Use of Mental Health Services by Veterans With PTSD After the Terrorist Attacks of September 11

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Community surveys have demonstrated significant psychological distress since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Since people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental illnesses are especially vulnerable to stressful events, the authors examined the use of PTSD treatment services and other mental health services at Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers in New York City and elsewhere after the attacks. METHOD: Analysis of variance was used to compare changes in average daily service use in the 6 months before and the 6 months after September 11, with changes in service use across the same months in the 2 previous years. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences from previous years in the proportion of new patients (i.e., who had not received treatment in the previous 6 months) entering treatment after September 11. RESULTS: There was no significant increase in the use of VA services for the treatment of PTSD or other mental disorders or in visits to psychiatric or nonpsychiatric clinics in New York City after September 11 and no significant change in the pattern of service use from previous years. Nor was there a significant increase in PTSD treatment in the greater New York area, Washington, D.C., or Oklahoma City or in the proportion of new patients. CONCLUSIONS: No increase was observed in the use of mental health services among VA patients with PTSD or other mental illnesses in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11.

There has been widespread concern that the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, resulted in sustained psychological distress not only among those directly affected by the loss of life and physical destruction but also among other residents of the cities that were attacked and even among Americans whose exposure was limited to televised images of death and destruction (1–3). Surveys of New York City residents conducted during the second month after the attacks found significantly elevated evidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (2, 3), with the highest rates found among residents directly affected by the tragedy who were at the World Trade Center on September 11 or who lived nearby. A national survey that focused on communities that were not directly attacked (1) found evidence of substantial symptoms of stress in 44% of adults and 35% of their children 3–5 days after September 11. The authors concluded that the events of September 11 had serious adverse effects on adults who were not directly exposed, a result that is consistent with research on responses to other traumatic events (4, 5), although a survey conducted 1 month after the tragedy failed to find higher levels of distress or evidence of PTSD outside of New York City (3). There has also been a concern that the psychological damage caused by the attacks would result in dramatic increases in the need for and use of mental health services (6).

People with preexisting PTSD or other mental illnesses were likely to be especially vulnerable to the events of September 11. A meta-analysis of 77 studies (7) concluded that a past history of psychiatric disorder is one of the most consistent predictors of vulnerability to PTSD and that past exposure to trauma, although somewhat less consistent, also significantly increases the risk. Several studies have shown that military veterans are prone to reactivation of PTSD when exposed to subsequent trauma (8–10).

To evaluate the impact of the events of September 11 on vulnerable populations, we used national administrative data from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system to compare use of both mental health and general medical services during the 6 months before and after September 11. The VA serves a large chronically mentally ill population of veterans and provides specialized services for veterans with military-related PTSD at each of its New York City facilities. Following the literature (7), we hypothesized that increased use of such services would be especially likely among veterans with war-related PTSD and also among those with serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and major affective disorder and those with substance abuse or other psychiatric disorders. Clinical experience suggests that the description in the media of immolation, body parts, and physical destruction would trigger painful memories of Southeast Asia for some Vietnam veterans, exacerbating PTSD symptoms, and stimulating additional clinical visits among patients in current treatment, as well as efforts to initiate treatment by others.

Because the VA has a national health care system with common-workload data systems in all of its medical centers, we also explored geographical variation in patterns of greater service use. We hypothesized that increases would be greatest at VA medical centers in New York City, followed by the greater New York area (Long Island, Westchester County, and northern New Jersey), Washington, D.C., other large cities in the Northeast, and Oklahoma City, because of its past experience of terrorism. Service use at VA medical centers in other U.S. metropolitan areas and in general medical clinics was examined for comparison.

Method

Sample

The sample included all patients who received services from VA medical centers located in the 40 largest U.S. cities (11) in the 180 days before and the 180 days after September 11 in 1999, 2000, and 2001.

Sources of Data

Data were obtained from national VA administrative workload databases: the Patient Treatment File, a discharge abstract documenting all episodes of inpatient care, and the outpatient care and encounter files documenting all visits to VA outpatient clinics.

Measures

To simultaneously capture changes in service use resulting from greater numbers of veterans seeking treatment and more visits per veteran, the primary dependent variables used were the total number of outpatient visits for selected diagnoses, the number of visits to selected specialty clinics, and the number of admissions to psychiatric inpatient units per working day (i.e., weekends and holidays were excluded). Eight types of services were examined in separate analyses:

| 1. | Outpatient visits with a primary or secondary diagnosis of PTSD (ICD-9 code 309.81). | ||||

| 2. | Visits with a primary or secondary diagnosis of substance abuse (ICD-9 codes 291.00–292.99, 303.00–305.99). | ||||

| 3. | Visits with a primary or secondary diagnosis of more serious mental illnesses, schizophrenia, major affective disorder, or other psychosis (ICD-9 codes 295.01–298.99). | ||||

| 4. | Visits in which any mental illness was diagnosed (including those listed) (ICD-9 codes 290.00–312.99). | ||||

| 5. | Visits to specialized outpatient PTSD clinics (clinic stop codes 519, 525, 540, 561, or 580). | ||||

| 6. | Visits to any specialty mental health clinic (clinic stop codes 500–599). | ||||

| 7. | Admissions to psychiatric inpatient units (bed section codes 70–79, 84, 89, 90–93). | ||||

| 8. | Visits to primary care or specialty medical clinics (clinic stop codes 300–399). | ||||

VA medical centers located in the 40 largest U.S. cities were classified into six geographic regions:

| 1. | New York City (Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx). | ||||

| 2. | The greater New York area (Long Island, Westchester County, northern New Jersey). | ||||

| 3. | Washington, D.C. | ||||

| 4. | Other metropolitan areas in the Northeast (New York and New England). | ||||

| 5. | Oklahoma City. | ||||

| 6. | Other U.S. metropolitan areas (i.e., the South, Midwest, and West). | ||||

Observations were further classified by dichotomous variables reflecting the year of the observations (2000 or 1999=0, 2001=1) and by their temporal relationship to September 11 (before=0, after=1).

To evaluate change in service use at different intervals after September 11, observations after that date were further classified as occurring during the first month after September 11, during the second or third month, or during the fourth through sixth months.

Veterans seeking services in the 6 months after September 11 in each year were considered new patients if they had not received medical services in the 6 months before September 11.

Analyses

We used t tests to compare the average number of outpatient visits and inpatient admissions of various kinds per working day in New York City before and after September 11, as well as in 1999 and 2000. Analysis of variance was then used to evaluate the interaction of time (6 months before or after September 11) and year (2001 versus 1999 or 2000) to determine whether the trends in 2001 were different from those in previous years.

These analyses were then repeated for each of the three post–September 11 time intervals, and a comparable set of analyses were conducted for each of the other geographic areas and for female veterans and veterans under age 40 in New York City.

Since our main analyses were based on measures of the average units of service delivered per day, it is possible that the number of veterans could have significantly increased while the number of visits per veteran decreased, or vice versa. To evaluate this possibility, we repeated our analyses of each category of service use to examine separately changes in the number of users and changes in the average number of services received per user during the 6 months before and after September 11 in comparison with previous years.

In addition, chi-square tests were used to examine differences from previous years in the proportion of new patients (i.e., who had not received treatment in the previous 6 months) entering treatment after September 11.

Because each set of analyses involved 12–16 comparisons, we used both the conventional uncorrected p<0.05 and a more conservative Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of 0.004 as the criteria of statistical significance.

Results

Service Use in New York City

At VA medical centers in New York City, there was no significant increase in the mean daily delivery of services for the treatment of PTSD or any of the other types of mental health or medical services in the 6 months after September 11, although there was an 8.8% decrease in the number of visits by patients with a diagnosis of substance abuse that was significant at p<0.05 but not at the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of p<0.004 (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the mean number of daily visits from previous years for any service (interaction of time and year).

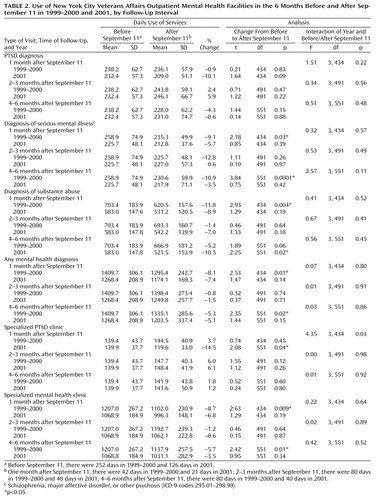

Although the 6-month period after September 11 was divided into subunits (1 month, 2–4 months, 3–6 months), again there was no significant increase in the mean number of daily visits for the treatment of PTSD in 2001 at any time interval or any significant difference in the pattern of change from previous years (Table 2). The lack of evidence of significantly more visits for the treatment of PTSD was also found in 2001 for all other types of mental health service use. However, at the conventional alpha level of p<0.05, there was a significant decrease in the number of outpatient substance abuse visits 4–6 months after September 11 and a decrease in the number of visits to specialized PTSD clinics in the first month after September 11, although these changes were not significant at the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of p<0.004. The analyses of New York City residents were repeated for the subgroups of female veterans and veterans under age 40, also with no evidence of increased service use after September 11.

Service Use in Other Metropolitan Areas

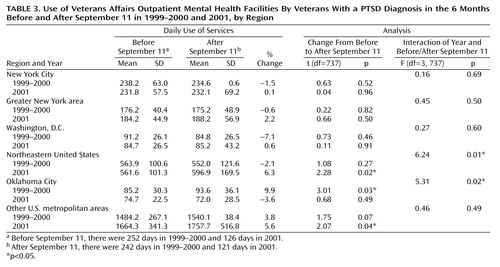

After September 11, there was no increase in the number of visits for which a diagnosis of PTSD was recorded in the greater New York area or in Washington, D.C., the areas most directly affected by the attack after New York City itself (Table 3). The visits for the treatment of PTSD in Oklahoma City, an area that may have been especially vulnerable to evocations of past terrorist attacks, actually declined after September 11 in 2001, although they had increased in 1999–2000—a significant interaction at p<0.05 although not at p<0.004. There were increases in the number of visits for the treatment of PTSD in Northeastern metropolitan areas other than New York and in other metropolitan areas across the United States (Table 3), and there was a significant interaction in the Northeast (at p<0.05 but not at p<0.004), indicating that the increase in PTSD treatment visits in fiscal year 2001 represented a departure from the pattern of service use in previous years. This finding is not consistent with the hypothesis that greater use of services would be greatest in locations that were directly affected by the events of September 11 than elsewhere.

Reanalysis of all six categories of outpatient visits for mental health services and of general medical visits with patient-level data showed no significant increase in the average number of visits per user for any of the seven categories of outpatient service use when we compared the 6 months after September 11 with the 6 months before or the changes in service use in 2001 with those of previous years (data available on request). In one of the seven categories (visits to specialized mental health clinics), there was an increase in the number of individuals who had clinical visits in the period before to the period after September 11 in 2001 (2.6%, N=290), although there had been a decline in previous years (–1.1%, N=243) (χ2=5.05, df=1, p=0.03). However, with Bonferroni correction for 14 comparisons, the required alpha level for significance would be p<0.004.

New Patients

There were no significant increases, compared to each previous year, in the proportion of new veterans (i.e., who had not received treatment in the previous 6 months) entering treatment after September 11 in any of the health service categories (data available on request).

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no evidence of significantly greater VA service use for the treatment of PTSD or other mental disorders in New York City after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, or any evidence of increased use of mental health services in comparison to previous years. These patterns were similar to those for general medical care.

Perhaps the most parsimonious interpretation is that the attacks of September 11 did not induce or exacerbate psychiatric problems enough to stimulate greater service use. Mental health service use is an imperfect proxy for psychological distress since many factors other than psychological distress affect the use of mental health services among veterans and nonveterans alike (12–14). Lack of such an increase is not evidence that there was no distress in this population. It is evidence, however, that the distress was not of the magnitude or type that leads to greater use of services or direct health care costs (although there were substantially greater security costs at VA facilities in New York after September 11, and extensive support was provided beyond the VA medical center there to agencies such as the fire and police departments and the New York City Family Assistance Centers) (personal communication, M. Losonczy, June 25, 2002).

Numbing of emotions and avoidance are important symptoms of PTSD, and it is possible that veterans were initially so overwhelmed by these reactions that they were unable to seek additional services. While such reactions may partially explain the decline in PTSD–related visits in the first month after September 11, they were not likely to have sustained their initial intensity for 6 months. For instance, a 4-month prospective study of civilian trauma victims in Israel showed substantial reduction in symptoms after the first month after the traumatic event (15), and preliminary evidence has been presented that reactions to September 11 in New York and elsewhere subsided after the first few months (16, 17).

Based on previous research (7–10), we expected the most vulnerable subgroup to be veterans with a current or past history of PTSD, the vast majority of whom served in the Vietnam conflict (18), but that other vulnerable subgroups, such as veterans with serious mental illness or substance abuse disorders, might also be affected. No evidence of increased service use was observed in any specialized PTSD or other clinics, suggesting that while veterans with PTSD and other mental disorders, like all Americans, were disturbed by the attacks of September 11, their responses to events might have been experienced as powerful and disturbing but normal. These are expectable emotional reactions rather than exacerbations of psychopathology that would require additional professional services, a distinction that has been emphasized by other researchers studying the psychological effects of terrorism (19). These findings are consistent with evidence that there was no increase in mental health services use in the general populations of New York City (17) or Washington, D.C. (20), in the immediate aftermath of September 11.

Emotional reactions to the events of September 11 may have been ameliorated by the national outpouring of support for New Yorkers, the memorial services honoring the dead, and the opportunities for volunteer activity and charitable giving. Extensive discussions of emotional reactions to the attacks in the media, at informal street memorials around New York and at ordinary social gatherings, may also have helped veterans cope.

Potential Impediments to Service Use

It is also possible that documented service use did not increase because of significant barriers. Transportation was disrupted in the aftermath of September 11, and some patients may have been afraid to venture into the city. In addition, some off-site VA counseling involving contact with individuals of unknown VA eligibility may not have been captured by the national data systems. While these impediments could have suppressed the documented delivery of services shortly after September 11, their effect would likely have diminished 4–6 months later.

Other possible explanations of these negative findings might be that 1) the VA had no capacity to accept additional patients, 2) all potential patients were already receiving optimal services and there was no need for additional services, or 3) Vietnam veterans distrust the VA as part of a government that sent them to fight an unpopular war and would not have sought help from the VA under any condition.

These explanations also seem unlikely. During the period 3–6 months after September 11, when transportation barriers would have been at their lowest, the rates of service use were actually lower than before September 11 in five of six service categories (Table 2). One would not expect to see lower rates of service use if the demand for services was stretching VA clinical capacity to its limit. In fact, VA administrators in the New York area, anticipating greater demand for mental health services, monitored service use closely and identified supplemental clinical resources but did not find occasion to deploy them (personal communication, M. Losonczy, June 25, 2002).

Second, VA administrative data (18) show that in the New York area, only 60% of the veterans receiving VA compensation for PTSD and only 8% of those in the highest priority eligibility categories for VA health care (those with service-connected disabilities and low-income veterans) used VA mental health services in 2001. Thus, there were many veterans who were specifically disabled by PTSD, as well as many others who were not using VA services.

Finally, several studies have shown that combat veterans, and Vietnam veterans with PTSD in particular, show a preference for VA over non–VA services (12, 13). The number of veterans receiving VA services for the treatment of PTSD has increased steadily in recent years (18), further demonstrating both the capacity of the VA to expand services and a willingness of the veteran population to use VA services when needed.

Geographic Patterns

An extensive literature suggests that proximity to traumatic events is among the most important risk factors for PTSD and related symptoms (1–3, 7). We did not find evidence of greater effects in New York or Washington, D.C., compared with other parts of the United States. In fact, the only areas of the country that did show increased use of PTSD services were metropolitan areas elsewhere in the Northeast (upstate New York and New England) and other parts of the country that were not directly attacked. It may be that the usual epidemiological patterns were reversed in the case of trauma related to September 11 and that stress was greater farther from the area directly affected. However, other studies of reactions to September 11 have shown the expected geographic gradient in stress responses (2, 3). The absence of expected geographic patterns, in fact, lends support to the view that the events of September 11 did not increase mental health service use among populations that previous research has suggested would be at high risk for exacerbation of PTSD or stress-related symptoms.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is that it only addressed use of formal mental health and general medical services and provided no direct information on use of emergency services or services provided at VA Readjustment Counseling Centers (i.e., “vet centers”), informal service use, perceived barriers to care, or symptoms or subjective distress. Epidemiological surveys are needed to assess the impact of the events of September 11 on the psychological health of the nation and to document unmet needs and potential barriers to service use, if they exist. This study, however, provides the first suggestion that the events of September 11, at least in the first 6 months, had little impact on the actual use of mental health services by a population with ready access and high risk.

A further limitation of this study is that the data addressed VA service users only, 95% of whom are men; among those treated for PTSD, the average age is 53 years (19). Our findings, thus, may not be generalizable to women, younger adults, and especially children, about whom there have been parental reports of significant distress after the events of September 11 (1–3). There is some evidence that older adults may be less reactive to disasters (21, 22). However, we found no difference in our findings when we repeated the analyses among female veterans and veterans less than 40 years of age.

Conclusions

This study did not find evidence of greater mental health service use after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, among veterans in New York City. While epidemiological studies are needed to more fully assess the range of psychological sequelae and perceived barriers to service use among New York veterans, these findings concerning actual service use are that veterans were able to cope with their emotional experiences successfully enough that they did not seek increased professional assistance.

|

|

|

Received Aug. 19, 2002; revision received Dec. 27, 2002; accepted Jan. 14, 2003. From the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center; the VA New England Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, West Haven, Conn.; the Evaluation Division of the National Center for PTSD, West Haven, Conn.; the Department of Psychiatry and the School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rosenheck, 182, VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1507–1512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Galea S, Ahern S, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2001; 346:982–987Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, Jordan KB, Rourke KM, Wilson D, Thalji L, Dennis JM, Fairbank JA, Kulka RA: Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the national study of Americans’ reactions to September 11, 2001. JAMA 2002; 288:581–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Dixon P, Rehling G, Shiwach R: Peripheral victims of the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. Br J Med Psychol 1993; 66:193–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pfefferbaum B, Seale TW, McDonald NB, Brandt EN Jr, Rainwater SM, Maynard BT, Meierhoefer B, Miller PD: Posttraumatic stress two years after the Oklahoma City bombing in youths geographically distant from the explosion. Psychiatry 2000; 63:358–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Susser ES, Herman DB, Aaron B: Combating the terror of terrorism. Sci Am 2002; 287: 70–77Google Scholar

7. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD: Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:748–766Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McCarroll JE, Fagan JG, Hermsen JM, Ursano RJ: Posttraumatic stress disorder in US Army Vietnam veterans who served in the Persian Gulf War. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:682–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Solomon Z, Garb R, Bleich A, Grupper D: Reactivation of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:51–55Link, Google Scholar

10. Long N, Chamberlain K, Carol V: Effect of the Gulf War on reactivation of adverse combat-related memories in Vietnam veterans. J Clin Psychol 1994; 50:138–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Statistical Abstract of the United States:1999 (119th ed). Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 1999Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck RA, Massari LA: Wartime military service and utilization of VA health care services. Mil Med 1993; 158:223–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck RA, Fontana AF: Do Vietnam era veterans who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder avoid VA mental health services? Mil Med 1997; 160:136–142Google Scholar

14. Gelberg L, Anderson RM, Leake BD: The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000; 34:1273–1302Medline, Google Scholar

15. Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:630–637Link, Google Scholar

16. Langer G: Psychological sequelae of September 11 (letter). N Engl J Med 2002; 347:443–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Galea S, Resnick H, Vlahov D: Response to G Langer; CW Hoge: Psychological sequelae of September 11 (letters). N Engl J Med 2002; 347:443–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Fontana A, Rosenheck R, Spencer H, Grey S: Long Journey Home, X: Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs: Fiscal Year 2001 Service Delivery and Performance. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2002Google Scholar

19. North CS, Pfefferbaum B: Research on the mental health effects of terrorism. JAMA 2002; 288:633–636Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hoge CW, Pavlin JA, Milliken CS: Psychological sequelae of September 11 (letter). N Engl J Med 2002; 347:443–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Thompson MP, Norris FH, Hanacek B: Age differences in the psychological consequences of Hurricane Hugo. Psychol Aging 1993; 8:606–616Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Norris FH, Phifer JF, Kaniasty K: Individual and community reactions to the Kentucky floods: findings from a longitudinal study of older adults, in Individual and Community Responses to Trauma and Disaster: The Structure of Human Chaos. Edited by Ursano RJ, McCaughey BG, Fullerton CS. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 378–400Google Scholar