Impact of Panic Attacks on Rehabilitation and Quality of Life Among Persons With Severe Psychotic Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study evaluated data from a sample of persons with severe psychotic disorders to determine whether those with and without comorbid panic attacks differed in rates of comorbidity of other psychiatric disorders, in quality of life, and in rehabilitation outcomes. METHODS: A total of 120 individuals with psychotic disorders were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, the General Health Questionnaire, the Global Assessment of Functioning scale, and several quality-of-life measures at baseline and four and a half months after they had participated in a social rehabilitation program. Multivariate analyses of variance and Pearson's chi square tests were used to compare baseline and follow-up scores between individuals who did and did not have panic attacks. RESULTS: Eighteen (15 percent) of the participants who had severe psychotic disorders also had panic attacks. Participants with this type of comorbidity had significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder, specific phobia, sedative abuse, polysubstance abuse, other substance abuse, and anorexia nervosa than participants who did not have panic attacks. Participants who had panic attacks also had poorer rehabilitative outcomes and poorer quality of life at baseline and at follow-up than participants who did not have panic attacks. CONCLUSIONS: These data are the first to show that comorbid panic attacks are associated with poorer rehabilitative outcomes and poorer quality of life among individuals with severe psychotic disorders than among those who have psychotic disorders without panic attacks. Panic attacks may be a valuable prognostic indicator among persons with psychotic disorders and may have implications for treatment and rehabilitation.

Panic attacks are common among individuals who have lifetime major depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders (1,2,3,4,5). The relationship between comorbid panic attacks and elevated rates of psychiatric comorbidity (1,2), poorer treatment response (3), and lower quality of life has been the focus of numerous investigations (4,5). In contrast, data on the impact of comorbid panic attacks on the prognosis, course of illness, and quality of life among individuals who have psychotic disorders are relatively scarce.

Several studies have revealed higher-than-expected rates of panic attacks among patients with psychotic disorders in psychiatric treatment settings (6,7,8). Studies have also shown that persons with co-occurring panic attacks and psychosis may have different responses to psychopharmacologic treatment than persons who have a psychotic disorder only (9). In fact, some reports recommend the use of alternative psychotherapies for optimal treatment of individuals who have co-occurring panic attacks and schizophrenia (10). However, no studies have been published on the impact of panic attacks on long-term treatment outcomes, the effectiveness of community-based rehabilitation programs, and quality of life among persons with psychotic disorders. Results of numerous previous studies suggest that panic attacks influence the long-term treatment outcomes of mood and anxiety disorders (3) as well as functional impairment and suicidality among persons without a psychiatric diagnosis (11). Therefore it is likely that these symptoms also affect the treatment outcomes and well-being of persons who have severe psychotic illness.

The goal of our study was threefold. First, we sought to determine the prevalence of comorbid panic attacks among a group of persons who had severe and persistent psychotic disorders. Second, we wanted to compare the sociodemographic characteristics and the presence of mood, anxiety, substance use, and eating disorders among persons who had psychotic disorders with and without panic attacks. Third, we wanted to compare the rehabilitation outcomes of participants who had psychotic disorders with and without panic attacks in terms of quality of life at baseline and four and a half months after they had participated in a social rehabilitation program.

On the basis of findings from previous studies in which the negative effects of panic attacks on the functioning of persons with psychosis were documented (1,2,3,4,5), we hypothesized that participants who had coexisting psychotic disorders and panic attacks would have higher rates of comorbidity of other psychiatric disorders and a poorer quality of life at follow-up than participants who had psychotic disorders without panic attacks.

Methods

The Partnership Project was a federally funded psychiatric rehabilitation study aimed at facilitating participation in a community-based treatment program for persons with serious and persistent mental illness (12,13). A total of 260 participants were recruited from the Connecticut Mental Health Center outpatient programs and other community-based mental health facilities in New Haven, Connecticut. The aim of the program was to improve the social integration of persons who had severe and persistent mental illness into the community by providing weekly connections with community volunteers who participated in leisure activities with the participants. The design, methodology, and qualitative data of the study, which was conducted between 1991 and 1996, have been described elsewhere (12,13).

Of the 260 individuals who participated in the Partnership Project, those who had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (N=120) were included in the study reported here. After the participants had been given a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained.

Diagnoses were made by trained interviewers using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (14,15). The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale (16,17), subscales from Lehman's Quality of Life scale (18,19), the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale (20,21), and the General Health Questionnaire (22) were used to evaluate participants at baseline and at follow-up.

Pearson's chi square tests were used to determine the differences in sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity between individuals who met criteria for psychotic disorders with and without panic attacks. All tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set at .05. Multivariate analyses of variance were used to compare scores on the General Health Questionnaire, the GAF scale, the CES-D scale, and subscales of the Quality of Life scale (purpose, mastery, and growth as aspects of well-being; satisfaction with school; and satisfaction with health) at baseline and at follow-up.

Editor's Note: This paper is part of a series on anxiety disorders edited by Kimberly A. Yonkers, M.D. Contributions are invited that address panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Papers should focus on integrating new information that is clinically relevant and that has the potential to improve some aspect of diagnosis or treatment. For more information, please contact Dr. Yonkers at 142 Temple Street, Suite 301, New Haven, Connecticut 06510; 203-764-6621; [email protected].

Results

Comorbidity of panic attacks

Of the 120 participants who had psychotic disorders, 18, or 15 percent, also had panic attacks. Of these, nine had schizophrenia and nine had schizoaffective disorder. One participant also met the criteria for brief reactive psychosis.

Sociodemographic characteristics

No significant differences were observed in sociodemographic characteristics between participants with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or other psychotic disorders, so the groups were combined.

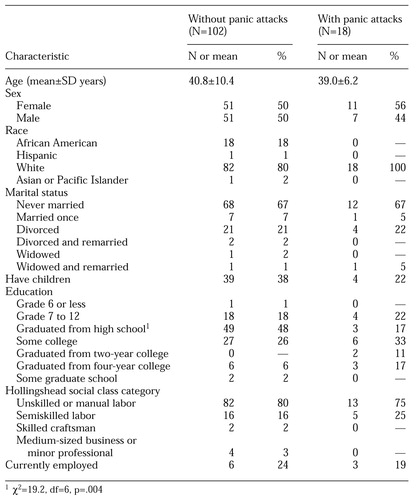

No significant differences were observed in gender, race, marital status, parenthood status, social class, or employment status between participants who did and did not have panic attacks (Table 1). Participants who had comorbid panic attacks were significantly less likely to have graduated from high school than those who did not.

Comorbidity of psychotic disorders

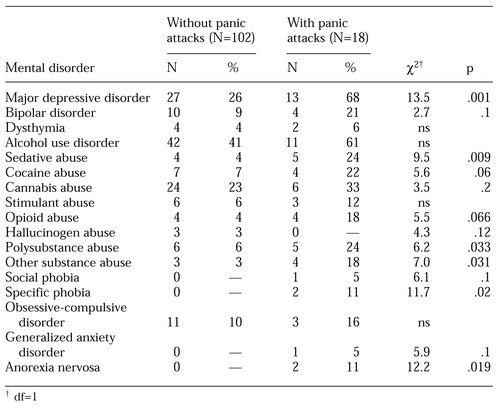

Participants who had psychotic disorders and comorbid panic attacks were significantly more likely than those who did not have panic attacks to have major depressive disorder, specific phobia, sedative abuse, polysubstance abuse, other substance abuse, or anorexia nervosa (Table 2). Rates of bipolar disorder, dysthymia, alcohol use disorder, cannabis abuse, stimulant abuse, hallucinogen abuse, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder were also higher among participants who had comorbid panic attacks than among those who did not. However, these differences were not statistically significant.

Rehabiliation and quality of life

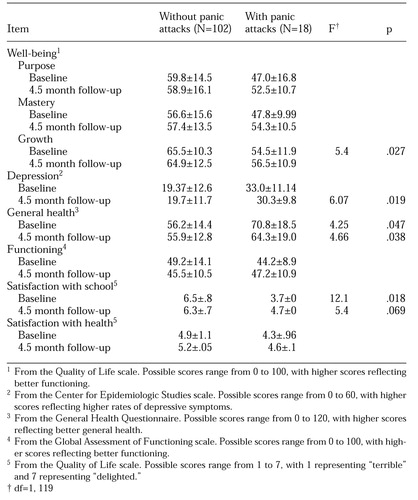

Compared with participants who did not have comorbid panic attacks, those who did have panic attacks reported a poorer quality of life at baseline and at four and a half months' follow-up on all Quality of Life subscales, as shown in Table 3. More careful inspection of the data revealed some interesting trends. Participants who had comorbid panic attacks appeared to improve on several of the measures between baseline and follow-up, although this improvement was not statistically significant.

Discussion

This study is the first to provide data suggesting that comorbid panic attacks have a detrimental impact on rehabilitation outcomes and quality of life among persons with severe psychotic disorders. These data indicate that panic attacks are prevalent—affecting about 15 percent of persons with psychotic disorders—and are associated with a significantly elevated risk of comorbid psychiatric disorders among patients with severe psychotic illness in community based treatment settings (6,7,8).

The reasons for the higher-than-expected prevalence of panic attacks among individuals with severe psychotic disorders are unknown. It is possible that panic attacks lead to psychosis, or that psychosis increases the risk of panic attacks. It is also possible that a third factor increases the risk of both panic attacks and psychosis. It is not inconceivable—given the differences in comorbid disorders, response to treatment, and course of illness among persons with comorbid panic attacks and psychosis—that comorbidity of panic attacks and psychosis reflects a different form or subtype of disorder within the schizophrenia spectrum (23,24). These potential pathways are not known and may merit further investigation.

The mechanism through which panic attacks lead to poorer outcomes in quality of life among individuals who have psychotic disorders is unclear. The lower scores in several key quality-of-life domains among participants in our study who had panic attacks are consistent with the association between comorbid panic attacks and the related impairment in functioning that has frequently been described among persons with major depression and anxiety disorders (25). It also is conceivable that panic attacks interfere with the response to psychopharmacologic treatment or with an individual's ability to tolerate various medications, resulting in poorer outcomes. Alternatively, it could be that poorer outcomes are predicted by higher rates of comorbid disorders among persons who have panic attacks, although the reasons for these comorbidities remain unknown.

The differences we observed in well-being and quality of life between baseline and follow-up, most of which were not statistically significant, show several potentially interesting trends that may provide useful direction for future study. Individuals who had comorbid panic attacks, although they had considerably lower scores at baseline and at follow-up, tended to show improvement from baseline to follow-up—in some cases by several points—on several measures, such as mastery as an aspect of well-being on the CES-D scale.

In contrast, the scores of individuals who did not have panic attacks changed very little; in some cases, the scores worsened slightly. However, because the sample was small and these changes may have reflected regression to the mean, our findings should be interpreted with caution. Notable, however, is the consistency with which this pattern was seen throughout the quality-of-life scores and the diversity of domains in which well-being was investigated—for example, depression and satisfaction with the pursuit of goals such as attending school—in an effort to reveal this pattern in both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric domains.

Interpretation of these data is largely speculative, and further empirical testing will be required. Limitations of this study include the use of a small sample of persons with comorbid panic attacks, which is likely to have contributed to the absence of statistical significance of many of the observed differences in quality of life between the two groups. For the same reasons, the quality-of-life outcomes were not corrected for multiple comparisons, which is also a significant limitation of the data. Our findings may be generalizable only to patients who receive community-based outpatient psychiatric treatment for psychosis.

The co-occurrence of panic attacks and psychosis has been relatively neglected as a target of study in clinical settings, for several possible reasons. First, clinicians may believe that panic attacks do not occur among persons who have schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Second, this particular form of comorbidity may be considered inconsequential in treatment outcomes among patients who have psychosis. Also, it is possible that the use of hierarchical diagnostic criteria obscures the prevalence of comorbid panic attacks among persons who have schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in clinical and research settings (23).

Conclusions

Our data suggest that panic attacks may affect the course of illness, the response to psychosocial intervention, and quality of life among persons with severe psychotic disorders, suggesting that this diagnostic pattern is clinically important. These findings should alert clinicians to the potential impact of comorbid panic attacks on treatment outcomes and quality of life among persons with psychotic disorders, highlighting the importance of diagnosing and treating both disorders when they co-occur (2,26). Additional research is needed to illuminate the sequence and timing of onsets, as well as the potential etiologic, neurobiological, and psychosocial mechanisms involved in these relationships.

Dr. Goodwin is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and the division of epidemiology of the Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Drive, Unit 43, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Stayner, Dr. Chinman, and Dr. Davidson are with the department of psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic differences of 120 study participants who had psychotic disorders with and without comorbid panic attacks

|

Table 2. Psychiatric comorbidity among 120 patients who had psychotic disorders with and without panic attacks

|

Table 3. Mean±SD scores on health and quality-of-life measures for 120 patients who had psychotic disorders with and without panic attacks

1. Kessler RC, Stang PE, Wittchen HU, et al: Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:801-808, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Andrade L, Eaton WW, Chilcoat HD: Lifetime comorbidity of panic attacks and major depression in a population-based study: age of onset. Psychological Medicine 26:991-996, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frank E, Shear MK, Rucci P, et al: Influence of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms on treatment response in patients with recurrent major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1101-1107, 2001Link, Google Scholar

4. Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, et al: Quality of life in panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:984-992, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, et al: Multiple anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic features. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:474-476, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Cosoff SJ, Hafner RJ: The prevalence of comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 32:67-72, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cutler JL, Siris SG: "Panic-like" symptomotology in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients with postpsychotic depression: observations and implications. Comprehensive Psychiatry 32:465-473, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Galynker I, Ieronimo C, Perez-Acquino A, et al: Panic attacks with psychotic features. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:402-406, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

10. Arlow PB, Moran ME, Bermanzohn PC, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic attacks in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 6:145-150, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

11. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, et al: Panic attacks in the community. JAMA 265:742-746, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Davidson L, Haglund KE, Stayner DA, et al: A qualitative study of supported socialization. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:275-292, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Davidson L, Stayner DA, Rakfeldt J, et al: Friendship and the restoration of community life: supported socialization for people with psychiatric disabilities, in Social Supports and Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Edited by Stastny P, Campbell J. New York, Wiley, in pressGoogle Scholar

14. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): I. history, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:624-629, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): II. multisite test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:630-636, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures 1:385-401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Husaini BA, Neff JA, Harrington JB: Depression in rural communities: validating the CES-D scale. Journal of Community Psychology 8:20-27, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Lehman AF, Postrado LT, Rachuba LT: Convergent validation of quality of life assessments for persons with severe mental illness. Quality of Life Research 2:327-333, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring the overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bodlund O, Kullgren G, Ekselius L, et al: Axis V-Global Assessment of Functioning Scale: evaluation of a self-report version. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:342-347, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Goldberg D, Cooper B, Eastwood MR: A standardized psychiatric interview for use in community surveys. British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine 24:18-23, 1970Medline, Google Scholar

23. Bermanzohn PC, Porto L, Arlow PB, et al: Hierarchical diagnosis in chronic schizophrenia: a clinical study of co-occurring syndromes. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:517-525, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hofmann S: Relationship between panic and schizophrenia. Depression and Anxiety 9:101-106, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, et al: Lifetime comorbidity of panic-depression in the National Comorbidity Survey: association with symptoms, impairment, course, and help-seeking. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:229-235, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Cutler J: Panic attacks and schizophrenia: assessment and treatment. Psychiatric Annals 24:473-476, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar