Somatoform Disorders: Time for a New Approach in DSM-V

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: DSM-III introduced somatoform disorders as a speculative diagnostic category for somatic symptoms “not explained by a general medical condition.” Although retained and enlarged in DSM-IV, somatoform disorders have been the subject of continuing criticism by both professionals and patients. The extended period of preparation for DSM-V offers an important opportunity to reconsider the category of somatoform disorders. METHOD: Exploration of the diverse aims of a diagnostic classification indicates that the authors must not only address the conceptual and practical problems associated with this category but also reconcile it with the parallel medical descriptive classification of functional symptoms and syndromes. RESULTS: The existing somatoform disorders categories require modification. The authors favor the radical option of the abolition of the categories. Diagnoses currently within somatoform disorders could be redistributed into other groupings, and the disorders currently defined solely by somatic symptoms could be placed on axis III as “functional somatic symptoms and syndromes.” Greater use could be made of “psychological factors affecting medical condition” on axis I. The authors suggest supplementing the diagnosis of functional somatic symptoms with a multiaxial formulation. CONCLUSIONS: The authors promote a classification of somatic symptoms in DSM-V that is compatible with that used in general medicine and offers new opportunities both for research into the etiology and treatment of symptoms and for the greater integration of psychiatry into general medical practice.

DSM-III introduced the somatoform disorders as a speculative diagnostic category. It remained in the successive versions of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV. Although it has succeeded in focusing attention onto previously neglected patients with somatic symptoms that are unexplained by a general medical condition, we argue that it has failed in its declared purposes of aiding understanding, guiding research, and providing a useful basis for treating these patients (1). Since the planning process for DSM-V will allow a prolonged period for discussion and research (2), there is now an important opportunity to reconsider the somatoform disorder category. We propose a radical option: the abolition of the somatoform disorders as a category and the use of axis III to code somatic symptoms. Although this proposal is undoubtedly controversial, we hope that our arguments will both stimulate a more radical debate about how somatic symptoms are classified in DSM and inform the wider discussion about the general principles of the psychiatric diagnostic classification.

The Clinical Problem

Our starting point is the clinical problem (3). It is important to note that this is not just the small number of patients who come to psychiatrists with somatic complaints but the much larger number who are seen by all types of doctors with somatic symptoms that are not well explained by general medical conditions. Such symptoms account for a quarter to a half of presentations in both primary and secondary care (4). Although frequently minor or transient, these symptoms are often associated with a degree of distress and disability sufficient for them to be legitimately regarded as illnesses (5). Despite the size and importance of this problem, medicine—especially Western medicine—has found these conditions difficult to name, conceptualize, and classify (6). The names proposed have been bewildering in their variety and include somatization, somatoform disorders, medically unexplained symptoms, and functional symptoms. Conceptually, these illnesses lie in an ambiguous area of medical thinking somewhere between medicine and psychiatry (6). Their classification reflects this confusion: in psychiatry, they are classified as somatoform disorders (DSM-IV) and in medicine as functional somatic syndromes (5).

Current Psychiatric Terminology and Classification

The abolition of neurosis in DSM-III and its replacement by multiple new diagnoses led to acerbic debate (7). In this context, somatic syndromes that were neither explained by a general medical condition nor clearly associated with depressive or anxiety diagnoses were combined to create a new category of somatoform disorders. Central to the category of somatoform disorders was the newly proposed diagnosis of somatization disorder (8). Also included was a disparate group with other diagnoses, united only by their presentation with somatic symptoms. These diagnoses were conversion disorder, hypochondriasis, and psychogenic pain disorder. In addition, there was a residual category of atypical somatoform disorder.

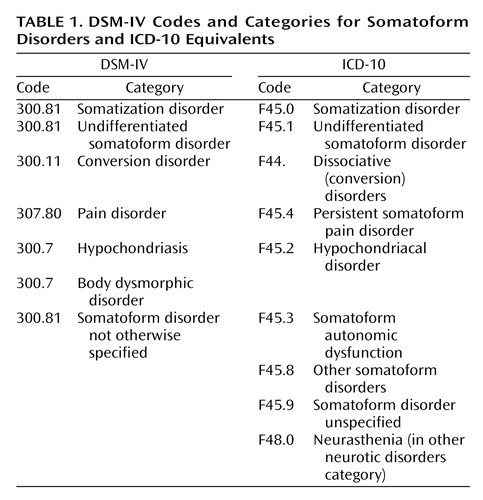

In the subsequent revisions of DSM-III as DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, minor changes to the definitions of these disorders were made. There was also one major change—the introduction of undifferentiated somatoform disorder. The addition of this new diagnosis was necessary to provide a home for the large number of patients who, although clearly ill, did not fall within the existing somatoform categories. As a result, the category of somatoform disorders changed between DSM-III and DSM-IV from being a small grouping of relatively uncommon conditions to a general category covering a wide range of illnesses. The somatoform disorders currently listed in DSM-IV are shown in Table 1. ICD-10 was developed in parallel with DSM-IV and also includes a similar, but not identical, category of somatoform disorders embedded within the broader “neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders” category (Table 1).

This review can be seen as part of a wider debate about the principles of psychiatric taxonomy that should be adopted for DSM-V. The issues under discussion include the relative merits of categorical versus dimensional approaches and the value of descriptive versus etiological classifications, the importance of utility as well as validity and reliability, the thresholds chosen for caseness, and the role of the social impairment criteria in defining caseness (9, 10). While mindful of this wider debate, this article will focus on issues specific to somatoform disorders.

The Purposes of Diagnosis

We first need to consider the main purpose of psychiatric diagnosis. In theory, this is to provide names for and categories of illnesses to aid communication, provide prognostic information, and guide treatment and research (11). In practice, however, diagnostic classifications have other functions that vary according to the user:

| • | Psychiatrists and other “mental” health specialists, especially those working in general medical settings, are often called upon to diagnose and treat patients with more severe and persistent somatic symptoms. They need diagnoses that perform the functions mentioned that also justify these conditions as appropriate for psychiatric attention. | ||||

| • | Patients are not the passive recipients of diagnoses; they also have expectations of a diagnostic label. It must be acceptable to them, appropriately represent their experience of suffering, imply a plausible explanation of what is wrong with them, and preferably lead to effective treatment. Diagnoses also have important implications for their social responsibilities and help them determine their expectations of health care and disability payments. | ||||

| • | Primary care practitioners see and manage the large majority of these patients (4). Although their primary task is to identify the symptoms that indicate serious and life-threatening medical conditions, they also have to describe and manage patients whose somatic symptoms are not associated with pathology. They need a simple and usable classification for this purpose. | ||||

| • | Employers, lawyers, insurers, those responsible for health benefits, and health planners all need a workable language and diagnostic system for all medical presentations associated with disability, health, and social costs, including those symptomatic presentations. | ||||

Shortcomings of Somatoform Disorders as Diagnoses

Although it is unrealistic to expect a diagnostic classification to meet all the demands that may be placed on it, many clinicians believe that the current terminology and classification system performs poorly in respect to almost all of the functions of diagnosis just listed.

Shortcomings of the Somatoform Category

1. The terminology is unacceptable to patients

With increasing transparency in health care, the acceptability of diagnostic terms to patients is important. Although proposed as an atheoretical term, “somatoform” is commonly seen as related to the older term “somatization” (12). This implies that the symptoms are a “mental disorder” in somatic form and may be regarded by patients as conveying doubt about the reality and genuineness of their suffering (13).

2. The category is inherently dualistic

The idea that somatic symptoms can be divided into those that reflect disease and those that are psychogenic is theoretically questionable (6). Indeed, the view that symptoms can be “explained” solely by a disease is a debatable one that is not entirely in accordance with empirical data (14). In practice, most physicians adopt a broad perspective when assessing a patient’s symptoms (15).

3. Somatoform disorders do not form a coherent category

The only common feature of somatoform disorders is that they show somatic symptoms without an associated general medical condition. Beyond that, they lack coherence (9). The overlap with the many other psychiatric disorders that are also defined in part by somatic symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, is also a potential cause of misdiagnosis.

4. Somatoform disorders are incompatible with other cultures

Somatoform disorder diagnoses do not translate well into cultures that have a less dualistic view of mind and body (for example, the current Chinese classification is based on DSM but specifically excludes the somatoform disorder category [16]). Exporting a dualistic diagnosis of somatoform disorder to these cultures at the same time that Western medicine is trying to escape it would seem to be counterproductive.

5. There is ambiguity in the stated exclusion criteria

The diagnosis of somatoform disorder requires the exclusion of general medical conditions. However, there is lack of clarity about which medical diagnoses should be regarded as exclusionary: for example, do medical “functional syndromes,” such as irritable bowel syndrome, count as exclusions? One consequence of this lack of clarity is that patients may be classified as having both an axis III disorder (for example, irritable bowel syndrome) and an axis I somatoform disorder (such as undifferentiated somatoform disorder or pain disorder) for the very same somatic symptoms. This seems to be ridiculous.

6. The subcategories are unreliable

Many of the subcategories of somatoform disorders have failed to achieve established standards of reliability (17).

7. Somatoform disorders lack clearly defined thresholds

The lack of any clearly defined threshold for what merits a somatoform disorder diagnosis has led both to disagreement about the scope of this category and also to its gradual enlargement (18). It is probably for this reason that most major epidemiological surveys of psychiatric disorders have excluded somatoform disorders.

8. Somatoform disorders cause confusion in disputes over medical-legal and insurance entitlements

Somatoform disorder diagnoses have proved problematic in relation to medical-legal and social security entitlements. On one hand, they can provide spurious diagnostic validation for simple symptom complaints, and on the other, they can undermine the reality of somatic symptoms as “merely psychiatric.” They thereby provide considerable scope for generating irresolvable differences of opinion.

In summary, the existing category of somatoform disorders may be regarded to have failed.

Shortcomings of the Specific Somatoform Subcategories

Somatization disorder is arguably the archetypical diagnosis of the somatoform disorder category. Its introduction was influenced by the then-recent work of the St. Louis group (8). Arguably, it has subsequently received attention out of proportion to its prevalence relative to that of the other somatoform disorders. Furthermore, doubts have been expressed about both its clinical value and conceptual basis (19). First, patients with somatization disorder have prominent psychological as well as somatic symptoms so that the syndrome is hardly an exemplar of a predominately somatic condition (20). Second, it has a substantial overlap with personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder (21). Third, although the requirements for diagnosis are unusual in that they rely on a lifetime history of symptoms, there is evidence that patients’ recall of past symptoms is variable and that the diagnosis has low stability in longitudinal surveys (22). Fourth, it is based merely on counting the number of “unexplained” somatic symptoms and so lacks even face validity as a psychiatric disorder. The number of somatic symptoms a person reports is continuously distributed in the general population, and the diagnosis merely represents an extreme of severity on what appears to be a continuum of distress (23). Finally, the diagnosis of somatization disorder offers the practitioner little specific guidance about treatment beyond clinical management aimed at minimizing health care use and iatrogenic illness (24).

In response to the observation that many patients with chronic multiple symptoms do not meet the DSM-IV criteria for somatization disorder, attempts have been made to reduce the number of symptoms required for a diagnosis (25, 26). Although these proposals have the advantage of acknowledging that the number of somatic symptoms forms a continuum, they retain the limitations of a diagnosis based almost exclusively on simply counting somatic symptoms.

Hypochondriasis as a diagnostic category remains controversial. Although there is good evidence of the cooccurrence of the triad of disease conviction, associated distress, and medical help-seeking, these symptoms are arguably better conceived of as a form of anxiety that happens to focus on health matters and is closely related to other forms of anxiety disorder (27, 28).

Conversion disorder has long been a problem for diagnostic classification. DSM-III placed it with other diagnoses in the somatoform section because of the shared characteristic of somatic symptoms that are not intentionally produced (7). The DSM-IV workgroup recognized a close relationship with dissociative disorders but confirmed the DSM-III classification (29). We propose that this discussion should be revisited.

Body dysmorphic disorder remains uncomfortably placed in the somatoform disorder category. There have been persuasive arguments that it should be rehoused; in particular, the suggestions that it might be better grouped with obsessive-compulsive disorder (30) could be usefully revisited.

Undifferentiated somatoform disorder was placed alongside somatoform disorder not otherwise specified (the successor to atypical somatoform disorder) in DSM-III-R as a poorly defined catchall for the patients who did not fit into the original specific DSM-III categories (31). However, it soon became clear that these were not merely small residual diagnoses but rather the most widely applicable categories. Even though this diagnosis is not widely used in clinical practice, its existence represents the need to have a diagnosis for a very large group of patients not easily classified elsewhere.

Pain disorder has undergone significant revision between DSM-III and DSM-IV. However, as noted by the Working Group for DSM-IV, there remain problems both in its definition and in establishing it as a separate disorder (32).

In summary, many of the diagnostic subcategories currently housed within the somatoform disorders either lack validity as separate conditions or could be better housed elsewhere.

The Somatoform Classification and the Evidence

We need to consider the compatibility of DSM-IV somatoform disorder with existing evidence.

Are Somatoform Disorders Consistent With Evidence About Epidemiology?

Studies of primary care patients (22, 31, 33–35) have repeatedly found that the core DSM- or ICD-defined somatoform syndromes (such as somatization disorder or hypochondriasis) are relatively rare, whereas the more vaguely defined but often clinically important diagnoses are common. This finding makes the existing classification of limited value. Measures of disease impact (such as disability or comorbid psychiatric disorder) are consistent with the apparently well-defined somatoform disorders being better regarded as the extreme on a continuum of illness (23). Population-based research also provides only limited support for the particular syndromal patterns of symptoms described by the somatoform categories (36). Cross-sectional studies report that all types of somatic symptoms (whether explained or unexplained by identifiable disease) are associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression (31, 35, 37). Furthermore, longitudinal studies have found that the type of symptoms patients report frequently varies over time (33). All of these findings raise doubts about both the validity and utility of existing somatoform disorder diagnoses.

Are Somatoform Disorders Consistent With Evidence About Etiology?

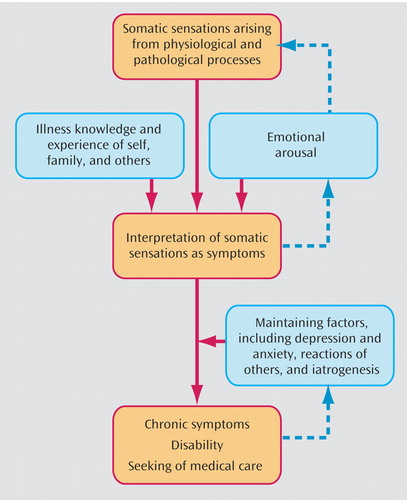

The somatoform criteria and their accompanying text are based largely on the etiological concept of “somatization,” a hypothetical process whereby mental illness manifests as somatic symptoms. Modern evidence suggests that this conceptualization is simplistic; it favors instead a multifactorial etiology with interacting psychological, social, and biological factors (38) (Figure 1). It is especially important to note that there is increasing evidence that biological factors are relevant (6). Other factors that influence symptoms include their modulation by depression and anxiety (39); processes of perception and symptoms interpretation (40); the reactions of other people (family, friends, acquaintances) (41); and iatrogenic processes, as well as the influence of the insurance, compensation, and disability systems (42).

Is the Existing Somatoform Diagnostic Classification Workable in Clinical Practice?

We have found the existing somatoform disorder category problematic in practice. The first problem is diagnostic confusion resulting from the overlap of somatoform disorders with the classification used by practitioners of internal medicine. The latter defines “functional syndromes” descriptively, according to either the patient’s major symptom (for example, dizziness, tension headache) or the bodily system that these symptoms appear to be associated with (for example, noncardiac chest pain, irritable bowel syndrome) and provides an alternative diagnosis to somatoform disorder for the same patients (5). The second problem is whether somatoform disorder can be diagnosed in patients who also have a general medical diagnosis. For example, atypical noncardiac chest pains are common and often distressing in those who have suffered myocardial infarction or undergone cardiac surgery. Should they also be given a diagnosis of somatoform disorder? The third problem relates to the conventional restriction of the diagnosis “psychological factor affecting medical condition” to patients who also have a general medical diagnosis. If a patient is distressed about somatic symptoms, should the diagnosis be somatoform disorder or psychological factor affecting a medical condition and should that depend on whether the symptoms are considered to be general medical or psychiatric in nature? In our view, the question of whether a condition is regarded as medical or as psychiatric is not an indication of etiology but simply a pragmatic statement about which medical specialty is the best place to manage it, in the same way that some conditions may be considered medical and others surgical. With these criteria, somatoform disorders may be considered to be as much general medical as psychiatric conditions.

Approaches to Change

How might we improve the current somatoform disorder classification? As a first step, we examine the features of the existing medical and psychiatric diagnostic systems that have proved to be useful and that might be incorporated into a new approach.

What Can We Learn From the Nonpsychiatric Medical Approach?

Because most patients with somatic symptoms unexplained by general medical conditions are seen by nonpsychiatric medical practitioners, we might usefully consider how these doctors currently classify them. The “nonpsychiatric” terminology and classification as functional syndromes have advantages. In particular, simple symptom descriptors, often qualified with the term “functional,” have the advantage of being atheoretical. The term “functional,” although sometimes used as a code for “psychological,” originally meant a disturbance of function as opposed to structure (43). In this sense, it is usefully nondualistic and is compatible with recent research findings that indicate altered physiological function in many of these conditions (6). It is also acceptable to patients (13). Similarly, specific functional syndrome labels, such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia, also have face validity and appear to be largely acceptable to patients. Although there is evidence for overlap (or comorbidity) among these specific functional syndromes (5), current treatment approaches generally target specific symptom clusters (such as those of irritable bowel syndrome), and simple symptoms descriptors, perhaps qualified with by the term “functional” to indicate the absence of pathologically defined disease, could usefully therefore be retained in a new classification.

What Can We Learn From the Existing Psychiatric Approach?

While we have highlighted the shortcomings of the current DSM classification in describing somatic symptoms, DSM-IV does have useful properties that could be further exploited. It has highlighted that groups of illnesses of somatic symptoms are unexplained by general medical conditions and has offered a system for classifying them. It has transcended the bodily-system-based approach of defining functional syndromes that has been shown to be of limited validity (5). Furthermore, the multiaxial nature of the system helpfully allows the separate coding of medical and psychiatric diagnoses and provides more useful information about patients than a single diagnosis.

What Should Be the Properties of the New Classification System?

We propose that any new system of classification should

| • | Be consistent with the general classification principles of DSM-V | ||||

| • | Relate effectively to the functional disorder classification used by physicians | ||||

| • | Be acceptable to patients | ||||

| • | Be etiologically neutral | ||||

| • | Be helpful in planning treatment | ||||

| • | Be equally applicable to patients with general medical conditions | ||||

| • | Provide an effective basis for further research | ||||

A Proposal for DSM-V

A conservative option would be a simple revision of the categories and definitions of somatoform disorder, accompanied by a rewriting of the accompanying text to take account of the issues outlined. This approach would, however, be similar to that taken by the DSM-IV workgroups and could consequently be expected to lead to similar difficulties. A more radical option not open to the revisers of DSM-IV would be the abolition of the category of somatoform disorders altogether, with reassignment of the specific somatoform diagnoses to other parts of the classification. We favor the second option. Our specific proposals are to

1. Abolish the somatoform disorder category.

The somatoform disorder term, concept, and category have failed psychiatrists, nonpsychiatric physicians, and patients. There seems to be little reason to retain them.

2. Adopt a new term for somatic symptoms and syndromes.

An alternative term to “somatoform” is needed to describe symptoms, especially those that are not closely related to a general medical condition. These could just be called “somatic symptoms” with an associated disease diagnosis specified when appropriate (e.g., “pain” and “pain associated with lung cancer”). If a general adjective is required to emphasize the lack of association with a general medical condition, we suggest “functional” in its original use as a strong candidate.

3. Redistribute disorders currently listed under somatoform disorders in other parts of the classification.

This task has several aspects. First, several disorders currently housed in somatoform disorders can simply be moved to other axis I (psychiatric disorders) or axis II (personality disorder) categories. Second, it could be clarified that the axis III (general medical conditions) label is to be used for all those somatic symptoms most commonly managed by general medical doctors, regardless of whether the patient has a disease diagnosis. Third, axis IV may be used to describe unhelpful interactions with medical services, as well as access to them. Specific proposals for each axis are as follows:

Axis I

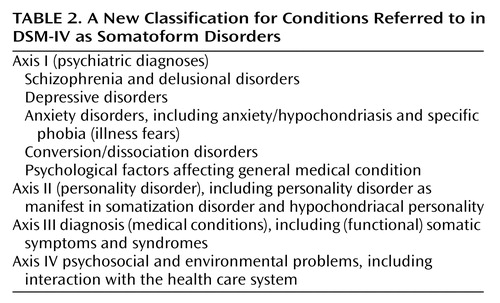

The axis I classification needs modification so that the specific diagnoses currently within somatoform disorders are either redistributed elsewhere or reformulated. The suggested revision, renaming, and redistribution of the existing somatoform categories are described here and shown in Table 2. We also argue that more use could also be made of the category “psychological factors affecting medical condition” that appears in DSM-IV only as part of the chapter titled “other conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention.” This could be an axis I accompaniment to any axis III diagnosis.

| • | Somatic symptoms associated with depression are classified with depression and those with anxiety with anxiety (with an additional specification “with prominent somatic symptoms” to reflect the patient’s preoccupation with—or concern about—somatic symptoms, such as fatigue, pain, or physical malaise). | ||||

| • | Hypochondriasis should be renamed as health anxiety disorder and placed within the anxiety disorders. Although it overlaps with other forms of anxiety, the focus on disease or medical diagnosis is clinically important and influences presentation and treatment (44). “Illness fear” probably fits best within phobias (45). | ||||

| • | Body dysmorphic disorder has never sat comfortably in the somatoform disorders category and should be moved elsewhere, possibly together with obsessive-compulsive disorder (30). | ||||

| • | The classification of dissociative and conversion symptoms requires review. One option would be to place them together as a separate subgroup defined by criteria similar to those in current use (29). | ||||

| • | The most difficult problem is the classification of the continuum of conditions defined merely by a number of somatic symptoms; this ranges from somatization disorder to undifferentiated somatoform disorder. We suggest that these symptoms are classified on axis III as “somatic symptoms” or as “functional somatic symptoms.” Associated psychiatric diagnoses could be coded on axis I with other factors justifying psychiatric intervention as “psychological factors affecting a medical condition.” Hence, the approach would be the same for a patient with irritable bowel syndrome as for a patient with illness worry after coronary artery surgery. It remains possible that it will eventually be possible to propose convincing additional psychiatric diagnoses defined by abnormalities in psychological or behavioral processes to replace this category, but this requires further research. | ||||

Axis II

| • | Patients with personality disorders as well as somatic symptoms will have their disorder coded on axis II as before. | ||||

| • | Somatization disorder may be better regarded as a combination of personality disorder (axis II) with affective or anxiety disorder (axis I) (46). | ||||

Axis III

| • | Somatic symptoms and syndromes and pain disorder could be classified on axis III. This should be seen as no more than as a clarification of the existing DSM-IV principle: “Axis III is for reporting current general medical conditions that are potentially relevant to the understanding or management of an individual’s mental disorder.” These conditions are classified outside the “Mental Disorders” chapter of ICD-9-CM (and outside chapter V of ICD-10). | ||||

| • | There would be advantages in establishing mild, moderate, and severe levels of somatic symptoms with current DSM-IV severity criteria with a threshold set so as to be of clinical significance. Somatic symptoms are defined in DSM-IV as “causes of clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” | ||||

Axis IV

Axis IV currently allows a listing of psychosocial and environmental problems. It could be usefully extended to include unhelpful interactions with the medical care system, such as frequent attendance (47).

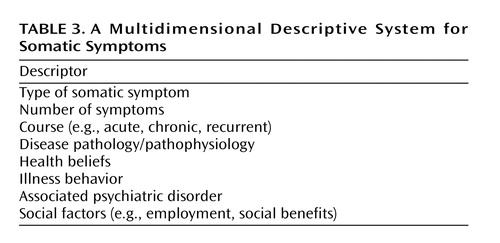

4. Elaborate on diagnoses with an additional multidimensional description.

We also argue that the new diagnostic classification would benefit from a supplementary description of individual patients in terms of descriptive dimensions as well as a diagnosis (38). An additional multidimensional classification would be consistent with our current etiological understanding. This would be valuable for more clearly defining patients to be included in research and for targeting treatment interventions at specific etiological factors. It might be reproduced as an annex to DSM-V. There are already analogies in the DSM-IV sections on pain and sleep in reference to other, more detailed classifications. A suggested scheme is shown in Table 3. This multifactorial approach could profitably be further developed and publicized not only within psychiatry but also within medicine as a whole.

Implications of the Proposals

It can be expected that the DSM-V manual will, like its predecessors, become a standard text. It will therefore have an important role in improving the general understanding of those conditions currently classified as somatoform disorders. We anticipate that if our suggestions are incorporated into DSM-V, they will have many positive implications for practice, research, and the wider understanding of these conditions. Although it would be unrealistic to expect that our proposed revisions will entirely eliminate unhelpful dualist thinking, we believe that they represent a useful step in that direction. We acknowledge that further debate and evaluation are required to adequately evaluate these proposals and to compare them with the alternative of a more limited revision of the current categories.

Clinical Implications

The main implication of our proposals is the acceptance of etiological neutrality about those somatic symptoms that are not clearly associated with a general medical condition. We propose a pragmatic classification that is explicitly based on the branch of medicine most concerned with the management of the condition rather than on presumed etiology; this has the consequence of emphasizing that some patients require attention from both general medicine and psychiatry. We anticipate that this would help integrate psychiatry with other medical specialties. It also offers a terminology and context that are more likely to be acceptable to patients and therefore more effective in engaging them in treatment. We already have treatments for functional somatic symptoms (48, 49), but we need better and less overtly “psychiatric” ways of explaining and implementing them.

Research Implications

The approach we have outlined is consistent with the evidence base and also indicates directions for further study. This research should ultimately lead to a more empirically based nosology with clearer implications for treatment. It should also clarify the etiological processes, including neurobiological, perceptual, cognitive, and behavioral factors, that underpin all symptoms. Epidemiological research could start with further analysis of existing data, for example, an examination of natural clustering and stability of syndromes over time. Finally, the supplementary multidimensional description will allow a more precise study of etiological factors and their evaluation in homogeneous groups of patients.

Wider Implications

Improved collaboration by those involved in the creation of psychiatric classifications with their nonpsychiatric counterparts will have wider benefits in encouraging a more integrated perspective on symptoms. This nonspecialty-based approach has been called symptoms research (50). Ultimately, we anticipate a merging of the classifications used by general medical and psychiatric physicians. This, in turn, will enhance the role of psychiatry in general medical care to the benefit of patients.

|

|

|

Received Nov. 22, 2003; revisions received May 31, 2004, and July 12, 2004; accepted Aug. 11, 2004. From the School of Molecular and Clinical Medicine, University of Edinburgh; the Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital, Oxford University, Oxford, U.K.; the Department of Psychiatry, Division of Social and Transcultural Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal; the Centre for Health Studies, Group Health Cooperative, Seattle; and Regenstrief Institute for Health Care, Indianapolis. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Sharpe, Kennedy Tower, Royal Edinburgh Hospital, Edinburgh EH10 5HF, U.K.; [email protected] (e-mail). Dr. Kirmayer was supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Figure 1. A Potential Etiological Model for Functional Somatic Symptomsa

aReprinted from figure 3.3 (p. 59) in chapter 3, “Treatment of Functional Somatic Symptoms,” by Richard Mayou et al., edited by Richard Mayou et al., 1995, by permission of Oxford University Press.

1. Wise TN, Birket-Smith M: The somatoform disorders for DSM-V: the need for changes in process and content. Psychosomatics 2002; 43:437–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA: A Research Agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2002Google Scholar

3. Sharpe M: Medically unexplained symptoms and syndromes. Clin Med 2002; 2:501–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kroenke K: Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2003; 12:34–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M: Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet 1999; 354:936–939Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Sharpe M, Carson AJ: “Unexplained” somatic symptoms, functional syndromes, and somatization: do we need a paradigm shift? Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:926–930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hyler SE, Spitzer RL: Hysteria split asunder. Am J Psychiatry 1978; 135:1500–1504Link, Google Scholar

8. Goodwin DW, Guze SB: Psychiatric Diagnosis. New York, Oxford University Press, 1974Google Scholar

9. Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA: Advancing DSM: Dilemmas in Psychiatric Diagnosis. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2003Google Scholar

10. First MB, Pincus HA, Levine JB, Williams JBW, Ustun B, Peele R: Clinical utility as a criterion for revising psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:946–954Link, Google Scholar

11. Kendell RE: The Role of Diagnosis in Psychiatry. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Scientific, 1975Google Scholar

12. Lipowski ZJ: Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1358–1368Link, Google Scholar

13. Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, Carson A, Lewis S, MacKenzie L, Warlow C, Sharpe M: What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? the “number needed to offend.” BMJ 2002; 325:1449–1450Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, Liu H, Browner WS, Whooley MA: Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA 2003; 290:215–221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ogden J: What do symptoms mean? BMJ 2003; 327:409–410Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Lee S: A Chinese perspective of somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res 1997; 43:115–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Simon GE, Gureje O: Stability of somatization disorder and somatization symptoms among primary care patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:90–95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Widiger TA, Clark LA: Towards DSM-V and the classification of psychopathology. Psychol Bull 2000; 126:946–963Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bass CM, Murphy MR: Somatization disorder: critique of the concept and suggestions for further research, in Somatization: Physical Symptoms and Psychological Illness. Edited by Bass CM, Cawley RH. Oxford, U.K., Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1990, pp 301–332Google Scholar

20. Wetzel RD, Guze SB, Cloninger CR, Martin RL: Briquet’s syndrome (hysteria) is both a somatoform and a “psychoform” illness: a Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory study. Psychosom Med 1994; 56:564–569Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Rost KM, Atkins RM, Brown FW, Smith GR: The comorbidity of DSM-III-R personality disorders in somatization disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003; 14:322–326Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Simon GE, Gureje O: Stability of somatization disorder and somatization symptoms among primary care patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:90–95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, Russo J, Lipscomb P, Bush T: Somatization: a spectrum of severity. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:34–40Link, Google Scholar

24. Smith GR, Monson RA, Ray DC: Psychiatric consultation in somatization disorder—a randomized controlled study. N Engl J Med 1986; 314:1407–1413Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Escobar JI, Rubio Stipec M, Canino G, Karno M: Somatic symptom index (SSI): a new and abridged somatization construct: prevalence and epidemiological correlates in two large community samples. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:140–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, deGruy FV, Hahn SR, Linzer M, Williams JB, Brody D, Davies M: Multisomatoform disorder: an alternative to undifferentiated somatoform disorder for the somatizing patient in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:352–358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL: Hypochondriasis: an evaluation of the DSM-III criteria in medical outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 43:493–500Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Salkovskis PM, Warwick HM: Morbid preoccupations, health anxiety and reassurance: a cognitive-behavioural approach to hypochondriasis. Behav Res Ther 1986; 24:597–602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Martin RL: Diagnostic issues for conversion disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:771–773Abstract, Google Scholar

30. Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr: Body dysmorphic disorder: an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder, a form of affective spectrum disorder, or both? J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56(suppl 4):41–51Google Scholar

31. Kirmayer L, Robbins JM: Three forms of somatization in primary care: prevalence co-occurrence and sociodemographic characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:647–655Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Sullivan MD: DSM-IV pain disorder: a case against the diagnosis. Int Rev Psychiatry 2000; 12:91–98Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Gureje O, Simon GE: The natural history of somatization in primary care. Psychol Med 1999; 29:669–676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Gureje O, Simon GE, Ustun TB, Goldberg DP: Somatization in cross-cultural perspective: a World Health Organization study in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:989–995Link, Google Scholar

35. Simon G, Gater R, Kisely S, Piccinelli M: Somatic symptoms of distress: an international primary care study. Psychosom Med 1996; 58:481–488Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Liu G, Clark MR, Eaton WW: Structural factor analyses for medically unexplained somatic symptoms of somatization disorder in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Psychol Med 1997; 27:617–626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Linzer M, Hahn SR, deGruy FV III, Brody D: Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med 1994; 3:774–779Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Mayou R, Bass C, Sharpe M: Overview of epidemiology classification and aetiology, in Treatment of Functional Somatic Symptoms. Edited by Mayou R, Bass C, Sharpe M. London, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp 42–65Google Scholar

39. Brenner B: Depressed affect as a cause of associated somatic problems. Psychol Med 1979; 9:737–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Pennebaker JW, Skelton JA: Selective monitoring of physical sensations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1981; 41:213–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Craig TK, Drake H, Mills K, Boardman AP: The South London Somatisation Study, II: influence of stressful life events, and secondary gain. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:248–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Nygren A: Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1179–1186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Trimble MR: Functional diseases. BMJ 1982; 285:1768–1770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Gureje O, Ustun TB, Simon GE: The syndrome of hypochondriasis: a cross-national study in primary care. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1001–1010Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Noyes R Jr, Hartz AJ, Doebbeling CC, Malis RW, Happel RL, Werner LA, Yagla SJ: Illness fears in the general population. Psychosom Med 2003; 62:318–325Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Bass C, Murphy M: Somatoform and personality disorders: syndromal comorbidity and overlapping developmental pathways. J Psychosom Res 1995; 39:403–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Bass C, Hyde G, Bond A, Sharpe M: A survey of frequent attenders at a gastroenterology clinic. J Psychosom Res 2001; 50:107–109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Kroenke K, Swindle R: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization and symptom syndromes: a critical review of controlled clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom 2000; 69:205–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, Tomkins G, Balden E, Kroenke K: Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract 1999; 48:980–990Medline, Google Scholar

50. Kroenke K, Harris L: Symptoms research: a fertile field. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:801–802Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar