States (11,27,28,29,30). Studies of adults also suggest that less-acculturated Mexican Americans or those who are more recent immigrants are significantly less likely to receive needed mental health services than those who are more acculturated (31,32,33).

Some research suggests that youths from ethnic minorities who have behavioral health problems may be more underserved than white American children with the same problems (2,34,35,36,37) and that a person's racial or ethnic background is a more important predictor of use of outpatient services than are his or her observed problems or symptoms (38,39). However, few of these studies have included Latino youths, none have focused on services provided for high-risk youths with open cases in public-sector provider agencies, and none have examined the potential effects of acculturation on service use patterns.

The study we report here examined possible disparities in the prevalence of mental disorders and the receipt of mental health services between high-risk Latino, white, and African-American adolescents in a sample from five public sectors of care in a large county in Southern California.

Methods

Survey design

The Patterns of Care study obtained data on a simple random sample of 1,715 youths aged six to 18 years from open cases in five San Diego County public service sectors—mental health services, alcohol and drug programs, public school programs for children and adolescents with serious emotional disturbances, the child welfare sector, and the juvenile justice sector—during the last six months of county fiscal year 1996-1997. The sample was stratified by race or ethnicity (white, Latino, African American, and Asian or Pacific Islander) and by the level of restrictiveness of the care setting (for example, home versus aggregate care). Interviews were conducted with both a primary caretaker and the youth for 80 percent of the sample, with only the primary caretaker for 15 percent of the sample, and with only the youth for 5 percent of the sample. Written informed consent was obtained from the primary caretakers and emancipated youths (those not living with family or a caretaker) and written assent from youths living with family or a caretaker. Internal review board approval for the survey was received from the various academic and research institutions with which the researchers were affiliated and, as appropriate, from the boards of the various service sectors.

The overall completion rate was 66 percent of located and eligible adolescents. Additional details of the sampling procedure have been published previously (40). Only the adolescent component of the sample—those aged 12 to 18 years (N=1,164)—was examined for the study reported here. Youths who were classified as biracial or "other" were excluded from the analysis. To ensure accurate representation of the service-using population from which the sample was selected, the data were weighted and analyses conducted with STATA statistical analysis software (41).

Measurement

Respondents selected their major racial or ethnic identification from an extensive list of categories. Approximately 85 percent of the Latino youths were of Mexican origin.

Service use data were obtained through the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA). This structured interview was designed by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) workgroup to be used in surveys to assess the use of mental health and substance use services by youths (42,43) and was based on several existing instruments (4,44,45,46,47). Both adult and youth versions of the SACA obtain information about lifetime and past-year use of school-based, outpatient, and inpatient mental health and substance abuse services. The version used in this study was modified to allow us to obtain more detailed information on lifetime history of service use. We examined only use in the year preceding the interview as reported by either the parent or caretaker or by the youth.

Mental disorders were assessed through use of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-IV (DISC-IV). The DISC-IV is a structured diagnostic instrument designed for use by lay interviewers to assess the presence of DSM-IV diagnoses (48,49). Both adult and youth reports were obtained for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Only self-report data for the youths were collected for affective disorders (dysthymia, major depression, and mania) and anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic, separation anxiety, and social phobia). A description of the logic supporting the choice of diagnostic modules and the most appropriate respondents has been published previously (40). In sum, however, the decisions on which diagnostic modules to administer to which informants were based on research on agreement between youths and their parents that suggests that adolescents are the best informants for internalizing disorders (anxiety and depression) and that both parent and adolescent perspectives are needed to assess the full range of disruptive disorders (50,51).

Respondents were classified as having a given diagnosis if either the caretaker's report or the youth's self-report of symptoms met diagnostic criteria and at least one informant endorsed at least one moderate diagnosis-specific functional impairment (40). The DISC-IV was not available in Spanish at the time of the interview. As a result, no self-report diagnostic data were available for six Latino youths (2 percent) who were interviewed in Spanish and no data were available for 119 Latino caretakers (37.2 percent) who were interviewed in Spanish. The Spanish-language version is now available and is being administered in a two-year follow-up of the study respondents.

Results

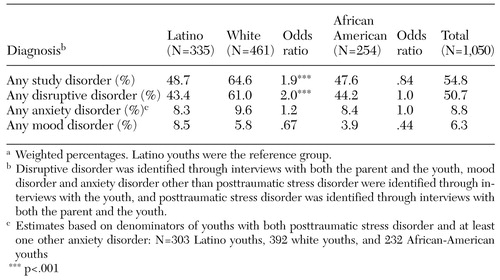

As indicated by the odds ratios listed in Table 1, the estimated prevalence of any current (past year) disorder and any current disruptive disorder was significantly lower among Latino youths than among white youths (48.7 percent compared with 64.6 percent and 43.4 percent compared with 61 percent, respectively). By far the most common disorders in this sample were disruptive disorders (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder), for which more than half of the total study sample had at least one diagnosis. White youths were twice as likely as Latino youths to report any disruptive disorder. No significant differences were found in the prevalence of any disorder or of any disruptive disorder between Latino youths and African-American youths. No significant differences were noted between Latino youths and white or African-American youths in the prevalence of any anxiety disorder or any mood disorder.

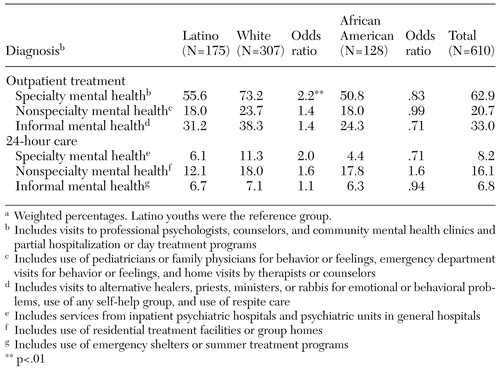

As shown in Table 2, white youths with one or more mental health diagnoses and moderate impairment were 2.2 times as likely as their Latino counterparts to receive specialty outpatient mental health services. The proportion of such Latino youths who reported using specialty outpatient services was 55.6 percent, compared with 73.2 percent of comparable white youths. No significant differences were found between Latino youths and white or African-American youths in the use of nonspecialty and informal outpatient mental health services.

The data in Table 2 also suggest that Latino adolescents with mental health diagnoses were not significantly different from other adolescents in their use of restrictive, 24-hour care in specialty mental health care (inpatient psychiatric hospital), nonspecialty mental health care (such as residential treatment facilities and group homes), or informal 24-hour mental health care (such as an emergency shelter or summer treatment program). However, there was a trend toward lower use of specialty mental health services and nonspecialty mental health services among Latino youths than among white youths (6.1 percent compared with 11.3 percent and 12.1 percent compared with 18 percent, respectively).

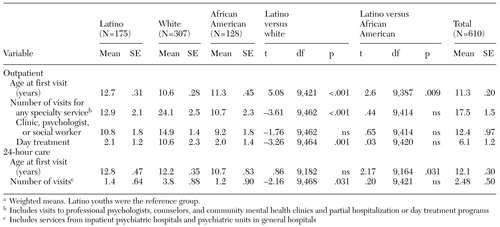

Racial or ethnic differences in age at first use of specialty mental health services and frequency of use in the past year for adolescents with one or more diagnoses and moderate impairment are summarized in Table 3. As can be seen in the table, the mean age at which a Latino youth with a current mental health diagnosis first visited an outpatient specialty mental health care provider was significantly greater than the age at which a comparable white youth or African-American youth made his or her first visit (12.7 years, 10.6 years, and 11.3 years, respectively). Once Latino youths were in the specialty mental health outpatient system, their mean number of visits was significantly lower than that of white youths (12.9 compared with 24.1). The same pattern of significantly lower frequency of service use for Latino youths than for white youths also held for visits to mental health care clinics or professional psychologists or social workers and visits for day treatment. No significant differences were found between Latinos and African Americans in the number of specialty outpatient mental health service visits.

The average age of receipt of first 24-hour specialty mental health care for Latino youths with one or more mental health diagnoses was 12.8 years, which was significantly greater than the first such visit for comparable African-American youths (10.7 years) but did not differ significantly from the age of first visit by white youths (12.2 years). The mean number of 24-hour specialty mental health care visits was significantly lower for Latino youths than for white youths and did not differ significantly from the number for African-American youths (1.4, 3.8, and 1.2, respectively).

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to further explore the power of race or ethnicity as a predictor of service use in the context of other possible predictors. The models used race or ethnicity, diagnosis, age, gender, and care sector to predict service use. Care sector was included because adolescents were likely to receive different mixes of services depending on which sector of care they were in when they were recruited into the study.

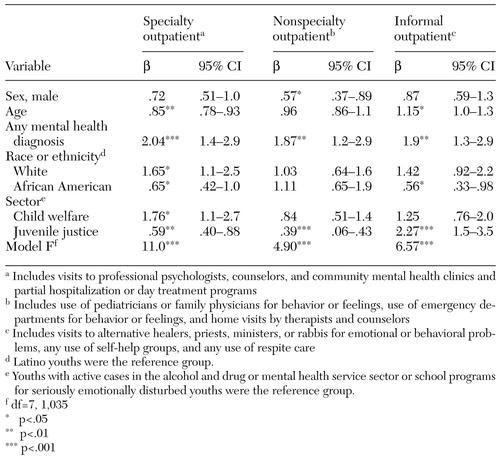

The data in Table 4 show that Latino youths were significantly less likely than white youths and significantly more likely than African-American youths to receive specialty mental health outpatient care. Other significant predictors of specialty outpatient care were any mental health diagnosis, younger age, and care sector: youths who had been recruited from the child welfare sector were more likely to receive specialty outpatient care and those recruited from the juvenile justice sector were less likely to receive specialty outpatient care than those who were recruited from substance abuse or mental health settings or school programs for children with serious emotional disturbances.

Racial or ethnic group was not a significant predictor of use of nonspecialty outpatient mental health services. Youths with a mental health diagnosis and adolescent girls were more likely to use nonspecialty outpatient mental health services and respondents recruited from the juvenile justice sector were less likely. Latino youths were significantly more likely to use informal outpatient mental health services than were African-American youths. No significant differences were found between Latino youths and white youths. Respondents with mental health diagnoses, older respondents, and respondents recruited from the juvenile justice sector were more likely to use such services.

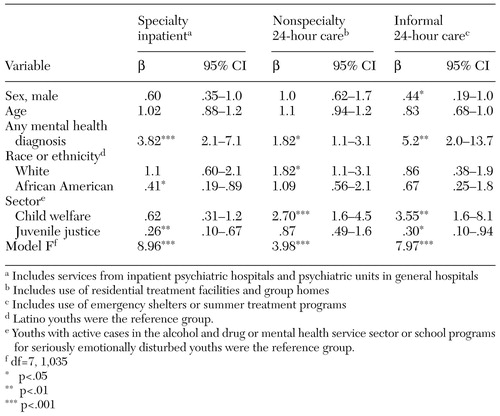

The results of logistic regression predicting care in a restrictive, 24-hour care environment are summarized in Table 5. Latino youths were significantly more likely than African-American youths to receive specialty inpatient mental health care. However, no significant difference was observed between Latino youths and white youths. By far the strongest predictor was any mental health diagnosis. Respondents who had been recruited from the juvenile justice sector were significantly less likely to receive specialty inpatient care than those who had been recruited from alcohol and drug programs, mental health programs, and school programs for seriously emotionally disturbed youths. White youths were 1.8 times as likely to have received nonspecialty 24-hour care as Latino youths, but no significant difference was found between Latino youths and African-American youths in this variable. Any mental health diagnosis and recruitment from the child welfare sector were also significant predictors of receipt of nonspecialty 24-hour care. No significant differences were found by racial or ethnic group in the receipt of informal 24-hour care. Having a mental health diagnosis, having been recruited from the child welfare sector, and being female were significant predictors of receipt of this form of care.

Discussion and conclusions

The prevalence of disruptive disorders (conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder) was very high (42.9 percent) among Latino youths in this public service-using sample, particularly compared with estimates of community rates. For example, 10.3 percent of respondents in the four MECA sites received DISC 2.3 diagnoses (meeting diagnosis-specific impairment criteria and having at least a mild score on the Children's Global Assessment Scale) (49). The estimate for Latino youths was significantly lower than that for white youths in this study (64.3 percent) and about the same as for other minority groups.

In terms of delivery of mental health services to youths in need, we examined the use of specialty mental health services by respondents with one or more diagnoses of a mental disorder and moderate impairment in the previous year. A majority of Latino youths (55.1 percent) who met these criteria did receive some form of outpatient specialty mental health care, and 6 percent received some form of inpatient specialty mental health care. As we expected, these rates of service use among Latino youths in public sectors of care are very high compared with rates in general populations of adolescents.

For example, in the Great Smoky Mountain studies (3), only 21 percent of a general population of youths had received some mental health services in the previous year, and only 8 percent had received any specialty mental health care. In the MECA studies (4), only 8.1 percent of all youths were estimated to have received some mental health specialty service in the previous year; among those with a DISC 2.3 diagnosis, 21.7 percent had used some nonschool mental health-related services and 27.3 percent had used some school-based mental health services.

In our study, some serious disparities were noted by racial or ethnic group in the receipt of mental health services among youths in need. The proportions of Latino youths with a diagnosable disorder and moderate levels of impairment who were receiving mental health care were significantly lower than the proportions of comparable white youths, 73.1 percent of whom received outpatient specialty mental health care and 11.2 percent of whom received inpatient specialty mental health care. Rates of use of specialty mental health services among African-American youths in need were similar to those among Latino respondents. It should also be noted that there was a trend of underrepresentation of Latino youths relative to white youths in outpatient and 24-hour nonspecialty mental health and informal mental health services. No significant differences were observed in the receipt of school-based care.

To further examine the possibility that Latino youths were underserved compared with white youths, we examined differences in the age of first reported use of specialty services and the frequency of use in the previous year. Latino youths reported entering specialty mental health services at a later age and receiving fewer specialty mental health services in the previous year than white youths.

Finally, multivariate analyses demonstrated that racial or ethnic group was a significant predictor of use of some forms of mental health services, independent of the effects of diagnosis, gender, age, and service sector. Perhaps most important, although having a psychiatric diagnosis was the best predictor of use of outpatient specialty mental health services, white youths were 1.65 times as likely to use such services as Latino youths. Only the sector of care was significantly predictive of inpatient specialty mental health care.

This study represents a unique attempt to understand whether there are disparities in the need for and delivery of mental health services to high-risk Latino youths in public sectors of care. Rates of mental disorders, particularly disruptive disorders, were found to be very high among Latino adolescents in public sectors of care compared with rates among youths living in the general community. However, a diagnosis of a disruptive disorder was twice as likely for white youths as for Latino youths. No significant differences in rates were found between Latino youths and African-American youths.

These findings suggest that there is a significant disparity in access to needed mental health services between Latino youths with mental disorders and other youths in public sectors of care. Latino clients and those from other racial or ethnic minorities obviously present a particular challenge to the appropriate delivery of specialty mental health care in public service sectors.

It should be emphasized that the data reported here concern only adolescents who had been active as clients in the public care system; the data cannot be generalized to community settings. It may be, as McCabe and associates (23) suggested, that Latino adolescents who reside in general community populations and need mental health services are significantly less likely than other youths to have access to mental health services but that once they enter a public sector of care they receive about the same amount of services as other youths.

Perhaps the major weaknesses of this study were the lack of a Spanish-language acculturation measure and a Spanish-language diagnostic assessment instrument. The former made the analysis of the effects of acculturation impossible. The latter effectively eliminated primarily Spanish-speaking youths and their parents from the analyses. Inclusion of the Spanish-speaking respondents would likely have resulted in even larger disparities, with even lower rates of disruptive disorders among Latino youths and, among those with disruptive diagnoses, even lower rates of use of outpatient specialty mental health services.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant U01-MH-55282 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Preparation of this article was also supported by National Research Service Awards F32-MH-11992-01 and F32-MH-11599-02. The authors thank Steven R. López, Ph.D., Javier Escobar, M.D., and Glorisa Canino, Ph.D., for their comments.

Dr. Hough is affiliated with the sociology department and Dr. Hazen and Dr. Yeh are affiliated with the psychology department of San Diego University. Dr. Hough, Dr. Hazen, Dr. Yeh, Dr. Soriano, Ms. Wood, and Dr. McCabe are with the San Diego Child and Adolescent Services Research Center. Dr. Hough is also with the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Diego, and the psychiatry department of the University of New Mexico. Dr. Soriano is also with the human development department of California State University, San Marcos. Dr. McCabe is also with the psychology department of the University of San Diego. Send correspondence to Dr. Hough at the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, 3020 Children's Way (MC5033), San Diego, California 92123 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on disparities in mental health care for Latinos.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of mental health diagnoses among Latino, white, and African-American youthsa

a Weighted percentages. Latino youths were the reference group.

|

Table 2. Past-year service use among Latino, white, and African-American youths with one or more mental health diagnoses and moderate impairmenta

a Weighted percentages. Latino youths were the reference group.

|

Table 3. Age at first use of specialty mental health service and frequency of use in the past year by Latino, white, and African-American youths with one or more mental health diagnoses and moderate impairmenta

a Weighted means. Latino youths were the reference group.

|

Table 4. Results of logistic regression analysis of use of outpatient services by Latino, white, and African-American youths

|

Table 5. Results of logistic regression analysis of use of inpatient services by Latino, white, and African-American youths

1. Angold A, Messer S, Stangl D, et al: Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Public Health 88:75-80, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al: Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs 14(3):147-159, 1995Google Scholar

3. Farmer E, Stangle D, Burns JB, et al: Use, persistence, and intensity: patterns of care for children's mental health across one year. Community Mental Health Journal 35:31-45, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Leaf PJ, Alegria M, Cohen P, et al: Mental health service use in the community and schools: results from the four-community MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:889-897, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. National Advisory Mental Health Council: National Plan for Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders. Rockville, Md, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1990Google Scholar

6. National Research Council: Understanding Child Abuse and Neglect. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1993Google Scholar

7. Hough RL, Landsverk JA, Karno M, et al: Utilization of health and mental health services by Los Angeles Mexican-Americans and non-Latino whites. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:702-709, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Jimenez A, Alegria M, Pena M, et al: Mental health utilization in women with symptoms of depression. Women and Health 25:1-21, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Padgett DK, Patrick CP, Burns BJ, et al: Women and outpatient mental health services: use by black, Latino, and white women in a national insured population. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:347-360, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L, et al: Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59:533-540, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:771-778, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Woodwards AM, Divinell AD, Arons BS: Barriers to mental health care for Hispanic Americans: a literature review and discussion. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:224-235, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Burns BJ, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al: Measuring child, adolescent, and family service use, in Evaluation of Mental Health Services for Children, edited by Bickman L, Rog D. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1992Google Scholar

14. Garland AF, Hough RL, Landsverk JA, et al: Multi-sector complexity of systems of care for youth with mental health needs. Children's Services: Social Policy, Research and Practice 4:123-140, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Bui K, Takeuchi DT: Ethnic minority adolescents and the use of community mental health care services. American Journal of Community Psychology 20:403-417, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pumariega AJ, Holzer CA, Nguyen H: Utilization of mental health services in a tri-ethnic sample of adolescents, in The Eighth Annual Research Conference Proceedings: A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base. Edited by Liberton C, Kutash K, Friedman R. Tampa, University of South Florida, 1993Google Scholar

17. Statistical Abstracts of the US (115th ed). Washington, DC, US Bureau of the Census, 1995Google Scholar

18. Elementary and Secondary School Civil Rights Survey. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, 1990Google Scholar

19. Courtney ME, Barth RP, Berrick JD, et al: Race and child welfare services: past research and future directions. Child Welfare 75:99-135, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

20. Garland A, Besinger B: Racial/ethnic differences in court-referred pathways to mental health services for children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review 19:1-17, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Garland AF, Hough RL, Landsverk JA, et al: Racial and ethnic variations in mental health care utilization among children in foster care. Children's Services: Social Policy, Research and Practice 3:133-146, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Wordes M, Bynum TS, Corley CJ: Locking up youth: the impact of race on detention decisions. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 31:149-165, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

23. McCabe K, Yeh M, Hough RL, et al: Racial/ethnic representation across five public sectors of care for youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 7:72-82, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Lahey BB, Flagg EW, Bird HR, et al: The NIMH Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) study: background and methodology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:855-864, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Fielding B, et al: Representativeness of clinical samples of youth with mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 106:3-14, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Flisher AJ, Kramer RA, Grosser RC, et al: Correlates of unmet need for mental health services by children and adolescents. Psychological Medicine 27:1145-1154, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Burnam MA, Hough RL, Escobar JI, et al: Current psychiatric disorders: Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:687-794, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Karno M, Hough RL, Timbers DM, et al: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:695-701, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Amaro H, Whitaker R, Coffman G, et al: Acculturation and marijuana and cocaine use: findings from HHANES 1982-1984. American Journal of Public Health 80:54-60, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Escobar JI: Immigration and mental health: why are immigrants better off? Archives of General Psychiatry 55:781-782, 1998Google Scholar

31. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RL, et al: Acculturation and the probability of use of health services by Mexican Americans. Health Services Research 24:237-257, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

32. Wells KB, Hough RL, Golding JM, et al: Which Mexican Americans underutilize health services? American Journal of Psychiatry 144:918-922, 1987Google Scholar

33. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:928-934, 1999Link, Google Scholar

34. Burns BJ: Mental health service use by adolescents in the 1970s and 1980s. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:144-150, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, et al: Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, Child and Adolescent Service System Program, 1989Google Scholar

36. Realmuto GM, Bernstein GA, Maglothin MA, et al: Patterns of utilization of outpatient mental health services by children and adolescents. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:1218-1223, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

37. Tuma JM: Mental health services for children: the state of the art. American Psychologist 44:188-189, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Cohen P, Hesselbart CS: Demographic factors in the use of children's mental health services. American Journal of Public Health 83:49-52, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Costello J, Janiszewski S: Who gets treated? Factors associated with referrals in children with psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 81:523-529, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses in youth across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:409-418, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. STATA Statistical Software, Release 7.0. College Station, Tex, STATA Corporation, 2001Google Scholar

42. Hoagwood K, Horwitz S, Stiffman A, et al: Concordance between parent's report of children's mental health services and service records: the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA). Journal of Child and Family Studies 9:315-331, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, et al: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. White paper, Center for Mental Health Services, Washington University, St. Louis, 2000Google Scholar

44. Ascher BH, Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, et al: The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA): description and psychometrics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 4:12-20, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Farmer EMZ, Angold A, Burns BJ, et al: Reliability of self-reported service use: test-retest consistency of children's responses to the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA). Journal of Child and Family Studies 3:307-325, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Cantwell DP, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Multimodal Treatment Study of Children With ADHD (the MTA): design challenges and choices. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:865-870, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

47. Weisz JR: The Referral Sequence and Problem Interview. Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Los Angeles, 1996Google Scholar

48. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al: NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:28-38, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, et al: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 2): description, acceptability, prevalences, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:865-887, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rhode P, et al: Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:610-619, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Herjanic B, Reich W: Agreement between child and parent on individual symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 25:21-31, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar