Normalization of Enhanced Fear Recognition by Acute SSRI Treatment in Subjects With a Previous History of Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The present study aimed to 1) assess facial expression recognition in subjects with a previous history of major depressive disorder relative to subjects with no history of depression and 2) characterize the effects of acute citalopram infusion on recognition performance for both groups. METHOD: Unmedicated euthymic women with a history of major depression and matched comparison subjects with no history of depression were given a facial expression recognition task following intravenous infusion of saline or citalopram (10 mg) in a double-blind, between-group design. RESULTS: Following saline infusion, subjects with a previous history of depression showed a selectively greater recognition of fear relative to the subjects with no history of depression. The abnormal fear processing observed in the subjects with a previous history of depression was normalized following citalopram infusion, an effect that was opposite to that seen with the subjects with no history of depression. CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest that increased recognition of fear is a trait vulnerability marker for depression and that this is normalized following a single dose of citalopram.

The highly recurrent nature of depressive illness indicates that vulnerability to this disorder may persist into periods of remission. Cognitive theories of depression suggest that this vulnerability takes the form of negative distortions in information processing (1). However, most studies that have used questionnaire measures have failed to show the existence of cognitive vulnerabilities in subjects whose depression was in remission (2). It is possible that subtle changes in the processing of emotional material may not be amenable to this kind of conscious description.

This investigation therefore used a measure of facial expression recognition to assess whether subjects with a previous history of depression show long-standing negative biases in social perception relative to subjects with no history of depression. In addition, we assessed the effects of a single dose of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram on these differences in emotional processing. We have argued previously that antidepressant drugs may work, in part, by reducing negative biases in perception and memory that are believed to maintain symptoms of depression and anxiety (3).

Method

Subjects

Twenty female subjects who had suffered at least two previous episodes of depression and 20 female volunteers who had never been depressed were recruited. All subjects were between the ages of 19 and 57 years and gave written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee.

Participants were screened with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Subjects with no history of depression were excluded from the study if they had any history of an axis I disorder. Subjects with a previous history of depression were excluded from the study if they had any significant axis I disorder apart from depression. The subjects with a previous history of depression had been euthymic for at least 6 months and medication-free for at least 3 months. The subjects with a previous history of depression and those with no depression history had similar scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (mean=1.9 [SD=0.7] and 1.7 [SD=0.9], respectively). Subjects were randomly allocated to receive intravenous citalopram (10 mg) or placebo, giving a total of four groups (10 subjects per group) that were tested using a double-blind design. These four groups were matched in terms of age in years (previously depressed subjects given placebo: mean=37.2 [SD=3.6]; never depressed subjects given placebo: mean=39.7 [SD=3.8]; previously depressed subjects given citalopram: mean=34.7 [SD=3.4]; never depressed subjects given citalopram: mean=37.7 [SD=3.8]) and weight in kilograms (previously depressed subjects given placebo: mean=64.5 [SD=2.5]; never depressed subjects given placebo: mean=64.6 [SD=2.8]; previously depressed subjects given citalopram: mean=68.7 [SD=3.1]; never depressed subjects given citalopram: mean=71.0 [SD=3.8]).

Procedure

The facial expression recognition task, described previously (3), featured examples of five basic emotions—happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust (4)—which had been averaged between neutral (0%) and each emotional standard (100%) in 10% steps, providing a range of emotional intensities. Each face was presented on a computer screen for 500 msec and was immediately replaced by a blank screen. Volunteers made their response by pressing a labeled key on the keyboard.

To assess the impact of subjective state changes on emotional processing, visual analogue scale ratings were collected for the variables: happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, anger, alertness, and anxiety in all 20 of the subjects with no history of depression and 17 of the subjects with a previous history of depression.

Subjects attended the laboratory at midday, having fasted from breakfast, and an intravenous cannula was inserted. After a 30-minute rest period, subjects received 10 mg citalopram (in 5 ml saline) or 5 ml saline, administered intravenously over 30 minutes. Subjects completed the facial recognition task 30 minutes after the end of the infusion, in line with previous work suggesting that plasma drug and prolactin levels are elevated from the end of the citalopram infusion for at least 2 hours (5). Subjective state was assessed at baseline and before the psychological testing.

Statistical Analysis

Accuracy in the facial expression recognition task was analyzed by using three-way split-plot analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with the between-group factors of drug and depression history and the within-subjects factor of facial expression. Subjective state was also analyzed with split-plot ANOVAs with drug, group, and time of assessment as factors. Significant interactions were analyzed further by using simple main effect analyses, and covariates were included as appropriate.

Results

Subjective State

Subjects with a previous history of depression tended to rate themselves as more anxious throughout the test (F=6.1, df=1, 33, p=0.02). Anxiety ratings remained higher following citalopram infusion relative to placebo infusion (drug-by-time interaction: F=4.6, df=1, 33, p=0.02); this effect tended to be more pronounced in the subjects with a previous history of depression (group-by-drug-by-time of test: F=3.7, df=1, 33, p=0.06). All other mood ratings were not significantly affected by drug or by previous history of depression (p>0.40).

Facial Expression Recognition Accuracy

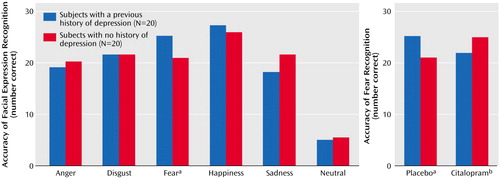

The group-by-drug-by-emotional expression interaction was significant in the three-way ANOVA (F=3.1, df=5, 180, p=0.01) performed on these data. The group-by-drug interaction was significant in terms of fear (F=13.0, df=1, 36, p=0.001) but not for any of the other facial expressions (all p≥0.20). The subjects with a previous history of depression showed higher baseline levels of fear recognition (under placebo) relative to the subjects with no depression history (Figure 1). Fear recognition in the subjects with a previous history of depression did not correlate with anxiety (r=–0.30, df=18, p=0.50) ratings, and the significant difference between these two groups was not affected by the inclusion of these scores as a covariate (F=6.4, df=1, 17, p=0.02). The heightened recognition of fear was reduced in the subjects with a previous history of depression receiving citalopram (Figure 1) to the level of fear processing seen in the subjects with no depression history under baseline conditions. In subjects with no history of deprssion, citalopram administration facilitated the recognition of fear relative to placebo (Figure 1). Hence, while acute citalopram administration increased fear recognition in the subjects with no history of depression, it normalized the higher levels of fear recognition seen in the subjects with a previous history of major depression.

Discussion

Subjects whose depression was in remission showed an increase in the perception of fearful facial expressions that was normalized following a single dose of the SSRI citalopram. These findings are in line with the idea that cognitive vulnerabilities persist into periods of remission from mood disorder (1) and that these kinds of cognitive changes are sensitive to antidepressant administration (3). This response was opposite to the facilitation of fear processing seen after citalopram administration in the subjects with no history of depression, suggesting that responses may be dependent on baseline levels of performance.

Subjects with a previous history of depression showed greater recognition of fearful faces relative to matched subjects with no depression history under the placebo condition. Enhanced processing of ambiguous negative facial expressions has been observed in acute depression (6) and was found to be predictive of later relapse (7), although these studies did not differentiate between different negative facial expressions such as fear and anger. Recently, euthymic patients with bipolar II disorder were also found to show more accurate recognition of fearful facial expressions (8). Together, these results suggest that enhanced recognition of negative facial expressions, particularly of fear, may be a trait vulnerability marker for mood disorder.

The amygdala appears to play a particular role in the processing of fear-relevant cues, including fearful facial expressions (9). The present enhancement in fear processing in the subjects with a previous history of depression is therefore consistent with evidence implicating a role for the amygdala in depression. Increased resting cerebral blood flow in the amygdala has been reported in familial depressive disorder (10), while increased activation of the left amygdala was observed during nonconscious presentation of fearful faces in acutely depressed patients (11). Abnormal amygdala activation is seen to normalize during antidepressant treatment with symptom remission (11), although resting metabolism remains elevated in unmedicated remitted patients (10). The present results suggest a possible functional consequence of these neural abnormalities.

The current findings suggest that it may be possible to integrate theories of antidepressant drug action with cognitive approaches to depression to formulate a better understanding of how pharmacological treatments interact with the neural systems underlying emotional processing. The fact that antidepressant administration can normalize negative biases seen in subjects with a previous history of depression has implications for the mode of action of maintenance antidepressant treatment in those at risk of recurrent mood disorder.

Received Jan. 7, 2003; revision received June 11, 2003; accepted June 13, 2003. From the University Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital. Address reprint requests to Dr. Harmer, Neurosciences Building, University Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital, Oxford OX3 7JX; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Accuracy of Facial Expression Recognition in Subjects With a Previous History of Depression and Subjects With No History of Depression and Change in Fear Recognition Accuracy Following Citalopram Infusion

aSignificant difference between groups (F=6.7, df=1, 18, p=0.02).

bSignificant effect of citalopram in the recovered depressed patients (F=8.7, df=1, 18, p=0.009) and in the comparison group (F=5.5, df=1, 18, p=0.03).

1. Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G: Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, Guilford, 1979Google Scholar

2. Parker G, Roy K, Eyers K: Cognitive behavior therapy for depression? Choose horses for courses. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:825–834Link, Google Scholar

3. Harmer CJ, Bhagwagar Z, Perrett DI, Völlm BA, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM: Acute SSRI administration affects the processing of social cues in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:148–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ekman P, Friesen WV: Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976Google Scholar

5. Attenburrow MJ, Mitter PR, Whale R, Terao T, Cowen PJ: Low-dose citalopram as a 5-HT neuroendocrine probe. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001; 155:323–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Gur RC, Erwin RJ, Gur RE, Zwil AS, Heimberg C, Kraemer HC: Facial emotion discrimination, II: behavioral findings in depression. Psychiatry Res 1992; 42:241–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bouhuys AL, Geerts E, Gordijn MC: Depressed patients’ perceptions of facial emotions in depressed and remitted states are associated with relapse: a longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:595–602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lembke A, Ketter TA: Impaired recognition of facial emotion in mania. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:302–304Link, Google Scholar

9. Calder AJ, Lawrence AD, Young AW: Neuropsychology of fear and loathing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001; 2:352–363Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Drevets WC, Videen TO, Price JL, Preskorn SH, Carmichael ST, Raichle ME: A functional anatomical study of unipolar depression. J Neurosci 1992; 12:3628–3641Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA: Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:651–658Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar