Diagnostic Orphans: Adolescents With Alcohol Symptoms Who Do Not Qualify for DSM-IV Abuse or Dependence Diagnoses

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Little is known about the validity of the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorders when applied to adolescents. This report describes a group of “diagnostic orphans,” adolescents with one or two DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptoms who do not meet the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence. METHOD: The study included 199 male and 173 female subjects aged 13–19 years. All subjects were regular drinkers, recruited from community sources and alcohol treatment programs. At baseline and at 1-year follow-up, DSM-IV alcohol use disorders were assessed with a version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, modified for DSM-IV criteria. RESULTS: Diagnostic orphans represented 31% of the drinkers without an alcohol use disorder. The orphans were similar to the alcohol abusers and dissimilar to the other drinkers in alcohol and substance use patterns and in the course of alcohol problems over 1 year. CONCLUSIONS: The results indicate limitations of the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorders when applied to adolescents. Diagnostic orphans should be considered separately from other drinkers in research and treatment efforts.

The diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders in DSM-IV were largely developed from research and clinical experience with adults (1), yet DSM-IV is often used when assessing, researching, and treating adolescent problem drinkers. Little is known about the validity of DSM-IV criteria when applied to adolescents. A valid taxonomic system is critical for advances in understanding the etiology, treatment, and prevention of alcohol problems among this age group (2) and for guiding the allocation of scarce health care resources. Clearly, there is a need for more research on how well current diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders apply to adolescents.

There are two primary alcohol use disorders in DSM-IV: alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse. For an alcohol dependence diagnosis, at least three of the following seven symptoms must be present within a 12-month period: tolerance; withdrawal symptoms or use of alcohol to avoid withdrawal symptoms; drinking for a longer period of time or in larger amounts than intended; unsuccessful attempts, or a persistent desire, to stop or control drinking; a great deal of time spent obtaining, using, or recovering from the effects of alcohol; important activities given up or reduced because of drinking; and continued alcohol use despite knowledge of having a physical or psychological problem that has been exacerbated or caused by alcohol.

A DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol abuse is given if criteria for alcohol dependence have not been met and at least one of four abuse symptoms is present. The four alcohol abuse symptoms are related to a pathological pattern of use and/or psychosocial consequences: recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, home, or school; recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (e.g., drunk driving); recurrent alcohol-related legal problems; and continued alcohol use despite knowledge of having a social or interpersonal problem that has been exacerbated or caused by alcohol.

The DSM-IV rule that dependence precludes an abuse diagnosis implies that in relation to dependence, alcohol abuse should be a relatively mild disorder with an earlier onset. This general view of alcohol disorders has been shared by many researchers (1). It follows that symptoms of abuse should tend to be mild and to have an early onset compared to symptoms of dependence. However, survival analyses of time to symptom onset among adolescents have suggested limitations of the DSM-IV categories of abuse and dependence symptoms. Martin et al. (3) found a first “stage” of adolescent alcohol problems characterized by two of the four abuse symptoms (role obligation problems and social-interpersonal problems) as well as three of the seven dependence symptoms (tolerance, drinking more or longer than intended, and much time spent using). These data suggest that some persons who are experiencing this first stage of alcohol problems can present with one or two dependence symptoms but no abuse symptoms.

Unlike DSM-III and DSM-III-R, in DSM-IV the abuse and dependence symptoms are mutually exclusive. Given the one-symptom threshold for abuse diagnoses and the three-symptom threshold for dependence diagnoses, individuals with one or two dependence symptoms but no abuse symptoms do not qualify for a DSM-IV alcohol use disorder. We coined the term “diagnostic orphans” to describe this group.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that diagnostic orphans are common among adolescents. Lewinsohn et al. (4) found that 13.5% of high school students were diagnostic orphans. Harrison et al. (5) reported that among those who had ever used alcohol or other drugs, 13% of ninth-graders and 9.9% of 12th-graders were diagnostic orphans. Diagnostic orphans also have been described in a household sample of adults (6).

The present research identified a group of diagnostic orphans and compared them to adolescents with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence and to other adolescent drinkers without an alcohol use disorder. External validators included alcohol and substance use, the presence of substance use disorders, and the course of alcohol problems over 1 year. We hypothesized that the diagnostic orphans would be similar to the subjects with alcohol abuse and dissimilar to the other drinkers without an alcohol use disorder. These results would be consistent with the view that diagnostic orphans have “fallen through the cracks” of the DSM-IV system for alcohol disorders.

METHOD

The 372 study subjects (199 male and 173 female), aged 13–19 years, participated in the assessment protocol of the Pittsburgh Adolescent Alcohol Research Center. The total study group was 76% Caucasian, 17.5% African American, and 6.5% with other ethnic backgrounds. The group represented a wide range of socioeconomic status. All subjects were regular drinkers, defined as consuming alcohol at least once per month for a minimum of 6 months. Approximately one-half of the group (N=185) was recruited from the general community through newspaper advertisements and random-digit dialing procedures, and about half (N=187) were from a variety of inpatient and outpatient alcohol and substance abuse treatment programs. The group had a broad range of alcohol-related problems, which was ideal for this study of adolescents with subdiagnostic DSM-IV alcohol symptoms.

Subjects participated in a day-long assessment protocol that measured alcohol and drug use and problems, as well as areas such as psychosocial functioning and comorbid psychopathology. Written informed consent was obtained. Alcohol and substance use and problems also were assessed with the same measures in a 1-year follow-up. The protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Biomedical Institutional Review Board.

Socioeconomic status was measured with the Hollingshead scale (7). Lifetime patterns of alcohol and drug use were assessed with a structured interview adapted from Skinner’s Lifetime Drinking History (8). Interviewers determined, for each year of the subject’s life, the average and maximum quantity and frequency of use of alcohol and seven other classes of drugs. Past-year alcohol use was also assessed with an alcohol consumption questionnaire—a multiple-choice questionnaire that assessed frequency and average quantity of alcohol use, maximum quantity of alcohol used, and frequency of this maximum quantity in the past year.

Alcohol and other substance use disorders were assessed with a modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), adapted for DSM-IV criteria (9). SCIDs were conducted by clinical assessors trained by the authors. Assessors gave each symptom a rating of 1 (absent), 2 (subclinical), or 3 (clinically present). For each symptom rated as clinically present, ages at onset and offset were recorded to the nearest month. The SCID was administered immediately after assessors conducted a detailed interview that documented patterns of alcohol and other drug use throughout the subject’s life.

Four additional problem domains were added to the SCID to explore areas of functioning not contained in DSM-IV but thought to be relevant to adolescents: blackouts, passing out, craving, and alcohol-related risky sexual behavior. Each problem domain was defined by “continued alcohol use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent clinically significant problem with (domain) that is caused or exacerbated by the use of alcohol.” Exploratory problem domains were given detailed operational definitions consistent with other DSM-IV symptoms. We have reported preliminary data suggesting moderate to high levels of interrater reliability for DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses and symptoms among raters using our adapted SCID (9).

Subjects were placed into four groups on the basis of current DSM-IV diagnostic status: those with alcohol dependence, those with alcohol abuse, diagnostic orphans, and other drinkers with no alcohol diagnosis. In the statistical analysis, these four groups were first compared on demographic variables. Next, the four groups were contrasted on a series of validation variables that reflected alcohol and other substance use as well as problems associated with substance use. Analyses began with an overall one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) across the four groups. However, our main interest was in two planned comparisons that were made when significant main effects were obtained: comparing orphans to other drinkers without a diagnosis and comparing diagnostic orphans to the alcohol abuse group. In addition, these planned comparisons were made separately for community and clinical recruits. Finally, alcohol abusers, diagnostic orphans, and other drinkers were compared on the course of alcohol problems over 1 year. We predicted that the diagnostic orphans would show significantly greater alcohol and substance use and problems compared to the other drinkers and that these variables would tend not to distinguish the diagnostic orphans and the alcohol abusers. That is, we tested whether the diagnostic orphans, who did not have an alcohol use disorder, were more similar to a group with a diagnosis (alcohol abusers) than to other drinkers without a diagnosis. Data from the alcohol dependence group, expected to show the highest levels of alcohol and substance use and problems, are presented for the purpose of descriptive comparison.

RESULTS

Of the 372 adolescent drinkers, 135 received a current DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence, 110 alcohol abuse, and 127 no alcohol diagnosis. Of the 127 drinkers with no alcohol diagnosis, 39 (31%) were diagnostic orphans, defined by one or two clinically present alcohol dependence symptoms. Among the orphans, the predominant dependence symptoms were tolerance (occurring in 41%), drinking more or longer than intended (33%), unsuccessful attempts to quit or cut down (26%), and much time spent using (21%). Diagnostic orphans came from both clinical (36%) and community (64%) recruitment sources.

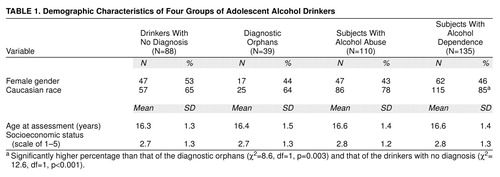

In the comparison of the four diagnostic groups on demographic variables, the groups did not differ in age at assessment, gender, or socioeconomic status (Table 1). Like the other groups, the diagnostic orphans had a fairly equal gender distribution. There was a significantly higher proportion of Caucasian subjects in the alcohol dependence group compared the orphans and the drinkers without a diagnosis. The diagnostic orphans did not differ in racial distribution from the other drinkers.

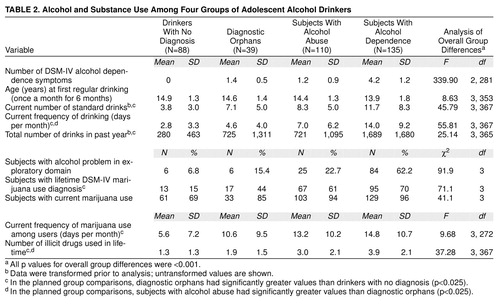

The four diagnostic groups were compared on a series of concurrent validation measures. Data from the SCID were used to determine the total number of DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptoms, the percentage of subjects who exhibited at least one alcohol problem in an exploratory domain, and the percentage of subjects with a cannabis use disorder (abuse or dependence). Alcohol use variables included the age at first regular drinking (at least once a month for at least 6 months), current average quantity and average frequency of drinking, taken from the structured Skinner interview (8), and an overall estimate of the number of drinks consumed in the past year, taken from the alcohol consumption questionnaire. Substance use variables included the percentage of current marijuana users, the frequency of marijuana use among these users, and the total number of illicit drugs ever used. The data are shown in Table 2.

The four diagnostic groups were compared on each of the concurrent validation measures with the use of ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square tests for percentage variables. Significant main effects were followed up by planned comparisons, contrasting diagnostic orphans with other drinkers without an alcohol diagnosis and orphans with alcohol abusers. These planned comparisons used an alpha level of 0.025 to reduce type I error. Data were log-transformed to achieve normality for two variables: total number of drinks consumed in the past year and current average number of drinks.

There was a significant overall main effect for all of the concurrent validation measures (Table 2). The total number of DSM-IV dependence symptoms is presented for descriptive purposes. Current average quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption and total number of standard drinks consumed in the past year were significantly higher among the diagnostic orphans than among the drinkers without a diagnosis. The orphans and alcohol abusers did not differ in the average quantity of alcohol consumed or in the total number of drinks consumed. However, the abusers did have a significantly higher average frequency of alcohol consumption than the orphans. The percentages of subjects who received a clinical rating on at least one alcohol problem in an exploratory domain were not different between the orphans and the other drinkers or between the orphans and the alcohol abusers.

The percentage of subjects with lifetime DSM-IV cannabis abuse or dependence was significantly lower among the drinkers without a diagnosis than among the orphans, who in turn had a significantly lower percentage than the alcohol abuse group. The percentages of subjects who currently used marijuana did not show significant differences in the two planned comparisons. However, the frequency of marijuana use among users was greater among the orphans than among the other drinkers without a diagnosis, and it did not distinguish the orphans from the alcohol abusers. The number of illicit drugs ever used was lower for the drinkers without a diagnosis than for the orphans, and in turn the value for the orphans was significantly lower than for the alcohol abuse group.

The pattern of results from our planned comparisons was quite similar when data were analyzed separately for community and clinical recruits. Among the community recruits, diagnostic orphans (N=25), compared to other drinkers (N=72), had a higher average number of drinks per occasion (6.8 versus 3.6; t=10.5, df=95, p<0.005), a greater number of drinking occasions per month (4.5 versus 2.4; t=9.7, df=95, p<0.005), a greater number of drinks in the past year (465 versus 249; t=6.6, df=95, p<0.02), and a higher percentage with a lifetime marijuana disorder (36% versus 8%; χ2=10.9, df=1, p=0.001). The orphans and drinkers did not differ significantly in the percentage of current marijuana users and those with an alcohol problem in an exploratory domain, the average frequency of marijuana use, or the number of drugs ever used, but all of the means were in the expected direction. The 25 diagnostic orphans and 54 alcohol abusers from community sources did not differ in the average quantity and total amount of past-year drinking, the percentage of subjects with lifetime marijuana use disorders and alcohol problems in exploratory domains, or the frequency of marijuana use. Greater values for the abusers compared to the orphans approached significance for the percentage of current marijuana users (χ2=4.3, df=1, p<0.04) and the average frequency of drinking (t=4.4, df=77, p=0.04). The abusers reported a greater number of drugs ever used than did the orphans (2.3 versus 1.2; t=9.5, df=77, p<0.005). Among the clinical recruits, the 56 alcohol abusers and 14 diagnostic orphans did not differ on any of the concurrent validity variables. While statistical power was limited for these comparisons, all p values were greater than 0.28.

We conducted our planned comparisons on alcohol symptoms and diagnoses at 1-year follow-up, with data available for 83 (75%) of the 110 alcohol abusers, 33 (85%) of the 39 diagnostic orphans, and 65 (74%) of the 88 regular drinkers without a diagnosis. The percentage of subjects who developed new symptoms during the year appeared to be greater among the orphans (30%) than among the other drinkers (17%), but this difference was not significant. The difference in the percentages of subjects with an alcohol use disorder among the orphans (24%) and the other drinkers (9%) approached significance (χ2=4.0, df=1, p=0.045). None of the drinkers, and 6% of the orphans, developed alcohol dependence during the 1-year period. In contrast, the orphans and the abusers were very similar in the percentages who developed new symptoms (30% versus 33%). The percentage of subjects who developed a new alcohol diagnosis was 24% for the orphans and 17% for the abusers. However, this 17% of abusers developed alcohol dependence, compared to 6% of the orphans. None of these differences was significant.

DISCUSSION

Diagnostic orphans were defined conceptually as persons with one or more clinically present alcohol symptoms who did not have a DSM-IV alcohol use disorder. According to the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence, diagnostic orphans are those who have one or two dependence symptoms and no abuse symptoms. The alcohol and substance use patterns and substance problems of the diagnostic orphans tended to be similar to those of the subjects with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and significantly greater than those of the other drinkers without an alcohol diagnosis. The course of alcohol problems over 1 year was similar among the orphans and the abusers and was more severe in the orphans than in the other drinkers without a diagnosis.

We found that diagnostic orphans were common (31% of drinkers without a diagnosis) and included both male and female subjects, taken from both treatment and community sources of subject ascertainment. It is problematic that DSM-IV criteria produce a group without an alcohol diagnosis that is not readily distinguishable from a group of subjects with a diagnosis of alcohol abuse. Similar to the current findings, Hasin and Paykin (6) found that adult diagnostic orphans were intermediate between subjects with dependence and drinkers with no symptoms. Unfortunately, that study did not include the critical contrast of an alcohol abuse group.

Many believe that alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses should be developmental, such that abuse symptoms should be less severe than, and have an onset before, dependence symptoms. However, our data suggest that the emergence of certain dependence symptoms before any abuse symptoms is common. Specifically, diagnostic orphans tended to report dependence symptoms related to tolerance, using alcohol more or longer than intended, unsuccessful attempts to quit or cut down, and much time spent using. These data are consistent with results of survival analysis suggesting that in adolescents, the onset of three of these dependence symptoms occurs at a relatively early age (3). Those results, together with the current findings, suggest that diagnostic orphans may be presenting with symptoms from a first stage of alcohol problems, albeit without clinically present abuse symptoms.

The occurrence of diagnostic orphans suggests limitations of the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorders when applied to adolescents, particularly the criteria for alcohol abuse, with its one-symptom threshold from a criterion set that does not overlap with dependence symptoms. Other research suggests limitations of the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse among adults. Abuse diagnoses show low concordance across the iterations of DSM, suggesting very different approaches to definition (10). There is no accepted conceptual core for the abuse diagnosis, which has been described as a “category without content” (11).

Therefore, an important area for future research is to examine the validity of alternative definitions of alcohol abuse and/or dependence. One approach would be to define sets of abuse and dependence symptoms that are clearly distinguished in terms of severity and relative age at onset. Alternatively, the criterion sets for abuse and dependence could be combined, and abuse and dependence could be defined by different symptom thresholds (5). Another possibility is to examine the effects of changing the symptom threshold for alcohol abuse from one of four abuse symptoms to two of four abuse symptoms. This change would not give an alcohol abuse diagnosis to diagnostic orphans, but it would probably produce an alcohol abuse group with greater severity.

Caution is necessary in interpreting the current results because of a number of limitations. The baseline data were cross-sectional and based on retrospective reports of behavior, so data on alcohol use and associated problems involved an extended recall period in many cases. No corroborative information about diagnoses was collected from parents or peers. Also, equivalent numbers of subjects were recruited from treatment programs and community sources. Because the study group was not epidemiologically based and data are reported only for regular drinkers, the data should not be generalized to the adolescent population.

The current results have important implications for clinical interventions. Diagnostic orphans may be an important group for early case identification and intervention. Although these adolescents do not have a DSM-IV alcohol use disorder, they may be at high risk for developing alcohol and other substance use disorders in the future. Diagnostic orphans show alcohol and substance use patterns similar to those of alcohol abusers and may need current treatment as much as the abusers. It would be unfortunate if such treatment is less available because lack of an alcohol diagnosis prevents insurance coverage for treatment.

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Steamboat Springs, Colo., June 17–22, 1995, and at the 43rd annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Philadelphia, Oct. 22–27, 1996. Received April 16, 1998; revisions received Sept. 4 and Nov. 4, 1998; accepted Nov. 20, 1998. From the Pittsburgh Adolescent Alcohol Research Center, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Ms. Pollock, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213; pollocknk @msx.upmc.edu (e-mail). Supported by grants AA-08746 and AA-00249 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

|

|

1. Nathan P: Substance use disorders in the DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:356–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Robins L, Barrett J (eds): The Validity of Psychiatric Diagnosis. New York, Raven Press, 1989Google Scholar

3. Martin CS, Langenbucher JW, Kaczynski NA, Chung T: Staging in the onset of DSM-IV alcohol symptoms in adolescents: survival/hazard analyses. J Stud Alcohol 1996; 57:549–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR: Alcohol consumption in high school adolescents: frequency of use and dimensional structure of associated problems. Addiction 1996; 91:375–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ: DSM-IV substance use disorder criteria for adolescents: a critical examination based on a statewide school survey. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:486–492Link, Google Scholar

6. Hasin D, Paykin A: Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: diagnostic “orphans” in a community sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998; 50:19–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hollingshead AB: Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

8. Skinner H: Development and Validation of a Lifetime Alcohol Consumption Assessment Procedure: Substudy 1248. Toronto, Addiction Research Foundation, 1982Google Scholar

9. Martin CS, Kaczynski NA, Maisto SA, Bukstein OM, Moss HB: Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. J Stud Alcohol 1995; 56:672–680Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hasin D, Grant B, Cottler L, Blaine J, Towle L, Ustun B, Sartorius N: Nosological comparisons of alcohol and drug diagnoses: a multisite, multi-instrument international study. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997; 47:217–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Langenbucher J, Martin C: Alcohol abuse: adding content to category. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996; 20(suppl):270A–275AGoogle Scholar