Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Comorbid With Major Depression: Factors Mediating the Association With Suicidal Behavior

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to determine if patients with a history of major depressive episode and comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have a higher risk for suicide attempt and differ in other measures of suicidal behavior, compared to patients with major depressive episode but no PTSD. In addition, to explore how PTSD comorbidity might increase risk for suicidal behavior in major depressive episode, the authors investigated the relationship between PTSD, cluster B personality disorder, childhood sexual or physical abuse, and aggression/impulsivity. METHOD: The subjects were 230 patients with a lifetime history of major depressive episode; 59 also had lifetime comorbid PTSD. The demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects with and without PTSD were compared. Multivariate analysis was used to examine the relationship between suicidal behavior and lifetime history of PTSD, with adjustment for clinical factors known to be associated with suicidal behavior. RESULTS: Patients with a lifetime history of PTSD were significantly more likely to have made a suicide attempt. The groups did not differ with respect to suicidal ideation or intent, number of attempts made, or maximum lethality of attempts. The PTSD group had higher objective depression, impulsivity, and hostility scores; had a higher rate of comorbid cluster B personality disorder; and were more likely to report a childhood history of abuse. However, cluster B personality disorder was the only independent variable related to lifetime suicide attempts in a multiple regression model. CONCLUSIONS: PTSD is frequently comorbid with major depressive episode, and their co-occurrence enhances the risk for suicidal behavior. A higher rate of comorbid cluster B personality disorder appears to be a salient factor contributing to greater risk for suicidal acts in patients with a history of major depressive episode who also have PTSD, compared to those with major depressive episode alone.

In the United States, the annual prevalence of major depressive episode is about 17% (1), and 1.3% of adults ages 18–54 years experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during the course of a year (2). Between 14% and 25% of individuals exposed to catastrophic trauma develop PTSD (3–5), and as many as one-half of them have at least one additional axis I diagnosis. In 26%, the additional diagnosis is major depressive episode (6). Indeed, within 8 months of a traumatic event, 23% of exposed adults develop major depressive episode, with or without PTSD, often within days of the event (7).

Preexisting major depression increases susceptibility to the effects of traumatic events as well as ordinary stressful life events (8). At the same time, PTSD increases the risk for the first onset of major depression (9, 10). Thus, these two disorders are common and often comorbid, and the presence of one diagnosis compounds risk for the development of the other.

Both PTSD and major depressive episode are associated with risk for suicidal behavior. Lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in major depressive episode is approximately 16% (11). In a community survey, patients with PTSD were 14.9 times more likely to attempt suicide than subjects without PTSD (12). Although suicide rates are higher in Vietnam-era veterans than in the general population, studies of these veterans have yielded conflicting results regarding the degree of the difference in risk for suicide attempts and the extent of suicidal ideation in trauma victims. Some suggest that the risk of suicidal behavior in veterans with PTSD, while greater than that of nonveterans, has been overestimated (13). However, others find that specific symptoms within PTSD, such as guilt or anxiety, not the presence of PTSD in general, are responsible for higher suicide risk (14, 15)

Some (16–18) but not all (19) studies of suicidal ideation and behavior in subjects with comorbid PTSD and major depressive episode found that PTSD and major depressive episode interact to increase the level of suicidal ideation and behavior, compared with that in subjects with PTSD or major depressive episode alone. However, the relationship between major depressive episode, PTSD, and suicidal behavior is likely to be influenced by other factors. For example, child abuse increases the risk for PTSD, major depression, and suicidal behavior. About one-third of those who have been abused or neglected during childhood develop PTSD (20), and a history of childhood abuse more than doubles the odds of developing major depressive episode (21). Early childhood trauma, including abuse, has also been associated with self-destructive and suicidal behavior later in life (22, 23).

Both suicidal behavior and a childhood history of abuse and trauma are also associated with borderline personality disorder (24, 25), and some researchers have conceptualized borderline personality disorder as a form of chronic PTSD (26). In addition, borderline personality disorder is often comorbid with major depression (27). Thus, the influence of PTSD on suicidal ideation and behavior requires attention to a constellation of risk factors, including major depressive episode, personality disorder, and childhood history of abuse, as well as concomitant traits such as impulsivity and aggression that are often part of the clinical picture in cluster B personality disorders and are associated with suicidal acts.

We recently reported that patients presenting for treatment of major depression who had PTSD were more likely to have exhibited suicidal behavior and that the effect of PTSD was independent of the presence of cluster B personality disorders, childhood history of abuse, and aggressive behavior (17). We sought to replicate these findings, and in this study we examine the relationship between suicidal behavior and PTSD, while taking into account known risk factors for suicidal behavior, including cluster B personality disorders, childhood sexual or physical abuse, and history of aggression/impulsivity. We report the findings from this larger, mostly independent group of adults with a history of a major depressive episode. We hypothesize that in patients with a history of major depressive episode, those with PTSD will be more likely to attempt suicide and will differ from those without PTSD in other measures of suicidal behavior.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from inpatient units in New York (New York State Psychiatric Institute and Payne Whitney Clinic) and in Pittsburgh (Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic and St. Francis Hospital) and in both cities by advertisement. About one-half of the subjects were inpatients at the time of assessment (N=108 [49%]). Subjects (N=230) with current or past major depressive episode were entered into the study after giving written informed consent. Thirty-one subjects with a lifetime history of major depressive episode in this group were included in the study group described in our previous report (total N=156) (17), of whom six had a history of lifetime PTSD.

Assessment

Subjects were assessed for the presence of lifetime and current DSM-IV psychiatric disorder with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (28). Patients were assessed for severity of depressive symptoms by a research clinician using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (29) and by means of patients’ self-report with the Beck Depression Inventory (30). Suicide attempts were defined as self-inflicted injury with intent to end one’s life. Lifetime history of suicidal behavior was gathered by using the Columbia University Suicide History form (31). The degree of medical injury from suicide attempts was measured with the Lethality Rating Scale (32). Suicidal intent and ideation were measured with the Suicide Intent Scale (32) and the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (33), respectively. Hopelessness was assessed with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (34). Lifetime aggression was measured by using the Brown-Goodwin aggression history scale (35), hostility with the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (36), and impulsivity with the Barratt impulsivity scale (37). Axis II disorders were diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (38). Subjects were assessed for a history of physical and sexual abuse during childhood by using a series of screening questions in the demographic questionnaire.

Diagnostic Procedure

All interviewers were master’s- or doctoral-level clinicians or psychiatric nurses who received extensive training in the administration of semistructured interviews. Best-estimate diagnoses were made by consensus on the basis of all available data sources at diagnostic consensus conferences attended by research clinical staff, including psychiatrists. Within- and cross-site reliability for the SCID and SCID-II, suicide history, and the Brown-Goodwin aggression history scale were high (intraclass correlation=0.82–0.98, kappa=0.86–0.95).

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and associations between variables were examined. Demographic and clinical variables were compared in subjects with and without a lifetime history of PTSD by using Student’s t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Because not all subjects were experiencing a major depressive episode at the time of assessment, state-dependent clinical variables were compared by analysis of variance, with adjustment for Hamilton depression scale scores. We compared the age at onset of PTSD and the age at first suicide attempt of all suicide attempters with a history of PTSD. Then, a stepwise backward logistic regression was constructed with lifetime suicide attempter status as the dependent variable and lifetime PTSD, childhood history of abuse, cluster B personality disorder, impulsivity score, and aggression score as the independent variables.

Results

Subjects’ Demographic Characteristics

Fifty-nine subjects (25%) had a lifetime history of PTSD. Subjects with lifetime PTSD and subjects without PTSD did not differ significantly in age or income. Compared to subjects without PTSD, subjects with lifetime PTSD were significantly more likely to be female, nonwhite, and unmarried and to have fewer years of education (Table 1).

Severity of Acute Psychopathology

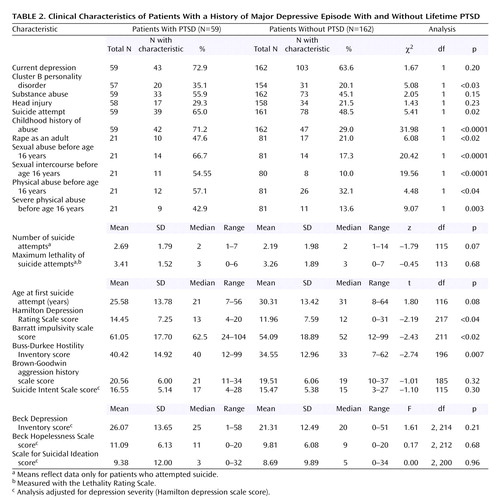

The group with lifetime PTSD had significantly higher objective depression ratings (Hamilton depression scale), compared to the group with no history of PTSD (Table 2). There were no significant differences between the groups in the level of subjective depression (Beck Depression Inventory) or hopelessness (Beck Hopelessness Scale) or in presence of a current depressive episode (Table 2).

Comorbid Conditions and Character Traits

Subjects with lifetime PTSD had significantly higher rates of comorbid cluster B personality disorders, but not of substance abuse or head injury (Table 2). Higher impulsivity (Barratt impulsivity scale) and hostility scores (Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory), but not higher lifetime aggression scores (Brown-Goodwin aggression history scale), were found in the group with lifetime PTSD.

Suicidal Behavior

Patients with lifetime PTSD were significantly more likely to have made a suicide attempt. However, contrary to our hypothesis, the groups did not differ in suicidal ideation, after adjustment for depression severity, or suicidal intent at the time of the most lethal attempt. Among subjects with a history of suicide attempt, there was no difference between the lifetime PTSD group and the group without PTSD in the number of attempts made or the maximum level of lethality of the suicide attempts. The first suicide attempt occurred at an earlier age for attempters with PTSD than for attempters with no PTSD, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

Trauma History

A significantly greater number of subjects with lifetime PTSD than of those without PTSD reported a childhood history of abuse. Lifetime PTSD subjects were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse (including intercourse) before age 16 years, physical abuse before age 16 years, severe physical abuse before age 16 years, and rape as an adult (Table 2).

Age at Onset of PTSD

For subjects with comorbid PTSD, the mean age at PTSD onset was 19.2 years (SD=14.2). Subjects with PTSD who attempted suicide (N=33) were a mean of 26 years old (SD=14) at the time of first attempt. For the most part, PTSD preceded the first suicide attempt (in 24 subjects [72%]), and the age at onset of PTSD and at first suicide attempt showed a positive correlation (Pearson’s r=0.52, N=33, p<0.002).

Multivariate Analysis

In a stepwise backward logistic regression with lifetime suicide attempter status as the dependent variable and lifetime PTSD, childhood history of abuse, cluster B personality disorder, impulsivity, and aggression as the independent variables, only cluster B personality disorder was significantly associated with suicide attempt (odds ratio=8.23, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.41–19.84, χ2=22.06, df=1, p<0.0001). The association between suicide attempt and a history of childhood abuse approached statistical significance (χ2=2.91, df=1, p=0.09) (Table 3).

In multivariate analyses, subjects with major depressive episode and cluster B personality disorder (N=29) were more likely to be suicide attempters than those with major depressive episode and lifetime PTSD (N=39) (p<0.01). However, these two groups did not differ in suicidal ideation. This finding held true when we examined the data for suicide attempters only (N=24 and N=20, respectively), and the number, lethality, and suicidal intent of attempts were similar in the two groups.

Discussion

PTSD, Major Depressive Episode, and Suicidal Behavior

We (17) and others (16) have reported that when PTSD is comorbid with major depressive episode, it is associated with higher rates of suicidal acts. In this larger group of subjects with major depressive episode, those with a lifetime history of PTSD were also significantly more likely to be suicide attempters. As in our previous study, we detected no differences in the suicidal behavior exhibited by suicide attempters—regardless of whether they had a lifetime history of PTSD—in terms of suicidal intent, number of previous attempts, age at first suicide attempt, and lethality of previous attempts.

Our previous study reported that acutely depressed subjects who currently also had PTSD had more suicidal ideation than subjects with no history of PTSD. However, no difference in suicidal ideation was seen in depressed individuals with a lifetime history of PTSD, compared to those with no PTSD ever. The present study examined subjects with a lifetime history of PTSD and major depressive episode and likewise detected no difference in suicidal ideation between those with a lifetime history of PTSD and those without PTSD. Perhaps suicidal ideation is heightened only while depressed patients are experiencing PTSD, and ideation lessens once PTSD remits. Marshall et al. (18) reported that, in subjects with symptoms of PTSD, for each additional symptom that was present, suicidal ideation was likely to occur in a larger proportion of the study group, even when the analysis controlled for the presence of major depression. However, not all studies agree. For example, Shalev et al. (19) found no difference in suicidal ideation in patients with PTSD and major depressive episode, compared to those with major depressive episode only, although the subjects were recruited from emergency services after experiencing trauma and possibly represented more acutely ill individuals. Whether suicidal ideation increases with PTSD over and above the risk conferred by depression requires further study.

Consistent with the lack of difference in suicidal ideation in the two groups, there were no significant differences between lifetime PTSD subjects and subjects with no PTSD in levels of subjective depression or hopelessness. Both groups had a similar proportion of subjects with a current depressive episode; however, PTSD subjects showed significantly higher objective depression ratings, compared to subjects with no history of PTSD. Although Golier et al. (39) suggested that comorbidity with PTSD does not result in increased severity of depressive episode, but instead is associated with more pronounced variability in mood, Shalev et al. (19) noted about twice the severity of depressive symptoms in subjects with PTSD and major depressive episode, compared to those with major depressive episode alone. Moreover, Freeman et al. (16) reported more depressive symptoms in those with PTSD and suicidal behavior, although comorbidity with depression was not established in that study. PTSD and major depressive episode share a number of symptoms, including sleep disturbance, poor concentration, guilt, restricted affect, and suicidal ideation, all of which, with the exception of restricted affect, are measured by the Hamilton depression scale. We did not measure severity of PTSD symptoms and thus cannot assess the relationship between severity of PTSD and objective severity of depression. However, given that some subjects with a lifetime history of PTSD (N=59) still had ongoing symptoms of PTSD (N=37 [62%]), it is not surprising that a history of these two disorders leads to higher ratings of depression on the Hamilton depression scale.

PTSD, Aggression, Hostility, and Impulsivity

Aggression, hostility, and impulsivity have been associated with elevated risk for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder (40), major depression (41), and PTSD (16, 42–44). In the current study group, measures of lifetime aggression were not higher in lifetime PTSD subjects, suggesting that major depressive episode and PTSD do not have an additive effect on aggression. It is noteworthy that the levels of impulsivity and hostility were higher in the group with lifetime PTSD, while the level of aggression was not. We (17) and others (7) have suggested that females may be more vulnerable to PTSD than males. Most studies of the relationship between PTSD and aggression have been conducted in predominantly male cohorts of veterans (16, 43, 44). Perhaps in this mostly female group of depressed subjects with lifetime PTSD, the presence of higher levels of impulsivity and hostility is related to the high co-occurrence of cluster B personality disorder and a childhood history of abuse. The absence of an effect on aggression may be related to the low numbers of male subjects in the study group, as only three of the 59 subjects with lifetime PTSD and major depression were male.

Trauma History, PTSD, and Cluster B Personality Disorders

A history of childhood sexual or physical abuse is associated with suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder patients (45) and in the offspring of depressed parents (46) and with high rates of self-destructive behaviors in adults with a history of sexual abuse (47). Thus, abuse during childhood may create a later predisposition to self-mutilation and suicidal behavior (45, 47). Childhood sexual and/or physical abuse has also been thought to have long-term sequelae in terms of other psychological as well as biological effects (see reference 48 for a review). For example, some (49) have characterized borderline personality disorder as a chronic form of PTSD stemming from early childhood abuse. Others suggest significant, but not complete, overlap of these two disorders and report that more than one-half (55%) of borderline personality disorder patients carry a diagnosis of PTSD (50). In the current group of patients with a lifetime history of major depressive episode, 35% of the patients with lifetime PTSD had comorbid cluster B personality disorder, compared to 20% of the patients with no PTSD. The contribution of childhood trauma to the development of PTSD and cluster B personality disorder and to their frequent co-occurrence is as yet unclear. Zlotnick et al. (51) found that women with PTSD, both with and without comorbid borderline personality disorder, had higher levels of childhood trauma than women with borderline personality disorder only, suggesting that childhood trauma is more closely associated with the development of PTSD than with the development of borderline personality disorder. This interpretation is supported by another report in which childhood trauma emerged as a risk factor for PTSD, independent of the type of comorbid personality disorder (39). In this cohort, we found that in addition to having greater comorbidity with cluster B personality disorder, patients with comorbid PTSD were also significantly more likely to report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.

Cluster B personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder, are a risk factor for suicidal behavior in depressed patients (45, 52, 53), even when the patients do not meet the full criteria for a cluster B personality disorder (54). Moreover, borderline personality disorder has been reported to have an additive effect with respect to suicidal behavior when it is comorbid with PTSD. In a nondepressed group of subjects, Zlotnick et al. (51) found that patients with borderline personality disorder or with comorbid borderline personality disorder and PTSD scored higher on measures of suicide proneness than those with PTSD only. Perhaps childhood abuse increases the liability for PTSD in the face of later traumatic events, but it is comorbidity with borderline personality disorder that elevates the risk for suicidal behavior in those with PTSD.

In contrast with our previous report, the results of the current multivariate analysis, in which cluster B personality disorder is a significant contributor to suicide attempt status, support a role for cluster B personality disorder, but not PTSD directly, in higher risk for suicidal behavior. The findings from this study suggest that the increased liability for suicidal behavior that comorbid PTSD confers is mediated by the frequency of cluster B personality disorder comorbidity. In support of this notion, Heffernan and Cloitre (55) found that women with a history of childhood abuse who had both PTSD and borderline personality disorder were more likely to engage in suicidal behavior than those with PTSD alone. Our study design did not permit tracking of the patterns and timing of onset of comorbid disorders and major depressive episode; however, it did show that, generally, the onset of PTSD antedated the first suicide attempt and that both occurred later than the reported childhood abuse. One possible explanation for our findings is that although trauma in childhood increases vulnerability to both PTSD and cluster B personality disorder, it is this latter condition that elevates the risk for suicidal behavior, possibly mediated through other associated disturbances in cluster B personality disorder that are not directly linked to childhood trauma. To dissect this relationship, prospective studies that attend to the sequence of onset of the disorders are required.

Conclusions

PTSD is frequently comorbid with major depressive disorder, and when the two disorders co-occur, the risk for suicidal behavior is enhanced. The relationship between PTSD and suicidal behavior appears to be mediated by the presence of cluster B personality disorder, with both PTSD and cluster B personality disorder arising as a result of earlier traumatic experiences. The assessment and treatment of comorbid conditions such as PTSD and cluster B personality disorder in the context of major depressive disorder are likely to contribute to the reduction of suicide risk in this vulnerable population.

|

|

|

Received Feb. 4, 2004; revision received April 26, 2004; accepted May 25, 2004. From New York State Psychiatric Institute; and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Oquendo, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 42, New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported by NIMH grants MH-56612, MH-56390, MH-55123, and MH-62185.The authors thank Dr. Dianne Currier for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Breslau N: The epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: what is the extent of the problem? J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 17):16–22Google Scholar

4. Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Gleser GC, Leonard AC, Korol M, Winget C: Buffalo Creek survivors in the second decade: stability of stress symptoms. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1990; 60:43–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kramer TL, Lindy JD, Green BL, Grace MC, Leonard AC: The comorbidity of post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidality in Vietnam veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1994; 24:58–67Medline, Google Scholar

6. Maes M, Mylle J, Delmeire L, Altamura C: Psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity following accidental man-made traumatic events: incidence and risk factors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 250:156–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM: Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA 1999; 282:755–762Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Vance KL, Kao TC, Baum A: Peritraumatic dissociation following motor vehicle accidents: relationship to prior trauma and prior major depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:267–272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L: Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:81–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women: phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depression, and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:374–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Chen YW, Dilsaver SC: Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:896–899Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Davidson JR, Hughes D, Blazer DG, George LK: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991; 21:713–721Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pollock DA, Rhodes P, Boyle CA, Decoufle P, McGee DL: Estimating the number of suicides among Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:772–776Link, Google Scholar

14. Hyer L, McCranie EW, Woods MG, Boudewyns PA: Suicidal behavior among chronic Vietnam theatre veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychol 1990; 46:713–721Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hendin H, Haas AP: Suicide and guilt as manifestations of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:586–591Link, Google Scholar

16. Freeman TW, Roca V, Moore WM: A comparison of chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients with and without a history of suicide attempt. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:460–463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Oquendo MA, Friend JM, Halberstam B, Brodsky BS, Burke AK, Grunebaum MF, Malone KM, Mann JJ: Association of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression with greater risk for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:580–582Link, Google Scholar

18. Marshall RD, Olfson M, Hellman F, Blanco C, Guardino M, Struening EL: Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1467–1473Link, Google Scholar

19. Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:630–637Link, Google Scholar

20. Widom CS: Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1223–1229Abstract, Google Scholar

21. MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, Duku EK, Walsh CA, Wong MY-Y, Beardslee WR: Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1878–1883Link, Google Scholar

22. van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL: Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1665–1671Link, Google Scholar

23. Linehan MM: Suicidal people: one population or two? Ann NY Acad Sci 1986; 487:16–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM: Childhood abuse as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord 2002; 16:201–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Mehlum L, Friis S, Vaglum P, Karterud S: The longitudinal pattern of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:124–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Gunderson JG, Sabo AN: The phenomenological and conceptual interface between borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:19–27Link, Google Scholar

27. Skodol AE, Stout RL, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Dyck IR, Oldham JM: Co-occurrence of mood and personality disorders: a report from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS). Depress Anxiety 1999; 10:175–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

29. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571{checked}Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ: Risk factors for suicidal behavior: the utility and limitations of research instruments, in Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Edited by First MB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, pp 103–131Google Scholar

32. Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M: Classification of suicidal behaviors, I: quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:285–287Link, Google Scholar

33. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42:861–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF: Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979; 1:131–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Buss AH, Durkee A: An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Psychol 1957; 21:343–349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Barratt ES: Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychol Rep 1965; 16:547–554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Benjamin L: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), Version 2.0. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

39. Golier JA, Yehuda R, Bierer LM, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Schmeidler J, Silverman JM, Siever LJ: The relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:2018–2024Link, Google Scholar

40. Soloff PH, Lis JA, Kelly T, Cornelius J, Ulrich R: Risk factors for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1316–1323Link, Google Scholar

41. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:181–189Abstract, Google Scholar

42. Kotler M, Iancu I, Efroni R, Amir M: Anger, impulsivity, social support, and suicide risk in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189:162–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Begic D, Jokic-Begic N: Aggressive behavior in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med 2001; 166:671–676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. McFall M, Fontana A, Raskind M, Rosenheck R: Analysis of violent behavior in Vietnam combat veteran psychiatric inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:501–517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Brodsky BS, Mann JJ: Risk factors for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J Calif Alliance Ment Ill 1997; 8:27–28Google Scholar

46. Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, Zelazny J, Brodsky B, Bridge J, Ellis S, Salazar JO, Mann JJ: Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: risk for suicidal behavior in offspring of mood-disordered suicide attempters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:801–807Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Boudewyn AC, Liem JH: Childhood sexual abuse as a precursor to depression and self-destructive behavior in adulthood. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:445–459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Heim C, Nemeroff CB: The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:1023–1039Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Herman JL, van der Kolk BA: Traumatic antecedents of borderline personality disorder, in Psychological Trauma. Edited by van der Kolk BA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987, pp 111–126Google Scholar

50. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V: Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1733–1739Link, Google Scholar

51. Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Yen S, Battle CL, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG, Bender DS, Zanarini MC, Shea MT: Clinical features and impairment in women with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), BPD without PTSD, and other personality disorders with PTSD. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003; 191:706–713Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Kjellander C, Bongar B, King A: Suicidality in borderline personality disorder. Crisis 1998; 19:125–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM, Malone KM, Mann JJ: Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: a comparative study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:601–608Link, Google Scholar

54. Corbitt EM, Malone KM, Haas GL, Mann JJ: Suicidal behavior in patients with major depression and comorbid personality disorders. J Affect Disord 1996; 39:61–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Heffernan K, Cloitre M: A comparison of posttraumatic stress disorder with and without borderline personality disorder among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse: etiological and clinical characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:589–595Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar