Temporal Dissociation Between Lithium-Induced Changes in Frontal Lobe myo-Inositol and Clinical Response in Manic-Depressive Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The most widely accepted hypothesis regarding the mechanism underlying lithium’s therapeutic efficacy in manic-depressive illness (bipolar affective disorder) is the inositol depletion hypothesis, which posits that lithium produces a lowering of myo-inositol in critical areas of the brain and the effect is therapeutic. Lithium’s effects on in vivo brain myo-inositol levels were investigated longitudinally in 12 adult depressed patients with manic-depressive illness. METHOD: Medication washout (minimum 2 weeks) and lithium administration were conducted in a blinded manner. Regional brain myo-inositol levels were measured by means of quantitative proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at three time points: at baseline and after acute (5–7 days) and chronic (3–4 weeks) lithium administration. RESULTS: Significant decreases (approximately 30%) in myo-inositol levels were observed in the right frontal lobe after short-term administration, and these decreases persisted with chronic treatment. The severity of depression measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale also decreased significantly over the study. CONCLUSIONS: This study demonstrates that lithium administration does reduce myo-inositol levels in the right frontal lobe of patients with manic-depressive illness. However, the acute myo-inositol reduction occurs at a time when the patient’s clinical state is clearly unchanged. Thus, the short-term reduction of myo-inositol per se is not associated with therapeutic response and does not support the inositol depletion hypothesis as originally posited. The hypothesis that a short-term lowering of myo-inositol results in a cascade of secondary signaling and gene expression changes in the CNS that are ultimately associated with lithium’s therapeutic efficacy is under investigation.

Manic-depressive illness (bipolar affective disorder) is a common, severe, chronic, and often life-threatening illness (1–3). The discovery of lithium’s efficacy as a mood-stabilizing agent revolutionized the treatment of patients with manic-depressive illness (1, 4, 5), but despite its role as one of psychiatry’s most important treatments, the cellular and molecular basis for lithium’s therapeutic effects remains to be fully elucidated (6, 7). It has also been increasingly recognized in recent years that, although lithium has had a remarkable beneficial effect on the lives of millions (5, 8), a significant percentage of patients respond inadequately (9–13). With the growing recognition that manic-depressive illness likely is a heterogeneous group of disorders, the importance of identifying predictors of differential treatment responsiveness or resistance has become increasingly appreciated. Although some important clinical leads have been identified (10, 11, 13), there is at present a dearth of knowledge about the biochemical factors associated with lithium responsiveness or resistance. Thus, there is a clear need to elucidate the genetic and/or biochemical mechanisms associated with response or resistance to lithium’s actions, not only to better identify patients likely to respond to lithium treatment but also to facilitate the development of new therapeutic agents.

There has been considerable interest in the role of signal transduction pathways, in particular the phosphoinositide system, as potential biochemical targets of lithium’s actions (5–7, 14). Activation of a variety of receptors in the CNS induces the activation of phospholipase C isozymes (15), which catalyze the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to two second messengers, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate stimulates the mobilization of intracellular Ca+2, while diacylglycerol activates protein kinase C. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate can be phosphorylated and sequentially dephosphorylated to myo-inositol. The ability of a cell to maintain sufficient supplies of myo-inositol is crucial to the resynthesis of the phosphoinositides and the maintenance and efficiency of signaling. Lithium, at therapeutically relevant concentrations, is an inhibitor of inositol monophosphatase and polyphosphate-1-phosphatase, which are involved in recycling inositol mono- and polyphosphates to myo-inositol (16, 17). Furthermore, since the mode of enzyme inhibition is uncompetitive, lithium’s effects have been postulated to be most pronounced in systems undergoing the highest rate of PIP2 hydrolysis (reviewed in references 18 and 19). Thus, Berridge and associates (20, 21) proposed the “inositol depletion hypothesis,” which posits that the therapeutic effects of lithium are mediated by a depletion of myo-inositol. Since several subtypes of adrenergic, cholinergic, serotonergic, and metabotropic glutamatergic receptors are coupled to PIP2 hydrolysis in the brain, the inositol depletion hypothesis, as initially proposed, offered an attractive explanation for lithium’s therapeutic efficacy in treating multiple aspects of manic-depressive illness (18–21).

However, although the preclinical studies in toto have tended to demonstrate lithium-induced alterations in receptor-mediated phosphoinositide turnover, numerous methodological questions have been raised (see excellent review by Jope and Williams [6]). In addition, the temporal dissociation between lithium’s direct inhibition of inositol-1-phosphatase and its delayed clinical effects has led to the proposal that inositol depletion per se may not be responsible for lithium’s therapeutic effects (7, 22). However, a large body of preclinical data suggests that some of the initial actions of lithium may occur with a reduction of myo-inositol (23–26); this lowering of myo-inositol may initiate a cascade of secondary changes at different levels of the signal transduction process and gene expression in the CNS, effects that are ultimately responsible for lithium’s therapeutic efficacy (6, 7, 22). Despite the attractiveness of this hypothesis, to our knowledge it has never been investigated in patients with manic-depressive illness. Thus, there is a clear need to determine whether lithium reduces the levels of myo-inositol in critical brain regions of individuals with manic-depressive illness and whether individual differences in susceptibility to lithium-induced CNS myo-inositol reductions are major factors in predicting therapeutic efficacy.

A variety of neuroimaging studies have begun to provide important clues to the neuroanatomical basis of manic-depressive illness, and several converging lines of evidence indicate that abnormalities in the frontal and temporal cortices may play a role in the pathophysiology of manic-depressive illness (27–35). Recent developments in magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) allow for the direct and noninvasive monitoring of brain neurochemistry. In this study we used MRS to quantitatively measure regional brain myo-inositol concentrations at baseline and throughout the course of lithium treatment of bipolar depressed patients. It should be pointed out that the “myo-inositol resonance” measured by proton MRS, while predominantly myo-inositol, also contains minor contributions from other neurochemicals, including glycine and inositol-1-phosphate. We acknowledge the potential confounds presented by the compounds glycine and inositol-1-phosphate. However, on the basis of literature findings (36, 37) and our own data (not shown), we believe these contribute only a minor component (<5%) to the total myo-inositol resonance. In the present study we investigated the hypothesis that lithium reduces the levels of myo-inositol in the critical brain regions implicated in this illness in individuals with manic-depressive illness. In addition, we sought to determine whether any potential reductions in myo-inositol per se are associated with lithium’s therapeutic effects.

METHOD

Subjects

Adult patients were eligible for this study if they gave written informed consent according to procedures approved by the institutional review board, met the diagnostic criteria for bipolar mood disorder, and the most recent episode had been depression. The diagnosis was determined by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (38). Patients were excluded if they met the diagnostic criteria for any other DSM-IV axis I disorder during the 2 years preceding the index episode. In addition, patients with psychoactive substance abuse or dependence within 1 year of the index episode were excluded (patients with episodic abuse related to manic-depressive illness were not excluded). Patients were also excluded from the study if they had renal disease, hepatic disease, or hematological disease, which put them at greater risk for side effects from lithium, or if they had any of the following, which put them at greater risk for side effects from the MRS procedure: cardiac pacemaker, brain surgery for an aneurysm, recent major surgery, a neurostimulator, or metal fragments in or near the eye or brain.

The effects of lithium on regional brain myo-inositol levels were investigated in 12 patients who met the preceding criteria. Their mean age was 36.3 years (range=22–56), and the group contained seven women and five men. Eleven of these patients had bipolar I disorder (history of major depression plus mania), and one had bipolar II disorder (history of major depression and hypomania). Upon admission the subjects were administered blinded research capsules four times per day, any previous medications were tapered off (through these capsules), and the patients underwent a drug washout period that was at least 14 days long (depending on the half-lives of the previous medications). On completion of the washout period, the patients’ symptoms were reassessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale by trained blinded raters. All patients remained depressed after the washout period (Hamilton depression scale score: mean=18.75, range=11–29). Each patient then underwent a baseline MRS scan (methods to be described) before the initiation of lithium treatment through research capsules. Lithium treatment was initiated, and the dose was adjusted to obtain a therapeutic plasma level (0.8–1.2 meq/liter) over the first week of treatment. Brain myo-inositol levels were measured in these inpatients at three different time points by means of quantitative proton (1H) MRS: at baseline and after acute (5–7 days) and chronic (3–4 weeks) lithium administration by blinded personnel. The Hamilton depression scale was also administered by blinded raters at each of the MRS scan time points. The patients were maintained on a standardized low-monoamine diet throughout the study.

MRS Protocol

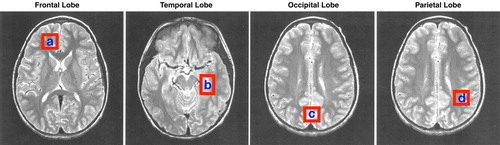

Quantitative single-voxel 1H MRS examinations were performed by using a 1.5-T clinical scanner (Signa/Horizon 5.6, General Electric, Milwaukee). A stimulated echo acquisition mode pulse sequence (39) was used to acquire spectra by means of the following acquisition variables and also included unsuppressed water reference scans for neurochemical quantitation: an echo time of 30 msec, a modulation time of 13.7 msec, a repetition time of 2 sec, an eight-step phase cycle, 2048 points, a spectral width of 2500 Hz, and 128 averages for a total acquisition time of approximately 5 minutes. Spectra were acquired from approximately 8-cc regions of interest in the right frontal, left temporal, central occipital, and left parietal lobes (Figure 1). Special care was taken to place the regions of interest in identical locations at the three time points (baseline, acute treatment, chronic treatment) by using a systematic approach that referenced voxel position to readily identifiable anatomical gyral landmarks within the brain.

Additional procedures were undertaken to evaluate the precision of the voxel placement from scan to scan in this longitudinal study and to control for potential partial-volume effects, which may potentially confound any MRS findings. We used a simple robust semiautomated image segmentation approach to determine the relative percentage of the various components, namely gray matter, white matter, and CSF, making up the voxel. Voxel content within each region of interest remained stable across the three time points; repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed there was no significant difference over time for gray matter, white matter, or CSF. Individual analysis of the combined data for voxel tissue content over time demonstrated that the voxel content was highly correlated and highly significant (df=59, p<0.0001) in all comparisons (baseline versus acute, r=0.96; baseline versus chronic, r=0.93; acute versus chronic, r=0.93).

Quantitative MRS Analysis

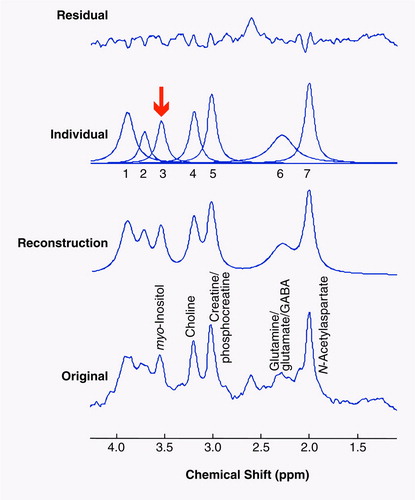

The compounds that were identified in the short-echo 1H MRS brain studies were N-acetylaspartate, glutamine/glutamate/γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), creatine/phosphocreatine, choline compounds, and myo-inositol. The area under each of the resonances is proportional to the concentration of the specific neurochemical compound. Individual peak areas were fit by using time-domain analysis software (40, 41), and the concentration of each compound was multiplied by 10,000. The result is reported as the ratio to brain water concentration (×104/water). This water-referencing method has been used in the field for over a decade and has been validated by a number of research groups (42–49). The analysis software is publicly available (http://carbon.uab.es/mruiwww) and eliminates much of the subjectivity previously involved in determining spectral peak areas.

Briefly, the software performs an automated fit of the unsuppressed water peak to determine its peak area and also uses the phase of the water peak to apply an automated zero-order phase correction to the metabolite data. After this, the user enters a priori information regarding the metabolite data in order to give the software starting values for its fitting process. The a priori information given includes the expected chemical shifts for each of the major chemical compounds appearing in the typical proton brain spectrum, as well as a starting line width determined by the corresponding water line width. The chemical shift values given to the program are based on literature values, which are 2.02 ppm for N-acetylaspartate, 2.30 ppm for the glutamine/glutamate/GABA complex, 3.03 ppm for creatine/phosphocreatine, 3.22 for choline compounds, and 3.56 for myo-inositol (50–54). With this input, the software then attempts to fit the metabolite spectrum and display its results both visually and in a file that can be pasted into a spreadsheet analysis program. In order to achieve reliable fits for myo-inositol, one must also fit the additional and partially overlapping peaks containing creatine/phosphocreatine and glutamine/glutamate/GABA in the immediate area of myo-inositol. (These are the peaks labeled 1 and 2 in figure 2, respectively.) The visual and quantitative results are inspected for goodness of fit and either accepted or reiterated again for improvement. Most of the spectra (approximately 80%) in this study required only one iteration apiece to achieve a satisfactory fit, with the majority of the others being successful after two iterations. The visual output of the program from a typical spectrum fit is shown in Figure 2. The analyzers are trained to accept a fit if the residual shows predominantly unstructured noise. The areas of the water peaks and neurochemical peaks are then entered into a spreadsheet, and the data for the individual neurochemical peaks are then multiplied by 10,000 (factor chosen for convenience in reporting data) and then divided by the unsuppressed brain water peak area (×104/water). We specifically did not attempt to correct for water and neurochemical relaxation effects with this technique, as obtaining these values on each of our patients would be prohibitively time consuming (measurement would take an additional 2 hours for each subject). We did, however, use acquisition variables that minimized the uncertainty in our neurochemical concentration estimates due to relaxation effects. Specifically, we used a short echo time, 30 msec, to minimize T2 signal decay and a standard repetition time of 2 seconds in order to minimize T1 error resulting from collection of spectra under less than fully relaxed conditions. This is a common tradeoff in clinical research studies.

Two research assistants (J.K.P. and M.W.F.) trained in nuclear magnetic resonance (MR) spectral analysis using this protocol evaluated the data in this study. The individuals were blind to the study information and to each other’s results. Intraclass correlation coefficient analysis revealed an interrater reliability of greater than 98% for in vivo quantitative measurement of brain myo-inositol concentration. We did not attempt to separate out the various minor components of the myo-inositol resonance, including inositol-1-phosphate and glycine. However, as discussed in the introduction, it is unlikely that these compounds contribute more than 5% of the myo-inositol resonance. The variability of our MRS measurement of brain myo-inositol (in normal volunteers) assessed at different time points has been described elsewhere (55) and is less than plus or minus 5%.

Data Analysis

Temporal changes in the myo-inositol concentrations were assessed by using within-subjects repeated measures ANOVA for each region of interest and time point separately. When there was violation of the sphericity assumption, the degrees of freedom were adjusted with the Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were used to identify significant differences between the scans at baseline, acute treatment, and chronic treatment. All reported p values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Of the 144 potential in vivo proton brain spectra (four brain regions at three time periods for each of the 12 subjects), 128 (89%) were available and judged to be of adequate quality to undergo quantitative analysis. Two subjects did not complete the scans during chronic treatment (loss of eight spectra), and eight other spectra were discarded because of poor quality due to inadequate water suppression, subject motion during the scan, or magnetic susceptibility artifacts.

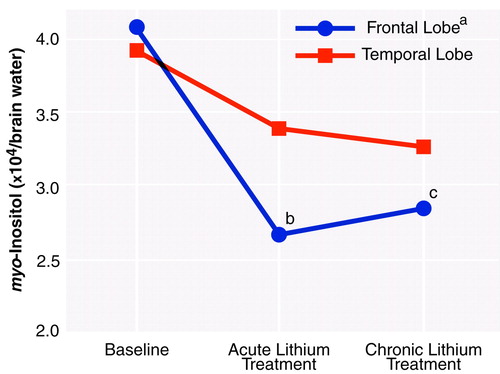

Figure 3 is a graph of the proton MRS measures of myo-inositol concentration at each time period for the frontal and temporal lobes. Overall, the myo-inositol concentration in the frontal lobe showed significant changes over time. Specifically, in the right frontal lobe the myo-inositol concentrations during both acute and chronic treatment were significantly lower than at baseline before we corrected for multiple comparisons. After correction, the two contrasts failed to reach the nominal level of significance. Although the temporal lobe data appeared to show a pattern somewhat similar to that for the frontal lobe, they failed to reach statistical significance. The temporal lobe data, however, had larger standard deviations, reflecting the difficulty in obtaining accurate measurements because of magnetic susceptibility artifacts from nearby sinuses and bone. No significant differences or trends were observed in the occipital and parietal lobes.

Because myo-inositol plays an important role in osmotic equilibrium, in addition to its role in the phosphoinositide signaling system, it may be possible that other neurochemicals are increasing as myo-inositol decreases. We did observe a change in another neurochemical measure within the frontal lobe region. Choline compounds showed a significant change in the frontal lobe over the course of lithium administration; however, the observed change was also a decrease. This observation has recently been presented in preliminary form (56); however, a complete discussion of this interesting finding is beyond the scope of this paper. There was no significant change or trend in the creatine/phosphocreatine concentration (commonly used as an internal MRS standard) in any of the brain regions investigated over the course of lithium administration.

Analysis of the scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at each of the time points corresponding to the MRS scans revealed a significant mean decrease (–36%) in the severity of depression over the course of the study (F=4.64, df=2, 18, p=0.02). The score during chronic lithium treatment was significantly lower than the score at baseline (t=3.58, df=9, p=0.006).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study we have shown for the first time, to our knowledge, that lithium treatment reduces myo-inositol levels in the right frontal lobe. The major effects were observed early in treatment and are consistent with lithium’s acute inhibition of inositol-1-phosphatase, which has been demonstrated in preclinical studies. However, the patients’ clinical state was clearly unchanged at this time, indicating that lowering of myo-inositol per se does not underlie lithium’s therapeutic effects. It is a heuristic working hypothesis that some of the initial actions of lithium may occur with a reduction of myo-inositol and that this reduction of myo-inositol initiates a cascade of secondary changes in the protein kinase C signaling pathway and gene expression in the CNS, effects that are ultimately responsible for lithium’s therapeutic efficacy (5, 6).

As discussed previously, the frontal lobe is one of the areas that has been implicated in the pathophysiology of this illness. Recent imaging and postmortem studies of this region (29–32) have documented both neuronal and glial cell abnormalities in subjects with familial manic-depressive illness. The frontal lobe region of interest used in this MRS study is larger than the areas examined in the imaging and postmortem studies and contains large proportions of both white and gray matter. However, it is interesting that the largest neurochemical changes we found are in this same general region. Although not as striking as the frontal lobe findings, the region of interest in the left temporal lobe (a brain region also implicated in manic-depressive illness) also showed similar overall effects; however, these failed to reach statistical significance. Because of the greater inherent variability of the data acquired from the temporal lobe region, a larger number of patients is needed to definitively determine whether there is indeed a reduction of myo-inositol in this region with lithium administration. In the two control brain regions (e.g., regions not strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of manic-depressive illness)—occipital and parietal lobes consisting predominantly of gray and white matter, respectively—we observed no significant changes or trends in myo-inositol levels during the course of lithium treatment, suggesting a local rather than “whole brain” phenomenon. Intriguingly, this finding is consistent with the uncompetitive nature of lithium’s inhibition of inositol-1-phosphatase (18–21), which suggests that the regions of the brain most affected by the pathophysiology of the illness are the most susceptible to lithium-induced myo-inositol changes. It has to be acknowledged, however, that the parietal and occipital lobes showed lower basal myo-inositol levels; thus, a role of “floor effects” in lithium’s regionally selective effects cannot be entirely ruled out. Although we observed changes in the 3.56-ppm region of the proton MR spectrum, which is entirely consistent with a lithium-induced lowering of the myo-inositol concentration, we again acknowledge that there may be minor contributions in this region of the spectrum from glycine and inositol-1-phosphate. However, any modest lithium-induced increases in inositol-1-phosphate in this peak that may be occurring suggest that we may, in fact, be underestimating the changes in myo-inositol levels.

We are aware of few previous studies in which lithium’s effects on CNS myo-inositol levels have been examined. Indirect CSF measures in one previous study (57) did not show any differences in CSF myo-inositol levels between lithium-treated patients and healthy comparison subjects; by contrast, another study (58) showed a lithium-induced reduction in CSF inositol monophosphatase activity. Given the regional brain differences in lithium’s effects that we found in our study, it is perhaps not altogether surprising that the indirect CSF studies have not revealed consistent findings. There is one other study in which lithium’s effects on CNS myo-inositol were examined by using MRS. Silverstone and associates (59) did not observe any significant effects of 7 days of lithium administration on myo-inositol levels in the temporal lobe of healthy volunteers. Silverstone et al. did not investigate lithium’s effects in the frontal lobe, and the study has a number of additional major methodological differences from our present study, including the use of myo-inositol/creatine ratios and healthy volunteers rather than patients with manic-depressive illness. Nevertheless, their results are consistent with the results of our present study.

Like investigators in previous studies (60–63), we found that even with a small study group, 4 weeks of lithium administration was associated with a significant reduction in Hamilton depression scale scores in our bipolar depressed patients. The authors of a comprehensive review of nine published studies (64) concluded that lithium is markedly more effective than placebo in the treatment of bipolar depression; however, those authors noted that the antidepressant effects demonstrated in the placebo-controlled studies often did not become evident until the third or fourth week of treatment. Given the now well-documented ability of antidepressants to precipitate manic episodes and to induce rapid cycling (65–69), lithium monotherapy, when possible, may indeed be the treatment of choice for bipolar depression for many (but not all) patients. Thus, delineating the biochemical processes underlying the ultimate responsiveness or resistance to lithium’s antidepressant effects is clearly a worthwhile endeavor. The observation that the administration of large doses of myo-inositol may have antidepressant efficacy in some patients (25, 70, 71) highlights the overall complexity of the system. The limited number of patients studied to date does not allow for comparison of differences between responders and nonresponders at this point. This, however, is clearly an interesting question worthy of further investigation in a larger study group.

In conclusion, a decrease in myo-inositol concentration with acute lithium administration in the right frontal lobe of patients with manic-depressive illness was clearly documented. Furthermore, lowering of myo-inositol levels per se did not appear to be associated with therapeutic efficacy. It remains a working hypothesis that the initial reduction of myo-inositol initiates a cascade of secondary changes in the protein kinase C signaling pathway and gene expression in the CNS, effects that are ultimately responsible for lithium’s therapeutic efficacy. Clearly, further study is warranted to delineate the role of lithium-induced reductions in regional brain myo-inositol levels and to determine whether, indeed, acute lithium-induced changes in brain myo-inositol concentration can predict an individual’s ultimate response or nonresponse to this agent.

Revised version of works presented at the 27th annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, New Orleans, Oct. 25–30, 1997, and the 53rd annual scientific convention of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, Toronto, May 27–31, 1998. Received Aug. 26, 1998; revisions received March 29 and May 10, 1999; accepted May 13, 1999. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Radiology, and Pharmacology and the Cellular and Clinical Neurobiology Program, Wayne State University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Moore, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine, UHC-9B, 4201 St. Antoine Blvd., Detroit, MI 48201; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by a Young Investigator grant to Dr. Moore from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and by grants from the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation, NIMH (MH-59107), and the State of Michigan (Joseph Young, Sr.) to Drs. Manji and Moore. The authors thank the nursing and research staff of the Neuropsychiatric Research Unit for their assistance and Caroline Zajac-Benitez, B.S., for editorial assistance.

FIGURE 1. Voxel Placement for Each Brain Region Investigated With Quantitative Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in 12 Patients With Bipolar Disorder

aRight frontal lobe.

bLeft temporal lobe.

cCentral occipital lobe.

dLeft parietal lobe.

FIGURE 2. Typical Proton Magnetic Resonance (MR) Spectrum for a Frontal Lobe Region in a Patient With Bipolar Disorder and Example of Quantitative Analysis Methoda

aThe bottom trace is the original proton MR spectrum. The spectral analysis software models the entire spectrum (next trace up) and then fits the individual peaks (next trace up). The uppermost trace in each panel shows the residual component that remains after the peak-fitting procedure is completed. Ideally, this should consist only of unstructured noise to achieve optimal quantitative results. The arrow indicates the position of the time domain fitted myo-inositol resonance.

FIGURE 3. Mean Brain myo-Inositol Concentrations at Baseline and After Acute (5–7 days) and Chronic (3–4 weeks) Lithium Treatment in Frontal and Temporal Lobe Regions in 12 Patients With Bipolar Disorder

aSignificant change over time (repeated measures ANOVA: F=5.62, df=1.172, 9.375, p=0.04).

bSignificant difference from baseline (uncorrected paired t test: t=2.46, df=8, p=0.04).

cSignificant difference from baseline (uncorrected paired t test: t=2.40, df=8, p=0.04).

1. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

2. Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER: The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:405–418Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wyatt RJ, Henter I: An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30:213–219Medline, Google Scholar

4. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L: Effects of lithium treatment and its discontinuation in bipolar disorder: overview of recent research findings from the International Consortium for Bipolar Disorders Research. Am Soc Clin Psychopharmacology Progress Notes 1997; 8(2):21–26Google Scholar

5. Manji HK, Lenox RH: Lithium: a molecular transducer of mood-stabilization in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19:161–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jope RS, Williams MB: Lithium and brain signal transduction systems. Biochem Pharmacol 1994; 77:429–441Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Manji HK, Potter WZ, Lenox RH: Signal transduction pathways: molecular targets for lithium’s actions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:531–543Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Chou JC: Recent advances in treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:3–21Medline, Google Scholar

9. Post RM, Ballenger JC, Uhde TW, Bunney WE Jr: Efficacy of carbamazepine in manic-depressive illness: implications for underlying mechanisms, in Neurobiology of Mood Disorders. Edited by Post RM, Ballenger JC. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1984, pp 777–816Google Scholar

10. Post RM, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, Kimbrell TA, Dunn RT: Beyond lithium in the treatment of bipolar illness. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19:206–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Manji HK, Chen G, Hsiao JK, Masana MI, Moore GJ, Potter WZ: Regulation of signal transduction pathways by mood-stabilizing agents, in Bipolar Medications: Mechanisms of Action. Edited by Manji HK, Bowden CL, Belmaker RH. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press (in press)Google Scholar

12. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG, Garzatrevino ES, Risch SC, Goodnick PJ, Morris DD: Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918–924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bowden CL: New concepts in mood stabilization: evidence for the effectiveness of valproate and lamotrigine. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19:194–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rana RS, Hokin LE: Role of phosphoinositides in transmembrane signaling. Physiol Rev 1990; 70:115–164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fisher SK, Heacock AM, Agranoff BW: Inositol lipids and signal transduction in the nervous system: an update. J Neurochem 1992; 58:18–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Allison JH, Stewart MA: Reduced brain inositol in lithium-treated rats. Nature New Biol 1971; 233:267–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hallcher LM, Sherman WR: The effects of lithium ion and other agents on the activity of myo-inositol-1-phosphatase from bovine brain. J Biol Chem 1980; 255:10896–10901Google Scholar

18. Nahorski SR, Ragan CI, Challiss RAJ: Lithium and the phosphoinositide cycle: an example of uncompetitive inhibition and its pharmacological consequences. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1991; 12:297–303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Atack JR, Broughton HB, Pollack SJ: Inositol monophosphatase—a putative target for Li+ in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Trends Neurosci 1995; 18:343–349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Berridge MJ, Downes CP, Hanley MR: Lithium amplifies agonist-dependent phosphatidylinositol responses in brain and salivary glands. Biochem J 1982; 206:587–595Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Berridge MJ, Irvine RF: Inositol phosphates and cell signalling. Nature 1989; 341:197–205Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Manji HK, Lenox RH: Lithium: a molecular transducer of mood-stabilization in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19:161–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Godfrey PP: Potentiation by lithium of CMP-phosphatidate formation in carbachol-stimulated rat cerebral-cortical slices and its reversal by myo-inositol. Biochem J 1989; 258:621–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Pontzer NJ, Crews FT: Desensitization of muscarinic stimulated hippocampal cell firing is related to phosphoinositide hydrolysis and inhibited by lithium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990; 253:921–929Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kofman O, Belmaker RH: Biochemical, behavioral and clinical studies of the role of inositol in lithium treatment and depression. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 34:839–852Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Tricklebank MD, Singh L, Jackson A, Oles RJ: Evidence that a proconvulsant action of lithium is mediated by inhibition of myo-inositol phosphatase in mouse brain. Brain Res 1991; 558:145–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ketter TA, George MS, Kimbrell TA, Willis MW, Benson BE, Post RM: Neuroanatomical models and brain-imaging studies, in Bipolar Disorder: Biological Models and Their Clinical Application. Edited by Young LT, Joffe RT. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1997, pp 179–217Google Scholar

28. Soares JC, Krishnan KR, Keshavan MS: Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: new insights into the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Depression 1996; 4:14–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR Jr, Todd RD, Reich T, Vannier M, Raichle ME: Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature 1997; 386:824–827Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Drevets WC, Ongur D, Price JL: Neuroimaging abnormalities in the subgenual prefrontal cortex: implications for the pathophysiology of familial mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry 1998; 3:190–191, 220–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Ongur D, Drevets WC, Price JL: Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95:13290–13295Google Scholar

32. Rajakowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Wei J, Dilley G, Pittman SD, Meltzer HY, Overholser JC, Roth BL, Stockmeier CA: Morphometric evidence for neuronal and glial prefrontal cell pathology in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:1085–1098Google Scholar

33. Devous MD, Rush AJ, Schlesser MA: Single-photon tomographic determination of regional cerebral blood flow in psychiatric disorders (abstract). J Nucl Med 1984; 25:P57Google Scholar

34. Altshuler LL, Conrad A, Hauser P, Li XM, Guze BH, Denikoff K, Tourtellotte W, Post R: Reduction of temporal lobe volume in bipolar disorder: a preliminary report of magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:482–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Swayze VW II, Andreasen NC, Alliger RJ, Ehrhardt JC, Yuh WT: Structural brain abnormalities in bipolar affective disorder: ventricular enlargement and focal signal hyperintensities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1054–1059Google Scholar

36. Ross BD: Biochemical considerations in 1H spectroscopy: glutamate and glutamine; myo-inositol and related metabolites. NMR Biomed 1991; 4:59–63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Shonk T, Ross BD: Role of increased cerebral myo-inositol in the dementia of Down syndrome. Magn Reson Med 1995; 33:858–861Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

39. Frahm J, Merboldt KD, Hanicke W: Localized proton spectroscopy using stimulated echoes. J Magn Reson 1987; 72:502–508Google Scholar

40. van den Boogaart A, Ala-Korpela M, Jokisaari J, Griffiths JR: Time and frequency domain analysis of NMR data compared: an application to 1D 1H spectra of lipoproteins. Magn Reson Med 1994; 31:347–358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. deBeer R, van den Boogaart A, van Ormondt D, Pijnappel WW, den Hollander JA, Marien AJ, Luyten PR: Application of time-domain fitting in the quantification of in vivo 1H spectroscopic imaging data sets. NMR Biomed 1992; 5:171–178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Thulborn KR, Ackerman JJH: Absolute molar concentrations by NMR in inhomogenous B1: a scheme for analysis of in vivo metabolites. J Magn Reson 1983; 55:357–371Google Scholar

43. Soher BJ, Hurd RE, Sailasuta N, Barker PB: Quantitation of automated single-voxel proton MRS using cerebral water as an internal reference. Magn Reson Med 1996; 36:335–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Christiansen P, Henriksen O, Stubgaard M, Gideon P, Larsson H: In vivo quantification of brain metabolites by 1H-MRS using water as an internal standard. Magn Reson Imaging 1993; 11:107–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Hetherington HP, Pan JW, Mason GF, Adams D, Vaughn MJ, Twieg DB, Pohost GM: Quantitative 1H spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 4.1 T using image segmentation. Magn Reson Med 1996; 36:21–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Frahm J, Michaelis T, Merboldt KD, Bruhn H, Gyngell ML, Hanicke W: Improvements in localized 1H NMR spectroscopy of human brain: water suppression, short echo times and 1 ml resolution. J Magn Reson 1990; 90:464–473Google Scholar

47. Klose U: In vivo proton spectroscopy in presence of eddy currents. Magn Reson Med 1990; 14:26–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Hennig J, Pfister H, Ernst T, Ott D: Direct absolute quantification of metabolites in the human brain with in vivo localized proton spectroscopy. NMR Biomed 1992; 5:193–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Barker PB, Soher BJ, Blackband SJ, Chatham JC, Mathews VP, Ryan RN: Quantitation of proton NMR spectra of the human brain using tissue water as an internal concentration reference. NMR Biomed 1993; 6:89–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Barker P, Breiter S, Soher B, Chatham J, Forder J, Samphilipo M, Magee C, Anderson J: Quantitative proton spectroscopy of canine brain: in vivo and in vitro correlations. Magn Reson Med 1994; 32:157–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Frahm J, Bruhn H, Gyngell ML, Merboldt KD, Hanicke W, Sauter R: Localized high-resolution proton NMR spectroscopy using stimulated echoes: initial applications to human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med 1989; 9:79–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Narayana PA, Fotedar LK, Jackson EF, Bohaw ID, Butler IJ, Wolinsky JS: Regional in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of brain. J Magn Reson 1989; 83:44–52Google Scholar

53. Michaelis T, Merboldt KD, Bruhn H, Hanicke W, Frahm J: Absolute concentrations of metabolites in the adult human brain in vivo: quantification of localized proton MR spectra. Radiology 1993; 187:219–227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Kreis R, Ernst T, Ross B: Absolute quantitation of water and metabolites in the human brain, II: metabolite concentrations. J Magn Reson series B 1993; 102:9–19Crossref, Google Scholar

55. Manji HK, Bebchuk JM, Moore GJ, Glitz D, Hasanat KA, Chen G: Modulation of CNS signal transduction pathways and gene expression by mood-stabilizing agents: therapeutic implications. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 2):27–39Google Scholar

56. Moore GJ, Bebchuk JM, Faulk MW, Parrish JK, Strahl-Bevacqua J, Hasanat K, Manji HK: Right frontal lobe choline is decreased with lithium administration in manic depressive illness. Abstracts of the Society for Neuroscience 1998; 24(2):1847Google Scholar

57. Agam G, Shapiro J, Levine J, Stier S, Shields C, Bersudsky Y, Belmaker RH: Short-term lithium treatment does not reduce human CSF inositol levels. Lithium 1993; 4:267–269Google Scholar

58. Molchan SE, Atack JR, Sunderland T: Decreased CSF inositol monophosphatase activity after lithium treatment. Psychiatry Res 1994; 53:103–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Silverstone PH, Hanstock CC, Fabian J, Staab R, Allen PS: Chronic lithium does not alter human myo-inositol or phosphomonoester concentrations as measured by 1H and 31P MRS. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:235–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Dunner DL, Bunney WE Jr: Lithium response in unipolar versus bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1972; 129:44–47Link, Google Scholar

61. Baron M, Gershon ES, Rudy V, Jonas WZ, Buchsbaum M: Lithium carbonate response in depression: prediction by unipolar/bipolar illness, average-evoked response, catechol-O-methyl transferase, and family history. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:1107–1111Google Scholar

62. Mendels J: Lithium in the treatment of depressive states, in Lithium Research and Therapy. Edited by Johnson FN. New York, NY, Academic Press, 1975, pp 43–62Google Scholar

63. Noyes R Jr, Dempsey GM, Blum A, Cavanaugh GL: Lithium treatment of depression. Compr Psychiatry 1974; 15:187–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Zornberg GL, Pope HG Jr: Treatment of depression in bipolar disorder: new directions for research. J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 13:397–408Google Scholar

65. Keck PE, McElroy SL: Outcome in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16(suppl 1):15S–23SGoogle Scholar

66. Altshuler LL, Post RM, Leverich GS, Mikalauskas K, Rosoff A, Ackerman L: Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1130–1138Google Scholar

67. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Maintenance medical treatment, in Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990, pp 665–724Google Scholar

68. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Cowdry RW: Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:179–184Link, Google Scholar

69. Wehr TA, Goodwin FK: Can antidepressants cause mania and worsen the course of affective illness? Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1403–1411Google Scholar

70. Benjamin J, Agam G, Levine J, Bersudsky Y, Kofman O, Belmaker RH: Inositol treatment in psychiatry. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:167–175Medline, Google Scholar

71. Levine J, Barak Y, Gonzalves M, Szor H, Elizur A, Kofman O, Belmaker RH: Double-blind, controlled trial of inositol treatment of depression. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:792–794Link, Google Scholar