Influence of Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Symptoms on Treatment Response in Patients With Recurrent Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors tested the hypothesis that a lifetime history of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms predicts a poorer response to depression treatment.METHOD: A threshold for clinically meaningful panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms was defined by means of receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of total scores on the Structured Clinical Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum in a group of 88 outpatients with and without panic disorder. This threshold was then applied to a group of 61 women with recurrent major depression, who completed a self-report version of the same instrument, in order to compare treatment outcomes for patients above and below this clinical threshold.RESULTS: Women with high scores (≥35) on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report were less likely than women with low scores (<35) to respond to interpersonal psychotherapy alone (43.5% versus 68.4%, respectively). Women with high scores also took longer (18.1 versus 10.3 weeks) to respond to a sequential treatment paradigm (adding a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor when depression did not remit with interpersonal psychotherapy alone). This effect was only partially accounted for by the higher likelihood that patients with high scores required the addition of antidepressants. Although four domains from the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report were individually associated with a longer time to remission, only stress sensitivity emerged as significant in multivariate regression analyses.CONCLUSIONS: A lifetime burden of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms predicted a poorer response to interpersonal psychotherapy and an 8-week delay in sequential treatment response among women with recurrent depression. These results lend clinical validity to the spectrum construct and highlight the need for alternate psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic strategies to treat depressed patients with panic spectrum features.

Converging evidence indicates that patients with major depression and co-occurring anxiety features display more severe symptom profiles (1–4) and less favorable treatment outcomes (3–6, but also see reference 2) than patients with major depression alone. In particular, the existence of co-occurring panic features or a lifetime history of panic disorder has been linked to greater depression severity (5, 7–11), poorer psychosocial functioning (11), and poorer response to both psychotherapeutic (1, 12) and pharmacologic (1, 5, 11, 13, 14) depression treatments. For example, Feske et al. (12) found that recurrently depressed women with a history of panic disorder and higher levels of somatic anxiety were less likely to respond to interpersonal psychotherapy than depressed women without these panic features. Similarly, Brown et al. (1) found that depressed patients with a lifetime history of anxiety disorder exhibited a slower treatment response and less symptomatic improvement than depressed patients without lifetime anxiety—regardless of whether their depression was treated with psychotherapy or nortriptyline. Moreover, these researchers found that patients with a lifetime history of panic disorder exhibited the poorest treatment response.

From these findings, we hypothesized that anxiety, and specifically panic-like symptoms belonging to the panic-agoraphobic spectrum, are associated with poorer responses to both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. The term panic-agoraphobic spectrum (15) refers to a broad array of manifestations of panic disorder, including its core and most severe symptoms as well as a range of more subtle features related to the core condition. The latter may include temperamental traits, prodromal indicators, or residual symptoms. Cassano and colleagues (15–20) defined eight domains of the panic-agoraphobic spectrum: typical panic symptoms, anticipatory anxiety, and agoraphobia, together with an array of panic and phobic symptoms that are less frequently linked to panic disorder in the minds of clinicians (separation anxiety, stress sensitivity, substance sensitivity, reassurance seeking, and other illness-related phobias).

Assessment of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms in the context of treatment for another disorder has been emphasized as a means of identifying optimal treatment strategies, improving the clinician-patient relationship, and monitoring the course of illness (15, 18). The aim of the present report is to examine the association between scores on a self-report instrument designed to assess panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms and outcome of treatment of an acute episode of major depression. Specifically, we hypothesized that the endorsement of lifetime panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms would be associated with a poorer response to acute treatment.

Method

Patients

The study group consisted of 61 women participating in a larger randomized, controlled trial. Data reported here are drawn from the open, nonrandomized acute treatment phase of this protocol. As part of a sequential approach to acute treatment, all subjects were initially treated with interpersonal psychotherapy (21). If this alone failed to bring about a sustained remission, patients were subsequently offered treatment with antidepressant medication (fluoxetine) in addition to interpersonal psychotherapy.

To enter the study protocol, women between 20 and 60 years of age were required to be in at least their second episode of major depression, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder, Patient Edition (SCID-P) (22), with the immediately preceding episode having occurred within 10–130 weeks before the onset of the current episode. A minimum Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (23) score of 15 was also required. Patients were excluded if they met criteria for any other current axis I disorder (except for anxiety disorders, adult-onset dysthymia, or eating disorder not otherwise specified) or if they met full criteria for antisocial or borderline personality disorder. Women with a history of alcohol or substance abuse/dependence within the past 2 years were also excluded. The index episode could not be secondary to the effect of medically prescribed drugs, and women with significant medical illness were excluded from participation. Study participants had to be free of antidepressant medication for 2 weeks before study entry. Women who required inpatient treatment because of suicidal risk or psychotic symptoms were excluded (or withdrawn) from the study and referred for inpatient treatment. Those subjects who were subsequently offered pharmacotherapy were excluded if they had any condition that was considered incompatible with the use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

All recruitment, assessment, and treatment protocols were approved by the university’s biomedical institutional review board. All women initially eligible for the above protocol (including those eventually excluded) were given a complete description of the study and gave written informed consent for participation.

Acute Treatment Protocol

Patients were treated for 12–24 weeks to achieve remission of the acute depressive episode. The initial aim was to achieve remission with interpersonal psychotherapy alone. Patients were first treated with weekly interpersonal psychotherapy until remission was achieved or a determination of nonresponse was made according to the following algorithm: Hamilton depression scale score reductions of less than 33% from baseline after 8 weeks (including 4 weeks of twice weekly sessions, if necessary); Hamilton depression scale score reductions of less than 50% from baseline at week 12; or absence of full remission after 24 weeks of interpersonal psychotherapy alone.

At the earliest point at which a subject met the criteria for nonresponse to interpersonal psychotherapy alone, she was offered the option of having antidepressant pharmacotherapy added to her treatment regimen. Typically, pharmacotherapy began with 10–20 mg/day of fluoxetine. For patients who required the addition of medication treatment, mean time from study entry to medication start was 10.9 weeks (SD=4.8, range=2–18 weeks). Dose adjustments were made on the basis of individual responsiveness and tolerability. If the patient experienced difficulty with sleep after the medication was prescribed, the timing and dose of medication were adjusted. Two patients received adjunctive treatment with trazodone, and four patients received an adjunctive regimen of lorazepam for treatment of persistent insomnia during the acute phase. Two women with histories of nonresponse to fluoxetine were treated with sertraline, 50–250 mg/day.

Patients who did not meet remission criteria after 24 weeks of combined (interpersonal psychotherapy plus SSRI) treatment, and patients who experienced clinical deterioration or relapse were removed from the trial and offered other standard pharmacotherapies for depression.

Assessment

Depression status

Clinical status was monitored throughout the treatment protocol with weekly Hamilton depression scale score ratings completed by independent evaluators trained to maintain high levels of interrater reliability. Full clinical remission, achieved either with interpersonal psychotherapy alone or in combination with an SSRI, was defined by a Hamilton depression scale score of ≤7 for 3 consecutive weeks and a clinical consensus that the index episode had remitted. Following acute symptom remission, patients entered a continuation phase during which they continued to receive weekly treatment (interpersonal psychotherapy alone or with an SSRI) for 20 weeks, followed by a 24-month maintenance treatment phase. In the present report, we examined patients’ response to the acute treatment phase only.

Panic-agoraphobic spectrum

In a cross-sectional cohort of 61 patients currently active in the above treatment protocol, lifetime history of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms was assessed with the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report. This 114-item self-report scale is essentially identical in item content to the Structured Clinical Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum, which has been shown to display excellent psychometric properties (24). Total scores obtained through the interview and self-report formats have been found to be highly correlated in a cohort of 92 psychiatric outpatients and 20 normal comparison subjects (intraclass correlation=0.94). Items from the self-report scale assess impairment related to behaviors and experiences in the eight panic-agoraphobic symptom domains previously described for the full structured interview.

Statistical Analyses

Defining a panic-agoraphobic spectrum threshold

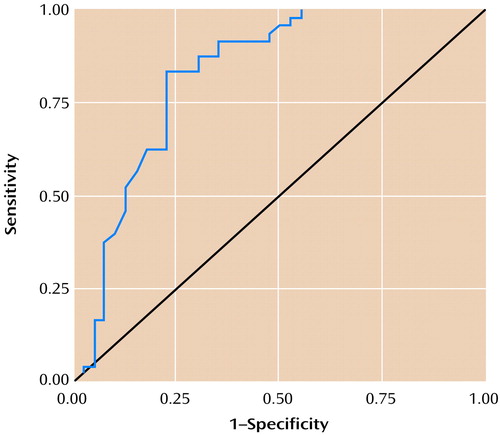

A preliminary analysis was conducted to define a clinically relevant threshold for panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms to use in outpatient psychiatric study groups. This was done by applying receiver operating characteristic analysis to an existing data set of 88 outpatients recruited through various clinics at the University of Pittsburgh, on whom Structured Clinical Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum (24) data were also available. Included in this cohort were outpatients diagnosed by means of the SCID-P (22) with 1) panic disorder but no history of major depressive disorder (N=9); 2) current obsessive-compulsive disorder but no history of panic disorder (N=15); 3) current major depressive disorder but no history of panic disorder (N=20); 4) current major depressive disorder and a history of panic disorder (N=31); and 5) a comparison group of healthy volunteers with no history of depression or panic disorder (N=13). The mean age of the study group was 35.5 years (SD=11.4, range=18–55), and the percentage of women was 68.2% (N=60). There was no difference in the total score on the Structured Clinical Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum between men and women (t=0.74, df=86, p=0.46).

The total score on the Structured Clinical Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum, which defines the number of items endorsed, was used as the test variable. Because no objective definition of the presence of clinically significant panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms is available, the “gold standard” for receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was the presence of SCID-P-defined panic disorder. The panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptom threshold was defined to lie somewhere below the threshold for diagnosable panic disorder. A reliable estimate of the optimal threshold for panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms was obtained by maximizing the sensitivity while keeping the specificity at an acceptable level. This allows one to capture more panic disorder cases and a number of patients in whom panic-agoraphobic symptoms are present to a moderate degree. We obtained an optimal threshold score of 35 with this criterion (sensitivity=0.875, specificity=0.700, positive predictive value=0.778). The area under the curve was 0.828 (SE=0.047) (Figure 1). We used the score of 35 or higher to characterize patients as having clinically significant panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms in subsequent analyses.

Effects on treatment outcome

The effect of a lifetime history of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms on depression treatment outcomes was assessed in a number of ways. First, panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms were defined as a dichotomous variable (present/absent). A chi-square test was performed to compare the proportion of women with high (≥) versus low (<35) Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores who responded to interpersonal psychotherapy alone. Next, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to compare the median time to remission between women above and below the panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptom cutoff score. The event “remission” was defined as the first of 3 consecutive weeks in which the patient’s Hamilton depression scale rating was 7 or lower, whenever this occurred (i.e., during interpersonal psychotherapy alone or following the addition of SSRI treatment).

Second, panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms were analyzed as a quantitative variable by considering the total Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report score and the individual domain scores. Given the sequential design of the current treatment protocol, in which patients who did not respond to interpersonal psychotherapy alone were offered the subsequent addition of fluoxetine, it was likely that patients who required the addition of antidepressant medication would display a longer time to remission than those who responded to interpersonal psychotherapy alone. To account for this treatment design, Cox survival regression models for time to remission were used, in which the effect of time to medication initiation was analyzed as a time-dependent covariate and the effect of Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report score as a fixed covariate (25). Analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 9.0 (Chicago, SPSS), and SAS 6.12 (Cary, N.C., SAS Institute).

Results

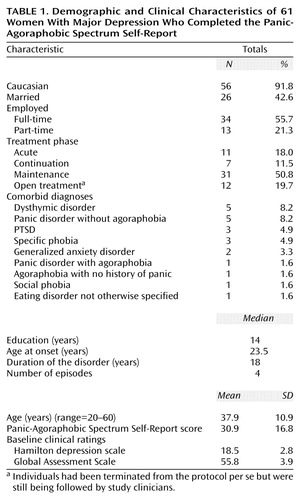

Seventy-one women representing a cross-sectional sample of the women who were active in the aforementioned protocol were invited to complete the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report. Of the 71 women approached, 61 returned completed questionnaires, for a response rate of 85.9%. Nonresponders did not differ from responders in terms of age, baseline severity, or treatment outcome indices. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 61 subjects who completed the self-reports are presented in Table 1. Of the participants, 18 (29.5%) met criteria for one or more current comorbid diagnoses at study entry (as determined by the SCID-P).

Of the 61 respondents, 23 (37.7%) were categorized as scoring high (i.e., 35 or higher) on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report. As would be expected, a greater proportion of these patients reported a lifetime history of panic disorder and/or agoraphobia than did those who scored below 35 on the measure (p=0.001, Fisher’s exact test). Only two (5.3%) of the 38 women with low scores on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report reported a lifetime history of panic and/or agoraphobia (one of whom met criteria at study entry), whereas nine (39.1%) of the women with high scores reported such a history (six of whom met criteria at study entry). That these proportions fall far short of 100% suggests that the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report cutoff of 35 captured a substantial number of subjects with elevated levels of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms that did not reach current or lifetime DSM-IV thresholds. Moreover, patients with high and low scores on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report did not differ in the number of nonpanic lifetime axis I diagnoses reported (Mann-Whitney U=349.0, N=59, p=0.13), which indicated that diagnostic differences between the groups were specific to panic.

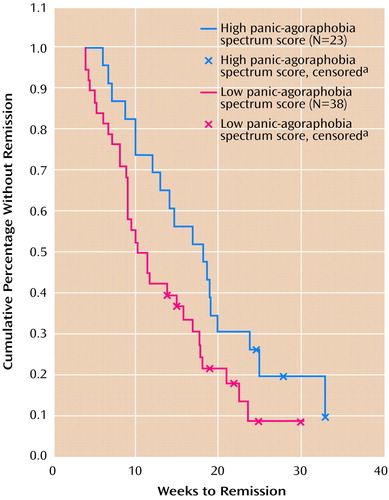

As predicted, women with high levels of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms were less likely to respond to interpersonal psychotherapy alone (χ2=3.92, df=1, p<0.05). Specifically, while 68.4% (N=26 of 38) of women with Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores below 35 responded to interpersonal psychotherapy treatment alone, only 43.5% (N=10 of 23) of women with high (≥) Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores showed a similar treatment response. A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that high scores were also associated with a longer median time to remission with sequential treatment (adding an SSRI when depression did not remit with interpersonal psychotherapy alone) than was seen in patients with low Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores (18.1 weeks versus 10.3 weeks, respectively; Breslow test=4.50, df=1, p<0.05) (Figure 2).

Women with high (≥35) versus low (<35) scores on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report were nearly identical on all baseline clinical severity indices (i.e., Hamilton depression scale score, Global Assessment Scale score, and duration of the index episode) and did not significantly differ in terms of race, education, marital status, or employment status (data available from Dr. Frank). Differences between subjects with high and low Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores with regard to current age (39.9 versus 36.6 years, respectively; t=–1.14, df=59, p=0.26), age of first depressive onset (25 versus 29.7 years; t=1.22, df=58, p=0.23), and median number of lifetime depressive episodes (five and three previous episodes, respectively) (Mann-Whitney U=280.5, N=59, p=0.056) also failed to reach statistical significance.

In a Cox survival regression model analysis, time to remission was found to be independently associated with the addition of medication and with total Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores. Specifically, we included in the model the total Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report score and a time-dependent covariate (time to medication initiation), which was set to zero for those who were not given an SSRI and to one for the rest of the patients at the time drug was started. The model fit the data significantly better than the baseline model, in which all covariates were set to zero (overall χ2=10.8, df=2, p=0.005). Since both score on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report and time to medication initiation were found to be significant correlates of time to remission (r=0.98, df=1, p=0.02, and r=0.32, df=1, p=0.02, respectively), we can conclude that even when controlling for the addition of medication treatment, higher levels of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms continued to show a significant association with longer time to remission.

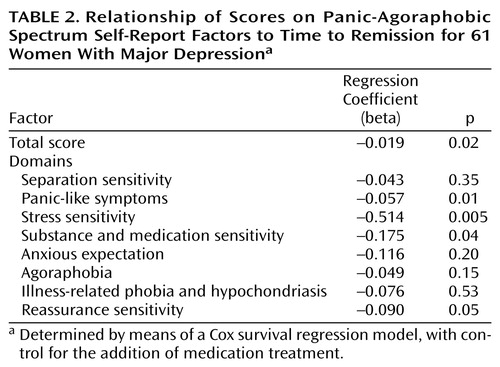

When analyzed separately with the above-mentioned technique, four domains of the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report (panic-like symptoms, stress sensitivity, reassurance sensitivity, and substance and medication sensitivity) were significantly associated with time to remission (Table 2). However, when all the domains were included in the Cox regression model by means of a forward stepwise procedure, only the stress sensitivity domain passed the entry criteria (p=0.05) and was retained in the model. This model fit the data significantly better than the baseline model (overall χ2=19.9, df=2, p=0.001). A backward stepwise procedure produced identical results.

Discussion

Reports of a lifetime history of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms were prevalent in this group of women with recurrent depression; more than one-third reported symptoms of clinical significance. As predicted, our findings indicate that panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms are negatively associated with treatment response for major depression. Recurrently depressed women with high levels of these symptoms took an additional 8 weeks to respond to sequential depression treatment (i.e., interpersonal psychotherapy alone or with the addition of fluoxetine) than did women with low levels of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms.

This delayed treatment response may have occurred for a number of reasons. First, patients with high (≥35) scores on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report were, in fact, less likely than patients with lower scores to respond to psychotherapy alone. As expected in the context of a sequential treatment protocol, subsequent addition of SSRI treatment was associated with a longer time to remission. However, the fact that women with high Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores were more likely to require the addition of pharmacotherapy does not entirely account for the delayed treatment response in this group, since a significant effect for panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms was apparent even after controlling for the effect of medication treatment.

Three limitations of the current study deserve attention. First, the study group was restricted to women. Given the female predominance in lifetime rates of both major depression and panic disorder, comorbidities between these disorders may have particular relevance for female patients. Whether the current findings will generalize to male patients, however, remains an empirical question. Second, assessments with the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report were conducted at a single point in time and, thus, represent the reports of patients in different phases of the larger treatment protocol. Patients with high and low scores on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report did not, however, significantly differ with regard to their current status in the study (χ2=3.47, df=3, p=0.33). Moreover, because the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report assesses lifetime rather than current experience of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms, the point at which assessments are administered should be somewhat less of a concern. Nonetheless, the cross-sectional nature of the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report assessment may have weakened the study results, since some patients—and perhaps those with the most severe panic-agoraphobic histories—may have dropped out of the study before assessment as a result of nonresponse, relapse, or refusal to take medication when interpersonal psychotherapy was not completely successful. Third, the current study group size did not allow us to conduct separate survival analyses examining time to remission for those patients who responded to interpersonal psychotherapy alone (N=35) and those who responded to interpersonal psychotherapy plus medication (N=16). We were, however, able to examine time to remission in the full cohort, controlling for the addition of medication treatment statistically.

Indeed, medication treatment and Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores displayed independent and noninteracting effects on treatment remission times. Hence, in line with the findings of Brown et al. (1) regarding the deleterious effect of lifetime anxiety in depressed patients treated with either interpersonal psychotherapy or nortriptyline, our results indicate that high levels of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms over the lifetime are associated with a delayed response to treatment whether or not fluoxetine is added to the patient’s treatment regimen.

Two alternate explanations for these findings can be addressed. The first argument is that the poor treatment response of patients with high Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores has little to do with coexisting panic symptoms per se but instead simply reflects the fact that these patients have a more severe form of depression or more axis I diagnoses in general. Contrary to this hypothesis, our results indicated that patients with high (≥35) and low (<35) Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores were nearly identical on all baseline depression severity indices and did not differ with regard to number of nonpanic lifetime axis I diagnoses. It is notable, however, that those with high scores reported more past depressive episodes than did those with low scores. Although this difference did not appear to affect the patients’ symptom presentation at study entry, the possibility that depressed patients with panic-agoraphobic spectrum features have a more recurrent depressive history is worthy of further examination.

A second alternate explanation is that differences in treatment outcome are driven solely by the subset of patients with current (N=7) or lifetime (N=11) diagnoses of DSM-IV panic disorder. Contrary to this hypothesis, a secondary survival analysis indicated that patients with high versus low Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report scores significantly differed in treatment outcomes even after controlling for lifetime DSM-IV panic history (log rank=4.39, p=0.04). These results support the incremental validity and prognostic utility of spectrum assessment beyond depression severity or DSM-IV panic comorbidity.

Categorical classification of psychopathology (such as in DSM-IV) often fails to capture the broader panoply of symptoms associated with various axis I disorders as well as related yet enduring temperamental features. Thus, the spectrum approach was developed to better characterize these subtle manifestations and to capture the continuum between the “core” symptoms of each disorder, as defined in the categorical diagnostic approaches, and the associated aura of symptoms characteristic of the core condition (15).

Attempts to assess coexisting panic features that rely solely on DSM-IV diagnosis of current or even lifetime episodes lack the sensitivity to capture a clinical picture that continuously emerges throughout development. As a clinical example, consider a woman who in her late teens experiences a few limited-symptom panic attacks. Although undiagnosed and untreated, these early and frightening experiences may trigger a variety of subsequent responses, such as an increased somatic focus, health concerns, fearful dependence, and social isolation. Over time, such responses may become patterned or trait-like; hence, early panic symptoms may “shape” subsequent personality development and represent a protracted diathesis for the experience of depressive episodes later in life (15). Indeed, as discussed by Frank et al. (18), diagnosable levels of core panic disorder symptoms may represent the “tip of the iceberg” of the full spectrum of related panic disorder symptoms, with the bulk of associated features hidden below the DSM-IV criteria threshold. An advantage of the spectrum approach lies in its ability to “cast a wide net” to capture these often overlooked yet clinically important features that may, in fact, represent prodromal, residual, or chronic forms of the disorder.

The current findings represent an important clinical validation of the panic-agoraphobic spectrum concept and measurement strategy. The Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report accurately discriminated between psychiatric outpatients with and without significant panic features and, in line with recent research (1, 5, 11–14), panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms were significantly associated with poor depression treatment outcomes. These findings support the clinical utility of the spectrum approach as an adjunctive assessment tool in clinical research and treatment. The self-report version of the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum assessment has the particular advantage of easy and brief (approximately 20 minutes) administration.

Used in combination with more traditional categorical assessment approaches (such as the SCID), the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report represents a sensitive tool for the evaluation of panic features that appear to diminish the effectiveness of traditional depression treatments. Thus, patients who evidence these features are likely to warrant special clinical attention. The current results suggest that different psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic strategies may be necessary to treat depressed patients with coexisting panic spectrum profiles in the optimal manner.

|

|

Presented in part at the 4th Annual Conference of Societ�taliana di Psicopatologia (SOPSI), Florence, Italy, March 3–7, 1999. Received Aug. 10, 1999; revision received Jan. 6, 2000; accepted Jan. 12, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Address reprint requests to Dr. Frank, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-49115 (Dr. Frank), MH-30915 (Dr. Kupfer), MH-18269 (postdoctoral training fellowship of Dr. Cyranowski), and grants from Pfizer USA (Drs. Frank and Shear) and Pfizer Italiana (Dr. Cassano).

Figure 1. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis Applied to Total Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Symptom Scores of 88 Outpatients With and Without Panic Disordera

aSensitivity was maximized with specificity kept at an acceptable level (see text) to determine optimal threshold (i.e., score on the Structured Clinical Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum) that would indicate the presence of clinically significant panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms

Figure 2. Time to Remission for 61 Women With Major Depression and High (≥35) or Low (<35) Scores on the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Self-Report

aData from patients in the open treatment phase of the study (see Table 1) were censored at the point at which patients were terminated from the study protocol.

1. Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ, Shear MK, Houck PR: Treatment outcomes for primary care patients with major depression and lifetime anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1293–1300Google Scholar

2. Joffe RT, Bagby RM, Levitt A: Anxious and nonanxious depression. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1257–1258Google Scholar

3. Clayton P: The comorbidity factor: establishing the primary diagnosis in patients with mixed symptoms of anxiety and depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(Nov suppl):35–39Google Scholar

4. Clayton PJ, Grove WM, Coryell W, Keller M, Hirschfeld R, Fawcett J: Follow-up and family study of anxious depression. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1512–1517Google Scholar

5. Coryell W, Endicott J, Winokur G: Anxiety syndromes as epiphenomena of primary major depression: outcome and familial psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:100–107Link, Google Scholar

6. Zung W, Magruder-Habib K, Velez R, Alling W: The comorbidity of anxiety and depression in general medical patients: a longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(June suppl):77–80Google Scholar

7. Coryell W, Endicott J, Andreasen NC, Keller MB, Clayton PJ, Hirshfeld RMA, Schefner WA, Winokur G: Depression and panic attacks: the significance of overlap as reflected in follow-up and family study data. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:293–300Link, Google Scholar

8. Grunhaus L: Clinical and psychobiological characteristics of simultaneous panic disorder and major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1214–1221Google Scholar

9. Grunhaus L, Pande AC, Brown MB, Greden JF: Clinical characteristics of patients with concurrent major depressive disorder and panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:541–546Link, Google Scholar

10. Johnson MR, Lydiard RB: Comorbidity of major depression and panic disorder. J Clin Psychol 1998; 54:201–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. VanValkenburg C, Akiskal HS, Puzantian V, Rosenthal T: Anxious depressions: clinical, family history, and naturalistic outcome—comparison with panic and major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 1984; 6:67–82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Feske U, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Shear MK, Weaver E: Anxiety as a predictor of response to interpersonal psychotherapy for recurrent major depression: an exploratory investigation. Depress Anxiety 1998; 8:135–141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Grunhaus L, Rabin D, Greden JF: Simultaneous panic and depressive disorders: response to antidepressant treatments. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 47:4–7Medline, Google Scholar

14. Grunhaus L, Harel Y, Krugler T, Pande AC, Haskett RF: Major depressive disorder and panic disorder: effects of comorbidity on treatment outcome with antidepressant medications. Clin Neuropharmacol 1988; 11:454–461Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Cassano GB, Michelini S, Shear MK, Coli E, Maser JD, Frank E: The panic-agoraphobic spectrum: a descriptive approach to the assessment and treatment of subtle symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(June suppl):27–38Google Scholar

16. Cassano GB, Rotondo A, Maser JD, Shear MK, Frank E, Mauri M, Dell-Osso L: The panic-agoraphobic spectrum: rationale, assessment, and clinical usefulness. CNS Spectrums 1998; 3:35–48Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Fagiolini A, Shear MK, Cassano GB, Frank E: Is lifetime separation anxiety a manifestation of panic spectrum? CNS Spectrums 1998; 3:63–72Google Scholar

18. Frank E, Cassano GB, Shear MK, Rotondo A, Dell-Osso L, Mauri M, Maser J, Grochocinski V: The spectrum model: a more coherent approach to the complexity of psychiatric symptomatology. CNS Spectrums 1998; 3:23–34Google Scholar

19. Miniati M, Mauri M, Dell-Osso L, Pini S, Mengali F, Shear MK, Maser JD, Grochocinski V, Frank E, Cassano GB: Panic-agoraphobia spectrum and cardiovascular disease. CNS Spectrums 1998; 3:58–62Google Scholar

20. Pini S, Maser JD, Dell-Osso L, Cassano GB: Origins of the panic-agoraphobic spectrum and its implications for comorbidity. CNS Spectrums 1998; 3:49–57Google Scholar

21. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

22. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

23. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Cassano GB, Banti S, Mauri M, Dell’Osso L, Miniati M, Maser JD, Shear MK, Frank E, Grochocinsky V, Rucci P: Internal consistency and discriminant validity of the Structured Interview for Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum (SCI-PAS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1999; 8:138–145Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Cox DR, Oakes DO: Analysis of Survival Data. London, Chapman & Hall, 1984Google Scholar