The Relationship of Borderline Personality Disorder to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic Events

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with respect to the role of trauma and its timing. METHOD: The Trauma History Questionnaire and the PTSD module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R were administered to 180 male and female outpatients with a diagnosis of one or more DSM-III-R personality disorders. Path analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between borderline personality disorder and PTSD. RESULTS: High rates of early and lifetime trauma were found for the subject group as a whole. Compared to subjects without borderline personality disorder, subjects with borderline personality disorder had significantly higher rates of childhood/adolescent physical abuse (52.8% versus 34.3%) and were twice as likely to develop PTSD. In the path analysis of the relationship between borderline personality disorder and PTSD, none of the different types of paths (direct path, indirect paths through adulthood traumas, paths sharing the antecedent of childhood abuse) was significant. The associations with both trauma and PTSD were not unique to borderline personality disorder; paranoid personality disorder subjects had an even higher rate of comorbid PTSD than subjects without paranoid personality disorder, as well as elevated rates of physical abuse and assault in childhood/adolescence and adulthood. CONCLUSIONS: The associations of personality disorder with early trauma and PTSD were evident, but modest, in borderline personality disorder and were not unique to this type of personality disorder. The results do not appear substantial or distinct enough to support singling out borderline personality disorder from the other personality disorders as a trauma-spectrum disorder or variant of PTSD.

Among the personality disorders, borderline personality disorder has been the most frequently studied in terms of the prevalence of early adverse events. Multiple studies have reported that a history of physical and sexual abuse in childhood has a high prevalence among patients with borderline personality disorder, with some studies finding that abuse is a nearly ubiquitous experience in the early lives of these patients (1–3). The high rate of early trauma in subjects with borderline personality disorder and the phenomenological overlap with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have led to the hypothesis that borderline personality disorder may be a trauma-related disorder or variant of PTSD stemming from early childhood trauma (1, 4). However, early trauma has not been systematically examined in subjects with other personality disorders, so it is unclear whether the association with early trauma is unique to borderline personality disorder.

High rates of comorbid PTSD, ranging from 26% to 57%, have been found in subjects with borderline personality disorder (5, 6). These findings further suggest that this particular personality disorder may be a variant of PTSD; however, it is not known how prevalent PTSD is in the other personality disorders. Several explanations have been proposed for the co-occurrence of borderline personality disorder and PTSD. The comorbidity could be the result of greater trauma exposure in patients with borderline personality disorder, either in childhood or later in life. Childhood trauma may be a focal precipitant to PTSD or may contribute to a cycle of revictimization that leads to trauma in adulthood (7, 8) and the subsequent development of PTSD. Subjects with borderline personality disorder may also be at greater risk for victimization or other forms of trauma later in life, perhaps as a result of their impulsivity or chaotic relationships, which could indirectly increase their risk of PTSD. Higher rates of PTSD in subjects with borderline personality disorder may also reflect a greater vulnerability to the psychological effects of traumatic stress (9) and a diminished ability to adapt to or recover from such events. The co-occurrence could also reflect an intrinsic link between the two disorders that is unrelated to trauma exposure, or the co-occurrence may simply be an artifact of overlapping diagnostic criteria, such as anger and dissociative symptoms. However, since the associations of borderline personality disorder with both childhood trauma and PTSD have not been studied concurrently, the relationship of these variables to one another and to traumatic events in adulthood is not known.

The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between borderline personality disorder and PTSD with respect to the role and timing of trauma exposure. These relationships were then examined among other types of personality disorders to determine whether associations with trauma and PTSD are unique to borderline personality disorder.

Method

We explored these associations in a large, carefully characterized group of outpatients with one or more personality disorders. We examined 1) whether borderline personality disorder is associated with physical abuse, sexual abuse, or other types of trauma in childhood/adolescence; 2) whether borderline personality disorder was associated with physical assault, sexual assault, or other forms of trauma in adulthood; and 3) whether the prevalence of PTSD was higher in subjects with borderline personality disorder. We used path analysis to examine a model of the relationship of borderline personality disorder and PTSD and their associations with trauma exposure in childhood/adolescence and adulthood. To examine whether the associations with trauma and PTSD were unique to borderline personality disorder, parallel analyses were performed for the other types of personality disorders.

All subjects provided written, informed consent after a complete description of the procedures. Subjects were recruited from clinics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and its affiliates and through advertisements and press releases. Subjects were included if they met the DSM-III-R criteria for at least one personality disorder. Subjects were excluded if they met the criteria for schizophrenia or another primary psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder (type I), substance dependence, a lifetime history of intravenous drug use, substance abuse within the previous 6 months, or a significant medical or neurological disorder. Major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder (type II) were not exclusionary diagnoses.

Subjects underwent diagnostic evaluation by a master’s-level psychologist. PTSD diagnoses were made by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (10). For axis II disorders, the Structured Interview for DSM-III-R Personality, Revised (11), was used to interview the subject and, when possible, an informant close to the subject. The interrater reliability (kappa) was 0.81 for borderline personality disorder diagnoses and 0.68 for paranoid personality disorder diagnoses.

The same evaluator obtained the subject’s trauma history using the Trauma History Questionnaire (12). This inventory was based on the high-magnitude stressor questionnaire used in the DSM-IV field trials and was designed to cover a broad range of events that could be considered potentially traumatic, including those related to crime, general trauma, and physical and sexual assault. Subjects were asked whether they had experienced each of 23 types of events and, if so, to provide additional information about the event, including the number of times it occurred, their ages when it occurred, and its emotional impact.

The Trauma History Questionnaire has been shown to have good test-retest stability (12), and comparative data are available from other groups of subjects (13, 14). No final scoring system is currently available for this instrument. To reduce the total number of items, the individual items were combined into the following nine categories, based on a modification of Green’s scoring system: 1) crime (had ever been robbed, had something taken by force, had a break-in when the subject was present, or had a break-in when the subject was absent), 2) accident/injury (had ever been in a serious accident, been seriously injured, or in another situation in which the subject feared that he or she would be seriously injured or killed), 3) combat (had ever engaged in military combat), 4) disasters (had ever been exposed to a natural disaster, a man-made disaster, or dangerous chemicals or toxins), 5) serious illness (had ever had a serious or life-threatening illness), 6) physical abuse/assault (had ever been attacked with a weapon or without a weapon or been punished or beaten to the point of injury), 7) sexual abuse/assault (had forced [anal, oral, or vaginal] intercourse, had been touched sexually under the threat of force), 8) witnessing violence or death (had ever seen someone seriously injured or killed, had seen or handled dead bodies [other than at a funeral]), and 9) bereavement (had a romantic partner or child who died, had a family member or close friend who was killed, or learned of serious injury of someone close).

Events that happened by the age of 18 were classified as occurring during childhood/adolescence, and those that happened after age 18 were classified as occurring in adulthood. This age cutoff allowed us to examine separately traumas that occurred before or around the time of development of the personality disorder, which by definition has its onset by late adolescence, from those that clearly occurred afterward.

Statistical Analysis

The associations of borderline personality disorder with the occurrence of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and each of the other seven types of trauma were examined by logistic regression analysis with gender controlled. The associations of borderline personality disorder with physical abuse/assault and with sexual abuse/assault were tested at a p level of 0.05, as the two tests reflected separate hypotheses based on previous findings of an association between borderline personality disorder and these specific types of events (1–3). For exploration of the associations between borderline personality disorder and other types of trauma, for which there were not specific hypotheses based on previous findings, the significance levels were adjusted to control for multiple comparisons. Since there were seven other trauma types, the associations were tested at a p level of 0.007 (0.05/7). Age was additionally used as a covariate in all analyses involving trauma in adulthood or PTSD. The adjusted odds ratio for developing PTSD was calculated for those with borderline personality disorder, with age and gender controlled. To evaluate further the specificity for borderline personality disorder, given the comorbidity among the axis II disorders, the analyses were repeated with all of the other personality disorders controlled. To examine whether the associations with trauma or PTSD were unique to borderline personality disorder, parallel analyses were performed for the other personality disorders.

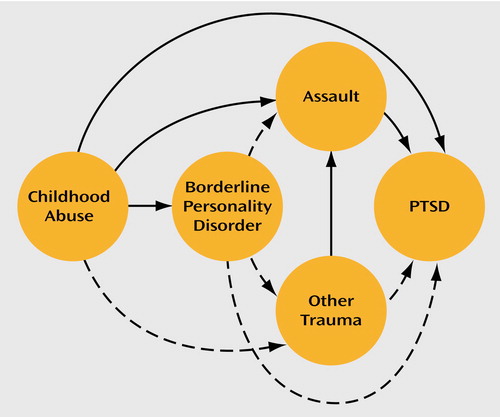

Path analysis (15) was used to evaluate the relationships among variables based on the model that childhood abuse, borderline personality disorder, assault and other traumas in adulthood, and PTSD occur in that order, as shown in Figure 1. For this analysis, physical abuse and sexual abuse in childhood/adolescence were combined into one predictor of borderline personality disorder on the basis of previous studies showing an association between the two (1–3). Physical and/or sexual assault in adulthood were also combined into one predictor and examined separately from other forms of trauma in adulthood, since a particularly strong association has been demonstrated between assaultive violence and PTSD (16, 17). It was not possible to make an a priori determination about which of the other measured trauma types to include in the “other” trauma category, since the literature on the association of PTSD with other specific traumas is not consistent. Instead, we chose the trauma types that showed a significant association with PTSD in this group of subjects; these types included exposure to disasters, combat, and accidents/injury. These trauma types have also been observed to be associated with a high probability of developing PTSD in other studies (17, 18).

In the path analysis, the correlation between borderline personality disorder and PTSD was decomposed into components for three types of paths: a direct path, indirect paths through assault and/or other traumas in adulthood, and paths involving the common antecedent cause of childhood abuse, which could be mediated through assault and or other traumas in adulthood (Figure 1). Three indirect paths—borderline personality disorder to assault to PTSD, borderline personality disorder to other trauma to PTSD, and borderline personality disorder to other trauma to assault to PTSD—were examined. Four paths with childhood abuse as a common antecedent were considered. In each, childhood abuse was directly linked to borderline personality disorder, but the association of childhood abuse to PTSD may have been through a direct path or through one of three indirect paths: childhood abuse to assault to PTSD, childhood abuse to other traumas to PTSD, and childhood abuse to other traumas to assault to PTSD. Each path’s component of the correlation is the product of the path coefficients that represent the direct effects between the pairs of variables in that path.

Results

Characteristics of the subjects

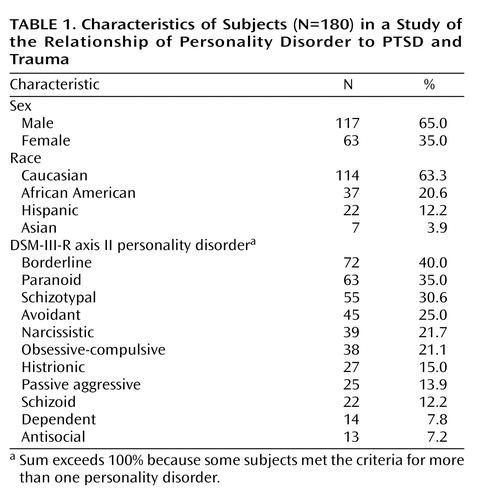

The study group consisted of 180 subjects ranging in age from 18 to 66 years, with a mean age of 37.0 years (SD=10.4). As Table 1 shows, the majority were male (65%) and Caucasian (63%). The most common axis II diagnoses were borderline, paranoid, and schizotypal personality disorder. The prevalence of borderline personality disorder in women (46.0%) and men (36.8%) did not differ significantly (χ2=1.47, df=1, p=0.22). Mean age did not differ between those with and without borderline personality disorder (mean=36.2 years, SD=10.5, versus mean=37.6 years, SD=10.4; t=0.85, df=178, p=0.40). Gender differences in types of trauma exposure were found. Men were more likely than women to report exposure to crime in childhood/adolescence (41.9% versus 23.8%; χ2=5.84, df=1, p=0.02). Women were more likely than men to report sexual abuse in childhood/adolescence (39.7% versus 14.5%; χ2=14.48, df=1, p<0.0005) and sexual assault in adulthood (25.4% versus 6.1%; χ2=13.8, df=1, p<0.0005). Therefore, gender was used as a covariate in all analyses comparing rates of trauma and PTSD.

Comorbidity among axis II diagnoses was common. Subjects met the criteria for an average of 2.4 personality disorder diagnoses (SD=1.6). The subjects with borderline personality disorder were more likely than those without borderline personality disorder to meet the criteria for histrionic (29.2% versus 5.6%; χ2=18.90, df=1, p<0.0005), narcissistic (30.6% versus 15.7%; χ2=5.59, df=1, p=0.02), and antisocial (12.5% versus 3.7%; χ2=4.98, df=1, p=0.03) personality disorder. Subjects with paranoid personality disorder were more likely than those without paranoid personality disorder to meet the criteria for schizotypal (49.2% versus 20.5%; χ2=15.89, df=1, p<0.0005), narcissistic (33.3% versus 15.4%; χ2=7.77, df=1, p=0.005), histrionic (23.5% versus 10.3%; χ2=5.90, df=1, p=0.02), and antisocial (12.7% versus 4.3%; χ2=4.34, df=1, p=0.03) personality disorder. Subjects with borderline personality disorder had a higher number of personality disorder diagnoses (other than borderline personality disorder) than subjects without borderline personality disorder (mean=2.3 diagnoses, SD=1.7, versus mean=1.8 diagnoses, SD=1.1; t=–2.35, df=178, p=0.02). Subjects with paranoid personality disorder also had a higher number of personality disorders (other than paranoid personality disorder) than subjects without paranoid personality disorder (mean=2.5 diagnoses, SD=1.7, versus mean=1.8 diagnoses, SD=1.1; t=–3.44, df=178, p=0.001).

Trauma in Childhood or Adolescence

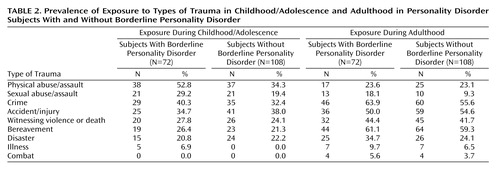

Table 2 shows the prevalence of exposure to trauma during childhood/adolescence in subjects with and without borderline personality disorder. Subjects with borderline personality disorder had significantly higher rates of physical abuse in childhood/adolescence than subjects without borderline personality disorder, with gender controlled (52.8% versus 34.3%; χ2=5.43, df=1, p=0.02), but the groups did not differ in their rates of sexual abuse (29.2% versus 19.4%; χ2=1.46, df=1, p=0.23) or of other types of trauma in childhood/adolescence.

Subjects with paranoid personality disorder also had a significantly higher rate of physical abuse in childhood/adolescence than subjects without paranoid personality disorder, with gender controlled (54.0% versus 35.0%; χ2=5.70, df=1, p=0.02). These groups did not differ in their rates of sexual abuse (25.4% versus 22.2%; χ2=0.23, df=1, p=0.63) or of other types of trauma in childhood/adolescence. The associations of childhood/adolescent physical abuse with borderline personality disorder and with paranoid personality disorder were also tested by using each of the other personality disorder diagnoses as additional covariates, and the results were statistically similar.

Subjects with antisocial personality disorder were more likely than those without antisocial personality disorder to have been bereaved in childhood (53.8% versus 21.0%; χ2=7.67, df=1, p=0.006). None of the other types of personality disorder was significantly and positively associated with sexual abuse, physical abuse, or any of the other types of trauma in childhood/adolescence.

Trauma in Adulthood

The rates of exposure to trauma in adulthood in subjects with and without borderline personality disorder are also shown in Table 2. Borderline personality disorder was not significantly associated with physical assault, sexual assault, or any other type of trauma in adulthood, with age and gender controlled. Subjects with paranoid personality disorder were significantly more likely than those without paranoid personality disorder to have experienced physical assault in adulthood, with age and gender controlled (33.0% versus 17.9%; χ2=4.84, df=1, p=0.03). Those with paranoid personality disorder also had higher rates of accidents/injury (63.5% versus 47.0%; χ2=4.86, df=1, p=0.03) and combat (9.5% versus 1.7%; χ2=6.48, df=1, p=0.01) than those without the disorder, but these differences were not statistically significant after the effects of multiple comparisons were controlled. None of the other types of personality disorder was significantly associated with any type of trauma in adulthood.

Prevalence of PTSD

The lifetime prevalence of PTSD in this group of subjects was 17.8% (N=32). The rates of PTSD in women (19.0%, N=12) and men (17.1%, N=20) were not significantly different (χ2=0.11, df=1, p=0.74). PTSD was most common in subjects with paranoid (29%) and borderline (25%) personality disorder, and least common in subjects with narcissistic (10%) and passive aggressive (12%) personality disorder. For the remaining types of personality disorder, the prevalence of PTSD ranged from 14% to 18%. Subjects with and without PTSD did not differ in their total number of personality disorder diagnoses (mean=2.5, SD=1.2, versus mean=2.4, SD=1.6; t=–0.36, df=178, p=0.72).

Subjects with borderline personality disorder had a significantly higher rate of PTSD than subjects without borderline personality disorder (25.0% versus 13.0%). The adjusted odds ratio was 2.20, with age and gender controlled (χ2=3.98, df=1, p<0.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01–4.80), and was 2.76 after the analysis additionally controlled for all of the other personality disorders (χ2=5.08, df=1, p=0.03, 95% CI=1.13–6.73). Subjects with paranoid personality disorder also had higher rates of PTSD than subjects without paranoid personality disorder (29% versus 12%). The adjusted odds ratio was 3.00, with age and gender controlled (χ2=7.59, df=1, p=0.006, 95% CI=1.37–6.59), and was 4.23 after the analysis additionally controlled for the other personality disorders (χ2=10.1, df=1, p=0.001, 95% CI=1.70–10.54). The odds ratios for the remaining personality disorders were not significant.

Path Analysis

Before the path analysis, preliminary analyses were done to determine whether there were substantial interactions with gender or race in the prediction of PTSD. These interactions were tested in stepwise linear regressions by using dummy-coded interaction variables. The overall tests of significance for the interaction with gender (F=1.78, df=4, 170, p=0.14) and with race (F=1.02, df=10, 162, p=0.43) were not significant. Therefore, the path analyses were conducted by using data for both genders and all races combined, and neither gender nor race was used as a predictor.

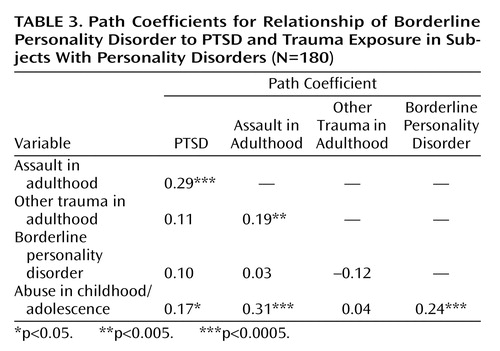

The causal directions of the associations between the trauma characteristics, borderline personality disorder, and PTSD in the model are shown in Figure 1, and the path coefficients are shown in Table 3. PTSD was significantly associated with childhood abuse and with assault in adulthood. Childhood abuse was also significantly associated with assault in adulthood and borderline personality disorder.

The simple correlation between borderline personality disorder and PTSD was statistically significant (r=0.15, df=178, p=0.04); however, the path coefficient for the direct path between borderline personality disorder and PTSD was small and not statistically significant (path coefficient=0.10, p=0.15). The sums of the components of the correlation for the indirect paths (path coefficient=–0.01) and the paths with the common antecedent of childhood abuse (path coefficient=0.06) were even smaller.

A parallel analysis was conducted for paranoid personality disorder, as shown Table 4. The simple correlation between paranoid personality disorder and PTSD was significant (r=0.21, df=178, p=0.005). The path coefficient for the direct path between paranoid personality disorder and PTSD was not significant (path coefficient=0.13, p=0.06). The sums of the components of the correlation for the indirect paths (path coefficient=0.05) and the paths with the common antecedent of childhood abuse (path coefficient=0.03) were even weaker.

Discussion

Childhood trauma was common in this group of patients with personality disorders: 41.7% reported a history of physical abuse, 26.3% reported a history of sexual abuse in childhood or adolescence, and the majority had sustained at least one traumatic event before age 18 years. Against this high base rate of early trauma, subjects with borderline personality disorder, as well as subjects with paranoid personality disorder, reported a significantly higher rate of physical abuse in childhood/adolescence. Although these data support the view that the rate of abuse is relatively increased in persons with borderline personality disorder, the discrepancies from the existing literature are also notable. Unlike most previous studies, this study found that subjects with borderline personality disorder did not report higher rates of sexual abuse in childhood/adolescence than comparison subjects without borderline personality disorder. Also, the observed rate of sexual abuse in childhood/adolescence of 29% in subjects with borderline personality disorder was lower than the rates of 46%–71% previously reported in such patients (1–3). Differences in subjects’ characteristics and in study methods may explain some of these discrepancies, as many of the subjects in previous studies were inpatients, and most were women. However, the present findings underscore the view that while sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence is common in the histories of persons with personality disorders, it is not invariably linked with borderline personality disorder nor is it a nearly universal occurrence in the lives of those who develop borderline personality disorder.

It has been hypothesized that subjects with borderline personality disorder might be at greater risk for victimization or exposure to other traumas owing to their characteristic impulsivity and instability. However, the data in the current study did not support this hypothesis. Subjects with borderline personality disorder were not more likely to be physically or sexually assaulted or to experience accidents, crimes, disasters, or other traumas in adulthood, compared with subjects with other personality disorders. Nonetheless, the overall group of subjects in this study was exposed to considerable trauma in adulthood. Indeed, their rates of adulthood traumas were higher than those described in a study of general psychiatric outpatients (13) that used the Trauma History Questionnaire, which in turn were considerably higher than those described in studies of nonpsychiatric subjects, e.g., women with breast cancer (14) and university students (13). However, even higher rates of childhood abuse and lifetime trauma have been described in persons with severe mental illness (16). These comparisons confirm the substantial association of lifetime trauma history with personality disorders and with mental illness generally.

Subjects with borderline personality disorder were twice as likely to develop PTSD as subjects without borderline personality disorder; however, this effect was modest. Indeed, the lower limit of the confidence interval for the odds ratio was 1.01. None of the three types of paths linking borderline personality disorder to PTSD—the direct path, the indirect paths through traumas in adulthood, and the paths involving the common antecedent of childhood abuse—was statistically significant. This finding partly reflects the relatively weak association between borderline personality disorder and PTSD in this group of subjects. Even though childhood abuse was significantly correlated with borderline personality disorder, assault in adulthood, and PTSD, these correlations were not large enough to make childhood abuse a significant common antecedent cause of these two disorders. Thus, no clear model emerged to explain the co-occurrence of borderline personality disorder and PTSD.

The links with trauma and PTSD were not unique to borderline personality disorder. Paranoid personality disorder was associated with physical abuse and assault in both childhood and adulthood and with an even higher rate of PTSD than was seen in subjects with borderline personality disorder. The association between trauma and paranoid personality disorder raises the possibility that these subjects’ mistrust and suspiciousness is rooted in early maltreatment, which may put them at even greater risk for subsequent victimization. In the path analysis, the association of paranoid personality disorder with PTSD through the direct path approached statistical significance, which could suggest some intrinsic link between the two disorders or could reflect overlapping diagnostic criteria, such as excessive vigilance. These findings are consistent with observations made in veterans, that paranoia before combat exposure predicts PTSD (18) and that paranoid personality disorder is common in veterans with PTSD (19).

The strongest predictors of PTSD were assault in adulthood and childhood abuse. These findings support the idea that childhood abuse is a risk factor for PTSD, irrespective of the type of personality disorder, and may be linked to PTSD by several mechanisms. In addition to directly precipitating PTSD, childhood abuse appears to increase the likelihood of later trauma exposures and may also increase the likelihood of developing symptoms after subsequent exposures (8, 20, 21).

One limitation of this study was that subjects’ trauma histories were based on retrospective reporting of events. As such, the histories cannot be taken as irrefutable accounts of personal history. Rather, they reflect individuals’ recall and disclosure of autobiographical events, which are influenced by many factors. However, if a bias for overreporting based on psychiatric status existed, it would apply to all subjects in this study group. On the other hand, the possibility that subjects with borderline or paranoid personality disorder or PTSD are more likely to recall or report episodes of trauma is not one that can be definitively excluded.

Borderline personality disorder was initially conceptualized as a mild form of schizophrenia, later as a variant of an affective disorder, and more recently as a variant of a traumatic stress disorder. The present findings of a relatively high rate of childhood physical abuse in persons with borderline personality disorder are largely consistent with the literature suggesting that trauma often precedes the development of borderline personality disorder. However, in light of these subjects’ high base rates of childhood trauma and PTSD, which were modestly and not uniquely associated with borderline personality disorder, the data do not support the idea that borderline personality disorder should be singled out from the other personality disorders as a trauma-spectrum disorder or variant of PTSD.

|

|

|

|

Received May 8, 2002; revision received Oct. 21, 2002; accepted March 17, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y.; and the Departments of Psychiatry and Biomathematical Sciences, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Golier, Bronx VAMC (116-A), 130 West Kingsbridge Rd., Bronx, NY 10468; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-5606 to Dr. Siever; Department of Veterans Affairs MERIT awards to Dr. Siever and Dr. Yehuda; a VA award to the Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; and NIH grant RR-00071 to Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Figure 1. Pathways Between Borderline Personality Disorder and PTSDa

aThe lines between circles designate pathways associated with path coefficients shown in Table 3. Solid lines designate significant path coefficients, and dashed lines designate nonsignificant path coefficients.

1. Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA: Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:490–495Link, Google Scholar

2. Zanarini MD, Gunderson JG, Marino MF, Schwartz EO, Frankenburg FR: Childhood experiences of borderline patients. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:18–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, Hill EM: Childhood sexual and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1008–1013Link, Google Scholar

4. Gunderson JG, Sabo AN: The phenomenological and conceptual interface between borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:19–27Link, Google Scholar

5. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V: Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1733–1739Link, Google Scholar

6. Hudziak JJ, Boffeli TJ, Kriesman JJ, Battaglia MM, Stanger C, Guze SB: Clinical study of the relation of borderline personality disorder to Briquet’s syndrome (hysteria), somatization disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and substance abuse disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1598–1606Link, Google Scholar

7. West CM, Williams LM, Siegel JA: Adult sexual revictimization among black women sexually abused in childhood: a prospective examination of serious consequences of abuse. Child Maltreat 2000; 5:49–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Nishith P, Mechanic MB, Resick PA: Prior interpersonal trauma: the contribution to current PTSD symptoms in female rape victims. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:20–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Siever LJ, Davis KL: A psychobiological perspective on personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1647–1658Link, Google Scholar

10. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M, Stangl D: Structured Interview for DSM-III-R Personality, Revised (SIDP-R). Iowa City, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, 1989Google Scholar

12. Green B: Psychometric review of Trauma History Questionnaire (self-report), in Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Edited by Stamm BH, Varra EM. Lutherville, Md, Sidran Press, 1996, pp 366–368Google Scholar

13. Green BL, Rowland JH, Krupnick JL, Epstein SA, Stockton P, Stern NM, Spertus IL, Steakley C: Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in women with breast cancer. Psychosomatics 1998; 39:102–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Meuser KT, Goodman BL, Trumbetta SL, Rosenberg SD, Osher FC, Vidaver R, Auciello P, Foy DW: Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:493–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pedhazur EJ: Structural equation models with observed variables: path analysis, in Multiple Regression in Behavioral Research: Explanations and Prediction, 3rd ed. Belmont, Calif, Wadsworth, 1997, pp 765–840Google Scholar

16. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schulz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Southwick SM, Yehuda R, Giller EL Jr: Personality disorders in treatment-seeking combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1020–1023Link, Google Scholar

19. Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Rosenberg SD: Premilitary MMPI scores as predictors of combat-related PTSD symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:479–483Link, Google Scholar

20. Resnick HS, Yehuda R, Pitman RK, Foy DW: Effect of previous trauma on acute plasma cortisol level following rape. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1675–1677Link, Google Scholar

21. Yehuda R, Halligan S, Grossman R: Childhood trauma and risk for PTSD: relationship to intergenerational effects of trauma, parental PTSD, and cortisol excretion. Dev Psychopathol 2001; 13:733–753Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar