Use of Mental Health Services After Hurricane Floyd in North Carolina

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to examine the impact of a natural disaster, Hurricane Floyd, on the use of mental health services in a Medicaid population in North Carolina. METHODS: Difference-in-differences techniques were used to determine month-by-month and 12-month postevent average effects of the hurricane on the use of mental health services at the county level. The exposure group was drawn from 14 severely affected counties, and the control group was drawn from 56 unaffected counties. Data were analyzed from July 1998 (14 months before the hurricane) to September 2000 (12 months after the hurricane). RESULTS: The number of per-enrollee per-month outpatient visits to psychologists or licensed clinical social workers and the number of outpatient visits to non-mental health specialists showed a statistically significant increase over the 12-month postevent period, whereas the number of inpatient admissions for behavioral health reasons decreased. Dollars spent on antianxiety medication per enrollee per month showed a statistically significant decrease. CONCLUSIONS: The aftermath of Hurricane Floyd was associated with significantly greater use of mental health services in the Medicaid community in North Carolina for a few services. However, it is unclear whether changes in utilization patterns were due to the greater demand for services or to the availability of other services that may have served as substitutes. The results of this study underscore the importance of planning for service implementation and delivery after similar events in other states.

A growing body of literature is emerging on the impact of natural and man-made disasters on the use of general medical and mental health services. Substantial evidence exists that disasters produce emotional trauma and psychological disorders (1,2,3). Research has focused both on the general population and on specific effects on defined subpopulations, such as persons with severe mental illness (4,5) and disaster survivors (6). Most of this literature is cross-sectional; only a few studies have examined reactions to disasters from a longitudinal perspective (7). Amid current community preparedness concerns, there is increased interest in how disasters affect not only mental health status but also demand for and use of mental health services.

The literature is mixed on the impact of disasters on the use of mental health services. Some evidence indicates increased service use, whereas other research suggests that service use does not change after a disaster. The premise of this article is that this inconsistency in findings may be due to variations over time in the use of mental health services after a disaster, a period during which service use is not stable—rather, it fluctuates in the days, weeks, and months after the disaster.

Thus the impetus for this study was our proposition that findings are largely dependent on the stage of the postdisaster period during which service use data are obtained. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is by definition a disorder that emerges over time, although its precise onset after a trauma is variable. Whether and when help-seeking behavior occurs for both physical and mental concerns is an area of uncertainty and is likely dependent on a myriad of personal, social, and environmental factors. Measuring help-seeking behavior and service use at a single point in time after a disaster provides an incomplete profile of how disasters affect service use. In this study, we examined mental health service use both in the predisaster period and in monthly intervals postdisaster. Our goal was to better understand the dynamic nature of service use after a disaster by using several measures of service use.

On September 16, 1999, Hurricane Floyd hit both coastal and inland areas of North Carolina. The storm was and remains the worst natural disaster in the state's history. Flooding caused massive economic upheaval in the eastern part of the state, including some inland areas that do not generally suffer the full devastating effects of hurricanes. In some parts of North Carolina, 15 to 20 inches of rain fell over a 12-hour period, with the highest winds reaching 130 miles per hour. Hurricane Floyd was directly responsible for 51 deaths, with total damage of more than $6 billion (8). The hurricane resulted in loss of homes and considerable displacement and jolted the lives of thousands of residents.

Natural and man-made disasters pose a unique and often overwhelming challenge to mental health service providers (9). The magnitude of Hurricane Floyd presented an opportunity to longitudinally examine the hurricane's effect on the use of mental health services. Through a comparison of mental health service use among all Medicaid recipients in severely affected counties as well as those that were not affected, we sought to identify variations in service use after the hurricane. A clearer understanding of service use patterns after a disaster may help clinicians and disaster planners anticipate changes in demand for services during various postdisaster periods.

Clinically, one would expect an increase in the need for services for PTSD, depression, and anxiety in the days, weeks, and months after a disaster. Families and individuals may suffer displacement from their homes and death or injury of loved ones. The suddenness of natural disasters and the inability to prepare physically and mentally may lead to the emergence of mental health problems among individuals who had not previously used mental health services.

In this study we examined service use associated with a natural disaster, but we did not assess the actual need for services. Whether increased need translates into increased service use is a separate question. Individual treatment-seeking behavior, service availability and system capacity, and financial support for services all affect the likelihood that a disaster will result in greater use of services.

Our review identified few empirical studies of the impact of natural disasters on service use. Caldera and colleagues (3) interviewed individuals who had been affected by Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua and found that every respondent met at least one criterion for a PTSD diagnosis. Although symptoms clearly increased, as did reports of help-seeking behavior, mental health service use was not addressed in this study. However, those who exhibited mental disorders before the hurricane were nearly five times as likely to seek help after the hurricane than those who did not exhibit symptoms before the hurricane. Six months after the hurricane, half of those interviewed still exhibited PTSD symptoms. Although utilization data were not provided, the results of the study suggest that a natural disaster has long-term effects on mental health and perhaps on service use.

Unlike the study by Caldera and colleagues, which focused on the general population, the study by McMurray and Steiner (4) examined the impact of the 1998 Montreal ice storm on persons with severe mental illness in an outpatient community treatment program. Comparing psychiatric hospital admission rates before and after the storm, these researchers found no impact on the likelihood of hospitalization. This finding challenges the assumption that environmental stressors necessarily lead to increased use of services among persons with severe mental illness and are somewhat at odds with the findings of Caldera and colleagues. Although differences exist in the context of the two studies—one focused on the entire population and the other on persons with severe mental illness—postdisaster service use patterns are more complex than suggested by either study alone.

Several studies found increased stress and symptoms after disasters. Abrahams and colleagues (10) found that self-medication—for example, sleeping tablets and psychotropic drugs—as well as irritability, nervous tension, and depression increased among flood victims in Australia. Similarly, Carr and colleagues (11) found that more than 21 percent of residents of Newcastle, Australia, increased their use of support services in the months after an earthquake.

Sacco and colleagues (12) examined use of mental health services in the general population of New York City after the Northeaster of 1992. They found that many individuals were initially resistant to obtaining services and did not seek them because of fear of stigma or distrust of government. However, after these individuals were provided with an explanation of the services, ten of 60 families agreed to receive some form of in-home care, including mental health services. That study addressed a chronic issue of the relationship between "need" and utilization: although individuals may have an increased need for mental health services after a catastrophic event, this increase may not result in increased service use because of other factors—in this instance, stigma and distrust.

In a 2002 comprehensive review of 20 years of research on the mental health consequences of disasters, Norris and colleagues (13) found considerable variation in the impact of disasters. Some studies showed minimal or transient stress reactions, whereas others showed highly prevalent and persistent psychopathology. Of particular relevance to the study reported here is the finding that "severe, lasting, and pervasive psychological effects" are more likely to result when at least two of the following factors are present: extreme and widespread damage to property; serious and ongoing financial problems for the community; human carelessness or, in particular, human intent as a cause of the disaster; and high prevalence of trauma in the form of injuries, threat to life, and loss of life (13). It is clear that three of these factors were present in the most severely affected counties in North Carolina, suggesting that the psychological impact was likely to be severe.

Data are limited on the impact of man-made disasters on symptoms and the use of mental health services. Contrary to expectations, Rosenheck and Fontana (14) found that veterans with preexisting PTSD were less symptomatic at admission after September 11, 2001, than those who were admitted before September 11. Examining mental health service use after September 11, these authors found no significant increase in the use of Department of Veterans Affairs services for the treatment of mental disorders (15). This study of utilization was unusual in that it reported use of services longitudinally after September 11. We used the same basic approach in the study reported here.

The preceding review of this modest body of literature clearly indicates that mental health status is affected by the destabilization and trauma resulting from catastrophic events. However, it is not clear how this increase in psychological distress translates into service use; the patterns and fluctuations of service use after disasters are not well understood. In the study reported in this article, we focused specifically on the population living in areas directly and severely affected by a disaster. This group is most likely to experience the destabilizing effect of a disaster, exhibit mental disorders, and require mental health services. The study examined the nature of fluctuations in service use after a disaster.

Methods

Data

We studied aggregate data on service use by all North Carolina Medicaid recipients in counties that were severely affected by the hurricane, using recipients in counties that were unaffected as controls. We used administrative claims data from July 1998 through September 2000; this period includes 14 months before and one year after the hurricane. We examined pre-hurricane service use to identify trends in utilization—for example, seasonal patterns—that were unrelated to the hurricane. The data were longitudinal, meaning that individual service use could be observed from the beginning to the end of the study period. These data capture all services paid for by the North Carolina Medicaid program during that period. We tracked utilization for a substantially longer period than is customary in the literature on disasters because of evidence that the use of mental health services after a disaster may remain at an increased level well beyond the event, at times up to and beyond one year (16). We do not report individual-level characteristics, because the analyses used aggregated data from all enrollees. No limitations were placed on the duration of Medicaid enrollment.

We identified behavioral health service use through diagnostic and procedure codes embedded in the data set. Although many substance abuse treatment services are not covered by North Carolina Medicaid, providers may code substance abuse diagnoses for most types of services, so we used the presence of either mental health or substance abuse diagnosis codes to identify behavioral health services. These utilization measures overcounted the number of visits that were focused only on behavioral health services or conditions but allowed us to examine visits that were at least partly for complications from or direct treatment of a behavioral heath condition, as reflected by the diagnostic and procedure codes. We examined eight indicators of utilization. For outpatient utilization, we examined the number of outpatient visits per enrollee per month to psychiatrists, psychologists, or licensed clinical social workers (not distinguishable in our data from visits to psychologists), mental health centers, non-mental health specialists for mental health or substance abuse reasons, and emergency departments.

We also examined the number of hospital admissions for which a behavioral health diagnosis was recorded, and looked separately at dollars spent on antidepressant and anxiolytics (labeled "antianxiety" in our data). Non-mental health specialists refer to all other health care providers whose specialty is not mental health and who are compensated through the Medicaid program in North Carolina. Aggregate visits by provider type were examined separately to determine whether any effects observed varied by provider. Data were aggregated to the county-month level and reflect the number of visits and cost of antidepressant and antianxiety medication used by persons in each county and month during the study period. No exclusions were made for continuous enrollment or other enrollee characteristics.

We compared these measures of utilization among Medicaid recipients in counties that were severely affected with those that were not affected by the hurricane. We used the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) designation to identify the 14 most severely affected counties (17). The 56 unaffected counties were used as the comparison group. Minimally and moderately affected counties (N=30) were excluded because our focus was on the impact in severely affected counties. The inclusion of minimally affected counties may have masked significant differences in utilization.

Statistical analysis

Difference-in-differences models were run, using ordinary least-squares regression, by including terms controlling for time invariant county characteristics through fixed effects, a linear time trend, and an interaction term between a variable indicating the severely affected counties and one indicating the period after the hurricane; this latter interaction variable is the main variable of interest, and its coefficient is the only one reported in the tables. All county-level observations are weighted by the number of Medicaid enrollees each month. We allowed for a separate linear time trend for severely affected counties throughout the study. Robust standard errors are reported.

Results

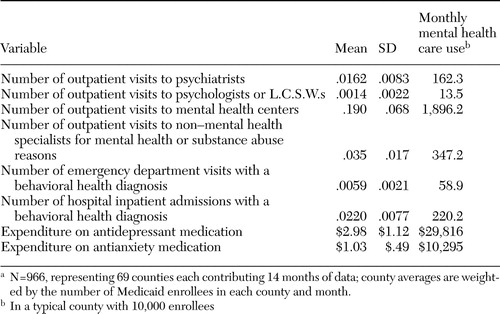

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the measures used in our sample counties, averaged across the prestorm period. Mental health centers were by far the largest source of outpatient behavioral health visits, with an average of 1,896 visits per 10,000 enrollees per month. Visits to psychiatrists and non-mental health specialists were less frequent, and visits to psychologists or L.C.S.W.s were relatively infrequent (13.5 visits per 10,000 enrollees per month). A typical county had fewer than 60 emergency department admissions for which a behavioral health diagnosis was recorded and 220 behavioral health inpatient admissions.

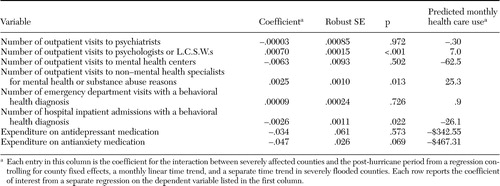

Table 2 presents regression results for mental health service use in severely affected counties compared with use in unaffected counties over the 12-month post-hurricane period. The number of visits to both psychiatrists and mental health centers declined slightly in affected counties—on the order of four visits and 751 visits per 10,000 enrollees per year, respectively—but this difference was not statistically significant. The number of visits to psychologists and L.C.S.W.s was slightly higher in affected counties after the hurricane, on the order of 84 annual visits per 10,000 enrollees. The use of generalists for mental health purposes was also slightly higher in affected counties, with a total on the order of 304 annual visits per 10,000 enrollees. We found no difference in the number of visits to emergency departments, but the number of behavioral health inpatient visits was 10 percent lower. We found no significant difference in expenditure on antidepressant medication, and a relatively small ($.05 per enrollee per month, or 4 percent) decrease in spending on antianxiety medications over the first year after the storm. In addition, we examined the aggregate number of outpatient behavioral health visits to providers of any type tied to new users of behavioral health services, defined as individuals who did not obtain any behavioral health care during the previous six months. We found an aggregate increase in the number of visits for new users in affected counties after the storm on the order of eight visits per month per 10,000 Medicaid enrollees (data not shown).

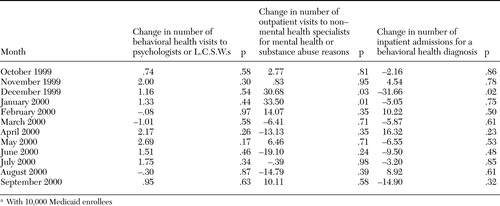

The estimates in Table 2 show the average monthly effect on mental health services use for the year after the hurricane but do not tell us when these changes occurred during the postdisaster period. Using the three variables for which there were statistically significant increases during this period, we further explored these results through similar regressions that isolated the effect of the dependent variables each month after the storm. In Table 3 we present the monthly effects for a typical county with 10,000 enrollees for the three variables with statistically significant monthly changes. In addition, the two indicators of medication use did not exhibit statistically significant differences in the regressions reported in Table 2 on changes over the full post-hurricane period but did exhibit some statistically significant changes in the monthly regressions. These results are not reported, both because of space constraints and because no observable pattern was discernable.

Differences were calculated as the average monthly difference in utilization per 10,000 enrollees between severely affected counties and nonaffected counties, controlling for pre- and post-hurricane time trends. We should note that the "estimates" were generated from data for 100 percent of the population, not a sample of the Medicaid population. Therefore, because we are not making inferences about the "entire population," statistical significance and confidence intervals do not take on the meaning they would traditionally have in a study that samples only a portion of the population. Given that there is some debate about the meaning of statistical significance in a study of an entire population—for example, a case could be made that our study represents only a "sample" of an infinite number of similar studies—we provide information on statistical significance.

Table 3 indicates very small monthly changes in the number of visits to psychologists or L.C.S.W.s but considerable variation in the number of outpatient visits to non-mental health specialists for behavioral health reasons. Increases in visits were not observed immediately after the storm but did occur three or four months later. This increase amounts to 430 extra visits for mental health across the 14 counties in December 1999 and almost 470 visits in January 2000, assuming approximately 10,000 Medicaid enrollees per county, the state average during that period. The increase in utilization over this two-month period is striking, and although we could not examine the reason for this, one can speculate about the clinical and environmental factors that may be responsible for this apparently delayed response to the storm. Utilization declined from this level in affected counties for the rest of the study period.

Although affected counties had fewer inpatient admissions with a behavioral health diagnosis than nonaffected counties, the monthly differences were seemingly random. In five of the months, the number of inpatient admissions was higher in the affected counties. December 1999 showed a very substantial decrease in the number of inpatient admissions in affected counties. Again assuming approximately 10,000 Medicaid enrollees per county, this finding amounts to 443 fewer visits in affected counties than in nonaffected counties for December 1999. Interestingly, this month also showed the largest difference between affected and nonaffected counties in the number of outpatient visits to non-mental health specialists. However, there were 30.68 more generalist visits in affected counties than in nonaffected counties. It is possible that there was a substitution effect, although our data cannot confirm this possibility.

Discussion and conclusions

The significant impact of Hurricane Floyd on the use of mental health services and spending on medications underscores the importance of planning for the implementation of human services after similar events. Although the Medicaid population may not be representative of the general population, our data were sufficiently rich to show that this group had long-run (12 months) average increases in the number of visits to psychologists, L.C.S.W.s, and nonspecialty providers and decreases in hospital admissions. The trends in monthly utilization for some types of services are far from linear, with peaks in utilization of generalist services noted three or four months after the disaster.

This finding is worthy of future research. The fact that the average number of visits to traditional mental health service providers remained virtually unchanged during the 12 months after the hurricane is striking. It is possible that facilities were closed, adversely affected, or inaccessible, which would have counterbalanced the increased demand for services with a reduction in the ability to supply those services. These causes cannot be separated out and evaluated from our data. However, the fact that we observed increases in the number of visits to psychologists, L.C.S.W.s, and non-mental health specialists in severely affected counties may indicate where the real mental health safety net lies. Whether the increased use of these other services spilled over to decreased behavioral health hospital admissions or whether the decrease was due to supply shocks or to increased opportunity costs resulting from disaster repairs or other related situations was not able to be determined from this analysis.

It should be noted that we report data on clinical visits associated with a behavioral health diagnosis. This approach is vastly different from that of an epidemiologic prevalence study, which would use a more objective measure of whether the visit was specifically for a mental health condition. An increase in our count of mental health visits could be due to an actual increase in the number of visits for mental health reasons or to an increase in the practice of recording mental health diagnoses without a true increase in the number of visits. If the practice of recording diagnoses after the hurricane varied by provider type, our results would have reflected this difference.

Despite the limited generalizability of this study to non-Medicaid populations, our results are consistent with current literature noting increased use of mental health services by persons with nonsevere mental illness after a natural disaster. Assuming that service delivery is uninterrupted by the disaster, some types of practitioners who provide mental health services should expect increased demand. Planners and policy makers may help meet this need by dispatching additional providers to affected areas and supplementing the supply of antianxiety and antidepressant medications to local pharmacies and facilities. However, there are also indications that demand may not increase—at least for certain types of services. We did not find a consistent pattern in service use, which, together with other studies, points to the difficulty in predicting service demand after a disaster. It is evident that in this and other studies many other unmeasured factors come into in determining how a population responds to extreme situations. This unpredictability speaks even more to the need to conduct monitoring and exercise diligence in the postdisaster period.

The results of this study in all likelihood underestimate mental health service use. In the days and months after the hurricane, federal and state governments, as well as a multitude of religious and other voluntary agencies, contributed substantially to the relief efforts in communities affected by Hurricane Floyd. Support was used for an array of purposes, including provision of mental health services. In select instances, relief aid was targeted directly at mental health services. For example, one month after the hurricane, the state of North Carolina received a grant of $868,670 specifically for mental health-related expenditures (18). More than half of this money, which was provided by FEMA in conjunction with the emergency services and disaster relief branch of the federal Center for Mental Health Services, was funneled directly into the 13 area mental health agencies that serve the entire area affected by the storm. The remainder was used for informational materials, training for local outreach staff, recovery-focused activities in schools, and direct outreach to families and particularly vulnerable populations. On a state level, the North Carolina Division of Aging allocated funds to five regional area agencies on aging for crisis counseling and outreach for older adults (18).

A multitude of other government and private voluntary agencies worked and provided aid in eastern North Carolina, including churches, the Salvation Army, Disabled American Veterans, hospitals, and universities. Although no direct accounting of mental health services provided by these agencies is available, on the basis of media reports and anecdotal evidence we suspect that they had an important impact. In the midst of a disaster recovery effort, it is also difficult to account for mental health "services" that may have been provided in the context of medical, law enforcement, religious, and an array of other services.

Although our findings show increased use of some services after the hurricane, the problem of unmet demand may have longer-lasting effects on rates of PTSD in communities located near these most severely affected counties (17). Wang and colleagues (7) note that the lack of significant postdisaster differences between severely affected and nonaffected communities may be due to increased rates of PTSD in areas not directly affected and the lack of attention given to first responders and health care providers in these communities.

A limitation of this study was our inability to determine the impact of other help-seeking behaviors. Affected individuals may have sought help from other sources, such as support groups, family members, and, as discussed earlier, through special government grants, religious organizations, or other providers not covered under the Medicaid program. Short-term outmigration of residents in the most severely affected areas also could not be captured in our data, although Domino and colleagues (16) explored permanent relocation as reflected in the county of residence reported in Medicaid administrative data and found no evidence of increased relocation from severely affected to other counties. Our data are insufficient to provide evidence of these behaviors or to refute their existence. Future studies should examine these other help-seeking behaviors.

Given our findings, psychiatrists and other mental health providers, as well as nonspecialist health practitioners, should be cognizant of the effects of disasters on their practice and possible changes in patient help-seeking behaviors in both the short and long term. The characteristically long lead time associated with the arrival of a hurricane may provide the time needed by emergency planners to prepare support structures to meet a variety of needs, including mental health needs. However, individual practitioners should be aware of the fluctuating effect on their caseload and demand for medications.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the financial support and assistance of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medical Assistance.

The authors are affiliated with the department of health policy and administration at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB 7411, Chapel Hill, North Carolina (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. County-level descriptive statistics on indicators of mental health care use per enrollee per month pre-Hurricane Floyd (July 1, 1998, to August 31, 1999), weighted by Medicaid enrollment in countya

aN=966, representing 69 counties each contributing 14 months of data; county averages are weighted by the number of Medicaid enrollees in each county and month.

|

Table 2. Regression results for average effect of the hurricane on mental health services use per enrollee per month in severe versus unaffected counties over the first year after the storm

|

Table 3. Predicted monthly changes in the number of visits in countiesa severely affected by Hurricane Floyd for the 12 months after the hurricane

aWith 10,000 Medicaid enrollees

1. Catalano RA, Kessell ER, McConnell W, et al: Psychiatric emergencies after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Psychiatric Services 55:163–166,2004Link, Google Scholar

2. Call JA, Pfefferbaum B: Lessons from the first two years of Project Heartland, Oklahoma's mental health response to the 1995 bombing. Psychiatric Services 50:953–955,1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Caldera T, Palma L, Penayo U, et al: Psychological impact of Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua in a one-year perspective. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:108–114,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McMurray L, Steiner W: Natural disasters and service delivery to individuals with severe mental illness—ice storm 1998. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 45:383–385,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Godleski LS, Luke KN, DiPreta JE, et al: Response of state hospital patients to Hurricane Iniki. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:931–933,1994Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kuo CJ, Tang HS, Tsay CJ, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among bereaved survivors of a disastrous earthquake in Taiwan. Psychiatric Services 54:249–251,2003Link, Google Scholar

7. Wang X, Gao L, Shinfuku N, et al: Longitudinal study of earthquake-related PTSD in a randomly selected community sample in North China. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1260–1266,2000Link, Google Scholar

8. Herring D: Hurricane Floyd's Lasting Legacy Assessing the Storm's Impact on the Carolina Coast. Available at http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/study/floydontroGoogle Scholar

9. Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, Najarian LM, et al: Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:911–916,2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Abrahams MJ, Price J, Whitlock FA, et al: The Brisbane floods, January 1974: their impact on health. Medical Journal of Australia 2:936–939,1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Carr VJ, Lewin TJ, Webster RA, et al: A synthesis of the findings from the Quake Impact Study: a two-year investigation of the psychosocial sequelae of the 1989 Newcastle earthquake. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:123–136,1997Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sacco L, Pessin N, Lindy D, et al: Learning from experience: a mental health response to the Northeaster of 1992. Caring 12(8):42–44,1993Google Scholar

13. Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, et al:60,000 disaster victims speak: I. an empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 65:207–239,2002Google Scholar

14. Rosenheck RA, Fontana A: Post-September 11 admission symptoms and treatment response among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services 54:1610–1617,2003Link, Google Scholar

15. Rosenheck RA, Fontana A: Use of mental health services by veterans with PTSD after the terrorist attacks of September 11. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1684–1690,2003Link, Google Scholar

16. Domino M, Fried B, Moon Y, et al: Disasters and the public health safety net: Hurricane Floyd hits the North Carolina Medicaid Program. American Journal of Public Health 93:1122–1127,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. FEMA Situation Report 8. Raleigh, NC, Federal Emergency Management Agency, 1999Google Scholar

18. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services: State receives mental health grant to help Hurricane Floyd victims. Press release, Oct 18, 1999. Available at www.dhhs.state.nc.us/pressrel/10–18–99.htmGoogle Scholar