PET Study of the Effects of Valproate on Dopamine D2 Receptors in Neuroleptic- and Mood-Stabilizer-Naive Patients With Nonpsychotic Mania

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A previous study reported a higher than normal density of dopamine D2 receptors in psychotic mania but not in nonpsychotic mania. The purpose of this study was to further examine D2 receptor density in a larger sample of nonpsychotic manic patients by using positron emission tomography (PET) and [11C]raclopride. METHOD: Thirteen neuroleptic- and mood- stabilizer-naive patients with DSM-IV mania without psychotic features and 14 healthy comparison subjects underwent [11C]raclopride PET scans. Of the 13 patients, 10 were treated with divalproex sodium monotherapy. PET scans were repeated 2–6 weeks after commencement of divalproex sodium. D2 receptor binding potential was calculated by using a ratio method with the cerebellum as the reference region. RESULTS: The [11C]raclopride D2 binding potential was not significantly different in manic patients than in the comparison subjects in the striatum. Treatment with divalproex sodium had no significant effect on the [11C]raclopride D2 binding potential in manic patients. There was no correlation between the D2 binding potential and manic symptoms before or after treatment. CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest that D2 receptor density is not altered in nonpsychotic mania and that divalproex sodium treatment does not affect D2 receptor availability.

Conventional neuroleptics such as haloperidol and chlorpromazine and novel antipsychotics such as olanzapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone are effective in treating acute mania (1–4); they all share the property of blocking dopamine D2 receptors. That the efficacy of neuroleptics in treating manic symptoms is related to their D2 receptors blockade is suggested by the observation that the cis isomer of flupentixol, which blocks D2 receptors, is effective in treating mania while the trans isomer of flupentixol, which does not block D2 receptors, is ineffective (5). Further support for this hypothesis also comes from reports suggesting a time course relationship between elevation in serum prolactin levels affected by D2 blockade and improvement in manic symptoms (6). Although other antimanic agents such as lithium and valproate do not block D2 receptors, there is evidence that lithium prevents D2 receptor supersensitivity induced by neuroleptics (7). It is currently unknown if valproate modulates D2 receptor density in humans and, in particular, in manic patients.

Functional brain imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can be used to measure D2 receptors in vivo in humans. Both PET and SPECT have been widely used to measure D2 receptors in acute schizophrenia (8–11). In contrast, to our knowledge, Pearlson and colleagues (12) are the only group to have measured D2 receptors in acute mania by using PET and [11C]N-methylspiperone. In that study, patients with psychotic mania and those with schizophrenia were noted to have a higher D2 receptor density compared with healthy volunteers, but D2 receptor density was no different in patients with nonpsychotic mania. The authors concluded that the higher density of D2 receptors was related to psychosis and not to manic symptoms. However, this study included only five nonpsychotic manic patients, and, of these, two had minimal symptoms at the time of scanning. Therefore, the question of whether nonpsychotic manic patients have a higher density of D2 receptors is unresolved. In this regard, it is important to note that D2 receptor blockers are effective in treating manic symptoms in both nonpsychotic and psychotic manic patients.

The purpose of this study was to measure D2 receptors in patients with acute nonpsychotic mania by using PET and [11C]raclopride.

To minimize the effects of confounding variables that affect D2 receptor density, we chose to measure D2 receptors in first-episode neuroleptic- and mood-stabilizer-naive manic patients and in healthy comparison subjects.

In addition, we examined the effects of valproate monotherapy on D2 receptors in manic patients, for two reasons: 1) valproate is an effective antimanic agent (13), but the mechanism by which it relieves manic symptoms is unknown; and 2) other effective antimanic mood stabilizers such as lithium have been shown to attenuate D2 receptor supersensitivity (14).

Method

Subjects

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of British Columbia, and both patients and healthy volunteers signed informed consent forms before participating in the study. Consecutive consenting patients (N=13) who met the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, manic episode without psychotic features (defined as the absence of delusions and hallucinations) were recruited. The diagnosis was based on all available clinical information, including the results of interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. All patients were neuroleptic- and mood-stabilizer-naive, and 11 of the 13 patients were experiencing their first manic episode. Those with other axis I diagnoses and comorbid drug or alcohol abuse within the past 6 months were excluded. All patients were assessed with the Young Mania Rating Scale (15) to measure the severity of symptoms.

Healthy volunteers matched for age and sex were recruited by advertisements. They had no history of drug or alcohol abuse, no personal history of psychiatric illness, and no family history of mood disorders or schizophrenia in first-degree relatives, as determined by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Non-Patient Edition. Both the patients and the comparison subjects were physically healthy, as determined by a medical history and a physical examination. All subjects had a magnetic resonance imaging scan to exclude any subject with gross brain pathology and for coregistration with PET images to facilitate localization of brain regions on PET images.

PET Scan Protocol

All subjects were free of psychotropic medication, except for lorazepam as needed for manic patients, for at least 2 weeks before the PET scans. A thermoplastic mask was molded to fit each subject’s head to minimize head movement, and the same mask was used for the repeat scan after treatment with divalproex sodium. Each subject had a 10-minute transmission scan to correct the PET data for attenuation. After this scan, each subject was given 140 MBq of [11C]raclopride as a bolus over a 1-minute period. Radioactivity in the brain was measured with the PET tomograph ECAT 953B/31 (CTI/Siemens, Knoxville, Tenn.). Scanning began 20 minutes after the injection of [11C]raclopride and continued for the next 40 minutes (a total of eight frames, each 5 minutes in duration). PET data were acquired in a three-dimensional mode and were represented in 31 image planes with 3.375-mm plane separation. The transaxial image resolution was 9 mm, and the axial was 6 mm.

In addition, the study subjects’ presynaptic dopamine function was assessed with [18F]6-fluoro-l-dopa PET scans. The results of the scans have been reported elsewhere (16).

Divalproex Sodium Treatment

After the PET scan, each patient began treatment with 500 mg of divalproex sodium b.i.d. Dose adjustments for divalproex sodium were made by the patients’ treating clinicians on the basis of clinical need, and, for all patients, serum valproic acid levels were in the therapeutic range at the time of the second scan. Patients were not allowed to receive any antipsychotics or any other psychotropic medication with the exception of benzodiazepines (lorazepam, temazepam, or oxazepam) for agitation and nighttime sedation. PET scans with [11C]raclopride were repeated 2–6 weeks after the start of divalproex sodium treatment.

Image Analysis

To reduce the effect of movement artifacts, the eight frames of the dynamic [11C]raclopride scans were realigned to frame 3 of the dynamic series by using the Automated Image Registration program (17). Frames 3–8 were summed together to create a mean image. A set of standard regions of interest was placed on the mean image on five separate planes centered on the striatum. The set of standard regions of interest consisted of four identical circular regions of 61.2 mm2 (diameter=8.8 mm) each, with one placed on the caudate and the other three on the putamen on each side of the striatum. The placement was determined by using a combination of visual markers and the location of maximum activity in the region. To correct for background activity, an oval-shaped reference region of interest of 2107 mm2 was placed on each side on three sequential planes of the cerebellum.

[11C]Raclopride D2 Receptor Binding Potential

An estimate of the D2 receptor binding potential (Bmax/Kd) was obtained by using a simple ratio method with the cerebellum as the reference region. Although this method tends to slightly overestimate the binding potential, it has been found to yield results that correlate well with estimates of binding potential made by using other methods (18).

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as means and standard deviations. To test the hypothesis that D2 receptor density was higher in the striatum of manic patients than in the healthy comparison subjects, [11C]raclopride D2 binding potential (hereafter referred to as D2 binding potential) in the two groups was compared by using an independent t test. The effect of divalproex sodium treatment on D2 binding potential in the striatum of the manic patients was examined by using a paired t test. Further exploratory post hoc analyses included the determination of the differences in D2 binding potential between manic patients and comparison subjects and within manic patients before and after treatment in the caudate, putamen, right striatum, and left striatum. These analyses used independent and paired t tests, as appropriate, with corrections for multiple comparisons. Pearson product-moment correlation was used to compute the correlation between D2 binding potential and manic symptoms as measured by the Young Mania Rating Scale.

Results

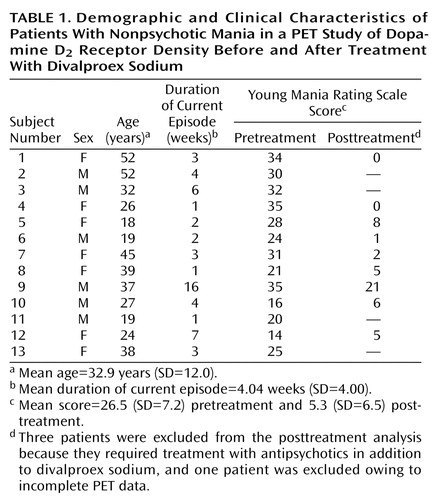

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The study subjects were 13 patients (seven women and six men) and 14 healthy comparison subjects (seven women and seven men). The mean ages of the study groups were 32.9 years (SD=12.0, range=18–52) for the patients and 30.9 years (SD=11.4, range=20–51) for the comparison group. There were no significant differences in age between the groups (t=0.44, df=25, p=0.66). The mean Young Mania Rating Scale score of the patients was 26.5 (SD=7.2) before treatment.

Of the 13 patients, three required treatment with antipsychotics in addition to valproate and hence were not scanned after treatment. The remaining 10 patients had posttreatment scans, and, of these, one patient was excluded from the pre-post comparison analysis because the field of view in the second PET scan did not include enough cerebellum area to calculate the binding potential. The Young Mania Rating Scale scores for the remaining nine patients decreased from a mean of 26.4 (SD=8.1) to 5.3 (SD=6.5) after 2–6 weeks of divalproex sodium treatment (t=–6.4, df=8, p=0.0001).

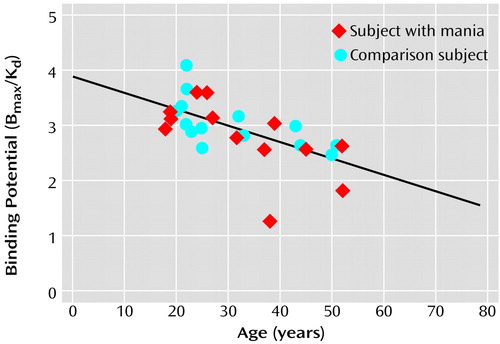

There was a significant negative correlation between D2 binding potential and age in study subjects (r=–0.62, df=26, p=0.001) (Figure 1) indicating that the D2 receptor density decreases with age in humans.

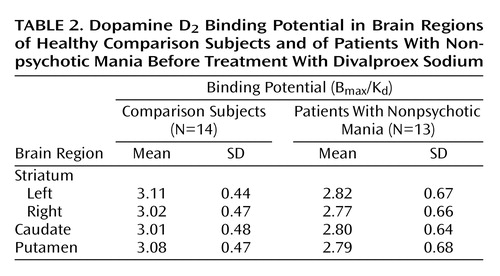

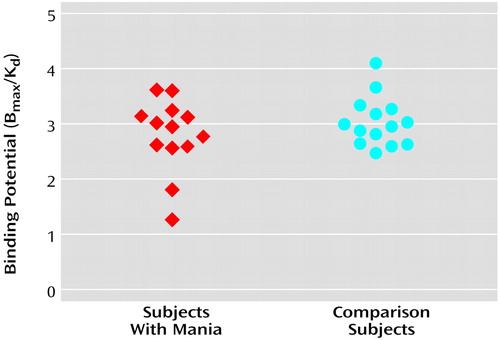

The D2 binding potential values in the striatum for the manic patients and the comparison subjects are presented in Figure 2. There was no significant difference in D2 binding potential in the striatum between manic patients (mean=2.79, SD=0.66) and healthy comparison subjects (mean=3.06, SD=0.44) (t=1.24, df=25, p=0.24). Similarly, no significant difference between the two groups in D2 binding potential was noted in the left or right striatum, the putamen, or the caudate (Table 2). There was also no correlation between D2 binding potential and Young Mania Rating Scale scores at baseline.

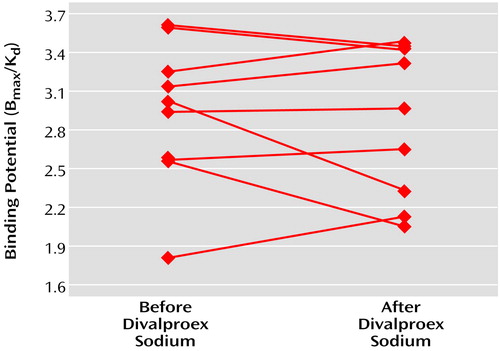

Treatment with divalproex sodium did not lead to any significant changes in D2 binding potential in manic patients in the striatum in the nine patients studied (pretreatment binding potential mean=2.95, SD=0.56; posttreatment binding potential mean=2.87, SD=0.59) (mean difference=0.08, SD=0.34) (95% confidence interval=–0.19 to 0.34; t=0.65, df=8, p=0.53) (Figure 3). Similarly, no treatment effect on D2 binding potential was noted in the caudate, putamen, right striatum, or left striatum (data not shown). There was a significant positive correlation between pre- and posttreatment D2 binding potential values in patients (r=0.83, df=8, p=0.006). There was, however, no correlation between D2 binding potential changes and changes in Young Mania Rating Scale scores.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate D2 receptor density in neuroleptic- and mood-stabilizer-naive, first-episode, nonpsychotic manic patients by using PET and [11C]raclopride. The results showed that the D2 binding potential was not higher in patients with nonpsychotic mania than in normal comparison subjects and, furthermore, that successful treatment with valproate did not alter D2 binding potential. There was also no correlation between D2 binding potential and manic symptoms as measured by Young Mania Rating Scale either at baseline or after treatment with divalproex sodium. There was a negative correlation between D2 binding potential and age in all study subjects.

One potential limitation of this study is that it used the ratio (basal ganglia/cerebellum) method to estimate D2 binding potential. Although the ratio method tends to overestimate D2 binding potential, results from this method have been previously found to correlate very well with the D2 binding potential estimated by using other methods, including the simplified reference tissue model (18–20). Furthermore, the ratio method has the same sensitivity as the other methods in detecting changes in D2 binding potential (18).

This study had several strengths. First, the study patients consisted of neuroleptic- and mood-stabilizer-naive patients, thus excluding the possibility of any confounding effects of previous treatment on D2 receptor density. Second, 11 of 13 patients were in their first manic episode, and we believe this minimized the possibility of effects of illness duration on D2 receptor density. Third, study patients were very closely matched with healthy comparison subjects for age and sex. This matching is important because previous studies have shown a correlation of sex and age with D2 receptor density (21–24). These previous findings were further confirmed in our study subjects. Fourth, we used [11C]raclopride to measure D2 receptors. This ligand has been widely accepted as suitable for measuring D2 receptors in psychiatric patients.

The results of this study suggest that dopamine D2 receptor density, as measured by D2 binding potential with [11C]raclopride, is not altered in manic patients without psychotic features. Several possible explanations for the negative findings must be considered. First, the possibility of type II error cannot be excluded, because of the small size of the study group. However, the D2 binding potential in the patients was numerically smaller than that in the comparison subjects. Furthermore, if the expected difference in D2 binding potential between the manic patients and the healthy comparison subjects was equal to the difference observed in this study, more than 60 subjects in each group would be required to prove an 80% chance of a significant difference between the groups if such a difference existed. Second, manic patients but not healthy comparison subjects in this study were allowed to receive lorazepam as needed, and one could argue that the effects of lorazepam on the dopaminergic system may have contributed to negative results. However, the findings from brain imaging studies of the effects of lorazepam on D2 receptors are conflicting. For instance, Dewey and colleagues (25) have shown that lorazepam increases D2 binding in baboons. They attributed this finding to the lorazepam-induced decrease in dopamine levels, which leaves more D2 receptors unoccupied for binding by raclopride. If such an effect had occurred in our study, it would have increased our chances of finding a higher level of D2 binding and, thus, could not explain the negative findings. Furthermore, in humans, treatment with lorazepam for 7 consecutive days had no effect on D2 binding as measured with raclopride and PET (26). A third possible explanation for the negative findings is suggested by previous work showing that changes in endogenous dopamine levels in synaptic space affect estimates of D2 receptor binding with raclopride (27, 28). For example, a higher level of D2 receptor density could be obscured by a similarly high level of endogenous dopamine in mania, thus resulting in estimates of normal levels of D2 receptor density in studies with raclopride. Such findings have been reported in raclopride-binding studies of schizophrenic patients, which showed no alteration in D2 receptors (8), although higher D2 receptor density and dopamine levels in the synaptic space have been detected by combining PET/SPECT with an alpha-methyl-paratyrosine depletion paradigm (29). Further studies combining PET and raclopride with alpha-methyl-paratyrosine challenge are needed to exclude this possibility.

The results of this study are consistent with the findings of Pearlson et al. (12), who reported no changes in D2 receptors in nonpsychotic manic patients. They used [11C]N-methylspiperone as a ligand, and previous studies have suggested that estimates of D2 receptor binding with [11C]N-methylspiperone are unaffected by endogenous dopamine levels. Taken together, the findings of our study and that of Pearlson et al. (12) indicate that D2 receptors are unaltered in acute nonpsychotic mania. However, we caution that this conclusion must remain tentative, given that raclopride-binding estimates are confounded by endogenous dopamine levels and that the study by Pearlson et al. included only two nonpsychotic manic patients with significant symptoms at the time of scanning.

Manic patients in this study had no change in D2 receptor density after improvement in symptoms after treatment with divalproex sodium. These results are consistent with a previous SPECT study that reported no differences in D2 receptors between euthymic bipolar disorder patients and healthy comparison subjects (30). If D2 receptor density in nonpsychotic manic patients is no higher than that in healthy comparison subjects and if treatment with valproate does not decrease D2 receptor density, how does one explain the efficacy of D2 receptor blockers such as neuroleptics in treating acute manic symptoms? One possibility is that acute manic symptoms are associated with an increase in dopamine transmission due to an increase in dopamine release from the presynaptic terminal. Neuroleptics may decrease dopamine transmission resulting from an increase in dopamine levels by blocking D2 receptors, whereas medications such as divalproex sodium and lithium may work by either dampening second messenger signaling pathways or decreasing dopamine synthesis. Some support for this hypothesis comes from the observation that treatment with divalproex sodium led to a significant decrease in the rate constant (Ki) for fluorodopa uptake in first-episode manic patients (16). Alternatively, nonpsychotic mania is not associated with any abnormality in dopaminergic transmission, but blockade of D2 receptors counters an abnormality in another neurotransmitter or second messenger signaling pathway, thus resulting in relief of symptoms.

In summary, the results of this study suggest that D2 receptor density is not altered in nonpsychotic mania and that treatment with valproate does not affect D2 receptor density. However, further studies combining PET with a neuropharmacological depletion paradigm (e.g., alpha-methyl-paratyrosine depletion) are needed to confirm these findings.

|

|

Received Nov. 7, 2001; revision received May 7, 2002; accepted May 10, 2002. From the Division of Mood Disorders, the Division of Neurology, and the TRIUMF positron emission tomography program, University of British Columbia; University of Nottingham, Nottingham, U.K.; and Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan. Address reprint requests to Dr. Yatham, Mood Disorders Clinical Research Unit, University of British Columbia, 2255 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 2A1; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Stanley Foundation, TRIUMF, and a Michael Smith Foundation Senior Scholar Award to Dr. Yatham.

Figure 1. Relationship Between Dopamine D2 Binding Potential in the Striatum and Age in 13 Patients With Nonpsychotic Mania Before Treatment With Divalproex Sodium and in 14 Healthy Comparison Subjectsa

ar=–0.62, df=26, p=0.001.

Figure 2. Dopamine D2 Binding Potential in the Striatum of 13 Patients With Nonpsychotic Mania Before Treatment With Divalproex Sodium and in 14 Healthy Comparison Subjects

Figure 3. Dopamine D2 Binding Potential in the Striatum of Nine Patients With Nonpsychotic Mania Before and After Treatment With Divalproex Sodium

1. Chou JC: Recent advances in treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:3-21Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702-709Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Yatham LN: Safety and efficacy of risperidone as combination therapy for the manic phase of bipolar disorder: preliminary findings of a randomized double blind study (RIS-INT-46) (abstract). Int J Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 3(suppl 1):S142Google Scholar

4. Keck PE Jr, Mendlwicz J, Calabrese JR, Fawcett J, Suppes T, Vestergaard PA, Carbonell C: A review of randomized, controlled clinical trials in acute mania. J Affect Disord 2000; 59(suppl 1):S31-S37Google Scholar

5. Nolen WA: Dopamine and mania: the effects of trans- and cis-clopenthixol in a double-blind pilot study. J Affect Disord 1983; 5:91-96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Cookson JC, Silverstone T, Rees L: Plasma prolactin and growth hormone levels in manic patients treated with pimozide. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140:274-279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pert A, Rosenblatt JE, Sivit C, Pert CB, Bunney WE Jr: Long-term treatment with lithium prevents the development of dopamine receptor supersensitivity. Science 1978; 201:171-173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Farde L, Wiesel FA, Stone-Elander S, Halldin C, Nordstrom AL, Hall H, Sedvall G: D2 dopamine receptors in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]raclopride. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:213-219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wong DF, Wagner HN, Tune LE, Dannals RF, Pearlson GD, Links JM, Tamminga CA, Broussolle EP, Ravert HT, Wilson AA: Positron emission tomography reveals elevated D2 dopamine receptors in drug-naive schizophrenics. Science 1986; 234:1558-1563Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, Gil R, D’Souza CD, Erdos J, McCance E, Rosenblatt W, Fingado C, Zoghbi SS, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Krystal JH, Charney DS, Innis RB: Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:9235-9240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, Carson RE, Kolachana BS, de Bartolomeis A, Weinberger DR, Weisenfeld N, Malhotra AK, Eckelman WC, Pickar D: Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:2569-2574Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Pearlson GD, Wong DF, Tune LE, Ross CA, Chase GA, Links JM, Dannals RF, Wilson AA, Ravert HT, Wagner HN Jr: In vivo D2 dopamine receptor density in psychotic and nonpsychotic patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:471-477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG (Depakote Mania Study Group): Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918-924; correction, 271:1830Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Waldmeier PC: Is there a common denominator for the antimanic effect of lithium and anticonvulsants? Pharmacopsychiatry 1987; 20:37-47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Yatham LN, Liddle PF, Shiah I-S, Lam RW, Ngan E, Scarrow G, Imperial M, Stoessl J, Sossi V, Ruth TJ: PET study of [18F]6-fluoro-l-dopa uptake in neuroleptic- and mood-stabilizer-naive first-episode nonpsychotic mania: effects of treatment with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:768-774Link, Google Scholar

17. Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC: Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1992; 16:620-633Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lammertsma AA, Bench CJ, Hume SP, Osman S, Gunn K, Brooks DJ, Frackowiak RS: Comparison of methods for analysis of clinical [11C]raclopride studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996; 16:42-52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Lammertsma AA, Hume SP: Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 1996; 4:153-158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sossi V, Holden JE, Chan G, Krzywinski M, Stoessl AJ, Ruth TJ: Analysis of four dopaminergic tracers kinetics using two different tissue input function methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000; 20:653-660Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Volkow ND, Gur RC, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Moberg PJ, Ding Y-S, Hitzemann R, Smith G, Logan J: Association between decline in brain dopamine activity with age and cognitive and motor impairment in healthy individuals. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:344-349Link, Google Scholar

22. Pohjalainen T, Rinne JO, Någren K, Syvälahti E, Hietala J: Sex differences in the striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in vivo. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:768-773Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Kaasinen V, Någren K, Hietala J, Farde L, Rinne JO: Sex differences in extrastriatal dopamine D2-like receptors in the human brain. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:308-311Link, Google Scholar

24. Inoue M, Suhara T, Sudo Y, Okubo Y, Yasuno F, Kishimoto T, Yoshikawa K, Tanada S: Age-related reduction of extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptor measured by PET. Life Sci 2001; 69:1079-1084Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Dewey SL, Smith GS, Logan J, Brodie JD, Yu DW, Ferrieri RA, King PT, MacGregor RR, Martin TP, Wolf AP: GABAergic inhibition of endogenous dopamine release measured in vivo with 11C-raclopride and positron emission tomography. J Neurosci 1992; 12:3773-3780Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hietala J, Kuoppamaki M, Nagren K, Lehikoinen P, Syvalahti E: Effects of lorazepam administration on striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in man—a positron emission tomography study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997; 132:361-365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, Rosenblatt W, Zea-Ponce Y, Zoghbi SS, Baldwin RM, Charney DS, Hoffer PB, Kung HF: SPECT imaging of striatal dopamine release after amphetamine challenge. J Nucl Med 1995; 36:1182-1190Medline, Google Scholar

28. Carson RE, Breier A, de Bartolomeis A, Saunders RC, Su TP, Schmall B, Der MG, Pickar D, Eckelman WC: Quantification of amphetamine-induced changes in [11C]raclopride binding with continuous infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997; 17:437-447Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles LS, Weiss R, Cooper TB, Mann JJ, Van Heertum RL, Gorman JM, Laruelle M: From the cover: increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97:8104-8109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Anand A, Verhoeff P, Seneca N, Zoghbi SS, Seibyl JP, Charney DS, Innis RB: Brain SPECT imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in euthymic bipolar disorder patients. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1108-1114Link, Google Scholar