Gaps in Service Utilization by Mexican Americans With Mental Health Problems

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to ascertain the degree of underutilization of services for mental health problems among urban and rural Mexican American adults. METHOD: A probability sample (N=3,012) was used to represent the Mexican American population of Fresno County, California, and face-to-face interviews were conducted with the use of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were used to analyze the data on diagnosis and service utilization. RESULTS: Among the respondents with DSM-III-R-defined disorders, only about one-fourth had used a single service or a combination of services in the past 12 months, and Mexican immigrants had a utilization rate which was only two-fifths of that of Mexican Americans born in the United States. Overall use of mental health care providers by persons with diagnosed mental disorders was 8.8%, use of providers in the general medical sector was 18.4%, use of other professionals was 12.7%, and use of informal providers was only 3.1%. According to logistic regression analyses, factors associated with utilization of mental health services included female sex, higher educational attainment, unemployment, and comorbidity. CONCLUSIONS: Immigrants are unlikely to use mental health services, even when they have a recent disorder, but may use general practitioners, which raises questions about the appropriateness, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness of mental health care for this population. Several competing hypotheses about the reasons for low utilization of services need to be examined in future research.

The markedly lower rates of mental health service utilization among Mexican Americans have been a source of debate and speculation for decades (1–4). With few exceptions (5–8), empirical studies based on treatment data have consistently observed that Mexican Americans are a larger fraction of the general population than they are of patients in ambulatory mental health care. Today, utilization of health services is even more pertinent to health care planners because Mexican Americans are the most rapidly increasing and largest Hispanic ethnic group in the United States, and poverty levels have increased over the past decade, consistent with the disproportionate growth of the immigrant subpopulation. Increasingly, Mexican Americans are a national population, and given the shifts in public insurance coverage and managed care, the utilization behavior of Mexican Americans and the factors associated with their utilization and nonutilization of health services merit reassessment.

Historically, several explanations for differential utilization of services have been offered by researchers. Initial studies cited cultural differences in the perception of mental disorder that limited use of mental health care providers (9–13). The use of natural healers, especially curanderos/curanderas, was described as an indigenous treatment system that replaced the need for formal psychiatric care (14, 15). However, little systematic research was offered to support these explanations. The natural support systems of Mexican Americans were described as dense, nurturing, and encompassing, thereby lowering the vulnerability of Mexican Americans to dependence on formal health and mental health care providers (16, 17). The early ethnographic research suggested that there was little cultural precedent among Mexican Americans for considering the mental health specialty sector as an appropriate treatment source, even for the mentally ill. Presumably, Mexican Americans had little experience with American cultural assumptions about psychiatric disorders, their causes, and cures (18). However, the research of Karno and Edgerton in the 1960s (19, 20) demonstrated that Mexican Americans of low acculturation appeared to be committed to a view of psychiatric disorders that seems fundamentally compatible with contemporary American views on psychiatry: psychiatric disorders were physiological problems. Consequently, if treatment was sought for mental health problems, it could be expected that primary care physicians would be consulted. Another reason often cited for the disproportionate use of general physicians for mental health problems is somatization (21). The transformation of public health care policy and the health care industry poses special and unprecedented challenges for the Mexican American population because of their low insurance coverage and the persistence of cultural-linguistic barriers (22).

Since rates of mental health service utilization were, and continue to be, below population parity and far lower than those of non-Hispanic white people and African Americans, it was presumed that greater unmet needs exist among Mexican Americans. However, demonstrating an underutilization problem requires confirmation that rates of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans are equal to or higher than those among African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Mexican Americans with disorders must be either less likely to enter treatment or less likely to be treated within the mental health specialty sector. The psychiatric morbidity rates reported by the Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) project (23) and our own prevalence results (24) seem to answer the first part of the question; rates of psychiatric morbidity are significantly lower among immigrants.

This is an interesting turn in our understanding of the mental health status of ethnic groups with recent or ongoing histories of immigration. Whereas studies conducted decades ago promulgated the belief that immigrants had higher disorder rates than nonimmigrants, the research relied on data from state hospital admissions. The only major U.S. population survey of true prevalence, the Mid-Town Manhattan Study (25), used a nondiagnostic assessment method and only sampled in one location. Recent research has been more systematic and has expanded our understanding of the mental health epidemiology of internal population differences. Immigrants from Latin America, if they are not refugees, actually have lower rates of symptoms and disorders in comparison with U.S.-born persons of the same ethnic background (24, 26, 27). However, foreign birth offers no permanent immunity, because symptoms and disorder rates rise with increased time of residence in the United States (24). A parallel case can be found with Puerto Ricans, although they are migrants. For example, population rates of major depressive episode are higher in the continental United States than they are in Puerto Rico (28, 29).

This study was concerned with patterns of utilization of mental health services by Mexican Americans who have experienced recent disorders. There is insufficient research on this topic. This article reports findings from a representative sample interviewed face-to-face in their households. Coming some 12 years after the urban-based Los Angeles ECA study, our results amplify these earlier observations by providing comparative urban and rural samples and an opportunity to assess the implications of demographic changes over the past decade. Our study focused on the following fundamental questions. How likely are immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican Americans to use mental health services if they have psychiatric disorders? What are the current patterns of provider selection among these Mexican Americans? How are sociodemographic correlates (e.g., place of residence, birthplace, gender, age, education, family income, employment status) and psychiatric status (e.g., diagnosis and impairment level) associated with utilization? This study covered only individuals with disorders diagnosed according to DSM-III-R criteria, thereby eliminating the effect of lower psychiatric morbidity as an explanation for underutilization.

METHOD

Data for this study were collected in 1996 from urban, small town, and rural areas of Fresno County, California, and included respondents of Mexican origin only. The county of Fresno had a population of 764,810, and of these residents, 463,600 were living in the Fresno-Clovis metropolitan statistical area. Mexican Americans constitute 38.2% of the county population. To qualify for inclusion in the survey, the respondents were asked whether they or any parent or grandparent were born in Mexico. Data were collected by means of face-to-face interviews conducted by trained bilingual, bicultural interviewers using a computer-assisted interview survey. Data collection and entry were simultaneous. Respondents had the choice of an English- or Spanish-language interview, and written informed consent was requested. Respondents were not asked whether they resided in Fresno County as legal or illegal immigrants; they were informed that a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality, prohibiting any branch of the government from having access to interview information, had been obtained. The survey response rate was 90%.

The diagnostic protocol used in this study was the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (30, 31), a fully structured clinical interview that was developed jointly by the World Health Organization and the former U.S. Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration as the instrument of choice for large-scale epidemiologic research. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview conformed to DSM-III-R criteria, and utilization information was taken within the diagnostic sections of the interview protocol to anchor the use of services to specific psychiatric episodes.

The categories of care providers in the mental health specialty section were psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, psychiatric nurse, and other mental health professional. The general medical care provider category included family practitioner, general practitioner, internist, gynecologist, cardiologist, and other medical specialist. The other professional provider category included chiropractor, homeopath, priest, minister, rabbi, counselor, and nurse. The informal care provider category included folk healer (e.g., curandero), natural healer, spiritualist, practitioner of Santería, psychic, astrologer, and massage therapist.

The 508 subjects in the study were diagnosed as having one or more DSM-III-R disorders in the past 12 months; they were a subsample derived from the parent epidemiologic sample of 3,012 persons in the Fresno, Calif., metropolitan statistical area. The sample was selected under a fully probabilistic stratified, multistage cluster design. The 200 primary sampling units in each stratum were U.S. Census blocks or block aggregates selected with a probability proportionate to the size of their Hispanic population. In the second sampling stage, a quota of five households were randomly selected in each primary sampling unit. In the final stage, one person per household was randomly selected. To achieve the household-stage sample quota of at least five Hispanic households, blocks with low Hispanic density were aggregated with contiguous blocks into primary sampling units with a population of 30 or more Hispanics. Under this design, two-thirds of the primary sampling units remained as single census blocks, while the remaining third represented aggregation ranging from block pairs to entire census tracts. Up to five call-back attempts were made to recruit the selected subject into the study interview. The subjects were given a complete description of the study, and written consent was obtained.

Primary sampling unit quotas were, in some instances, either not met or slightly exceeded because of differential interview refusal rates. A system of primary sampling unit weights to adjust for the design requirement of equal sizes of the primary sampling units was developed. In addition, weights to adjust for household size (i.e., the number of eligible persons) were calculated, as well as weights to conform the sample to the census age-sex distribution. Given our multistage sampling design, all standard error estimates reported here are based on the first-order Taylor series approximation used by the SUDAAN statistical software (32).

RESULTS

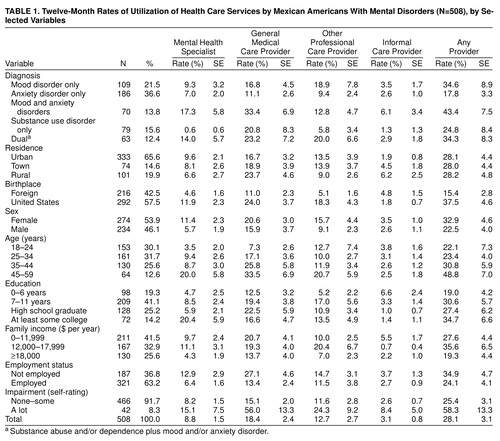

Table 1 presents the proportions of subjects with at least one use of a mental health service according to non-mutually-exclusive categories of provider type: mental health specialist, general medical care provider, other professional care provider, and informal care provider. As can be seen at the bottom of Table 1, the overall 12-month rate of utilization of any provider was 28.1% (SE=3.1). The highest utilization rate was for general medical care provider, followed by other professional, mental health specialist, and informal provider.

The first cross-classification in Table 1 shows utilization by diagnostic category. To facilitate analyses, discrete diagnoses were collapsed into the following five mutually exclusive categories: mood disorders only, anxiety disorders only, comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, substance abuse and/or dependence only, and dual diagnosis of substance abuse and/or dependence plus mood and/or anxiety disorder. As will be seen in the subsequent multivariate analyses, utilization appeared to be highest among the respondents with comorbid disorders, specifically those with co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders. However, subjects who experienced only a substance use disorder had the lowest utilization of all but the general medical provider type. Because our model variables were intercorrelated and category sample sizes were relatively small, the statistical significance of these variables is better addressed in the multivariate models that appear in Table 2.

Analysis of utilization by place of residence revealed that a very consistent 28% of the subjects consulted some provider; however, differences by provider type were suggested, with urban residents the most likely to use mental health specialists and rural residents the most likely to use general medical and informal care providers. The birthplace data show higher utilization rates among the U.S.-born for all providers other than informal. Female respondents showed consistently higher rates than male respondents. With respect to age, older subjects showed higher utilization of all except informal care providers. The highest mental health care utilization occurred among the most educated, while the highest informal provider utilization occurred among the least educated. The income distribution variable shows, first, that overall annual family income was quite low. In fact, only 25.6% of families were in the $18,000-or-higher category, which is approximately the official poverty breakpoint for a family of four persons. In general, the income data suggest curvilinearity of utilization, with the exception that the lowest income group were the most likely to use informal care providers. The data in Table 1 show a consistent pattern in which the unemployed reported higher utilization across providers. The last variable, self-reported impairment, was a response to the question “How much do problems with your (psychiatric symptom key phrase) limit you in doing things that most people your age are able to do—a lot, some, a little, or not at all?” Although it yielded a linear association across providers, this variable was dichotomized at the most severe level of “a lot.” Consistently higher utilization rates were reported by the respondents most impaired by mental health problems.

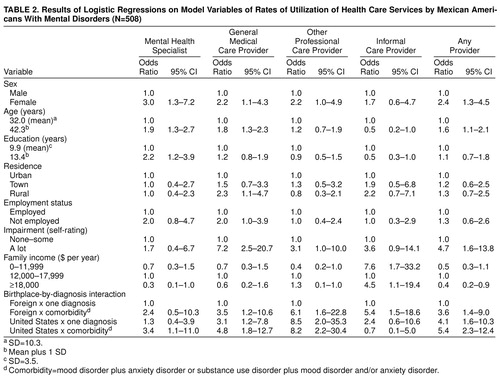

To address simultaneous and potential interaction effects, we used logistic regression to model utilization of each provider type as well as for overall utilization (Table 2). The outcomes of these analyses are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. First-order interactions among diagnosis, birthplace, and place of residence were examined, and only the diagnosis-by-birthplace interaction was found to be significant in some models. Multiple operationalizations of diagnoses yielded comorbidity as the best predictor. Comorbidity was operationalized as the combination of two mutually exclusive categories: mood disorder plus anxiety disorder or dual diagnoses, as shown in Table 1. Two or more specific diagnoses within the general categories of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders were treated as a single diagnosis for the purposes of these analyses. Interactions of birthplace, place of residence, and diagnosis with the remaining model variables were also tested, and none was found to be significant. For simplicity, the odds ratios for age and education were calculated with the use of their respective means as the reference category. The reciprocal of the odds ratio at 1 SD above the mean yields the odds ratio for 1 SD below the mean (the same for the reciprocals of the confidence limits). Because income suggested nonlinearity, it was divided into three ranges and treated as categorical.

The data in Table 2 indicate, first, that female respondents with disorders were more likely than males with disorders to use the services of all except the informal provider type. The sex difference was on the margin of the 0.05 significance level for other professional care utilization. Older persons were more likely to use mental health specialists and general medical care providers and less likely to use informal care providers. Place of residence yielded significant differences for general medical care providers, in that rural residents showed significantly higher utilization than urban residents. The unemployed respondents showed higher general medical care utilization than the employed. High impairment was clearly associated with higher utilization of general medical and other professional care but not mental health care. Income yielded somewhat complex outcomes. Respondents with the highest incomes used mental health specialists less than those in the middle-income range. There were no significant differences by income in utilization of general medical care, whereas for other professional care the pattern appeared linear, with respondents who had the lowest incomes showing the lowest utilization and those who had the highest incomes showing the highest utilization. Use of informal care providers was higher among the lowest- and highest-income subjects as compared with the middle-income group.

The last part of Table 2 shows the birthplace-by-comorbidity interactions. Supplemental analyses, which are not reported here, were performed with the use of alternate reference categories to facilitate interpretation. In general, the subjects who had comorbid diagnoses and who were U.S.-born were more likely to use mental health specialists. The effect of comorbidity on utilization was stronger among the U.S.-born. With respect to utilization of general medical care providers, the effect of comorbidity was more pronounced among the foreign-born. The same was true for utilization of other professionals. While the foreign-born with comorbid disorders were more likely to use informal care providers than were those with a single diagnosis, this was not true for the U.S.-born. In fact, the U.S.-born with comorbidity were not more likely to use informal care providers than even the foreign-born with a single diagnosis. The model for utilization of any provider type was fairly consistent with the separate models for all except the informal provider type and the effects of the income variable.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Among the respondents with psychiatric disorders, utilization of ambulatory care delivered by all types of providers in the past 12 months was far less likely to occur among the immigrants than among the U.S.-born Mexican Americans. Whereas 15.4% of immigrants who met DSM-III-R criteria had used some type of provider, including informal care providers, the respective proportion of the U.S.-born was 37.5%. Therefore, the utilization rate among the foreign-born respondents across all sectors of care was only about two-fifths of the rate among the U.S.-born.

It is informative to compare the ambulatory care findings of this study with those of other studies of Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic white respondents reported from the ECA program. However, these comparisons must be done with caution because of somewhat different recency criteria; the ECA program reported 6-month data, and the Fresno data are for 12 months. The five-site ECA program reported that about one-third of diagnosed individuals received no services, the Los Angeles ECA site reported that 51% of Mexican Americans received no care, and we report 71% with no care (an estimate that excludes informal care providers). The no-care group among immigrants in our study rises to 86%. Therefore, the fact that the ECA program reported 6-month data and we are reporting 12-month data suggests that the differences in rates are even more dramatic than these rate comparisons imply.

Utilization of mental health services by diagnosed respondents in the ECA program ranged from 8% to 12% and was reported as 8% among Mexican Americans at the Los Angeles site. We report a similar rate of 8.8%, with proportionately more mental health services used in urban than in rural areas, primarily by U.S.-born Mexican Americans with comorbid disorders. Whereas the Los Angeles ECA study reported a 6-month mental health service utilization rate of 3.1% for Mexican Americans with low acculturation, we report a 12-month rate of 4.6% for the foreign-born. Use of general medical care providers in the ECA study approached a rate of 60% for diagnosed respondents, the rate was 41% among Mexican Americans in the Los Angeles ECA study, and the rate in our study was 18.4%, with general medical provider treatment for mental health problems being significantly higher in rural areas.

An important explanation for Mexican Americans’ lower utilization of mental health services was based on the belief that emotional support systems partially displaced the need for formal care providers. We found that informal care providers were more likely to be used by the foreign-born, especially when they had comorbid disorders. However, among both the foreign- and the U.S.-born, use of informal services was low and certainly not a basis in either group for a “displacement” explanation of low utilization of mental health care services.

When immigrants do seek services, they are not likely to use family physicians, probably because they have no insurance, regular doctor, or source of care (33–35). The findings that they were as likely as the U.S.-born to use general physicians and that the utilization rate for general physicians was higher in rural areas suggest that the publicly financed rural public health clinic system is a frontline provider of care for Mexican American patients presenting with psychiatric disorders. Little attention has been given in past research to the importance of this provider system for identifying, treating, and referring individuals with psychiatric disorders. This finding of use of general physicians is reinforced by the minimal use of counselors by immigrants, who apparently are isolated from the American “culture of counselors” because of their low acculturation and physical isolation in rural areas. Moreover, it is very interesting to find that even among immigrants with high levels of impairment, the rate of mental health service utilization did not increase. This underscores the possibility of cultural inappropriateness—perhaps compounded by low access in rural areas—as an explanation for low utilization of mental health specialty care providers among immigrants who have disorders.

The total utilization rate for this sample of rural and urban Mexican Americans, excluding informal care providers, accounted for about one-fourth of all 12-month DSM-III-R-defined disorders in the population. How and why differences in place of birth result in differential risk of psychiatric morbidity and vastly differing patterns of care utilization within the same geographic location are intriguing questions. Despite these intrapopulation differences in selection of care providers, total utilization rates for addressing mental health problems were the same in rural, small town, and urban areas. Future research should focus on testing five competing explanations to determine their relative importance in the low service utilization among Mexican Americans with psychiatric disorders. Is utilization of mental health specialty care providers primarily influenced by 1) cultural beliefs about mental health problems, 2) ineffective and inappropriate therapies, 3) a dearth of Spanish-language mental health care providers, 4) access problems or other barriers, or 5) the protective effects of family and social network supports? The discrete effects of these explanatory factors have not been simultaneously estimated in any sample. This shortcoming has frustrated both scholarship and attempts to design service systems that equitably and effectively serve Mexican Americans. The advent of fixed prepayment based on numbers of persons covered rather than on services provided has made this circumstance particularly important to health policy. The assumed underutilization by Mexican Americans is ominous to providers of care because it implies that overcoming these problems in help seeking could dramatically increase demand for services and increase costs for them. Our data will permit us to address some of these issues in future papers, but a conclusive test of these explanations is beyond the scope of the present study design.

Received Dec. 18, 1997; revision received Sept. 29, 1998; accepted Nov. 20, 1998. From the University of Texas, San Antonio; the University of California, Berkeley; and California State University, Fresno. Address reprint requests to Dr. Vega, Metropolitan Research and Policy Institute, University of Texas, San Antonio, Downtown Campus, 501 West Durango Blvd., San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-51192 to William A. Vega, Principal Investigator.

|

|

1. Hough RL, Karno M, Burnam MA, Escobar JI, Timbers DM: The Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area research program and the epidemiology of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans. J Operational Psychiatry 1983; 14:42–51Google Scholar

2. Hough RL, Landsverk JA, Karno M, Burnam MA, Timbers DM, Escobar JI, Regier DA: Utilization of health and mental health services by Los Angeles Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:702–709Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wells KB, Hough RL, Golding JM, Burnam MA, Karno M: Which Mexican-Americans underutilize health services? Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:918–922Google Scholar

4. Report to the President From the President’s Commission on Mental Health, vol I: Number 040-000-00390-8. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1978Google Scholar

5. Jaco E: The Social Epidemiology of Mental Disorders: A Psychiatric Survey of Texas. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1960Google Scholar

6. López S: Mexican-American usage of mental health facilities: underutilization reconsidered, in Explorations in Chicano Psychology. Edited by Barón A Jr. New York, Praeger, 1981, pp 139–164Google Scholar

7. Trevino FM, Bruhn JG, Bunce H III: Utilization of mental health services in a Texas-Mexico border city. Soc Sci Med 1977; 13A:331–334Google Scholar

8. State of Colorado: Client Characteristics for all Admissions Episodes FY 1978–79. Denver, State of Colorado Department of Institutions, Division of Mental Health, 1980Google Scholar

9. Madsen W: Value conflicts and folk psychiatry in South Texas, in Magic, Faith, and Healing. Edited by Kiev A. New York, Free Press, 1964, pp 420–440Google Scholar

10. Martinez C, Martin HW: Folk diseases among urban Mexican Americans. JAMA 1966; 196:161–164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rubel A: Concepts of disease in Mexican American culture. Am Anthropologist 1960; 62:795–814Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Ruiz P: Culture and mental health: a Hispanic perspective. J Contemporary Psychotherapy 1977; 9:24–27Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Saunders L: Cultural Difference and Medical Care. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1954Google Scholar

14. Kiev A: Curanderismo: Mexican-American Folk Psychiatry. New York, Free Press, 1968Google Scholar

15. Torrey EF: The case for the indigenous therapist. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1969; 20:365–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Clark M: Health in the Mexican American Culture. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1959Google Scholar

17. Madsen W: The Mexican-Americans of South Texas. New York, Holt, Rinehart, & Winston, 1964Google Scholar

18. Creson DL, McKinley C, Evans R: Folk medicine in Mexican American culture. Dis Nerv Syst 1969; 30:264–266Medline, Google Scholar

19. Karno M, Edgerton R: Perception of mental illness in a Mexican American community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1969, 20:233–238Google Scholar

20. Edgerton R, Karno M: Mexican-American bilingualism and perception of mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1971; 24:236–290Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Kolody B, Vega WA, Meinhardt K, Bensussen G: The correspondence of health complaints and depressive symptoms among Mexican Americans and Anglos. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:221–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Barrera M: Mexican-Americans’ mental health service underutilization: a critical examination of some proposed variables. Community Ment Health J 1978; 14:35–45Medline, Google Scholar

23. Karno M, Hough RL, Burnam MA, Escobar JI, Timbers DM, Santana F, Boyd JH: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:695–701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among rural and urban Mexican Americans in California. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:771–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Srole L, Langner TS, Michael ST, Opler MD, Rennie TC: Mental Health in the Metropolis: The Midtown Manhattan Study, vol 1. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1962Google Scholar

26. Burnam MA, Hough RL, Karno M, Escobar JI, Telles CA: Acculturation and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. J Health Soc Behav 1987; 28:89–102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Vega WA, Rumbaut RG: Ethnic minorities and mental health. Annu Rev Sociol 1991; 17:351–383Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Canino GJ, Bird HR, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipek M, Bravo M, Martinez R, Sesman M, Guevara LM: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:727–735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Moscicki EK, Rae DS, Regier DA, Locke B: The Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: depression among Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans, in Health and Behavior: Research Agenda for Hispanics. Edited by Gaviria M, Arana JD. Chicago, Hispanic American Family Center, 1987, pp 145–159Google Scholar

30. Wittchen H-U, Robins LN, Cottler L, Sartorius N, Burke JD, Regier D: Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): the Multicentre WHO/ADAMHA Field Trials. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159:645–653; correction, 1992; 160:136Google Scholar

31. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Beiler GS: SUDAAN User’s Guide, Version 6.40, 2nd ed. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar

33. Trevino FM, Moss AJ: Health Insurance Coverage and Physician Visits Among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic People in the US: National Center for Health Statistics Publication. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1984Google Scholar

34. Berkanovic E, Telesky C: Mexican-American, black-American and white-American differences in reporting illnesses, disability, and physician visits for illnesses. Soc Sci Med 1985, 20:567–577Google Scholar

35. Trevino FM, Moyer ME, Valdez RB, Stroup-Benham CA: Health insurance coverage and utilization of health services by Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans, in Health Policy and the Hispanic. Edited by Furino A. Boulder, Colo, Westview Press, 1992, pp 158–170Google Scholar