Impaired Recognition of Facial Emotion in Mania

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Recognition of facial emotion was examined in manic subjects to explore whether aberrant interpersonal interactions are related to impaired perception of social cues. METHOD: Manic subjects with bipolar I disorder (N=8), euthymic subjects with bipolar I (N=8) or bipolar II (N=8) disorder, and healthy comparison subjects (N=10) matched pictures of faces to the words “fear,” “disgust,” “anger,” “sadness,” “surprise,” and “happiness.” RESULTS: The manic subjects showed worse overall recognition of facial emotion than all other groups. They showed worse recognition of fear and disgust than the healthy subjects. The euthymic bipolar II disorder subjects showed greater fear recognition than the manic and euthymic bipolar I disorder subjects. CONCLUSIONS: Impaired perception of facial emotion may contribute to behaviors in mania. Impaired recognition of fear and disgust, with relatively preserved recognition of other basic emotions, contrasts with findings for depression and is consistent with a mood-congruent positive bias.

Mania is an altered mental state during which human behavior is dramatically transformed. Symptoms include grandiosity, talkativeness, racing thoughts, and disinhibition. Mania can yield indiscriminate enthusiasm for interpersonal interactions, which can profoundly disrupt social function. Bipolar I disorder is primarily differentiated from bipolar II disorder by involving severe (mania) rather than mild to moderate (hypomania) mood elevation.

There are sparse data regarding the processing of facial emotion in mania. A single study (1) showed right hemispheric bias in 10 hypomanic or manic subjects judging faces as “happy” versus “sad.” When depressed, one rapid-cycling patient with bipolar II disorder judged neutral faces as sad and sad faces as more sad but rated happy faces similarly across mood states (2). A patient with hypomania secondary to right thalamic infarct had impaired recognition of “negative emotions,” such as fear, but preserved recognition of “positive emotions,” such as happiness (3).

We examined recognition of facial emotion in primary mania for all six basic emotions: fear, disgust, anger, sadness, surprise, and happiness. These emotions are associated with distinctive facial expressions recognizable across cultures (4). We hypothesized that recognition of facial emotion is worse in manic subjects than in healthy comparison and euthymic bipolar subjects.

Method

Eight manic inpatients and 16 euthymic bipolar outpatients (eight with bipolar I disorder, eight with bipolar II disorder) at Stanford Hospital and Clinics were diagnosed by DSM-IV criteria. Ten healthy volunteers were identified by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and II Disorders, version 2.0. The exclusion criteria for the healthy volunteers also included having any first-degree relative with a psychiatric or substance abuse disorder. Mood states were confirmed by scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale (5) (mania, score≥20; euthymia, score<10) and scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (euthymia, score<10). All eight of the manic subjects had psychotic symptoms; all had grandiose delusions, five had formal thought disorder, and none had hallucinations. All of the subjects provided written informed consent before participating in this study, which was approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Human Subjects Research.

The subjects were shown photographs of different individuals displaying one of six different basic emotions (6). Each photograph was accompanied by a list of these six emotions, and the subjects were asked to identify the word that best described the face being presented. Thirty-three stimuli were presented in the same order for each subject, with no feedback given during or after the task and no time limit.

Statistical analyses used StatView 5 software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Group differences in overall recognition of emotion were assessed by Mann-Whitney U tests. To evaluate performance on recognition of individual emotions and account for multiple comparisons, a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of rank was applied to each emotion, and only the emotions for which there were significant differences were then analyzed with Mann-Whitney U tests. A significance threshold of p≤0.025 was used to attenuate the risk of type I error. Exact p values were obtained from tables reporting critical values of the Mann-Whitney U distribution. Friedman’s test was used to assess rank order of individual emotions within each group. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between performance and scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale.

Results

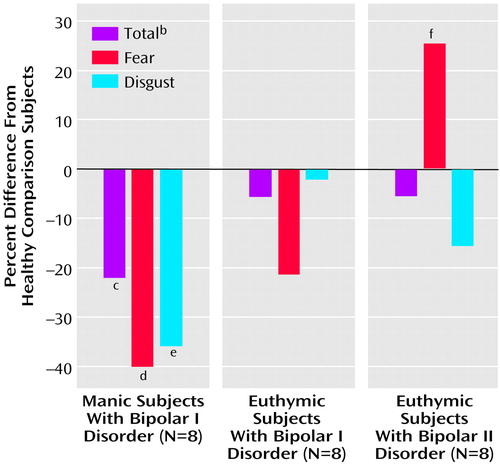

As shown in Figure 1, the manic subjects had worse overall recognition of facial emotion than the healthy comparison subjects (Mann-Whitney U=78, N1=8, N2=10, p<0.0005), the euthymic patients with bipolar I disorder (Mann-Whitney U=58, N1=8, N2=8, p=0.003), and the euthymic patients with bipolar II disorder (Mann-Whitney U=56, N1=8, N2=8, p<0.01). They also performed worse than the healthy comparison subjects on recognition of fear (Mann-Whitney U=63, N1=8, N2=10, p=0.025) and disgust (Mann-Whitney U=69, N1=8, N2=10, p=0.005). The manic subjects performed worse than the euthymic patients with bipolar I disorder on recognition of disgust (Mann-Whitney U=54, N1=8, N2=8, p<0.025) and worse than the euthymic patients with bipolar II disorder on recognition of fear (Mann-Whitney U=58, N1=8, N2=8, p=0.003). The manic subjects most consistently mistook fear for surprise (17 of 23 total errors, 74%) and disgust for anger (14 of 17 total errors, 82%).

Performance of the manic subjects on other individual emotions was not significantly different from that of the healthy comparison subjects. Of note, the manic subjects did not make a single error in recognizing happy faces, and this was not true for any other emotion category. The manic subjects performed the worst on fear, then disgust, anger, surprise, sadness, and happiness (Friedman ranking, p=0.003) and showed an inverse correlation between recognition of sadness and score on the Young Mania Rating Scale (Spearman’s r=–0.45, z=–2.61, p=0.009). Recognition of other emotions did not significantly correlate with scores on the Young scale.

The performance of the euthymic subjects with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder was similar to that of the healthy comparison subjects across all emotions. However, the euthymic subjects with bipolar II disorder performed significantly better on fear recognition than the manic patients (Mann-Whitney U=58, N1=8, N2=8, p=0.003) and the euthymic subjects with bipolar I disorder (Mann-Whitney U=51, N1=8, N2=8, p=0.025) and numerically better on fear than the healthy subjects (Mann-Whitney U=51, N1=8, N2=10, p=0.10) (Figure 1). The better recognition of fear by the euthymic subjects with bipolar II disorder did not appear to be due to overcalling fear, as the “fear error” (number of times nonfear faces were linked to “fear”) did not differ significantly across groups.

Discussion

Manic patients performed significantly worse than healthy subjects on recognition of fearful and disgusted faces. These findings contrast with the negative bias reported for depression (7), which has been associated with impaired recognition of happy faces and preserved recognition of fearful, angry, sad, and disgusted faces. These results may in part explain clinical behaviors observed in mania. Perceiving fear as merely surprise could lead manic persons to persist in approach behaviors, when withdrawal would be more adaptive. The negative correlation between recognition of sad faces and scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale suggests that the ability to perceive facial emotion may vary with the degree of mood disturbance.

Taken together, our findings are consistent with a positive bias in mania. Namely, we found deficits in recognizing the four negative emotions, no recognition errors for happy faces, and a tendency to mistake fear for the less negative emotion of surprise. However, manic subjects did not uniformly mistake negative emotions for positive emotions. To our knowledge, positive bias in mania has been described only once before, in an affective-shifting word task (8).

Fear recognition was unique in that the manic subjects performed the worst in this category, whereas the euthymic subjects with bipolar II disorder had better than normal performance. Hence, fear recognition may be preferentially affected in bipolar disorder and differentially affected across bipolar subtypes and mood states. Furthermore, the enhanced fear recognition in the euthymic bipolar II subjects suggests a distinctive pathophysiology for this illness subtype. Patients with bipolar II disorder may be more finely and accurately attuned to fearful expressions, which may contribute to heightened emotional reactivity and increased harm avoidance.

Further research on processing of social cues in bipolar disorder needs to include within-subjects designs to better address state versus trait phenomena, and it should be integrated with findings from functional imaging studies of the processing of facial emotion.

Received Jan. 23, 2001; revisions received May 1, May 25, and June 29, 2001; accepted Aug. 11, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lembke, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 401 Quarry Rd., Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305-5723; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported by NIMH grant MH-19938 and the APA/Lilly Psychiatric Research Fellowship.

Figure 1. Differences in Recognition of Facial Emotion Between Healthy Subjects and Manic Patients With Bipolar I Disorder or Euthymic Patients With Bipolar I or Bipolar II Disordera

aSignificant differences were determined with the Mann-Whitney U test, and the significance threshold was p≤0.025.

bEmotions besides fear and disgust included anger, sadness, surprise, and happiness.

cSignificantly different from healthy subjects (p<0.0005), euthymic subjects with bipolar I disorder (p=0.003), and euthymic subjects with bipolar II disorder (p<0.01).

dSignificantly different from healthy subjects (p=0.025) and euthymic subjects with bipolar II disorder (p=0.003).

eSignificantly different from healthy subjects (p=0.005) and euthymic subjects with bipolar I disorder (p<0.025).

fSignificantly different from manic subjects with bipolar I disorder (p=0.003) and euthymic subjects with bipolar I disorder (p=0.025).

1. David AS: Spatial and selective attention in the cerebral hemispheres in depression, mania, and schizophrenia. Brain Cogn 1993; 23:166-180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. George MS, Huggins T, McDermut W, Parekh PI, Rubinow D, Post RM: Abnormal facial emotion recognition in depression: serial testing in an ultra-rapid-cycling patient. Behav Modif 1998; 22:192-204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Vuilleumier P, Ghika-Schmid F, Bogousslavsky J, Assal G, Regli F: Persistent recurrence of hypomania and prosopoaffective agnosia in a patient with right thalamic infarct. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1998; 11:40-44Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ekman P, Friesen WV, O’Sullivan M, Diacoyanni-Tarlatzis I, Krause R, Pitcairn T, Scherer K, Chan A, Heider K, LeCompte WA, Ricci-Bitti PE, Tomita M, Tzavaras A: Universal and cultural differences in the judgments of facial expressions of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987; 53:712-717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ekman P, Friesen WV: Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976Google Scholar

7. Rubinow DR, Post RM: Impaired recognition of affect in facial expression in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 1992; 31:947-953Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Murphy FC, Sahakian BJ, Rubinsztein JS, Michael A, Rogers RD, Robbins TW, Paykel ES: Emotional bias and inhibitory control processes in mania and depression. Psychol Med 1999; 29:1307-1321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar