Prospective Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Following Trauma

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to prospectively evaluate the onset, overlap, and course of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression following traumatic events. METHOD: The occurrence of PTSD and major depression and the intensity of related symptoms were assessed in 211 trauma survivors recruited from a general hospital's emergency room. Psychometrics and structured clinical interview (the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale) were administered 1 week, 1 month, and 4 months after the traumatic event. Heart rate was assessed upon arrival at the emergency room for subjects with minor physical injury. Twenty-three subjects with PTSD and 35 matched comparison subjects were followed for 1 year. RESULTS: Major depression and PTSD occurred early on after trauma; patients with these diagnoses had similar recovery rates: 63 survivors (29.9%) met criteria for PTSD at 1 month, and 37 (17.5%) had PTSD at 4 months. Forty subjects (19.0%) met criteria for major depression at 1 month, and 30 (14.2%) had major depression at 4 months. Comorbid depression occurred in 44.5% of PTSD patients at 1 month and in 43.2% at 4 months. Comorbidity was associated with greater symptom severity and lower levels of functioning. Survivors with PTSD had higher heart rate levels at the emergency room and reported more intrusive symptoms, exaggerated startle, and peritraumatic dissociation than those with major depression. Prior depression was associated with a higher prevalence of major depression and with more reported symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Major depression and PTSD are independent sequelae of traumatic events, have similar prognoses, and interact to increase distress and dysfunction. Both should be targeted by early treatment interventions and by neurobiological research.

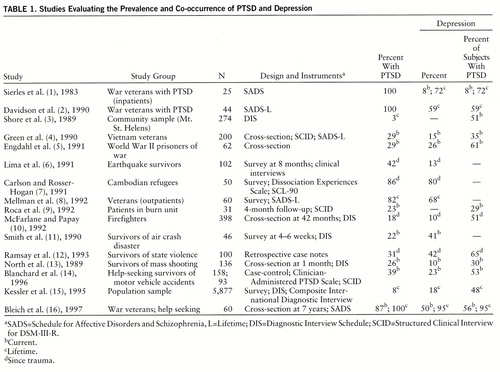

An extensive literature associates the exposure to traumatic events with the occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Major depression has also been associated with stressful life events and with PTSD (table 1) (1–16). The co-occurrence of depression and PTSD (concurrent: up to 56%; lifetime: 95% [16]) exceeds the expected effect of simple coincidence. Alternative explanations include similarity in symptoms, common causation, and sequential causation, in which depression is assumed to be secondary to prolonged PTSD. Specific attributes of traumatic events may contribute to the occurrence of either PTSD or depression.

Symptoms of depression are frequently observed among survivors but seem to be more intense in those with PTSD. For example, Holocaust survivors with PTSD report more depressive symptoms than those without PTSD (17). Vietnam veterans hospitalized for PTSD had higher Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores than veterans admitted for major depression (18). A significant correlation between the intensity of early PTSD symptoms and the occurrence of depression 19 months later has been documented in survivors of a marine disaster (19). The presence of comorbid depression seems to predict chronicity of PTSD (10, 20).

Studies evaluating the onset of PTSD and major depression following trauma arguably associate chronological order with causality. Most of these studies are retrospective and therefore rely on memory for sequence of remote events. Nevertheless, they suggest that depression is often “secondary” to PTSD. In the National Comorbidity Study, for example, 78.4% of subjects with comorbid major depression and PTSD reported that the onset of their affective disorder followed that of PTSD (15). Vietnam combat veterans similarly reported that the onset of phobias, major depression, and panic disorder followed that of PTSD (8). In a study of Israeli combat veterans, however, PTSD and depression started together in 65% of the cases, major depression preceded PTSD in 16% of the cases, and PTSD preceded major depression in 19% (16). The last study, however, addressed depression in help-seeking PTSD patients, examined 4–6 years after the war.

Psychiatric morbidity before the traumatic event seems to increase the likelihood of developing both PTSD and depression upon exposure (21, 22). However, Smith et al. (11) found that predisaster depression predicted depression but not PTSD. Prior mental disorders may interact with trauma intensity: Resnick et al. (23) found a positive association between precrime depression and PTSD in rape victims exposed to high crime stress but not in those exposed to low crime stress. Conversely, Foy et al. (24) found that family history of psychiatric disorders predicted PTSD in low combat exposure but not in high combat exposure.

The contribution of gender to development of PTSD has been evaluated by several authors (15, 20, 21). Differences in type of exposure have been found; female subjects are more frequently exposed to rape and molestation, and males are more frequently exposed to combat, accidents, and physical attacks and have a higher prevalence of exposure in general (15, 20). The likelihood of developing PTSD upon exposure, however, was found to be higher in female subjects (15, 21).

The degree of exposure during a traumatic event has been specifically associated with the occurrence of PTSD. Exposure to atrocities was a specific predictor of PTSD, but not of depression, among Vietnam veterans (25). The intensity of torture predicted PTSD in civilians exposed to state violence (12, 26). Finally, in young Cambodian refugees, stressors that followed the trauma were associated with depression, whereas trauma intensity predicted PTSD (7).

The previous studies are limited by design and method. Specifically, most are retrospective, some have evaluated acute and others chronic PTSD, many have addressed help-seeking survivors, and few have used both continuous and categorical measures. Hence, they leave the following questions unanswered (27): Are major depression and PTSD independent consequences of trauma, each having its own course and prognosis? Which symptoms are shared, and which others separate the two disorders? Is there a hierarchy, such that prolonged PTSD is the cause of subsequent major depression or otherwise “dominates”? The present study addresses these questions, using a longitudinal design, starting at the time of the traumatic event and following subjects into the stage of chronicity.

METHOD

As previously described in detail (28), patients arriving at the emergency room of a general hospital were recruited over a period of 3 years. Patients were examined by a research psychiatrist and were considered for inclusion if they were between 16 and 65 years old and had experienced an event meeting DSM-III-R criterion A for PTSD. Patients were not included if they suffered from head injury, burn injury, current or lifetime abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs (relatively rare in Israel), past or present psychosis, or life-threatening medical illness.

Subject candidates received information describing the study, were invited to participate, and gave written informed consent. They were subsequently assessed 1 week, 1 month, and 4 months after the traumatic event. A selected subgroup was assessed again 1 year after the traumatic event (see later discussion). The assessments included structured clinical interviews and self-reported and interviewer-generated psychometric material. Heart rate was recorded upon the subjects' arrival at the emergency room (see later discussion and reference 29).

Structured clinical interviews included the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (30) and the Hebrew version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (31). Both instruments had been validated and used in previous studies (28, 29, 32, 33), and both were administered by clinicians with extensive experience in diagnosis and treatment of PTSD. PTSD status was determined according to DSM-III-R criteria as measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Current and lifetime diagnoses of major depression were identified through use of the SCID.

Psychometric instruments included the Impact of Event Scale (34), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (35), Beck Depression Inventory (36), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (37), the civilian version of the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (38), and Peritraumatic Dissociation Experiences Questionnaire (39). The Impact of Event Scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Mississippi scale, Hamilton depression scale, Peritraumatic Dissociation Experiences Questionnaire, and Beck inventory have been used in previous studies and will not be described here (for details regarding the Peritraumatic Dissociation Experiences Questionnaire see references 28 and 33). An immediate response questionnaire included 14 items to assess the intensity of physical (e.g., pain), emotional (fear, anger), and negative cognitive (e.g., expecting doom) experiences during the traumatic event. Each item was rated 1 to 10 (1=none, 10=highest possible intensity), yielding response intensity scores ranging from 14 to 140. Finally, 12 professional raters, blind to the subjects' diagnostic status, listened to audiotaped scripts describing the traumatic events, as reported by each subject 1 week after the trauma (for details on script generation and recording see references 32 and 40), and rated event severity on a 1–10-point scale (1=not severe at all, 10=extreme severity). Event severity scores were averaged across the 12 raters.

Upon the subject's presentation to the emergency room, a registered nurse used a vital signs monitor to obtain heart rate. In order to avoid confounds related to physical injury, only subjects with minor injuries, who were released to their home within 12 hours of arrival at the emergency room, were included in the analyses of heart rate responses (N=84).

In order to evaluate the long-term outcome of early PTSD, subjects with PTSD at 4 months (N=37) were invited to attend an evaluation session 1 year after their traumatic events; 32 (86.5%) were located, and 23 (62.2%) were interviewed. Subjects with PTSD who were not assessed (N=9) included seven who did not wish to attend and two who were in the midst of litigation and wanted to use their follow-up visit to support their legal case. Thirty-five age- and gender-matched comparison subjects, without PTSD at 4 months, were also assessed 1 year after the trauma.

During the 1-week interview (mean=7.6 days after the trauma, SD=3.0), subjects provided a detailed description of the traumatic event and completed the Impact of Event Scale, state scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Beck inventory, Hamilton depression scale, and Peritraumatic Dissociation Experiences Questionnaire. One-month interviews (mean=32.9 days following trauma, SD=6.4) and 4-month interviews (mean=116.7 days following trauma, SD=29.4) also included the Mississippi scale and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. The Peritraumatic Dissociation Experiences Questionnaire, which evaluated reactions at the time of the trauma, was not repeated.

RESULTS

Subjects, Noncompletion, and Exclusion

Of 420 traumatized individuals whose agreement was sought in the emergency room, 270 (64.3%) initially agreed to participate in the study, and 211 of those (78.1%; 103 men and 108 women) completed all interviews. Traumatic events among those who completed all interviews included road traffic accidents (N=181, 85.8%), work and domestic accidents (N=15, 7.1%), terrorist acts (N=9, 4.3%), combat events (N=4, 1.9%), and physical assault (N=2, 0.9%). The distribution of traumatic events among subjects who completed all interviews resembles that observed among 4,514 trauma survivors seen in the emergency room over a year in that the majority of traumatic events (N=3,670, 81.3%) were road traffic accidents, followed by 748 (16.6%) work and domestic accidents and 96 (2.1%) war events and terrorist attacks.

Subjects who did and did not complete all interviews had similar age and gender distribution, had undergone similar traumatic events, and had similar response-intensity scores. The groups differed, however, in 1-week psychometric scores (F=3.20, df=4,267, p=0.03, multivariate analysis of variance [MANOVA]), with post hoc tests (Tukey's honestly significant difference for unequal sample sizes) showing lower 1-week scores on the Impact of Event Scale for subjects who did not complete all interviews than for those who did (mean=18.9, SD=12.1, versus mean=27.9, SD=8.7) (p<0.01). Thus, subjects who did not complete the interviews tended to report fewer symptoms than those who did.

Occurrence of PTSD and Comorbidity

Sixty-three subjects (29.9%) met diagnostic criteria for PTSD at 1 month, and 37 (17.5%) had PTSD at 4 months. Forty subjects (19.0%) met criteria for major depression at 1 month, and 30 (14.2%) had major depression at 4 months. Comorbidity between major depression and PTSD was present at 1 month, and its frequency remained stable across time, affecting 28 (44.4%) of 63 PTSD patients at 1 month and 16 (43.2%) of 37 PTSD patients at 4 months. PTSD and major depression also occurred in isolation; between 1 and 4 months 30 individuals met criteria for PTSD without ever meeting criteria for major depression (42.2% of all PTSD), while 17 individuals had major depression without ever having PTSD (29.3% of all major depression). Forty-one individuals met criteria for both disorders at 1–4 months.

Mobility within the diagnostic categories was very similar in that it consisted primarily of progressive recovery (the term recovery is used here in the restricted sense of not meeting full diagnostic criteria for a disorder). The recovery rate of subjects with major depression did not differ statistically from that of subjects with PTSD. By 4 months 27 (67.5%) of 40 subjects with major depression at 1 month had recovered from major depression, and 34 (54.0%) of those with PTSD at 1 month had recovered from PTSD (p=0.49, Fisher's exact probability test). Finally, 13 (9.6%) of 136 individuals without mental disorder at 1 month developed diagnosable disorders at 4 months, including PTSD (N=2, 1.5%), major depression (N=3, 2.2%), and comorbid PTSD and major depression (N=8, 5.9%).

Recovery among subjects with comorbid disorders at 1 month did not differ from that observed among subjects without comorbidity. Nineteen subjects with comorbid PTSD and major depression at 1 month (67.9% of 28) had recovered from PTSD by 4 months, compared with 20 (57.1%) of 35 without comorbid major depression (χ2=0.76, df=1, p=0.38). Similarly, 19 subjects with comorbid disorders at 1 month (67.9%) had recovered from major depression by 4 months, compared with eight (66.7%) of 12 subjects with major depression alone (χ2=0.01, df=1).

Subjects' gender did not affect the frequency of PTSD and major depression at 1 month or 4 months. The ratios of men to women were as follows: at 1 month—PTSD, 29:34, and major depression, 17:23 (maximum likelihood χ2=1.66, df=4, p=0.80); at 4 months—PTSD, 22:15, and major depression, 13:17 (maximum likelihood χ2=6.09, df=4, p=0.19).

Symptom Severity

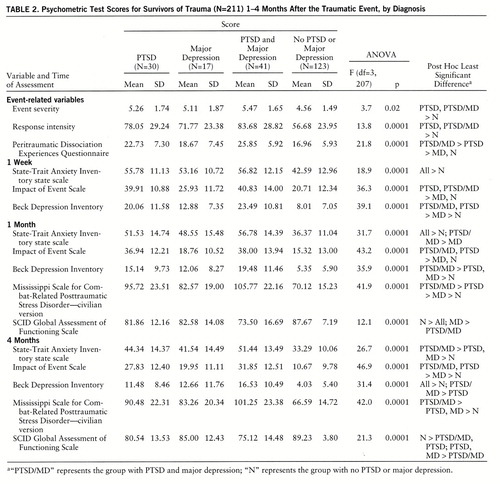

Subjects with comorbid PTSD and major depression tended to report more symptoms and were judged to have lower functioning (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale from the SCID). Table 2 provides means, analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and post hoc comparisons among four diagnostic groups: PTSD, major depression, comorbid PTSD and major depression, and those with neither PTSD nor major depression between 1 and 4 months. Given the large differences between subjects with a mental disorder and those without, MANOVAs comparing the three groups with diagnoses (PTSD, major depression, comorbid disorders) were performed on all psychometric interviews, at each stage of the study, yielding significant differences at 1 week (F=3.63, df=6,170, p<0.002), 1 month (F=3.71, df=8,168, p<0.001), and 4 months (F=1.94, df=8,168, p<0.05).

Stepwise logistic regression evaluated the relative contribution of 1-month diagnostic status to PTSD at 4 months. Having PTSD at 1 month significantly predicted PTSD at 4 months (χ2=15.53, df=1, p<0.0001); having major depression did not improve significantly that prediction (difference in χ2=1.51, df=2, p=0.22); and having comorbid PTSD and major depression added significantly to predictions made from both PTSD and major depression status (added χ2=35.95, df=3, p<0.0001).

Symptom Overlap and Specificity

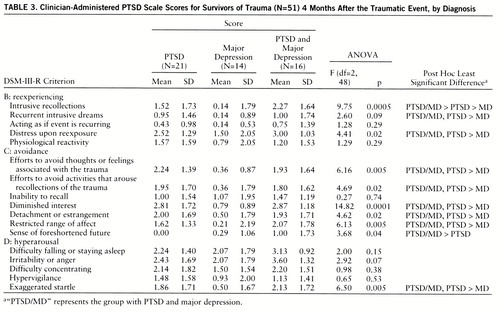

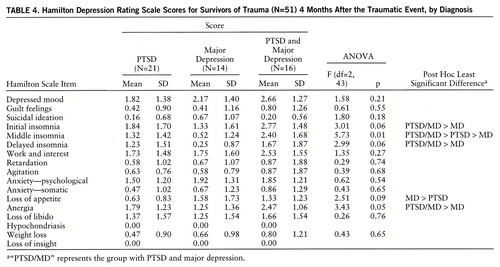

In order to compare the diagnostic groups on symptoms of PTSD and depression, 4-month Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale frequency scores and Hamilton depression scale scores are reported: symptoms at 4 months were less likely to reflect an acute response to the trauma than were those recorded at 1 month. As shown in table 3, the groups with PTSD alone and comorbid PTSD and major depression differed from the major depression group on several Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale items. MANOVA for clusters B, C, and D yielded the following: F=2.37, df=10,88, p<0.02; F=3.71, df=14,82, p<0.0001; and F=1.98, df=12,82, p<0.05, respectively. The PTSD and major depression groups differed in PTSD symptoms that are typically thought to reflect depression (i.e., diminished interest, detachment or estrangement, restricted range of affect, and sense of a foreshortened future). The groups had similar levels of hyperarousal symptoms (with the exception of exaggerated startle). As for depressive symptoms, the groups had comparable Hamilton depression scale scores (MAN~OVA F<1), although the PTSD group reported more insomnia and the major depression group reported greater loss of appetite (table 4).

Heart Rate Responses

The occurrence of posttraumatic disorders among subjects evaluated for heart rate (N=84) did not differ from that among the four diagnostic groups: At 4 months 15 subjects (17.9%) had developed PTSD, 23 (27.4%) had comorbid PTSD and major depression, four (4.7%) had major depression, and 42 (50.0%) had no disorder (total χ2=3.93, df=3, p=0.27). The mean heart rate levels at the emergency room were as follows: for patients with PTSD, mean=94.6 bpm, SD=18.1; for comorbid PTSD and major depression, mean=87.3, SD=12.4; for major depression, mean=83.5, SD=4.8; and for no disorder, mean=82.3, SD=9.9. ANOVA for heart rate was significant (F=3.83, df=3,80, p<0.02), with post hoc tests (Tukey's honestly significant difference) showing significantly higher heart rate for subjects with PTSD than for subjects with no disorder (p<0.05). This difference remained significant when event severity was controlled by means of analysis of covariance (F=2.82, df=3,77, p<0.05; post hoc [PTSD versus no disorder] p<0.04).

Effect of Prior Depression

Forty-eight individuals (22.8% of 211) had suffered from major depression before the traumatic event. Subjects with prior depression did not differ from all others in age and trauma severity but had higher Beck inventory scores at 1 week (mean=19.47, SD=11.64, versus mean=11.06, SD=9.72) (t=4.98, df=209, p<0.0001), 1 month (mean=15.42, SD=11.71, versus mean=8.36, SD=8.69) (t=4.40, df=209, p<0.0001), and 4 months (mean=12.74, SD=9.78, versus mean=6.81, SD=8.60) (t=4.02, df=209, p<0.0001) and higher Mississippi scale scores at 1 month (mean=96.52, SD=22.94, versus mean=77.42, SD=21.93) (t=4.93, df=209, p<0.0001) and 4 months (mean=91.93, SD=32.12, versus mean=73.74, SD=21.53) (t=4.95, df=209, p<0.0001).

Within 4 months of the traumatic event eight of the subjects with prior depression (16.6%) had developed major depression, 15 (31.3%) had developed comorbid depression and PTSD, and seven (14.6%) had developed PTSD. PTSD, major depression, and comorbid major depression and PTSD following trauma occurred more frequently in subjects with prior depression than in those without prior depression (for PTSD: χ2=4.13, df=1, p<0.05; for major depression: χ2=13.04, df=1, p<0.0005; for comorbid major depression and PTSD: χ2=5.02, df=1, p<0.03).

1-Year Follow-Up

The subgroup of subjects followed for 1 year (N=58; 28 men and 30 women) did not differ from those who were not followed (N=153) in type of traumatic event (road traffic accidents in 50 [86.2%] and 131 [85.6%], respectively) and in symptom intensity at 1 week, 1 month, and 4 months. MANOVAs for all psychometric interviews at each stage showed no main effect of being in the 1-year follow-up group, a consistent main effect of having PTSD at 4 months (for 1 week: F=9.14, df=5,197, p<0.0001; for 1 month: F=14.13, df=6,199, p<0.0001; for 4 months: F=35.72, df=8,195, p<0.0001), and no interaction between PTSD status at 4 months and being in the 1-year follow-up group.

Thirteen subjects who were followed for 1 year had comorbid PTSD and major depression at 4 months, and 10 had PTSD alone. Comorbidity at 1 year was very similar, with eight (61.5%) of 13 subjects having PTSD and major depression (χ2<1). Recovery from comorbid PTSD and major depression at 4 months was somewhat lower (yet statistically nonsignificant) than that from PTSD or major depression alone: 40.0% versus 54.5% for PTSD and 62.5% for major depression (χ2=2.08, df=6, p=0.36). Finally, prior depression (N=16) was associated with a greater risk of having major depression at 1 year and with higher 1-year Beck inventory and Mississippi scale scores (Beck inventory: mean=16.82, SD=14.59, versus mean=6.68, SD=9.28 [t=2.80, df=57, p<0.01]; Mississippi scale: mean=104.28, SD=30.75, versus mean=76.25, SD=25.54 [t=3.29, df=57, p<0.002]).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that extreme events can be associated with the early and simultaneous development of both PTSD and major depression or a combination thereof. The remission rates of these disorders were similar. The intensity of depressive symptoms in PTSD resembles that of major depression, yet the disorders differed in symptoms of insomnia, intrusion, and auditory startle. Individuals with comorbid PTSD and major depression reported more symptoms. Prior depression was associated with a greater risk for developing major depression and with reporting more symptoms across time.

In contrast with most previous studies (8, 15) but consistent with that of Bleich et al. (16), this study does not show a chronological development leading from PTSD to major depression. Our results support the idea (10, 20) that within PTSD depressive symptoms predict severity, but clear prediction of chronicity was not observed. Event severity and response intensity did not differentiate PTSD from major depression (as would be predicted given previous studies [7, 10, 11, 25, 26]), but this may be explained by similarity between the traumatic events (short incidents, followed by immediate rescue) in this study. Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores for subjects with mental disorders, in this study, were relatively high, yet this may be because of the early stage of the disorder and lack of chronic impairment.

Elevated heart rate levels at the emergency room were specifically associated with PTSD. These data suggest that early autonomic activation may be specifically linked with subsequent PTSD, while the mechanisms that mediate the occurrence of depression may be of a different nature.

In reading these results one should be aware of the study's limitations, which include a relatively short follow-up period, a group of survivors of single and short events, and sampling from an emergency room of a general hospital. Other traumatic circumstances, such as rape, disaster, captivity, or torture, may involve different degrees of loss, humiliation, relocation, or prolonged exposure and may result in different ratios of depression and PTSD. However, the occurrence of depression at the early stages of such short events argues that these widely acceptable predictors of sadness and helplessness are not necessary in order to trigger depressive disorders among survivors.

Indeed, the salient finding of this study is the co-occurrence of PTSD and major depression following trauma and their complex interaction. Such knowledge argues for a broader conceptualization of the response to traumatic events, going beyond the present emphasis on PTSD. Future studies should, therefore, address the occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among survivors. They should also go beyond categorical outcome measures to include continuous dimensions of the response to trauma, such as symptoms and bodily responses. Finally, early treatment interventions should target both PTSD and depression.

|

|

|

|

Received June 18, 1997; revision received Oct. 30, 1997; accepted Dec. 11, 1997. From the Center for Traumatic Stress, Department of Psychiatry, Hadassah University Hospital; and Manchester VA Research Service, Harvard Medical School, Manchester, N.H. Address reprint requests to Dr. Shalev, Department of Psychiatry, Hadassah University Hospital, P.O. Box 12000, Jerusalem, 91120, Israel; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH research grant MH-50379.

1 Sierles FS, Chen J-J, McFarland RE, Taylor MA: Posttraumatic stress disorder and concurrent psychiatric illness: a preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1177–1179Link, Google Scholar

2 Davidson JR, Kudler HS, Saunders WB, Smith RD: Symptom and comorbidity patterns in World War II and Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:162–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Shore JH, Vollmer WM, Tatum EL: Community patterns of posttraumatic stress disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:681–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Green BL, Grace MC, Lindy JD, Gleser GC, Leonard A: Risk factors for PTSD and other diagnoses in a general sample of Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:729–733Link, Google Scholar

5 Engdahl BE, Speed N, Eberly RE, Schwartz J: Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and personality profiles of American World War II prisoners of war. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:181–187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Lima BR, Pai S, Santacruz H, Lozano J: Psychiatric disorders among poor victims following a major disaster: Armero, Columbia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:420–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Carlson EB, Rosser-Hogan R: Trauma experiences, posttraumatic stress, dissociation, and depression in Cambodian refugees. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1548–1551Link, Google Scholar

8 Mellman TA, Randolph CA, Brawman-Mintzer O, Flores LP, Milanes FJ: Phenomenology and course of psychiatric disorders associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1568–1574Link, Google Scholar

9 Roca RP, Spence RJ, Munster AM: Posttraumatic adaptation and distress among adult burn survivors. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1234–1238Link, Google Scholar

10 McFarlane AC, Papay P: Multiple diagnoses in posttraumatic stress disorder in the victims of a natural disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:498–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Smith EM, North CS, McCool RE, Shea JM: Acute postdisaster psychiatric disorders: identification of persons at risk. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:202–206Link, Google Scholar

12 Ramsay R, Gorst Unsworth C, Turner S: Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of organised state violence including torture. A retrospective series. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:55–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 North CS, Smith EM, McCool RE, Shea JM: Short-term psychopathology in eyewitnesses to mass murder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:1293–1295Abstract, Google Scholar

14 Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos WR, Forneris CA, Jaccard J: Who develops PTSD from motor vehicle accidents? Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:1–10Google Scholar

15 Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Bleich A, Koslowsky M, Dolev A, Lerer B: Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:479–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Yehuda R, Kahana B, Southwick SM, Giller EL Jr: Depressive features in Holocaust survivors with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1994; 7:699–704Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Southwick SM, Yehuda R, Giller EL Jr: Characterization of depression in war-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:179–183Abstract, Google Scholar

19 Joseph S, Yule W, Williams R: The Herald of Free Enterprise disaster: the relationship of intrusion and avoidance to subsequent depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther 1994; 32:115–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Breslau N, Davis GC: Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:671–675Link, Google Scholar

22 McFarlane AC: The aetiology of post-traumatic morbidity: predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:221–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL, Kramer TL: Vulnerability-stress factors in development of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:424–430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Foy DW, Resnick HS, Sipprelle R, Carroll EM: Premilitary, military, and postmilitary factors in the development of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Therapist 1987; 10:3–9Google Scholar

25 Breslau N, Davis GC: Posttraumatic stress disorder: the etiologic specificity of wartime stressors. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:578–583Link, Google Scholar

26 Basoglu M, Paker M, Paker O, Ozmen E, Marks I, Incesu C, Sahin D, Sarimurat N: Psychological effects of torture: a comparison of tortured with nontortured political activists in Turkey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:76–81Link, Google Scholar

27 Keane TM, Wolfe J: Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder: an analysis of community and clinical studies. J Appl Soc Psychol 1990; 20:1776–1788Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T: Predicting PTSD in civilian trauma survivors: prospective evaluation of self report and clinician administered instruments. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:558–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Shalev AY, Sahar T, Freedman S, Peri T, Glick N, Brandes D, Orr SP, Pitman RK: A prospective study of heart rate responses following trauma and the subsequent development of PTSD. Arch Gen Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

30 Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM: A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behavior Therapist 1990; 13:187–188Google Scholar

31 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

32 Shalev AY, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Psychophysiologic assessment of traumatic imagery in Israeli civilian patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:620–624Link, Google Scholar

33 Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S: Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:219–225Link, Google Scholar

34 Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Speilberger CD: Manual for State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983Google Scholar

36 Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL: Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: three studies in reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:85–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Kulka RA, Hough RL: Peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress in male Vietnam theater veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:902–907Link, Google Scholar

40 Pitman RK, Orr SP, Forgue DF, Altman B, de-Jong JB, Herz LR: Psychophysiologic assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder imagery in Vietnam combat veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:970–975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar