DSM-IV Substance Use Disorder Criteria for Adolescents: A Critical Examination Based on a Statewide School Survey

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorders were incorporated into the 1995 Minnesota Student Survey in order to estimate the need for alcohol/drug treatment among adolescents in the state. This study used data from the survey to examine the utility of individual diagnostic criterion items, diagnostic categories, and diagnostic thresholds in a general adolescent population. METHOD: The survey was administered to ninth- and 12th-grade public school students. Participation was voluntary, and survey questionnaires were anonymous. The survey included questions about the use of substances during the past year and the presence of DSM-IV criterion symptoms for substance abuse and dependence. This study was based on responses from 74,008 students who answered these questions. RESULTS: Of the students who reported any substance use in the past 12 months, 13.8% of the ninth graders and 22.7% of the 12th graders met the criteria for a substance abuse diagnosis, and 8.2% of the ninth graders and 10.5% of the 12th graders met the criteria for dependence. The presence of multiple criterion symptoms was strongly associated with the use of multiple drugs. Analyses of positive and negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity did not support the diagnostic distinction between dependence criteria and abuse criteria. CONCLUSIONS: A combined set of criteria, with empirically derived diagnostic threshold categories based on total number of symptoms, may be more suitable for estimates of substance use disorders and need for treatment among adolescents.

National, state, and local surveys have provided a great deal of important information about trends in adolescent substance use (1–5). However, surveys of students typically do not elicit information about the substance use patterns and adverse consequences that constitute diagnostic criteria and are essential to estimates of the prevalence of substance use disorders.

In American society, the focus on the prevalence of any alcohol or other drug use among adolescents is understandable, since underage drinking is prohibited in most circumstances, and other psychoactive drug use is illegal regardless of age. In fact, with respect to adolescents, the term substance “use” has been largely abandoned in favor of substance “abuse,” reflecting the ideology that any use among minors constitutes abuse, since it violates the law. While defining any substance use as abuse serves the purpose of reflecting social disapprobation, it obscures the distinctions necessary to classify substance abuse and dependence as health problems. Diagnostic classifications are imperative for clear communication among researchers and clinicians (6), referral to appropriate clinical interventions and treatments (7, 8), and ensuring the accessibility of services dependent on third-party reimbursement (9). This last point is critical; if diagnostic criteria are overly inclusive, third-party payers may disallow the criteria for determining coverage (10).

While national epidemiological studies have incorporated diagnostic criteria to estimate the prevalence of substance use disorders among adults (11–13), comparable studies involving adolescents have not been conducted. Epidemiological studies are essential for ascertaining the level of treatment need among various populations and for establishing the natural history of dependence (14).

Although the DSM-IV criteria are helpful in organizing basic concepts common to the understanding of substance use disorders, epidemiological application of the criteria may be problematic, especially for adolescents. First, the imprecision of the individual criterion items in the DSM-IV framework makes it difficult to operationalize them into survey items. Terms such as “larger amounts,” “longer periods,” “persistent desire,” “recurrent use,” and “important activities” are not defined, so they are subject to different interpretations (15). Second, “tolerance” is a complex phenomenon, and there are large individual variations in the amounts of a substance that are needed to produce intoxication. Furthermore, an apparently reduced effect may result from behavioral rather than physiological adaptation to a substance (16–18). The concept of impaired control may also be problematic as it relates to adolescents. Many adolescents initiate substance use with out-of-control use; in fact, one of the most common reasons given for use by high school students is “to get high or smashed” (19). Finally, certain symptoms that are used as diagnostic criteria, such as substance-related physical problems and withdrawal syndromes, may take years to develop, limiting their applicability to adolescents. In addition, withdrawal is unique in that it is the only criterion which varies by substance, necessitating an extensive list of possible withdrawal signs and symptoms specific to each substance.

While the imprecision of particular criterion items presents a challenge to any epidemiological application of the DSM-IV framework, the framework itself is open to challenge along several lines. One critical limitation is its categorical nature. The arguments in favor of categorical versus dimensional diagnoses are described in detail elsewhere (20). Figure 1 illustrates the decision tree for determining a substance use disorder diagnosis according to DSM-IV. If three dependence criteria are met, a dependence diagnosis results. If one abuse criterion is met, an abuse diagnosis results. A diagnosis of dependence preempts a diagnosis of abuse. An anomaly arises from the fact that meeting one or two dependence criteria without meeting an abuse criterion results in no diagnosis. Particularly with regard to adolescents, one could raise a question about the benefit of any distinction with regard to abuse versus dependence. If the appropriate goal for adolescents is cessation of use, there may be no clinical utility for such a distinction.

Because the DSM-IV substance use disorder framework was developed on the basis of the manifestation of substance disorders in adults, its applicability to adolescents has not yet been ascertained (7, 17). Although it can be argued that the essential characteristics of a disorder should transcend age differences, there are examples in DSM-IV of differences in criteria based on age, such as those for conduct disorder in children and antisocial personality disorder in adults, and mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders (20). Age distinctions may be particularly important with respect to substance use disorders because of the incorporation of legal and social consequences into the criteria for a diagnosis of substance abuse. The same behavior that may elicit legal consequences for a minor (specifically, purchase of alcohol or alcohol consumption) is not subject to legal sanctions for an adult. Drinking may also cause disruptions in interpersonal relationships (with parents, for example) for a minor simply because alcohol consumption is prohibited. Thus, one would expect the threshold for adverse consequences associated with alcohol use to be much lower for adolescents than for adults, even if the amount of alcohol consumed or the circumstances of use were similar.

To estimate the extent of substance use disorders among adolescents and assess the unmet need for treatment services, the 1995 Minnesota Student Survey incorporated the DSM-IV substance use disorder diagnostic criteria. This survey of 79,398 public school students in grades 9 and 12 is believed to be the largest and most comprehensive epidemiological survey of substance use disorders among adolescents that has been conducted in the United States.

This comprehensive data set has the additional benefit of allowing for a critical examination of many issues related to substance use disorders. Thus, this report examines the following issues in an adolescent population: the prevalence of symptoms that constitute the DSM-IV substance dependence and abuse criteria, the prevalence of substance dependence and abuse diagnoses, the utility of individual DSM-IV criteria, and the applicability of the DSM-IV substance use disorder categorical framework.

METHOD

The Minnesota Student Survey was administered in 97% of the state's public school districts in 1995; 47,566 ninth graders (83% of enrollment) and 31,832 12th graders (57% of enrollment) participated in the survey. (High school seniors were less likely than ninth graders to be available for the survey because of the wide variety of off-campus alternatives available to them.)

Slightly fewer than 5% of the questionnaires were excluded from the database because the gender of the respondent was not given or there was a pattern of inconsistent or exaggerated responses. An additional 3.5% of ninth-grade and 1.9% of 12th-grade questionnaires were excluded from the study because the respondents did not complete the substance use section. The number of ninth- and 12th-grade student questionnaires available for data analysis was 74,008.

The Minnesota Student Survey is an anonymous, self-administered, paper-and-pencil questionnaire booklet completed in classrooms in the presence of school personnel. With very few exceptions, participating school districts used a passive consent procedure in which a letter was sent to parents or guardians describing the survey and stating that unless a parent or guardian notified the school that a child was not be included, the student would be asked to participate. At the time of survey administration, students were advised that their participation was voluntary; they could refuse to complete the survey, quit at any time, or skip any item.

The Minnesota Student Survey used the Monitoring the Future survey format (1) for questions about substance use in the past year. In addition, the survey incorporated 14 questions to represent DSM-IV substance use disorder criterion symptoms experienced in the previous 12 months. Because of the increased survey length necessary to incorporate withdrawal symptoms, and their presumed rarity among a school population, the withdrawal criterion was not included in the survey. Each criterion was inquired about globally, rather than being specifically related to each substance, because the repetition of criterion questions for nine substance categories would have resulted in an unacceptable increase in survey length. Furthermore, analyses based on adolescents admitted to treatment in Minnesota showed that an average of three substances was reportedly used in the 6 months before treatment, and 89.3% of adolescents reported the use of at least two substances (unpublished data).

For 11 of the 14 criterion items, the response choice was zero, one, two, or three or more times. For this study, the criterion threshold was set conservatively by selecting “three or more times” to define a recurrent or persistent pattern. For three items (tolerance, wanting to cut down, and impaired relationships), a yes/no response choice was used, as these were not deemed to constitute discrete events. Consistent with DSM-IV, a dependence diagnosis was defined as meeting the threshold for three of the six dependence criteria included in the survey. An abuse diagnosis was defined as meeting the threshold for one of the four abuse criteria, but not meeting the criteria for a diagnosis of dependence.

Positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated for all criterion items with respect to diagnoses of both abuse and dependence. Students who did not meet any of the criteria in the past 12 months were excluded from these analyses; while including users with no symptoms would have no effect on positive predictive value and sensitivity, their inclusion would severely restrict the range of negative predictive value and specificity.

RESULTS

Almost one-half (46.5%) of the 47,566 students in grade 9 and almost one-third (29.9%) of the 31,832 in grade 12 reported no use during the previous 12 months. Alcohol was by far the most commonly used substance by users in both grades, with marijuana ranking a distant second. Amphetamines and other people's prescription drugs were the next two most commonly used substances by users in both grades.

The prevalence of individual DSM-IV criterion items among substance users is presented in table 1. The most notable difference between grades was the much higher prevalence of physically hazardous use (specifically, driving after use) by older students. Two other criterion items were among the most commonly reported for both grades: tolerance and use despite social/interpersonal problems. Legal problems and giving up activities were the least commonly reported criterion items.

Users of multiple substances typically reported multiple criterion symptoms. Among the 6,873 students who reported three or more abuse or dependence criterion items, 12.0% reported the use of only one substance, 21.2% reported the use of two substances, and 66.8% reported the use of three or more substances (data not shown).

Table 2 presents the prevalence of substance use disorders among substance users on the basis of DSM-IV criteria. The majority of substance users in both grades did not report any criterion symptoms. In both grades, abuse diagnoses outnumbered dependence diagnoses, but the difference was greater for the older students. Although the prevalence of abuse diagnoses increased markedly from ninth to 12th grade, there was only a slight increase in the prevalence of dependence diagnoses. Of the students who met the criteria for a diagnosis of dependence, 79.2% of the 1,937 ninth graders and 91.2% of the 2,219 12th graders also met the criteria for a diagnosis of abuse; of the students who met at least one abuse criterion, 32.0% of the 4,787 ninth graders and 29.6% of the 6,812 12th graders also met the criteria for a dependence diagnosis (data not shown).

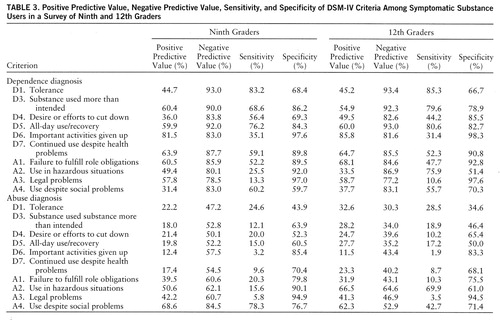

The utility of individual diagnostic criterion items is typically analyzed by calculating positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity. The likelihood of a disorder's presence and absence is given by the positive and negative predictive values, respectively, of criterion items (20), whereas the likelihood of a criterion symptom's presence and absence is given by the sensitivity and specificity, respectively. Table 3 presents the positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity for each criterion with respect to dependence and abuse diagnoses; analyses were limited to substance users who reported at least one criterion item of an abuse or dependence diagnosis.

Evaluating the positive predictive value of criteria in reference to substance use disorders is complicated by the fact that dependence and abuse diagnoses are not, by definition, mutually exclusive, and either diagnosis can include meeting criteria for the other. Typically, positive predictive value subtracted from 100% would yield the percentage of individuals who do not meet criteria for a diagnosis. However, for abuse criteria, meeting a single criterion results in one of two diagnoses: dependence, if it is combined with meeting at least three dependence criteria, or abuse, if it is combined with meeting one or two dependence criteria or if no dependence criteria are met. Therefore, the sum of the positive predictive value for a dependence diagnosis and the positive predictive value for an abuse diagnosis totals 100% for each abuse criterion. Although it is not apparent from table 3, the fact that dependence criterion symptoms can occur with a diagnosis of either dependence or abuse affects the positive predictive value for these criterion items as well. If a dependence criterion symptom is coupled with at least two other dependence criterion symptoms, this predicts a dependence diagnosis. If it is paired with just one other dependence criterion symptom, or is the sole dependence criterion symptom but is coupled with at least one abuse criterion symptom, this predicts a diagnosis of abuse.

Dependence Diagnosis

Giving up activities in order to use substances clearly stands above the rest of the dependence criteria for both age groups in terms of positive predictive value for a diagnosis of dependence. This criterion also had the highest rate of specificity for both grades. The next three highest items in terms of positive predictive value for dependence were use despite health problems, all-day use/recovery, and using more than intended. Tolerance and desire or efforts to cut down both failed to surpass 50% in positive predictive value. In fact, two abuse criteria (failure to fulfill role obligations and recurrent legal problems) exceeded these two dependence criteria in positive predictive value for dependence.

Tolerance, all-day use/recovery, and use more than intended were the criterion items highest in terms of sensitivity for a dependence diagnosis. The sensitivity rate of one abuse criterion, use despite social problems, exceeded the sensitivity rates of the remaining three dependence criteria. In addition, for 12th graders the sensitivity rate of the abuse criterion of hazardous use also exceeded the rates of the remaining dependence criterion items. One dependence criterion, giving up activities to use, had a very low sensitivity rate.

In these analyses, negative predictive value and specificity had much more restricted ranges than positive predictive value and sensitivity. In terms of rank order, however, the negative predictive value of the dependence criteria paralleled the sensitivity rates. The highest specificities for a dependence diagnosis among all the dependence and abuse criterion items were for giving up activities to use a substance and legal problems—one dependence criterion and one abuse criterion.

Abuse Diagnosis

Interpreting the utility of abuse criteria is impeded by the fact that approximately one-third of the students who met the criteria for an abuse diagnosis also met the criteria for a dependence diagnosis. With this limitation in mind, we offer a few comments. Only two abuse criterion items surpassed 50% in terms of positive predictive value for an abuse diagnosis: use despite social problems and hazardous use. Only one item, use despite social problems, exhibited high sensitivity for an abuse diagnosis for ninth graders; and only one item, use in hazardous situations, exhibited high sensitivity for 12th graders. Sensitivity for an abuse diagnosis was exceptionally low for legal problems among both ninth and 12th graders.

The negative predictive value of all the abuse criterion items was generally low for an abuse diagnosis with the exception of the use-despite-social-problems criterion for ninth graders. The criterion item with the highest negative predictive value for 12th graders was use in hazardous situations. Specificity for an abuse diagnosis in both grades was highest for legal problems. For ninth graders, the hazardous use criterion was also highly specific for an abuse diagnosis.

Co-occurrence of Criterion Symptoms

Because the analyses traditionally used to examine the relation between individual criterion items and diagnosis did not yield clearly interpretable results, we conducted a correlation analysis. Tetrachoric correlations (used for binary variables) between criterion items revealed that one criterion item, desire or efforts to cut down or quit, showed very weak correlations with all other items (they ranged from –0.19 to 0.16). In contrast, the other nine criterion items had correlations ranging from 0.23 to 0.66 with four to eight other criteria.

Since it was apparent from all the previous analyses that some symptoms were more likely than others to occur when there were with multiple symptoms, the mean number of abuse or dependence criterion items among symptomatic substance users was calculated for the combined group of ninth and 12th graders for the subset of individuals reporting each individual criterion symptom. The analysis presented in table 4 was developed as a mechanism to illustrate the likelihood of co-occurrence of criterion symptoms. Table 4 presents the 10 criterion items in ascending order of the mean number of other criterion items with which they co-occurred: desire or efforts to cut down (mean=2.47 other items), use despite social problems (mean=2.56 other items), tolerance (mean=2.71), use in hazardous situations (mean=2.74), substance used more than intended (mean=3.25), all-day use/recovery (mean=3.40), continued use despite health problems (mean=3.70), failure to fulfill role obligations (mean=4.34), legal problems (mean=4.73), and important activities given up (mean=4.92). This presentation allows an examination of the criterion distributions without the limitations imposed by the distinctions between abuse and dependence diagnoses and the different diagnostic thresholds.

In table 4 the row percentages (which total 100%) illustrate the frequency with which each criterion item occurred with no other criterion item, one other criterion item, two others, and so on. The three percentages that are in bold underline in the row for each criterion item constitute the highest-frequency cluster. For example, the first four criterion items were most likely to occur alone or with only one or two others. The final three criterion items were most likely to occur in combination with four to six others. The almost symmetrical pattern created by these clusters is striking. This pattern can be interpreted to mean that the 10 DSM-IV diagnostic criteria include an almost even balance of signs and symptoms that occur in the early, middle, and later stages of developing a substance use disorder.

DISCUSSION

This study was the first to evaluate the applicability of the DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorder in a large and representative general adolescent population. The Minnesota Student Survey demonstrated that sufficient information could be compiled from in-school survey responses to approximate diagnoses of substance use disorders. The decision to use generic rather than substance-specific diagnostic criterion items was supported by the findings, since the likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria increased with the use of multiple substances; almost nine out of 10 students who reported three or more diagnostic criterion symptoms used more than one substance. The advantage of this approach in terms of reducing the burden on respondents appears to outweigh any disadvantage in terms of substance-specific diagnoses. Similarly, the decision to omit withdrawal criteria probably did not affect the proportion who surpassed diagnostic thresholds; because a withdrawal syndrome is rare among adolescents (17, 21) and is a late-stage symptom of dependence (22), this criterion symptom would tend not to occur until other symptoms had accumulated.

Survey responses to criterion items appeared plausible, as evidenced by consistency with the findings in other studies. For example, physical health problems associated with substance use were found to be infrequent in adolescents in this survey and elsewhere (17). Similarly, we found that giving up activities in order to use substances was also relatively rare, a finding noted in other epidemiological research (16). Tolerance was found to have low specificity for a dependence diagnosis, which is also consistent with other studies (17, 21).

Some brief observations about specific criterion items are worth noting. The prevalence rate for eight criterion items was affected by using a minimum of three occurrences to meet the definition of a recurrent or persistent pattern. It could be argued that a lower threshold may be more desirable for potentially serious circumstances such as substance-related physical injuries and legal problems. One survey item—“Have you ever wanted to cut down on your use of alcohol or other drugs, or have you ever tried to cut down but couldn't?”—which was intended to measure impairment of control, clearly did not function as intended. Failure at attempts to stop or reduce use was intended to be the salient issue, but the first clause could elicit an affirmative response without such an indication. Another criterion item, hazardous use, showed a pronounced age-related effect, since driving under the influence was a prominent symptom only for older students.

Limitations of surveys include the nature of self-report data. However, earlier analyses of Minnesota Student Survey data suggest that survey responses are credible (23), and self-report inventories may have advantages over interviews in terms of reliability across data collection sites (20). The school survey method is also limited by the fact that adolescents with the most serious substance use problems may not be attending school. Evidence of this may be inferred from our finding that the prevalence of substance dependence did increase among 12th graders compared with ninth graders, as might be expected. For this reason, the Minnesota Student Survey was also administered in alternative education, correctional, and treatment settings; these populations will be the focus of future reports. Finally, the generalizability of findings based on adolescents in one north central state may be questioned. However, while regional differences in the prevalence of substance use have been found (1), so far there are no data to indicate that symptom patterns among heavy substance users vary by region.

The major finding with respect to DSM-IV criteria for adolescents was that the abuse/dependence diagnostic framework was not supported in this epidemiological study. The lack of evidence to support this diagnostic structure may have been due to problems with operationalizing the DSM-IV concepts for inclusion in a student survey, but this does not appear to be the case according to the intercorrelations among criterion items and the high percentage of dependence diagnoses that included abuse criterion items. The construct deficiency more likely resulted from the fact that the abuse/dependence distinction was developed on the basis of data and observations derived from limited populations: adults, individuals in clinical settings, and individuals with alcohol use disorders.

This study differed from previous investigations in three key aspects: the focus on adolescents, the use of a general population, and the inclusion of drugs other than alcohol. These differences are important because adolescents' patterns of use and the consequences they experience may differ from those of adults, in part as a direct result of their status as minors. Moreover, since clinical populations represent the more severe end of the spectrum of substance use problems and disorders (15), a different profile would be anticipated among a general population (15, 24). Finally, because the DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorders were derived primarily from the conceptualization of an alcohol dependence syndrome (25), the extent of pathological patterns of use or the accumulation of adverse consequences of use of drugs other than alcohol has not been adequately studied.

Although the abuse/dependence structure was not supported by the survey, combining the abuse and dependence criteria into a single set provided a meaningful illustration of the range of criterion profiles found in the student population and may offer increased utility. Of the 10 criterion symptoms included in the Minnesota Student Survey, four most frequently occurred alone or in combination with only one or two others, three occurred most often in combination with one to four others, and the remaining three occurred most often in combination with four to six others. This range may be important to retain because restricting the criterion set to only those items with high specificity for the diagnosis may actually compromise rather than enhance construct validity (20). These findings also suggest that a threshold of fewer than five criterion symptoms may be too low to define a substance use disorder for epidemiological estimates, because this threshold could be attained through criterion items that were among those with the lowest rates of positive predictive value and specificity relative to dependence. The possibility that the criterion threshold has been set too low for adolescents has been raised previously (21).

Because of the risks associated with substance use in adolescence and because any evidence of problematic use should heighten concern, an alternative diagnostic classification may prove to be more useful as a true measure of problem severity. For example, one or two symptoms could be identified as abuse, three or four symptoms as serious abuse or risk of dependence, and five or more symptoms as probable dependence. Such a continuum of problem severity may have greater utility for population-based assessments of the need for intervention and treatment services for adolescents. Future studies of the criteria for adolescent substance use disorder should include large and diverse general and clinical populations in order to further test this proposal.

|

|

|

|

Received March 13, 1997; revision received July 1, 1997; accepted Oct. 31, 1997. From the Minnesota Department of Human Services. Address reprint requests to Dr. Harrison, Minnesota Department of Human Services, Performance Measurement and Quality Improvement Division, 444 Lafayette Rd., St. Paul, MN 55155-3865; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by contract 270-94-0029 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and in part by the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment federal block grant. The authors thank Dan Bellandi for comments on this paper, Professional Data Analysts, Inc., for database preparation, the school personnel who administered the survey, and especially the participating students.

FIGURE 1. DSM-IV Substance Use Disorder Decision Tree

1 Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG: National Survey Results of Drug Use From the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975–1994, vol 1: Secondary School Students: NIH Publication 95-4026. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1995Google Scholar

2 Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K: Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory. J Stud Alcohol 1992; 53:447–457Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Oetting ER, Beauvais F: Adolescent drug use: findings of national and local surveys. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 58:385–394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1994: DHHS Publication 94-3063. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, 1994Google Scholar

5 Windle M: Alcohol use and abuse: some findings from the National Adolescent Student Health Survey. Alcohol Health Res World 1991; 15:5–10Google Scholar

6 Spitzer RL: Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Compr Psychiatry 1983; 24:399–411Google Scholar

7 Maisto SA, McKay JR: Diagnosis, in Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Treatment Handbook Series 4: NIH Publication 95-3745. Edited by Allen JP, Columbus M. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 1995Google Scholar

8 Nelson-Gray RO: DSM-IV: empirical guidelines from psychometrics. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:308–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Rinaldi RC, Steindler EM, Wilford BB, Goodwin D: Clarification and standardization of substance abuse terminology. JAMA 1988; 259:555–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Rounsaville BJ, Bryant K, Babor T, Kranzler H, Kadder R: Cross system agreement for substance use disorders: DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10. Addiction 1993; 88:337–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Pickering RP: Prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1992. Alcohol Health Res World 1994; 18:243–248Google Scholar

14 Caetano R: Two versions of dependence: DSM-III and the alcohol dependence syndrome. Drug Alcohol Depend 1985; 15:81–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Grant BF, Towle LH: A comparison of diagnostic criteria: DSM-III-R, proposed DSM-IV, and proposed ICD-10. Alcohol Health Res World 1991; 15:284–292Google Scholar

16 Grant BF, Chou SP, Pickering RP, Hasin DS: Empirical subtypes of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence: United States, 1988. Drug Alcohol Depend 1992; 30:75–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Martin CS, Kaczynski NA, Maisto SA, Bukstein OM, Moss HB: Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. J Stud Alcohol 1995; 56:672–680Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Rounsaville BJ, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Proposed changes in DSM-III substance use disorders: description and rationale. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:463–468Link, Google Scholar

19 Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ: Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse Negl 1997; 21:529–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Widiger TA, Trull TJ: Diagnosis and clinical assessment. Annu Rev Psychol 1991; 42:109–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Winters K, Stinchfield R, Fulkerson J, Henly G: Measuring alcohol and cannabis use disorders in an adolescent clinical sample. Psychol of Addictive Behaviors 1993; 7:185–196Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Martin CS, Langenbucher JW, Kaczynski NA, Chung T: Staging in the onset of DSM-IV alcohol symptoms in adolescents: survival/hazard analyses. J Stud Alcohol 1996; 57:549–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Harrison PA: Adolescent alcohol and drug problems: who is at risk? (University Microfilms number 9117615). Dissertation Abstracts International 1991; 52(1-B):518Google Scholar

24 Saunders JB, Conigrave KM: Early identification of alcohol problems. Can Med Assoc J 1990; 143:1060–1069Google Scholar

25 Edwards G, Gross MM: Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. Br J Addict 1976; 1:1058–1061Google Scholar