Facial Emotion Recognition in Schizophrenia: Intensity Effects and Error Pattern

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors used color photographs of emotional and neutral expressions to investigate recognition patterns of five universal emotions in schizophrenia. METHOD: Twenty-eight stable outpatients with schizophrenia (19 men and nine women) and 61 healthy subjects (29 men and 32 women) completed an emotion discrimination test that presented mild and extreme intensities of happy, sad, angry, fearful, disgusted, and neutral faces, balanced for gender and ethnicity. Analyses evaluated accuracy of identifying emotions as a function of intensity, diagnosis, and gender of poser and rater. RESULTS: Patients performed worse than comparison subjects on recognition of all emotions and neutral faces combined, including mild and extreme expressions. For specific emotions, patients performed worse on recognition of fearful, disgusted, and neutral expressions. For all emotions except disgust, recognition of extreme intensity was better than recognition of mild intensity. However, patients showed less benefit from increased intensity for all emotions combined, and the difference was most pronounced for fear. Thus, patients were more impaired than healthy comparison subjects in identifying high-intensity expressions, even though this was an easier task than identifying low-intensity expressions. In the comparison of patterns of errors, patients and healthy subjects differed only in misattributions of neutral expressions; patients overattributed disgusted expressions and underattributed happy expressions. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with schizophrenia were impaired in overall emotion recognition, particularly fear and disgust, and did not benefit from increased emotional intensity. Error patterns indicate that patients misidentified neutral cues as negatively valenced.

Impaired recognition of facial affect in schizophrenia has been documented extensively (1, 2). Specifically, patients with first-episode schizophrenia performed worse than patients with affective psychosis and comparison subjects, particularly in recognition of fear and sadness (3). The question of whether emotion-processing performance is a differential deficit relative to cognitive performance has been debated (4, 5). Associations of measures related to emotion processing with illness have been reported, including duration (6, 7), symptoms (8–12), and social competence (6, 7).

The extent to which there is differential deficit in schizophrenia for processing specific emotions has not been clarified. Deficits in processing emotions may relate to dysfunction of mesial temporal regions, which has been documented in schizophrenia (13, 14). These regions are involved predominantly in fear recognition (15). There is some evidence that fear recognition is impaired in schizophrenia (3), but a specific deficit in fear recognition has not been demonstrated. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the recognition deficit relates to the intensity of the displayed facial expressions. Perhaps most importantly, many emotion recognition studies did not include neutral faces. False attribution of emotion to nonemotional faces has been the main deficit in depression (16) and may be of particular interest in schizophrenia, where neutral cues are frequently misidentified as unpleasant or threatening.

The most widely used facial stimuli for evaluating emotion recognition performance were created by Ekman and Friesen (17). They consist of facial expressions of universally recognized emotions, including happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise. This set of black and white photographs of posed emotions is restricted in ethnicity and age. However, a recent meta-analysis (18) reported that recognition is more accurate in people of the same ethnic group. Some studies employed a limited number of faces from the Ekman and Friesen set (3, 7, 8) with as few as 19 pictures representing six emotions. Other studies applied a larger number of stimuli from the University of Pennsylvania set (19), but with only happy, sad, and neutral expressions (9, 10, 12). In these studies, intensity of emotional expression was not specified or not evaluated because of the limited number of stimuli.

We have developed and validated a new set of three-dimensional color faces expressing five emotions (20). Out of this set, we constructed a 96-item test including low and high intensities of happy, sad, angry, fearful, and disgusted expressions, as well as neutral faces. (Of the six “universal” emotions [17], surprise was not included because its valence depends entirely on the triggering event and it can be any of the other emotions, with a rapid onset.) Using these faces in an fMRI study, we reported activation of the amygdala during emotion discrimination in healthy people (21) and attenuated amygdala response in patients with schizophrenia (22). These studies used faces from the same actors, but the tasks included differentiation of positive from negative emotions and age discrimination, rather than recognition of the target emotion. The aim was to evaluate differences in brain activation in patients with schizophrenia and healthy participants, who performed equally well on the simpler emotion processing task.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate recognition of a range of emotions and neutral expressions in schizophrenia. The study was designed to test the hypothesis of specific deficit in fear discrimination and establish the effect of intensity of facial expression. The number of stimuli and the inclusion of neutral expressions permitted analysis of error patterns for each emotion. We hypothesized that patients more commonly than healthy comparison subjects would attribute emotional valence to nonemotional faces and show error patterns that would less often include positive (happy) bias errors.

Method

Participants

The group studied consisted of 28 outpatients (19 men, nine women) and 61 healthy comparison subjects (29 men, 32 women) from the Schizophrenia Research Center of the University of Pennsylvania. Recruitment and assessment of participants followed established procedures (23, 24). After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects.

Patients underwent diagnostic examination with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (25) and met criteria for schizophrenia (N=26) or schizoaffective disorder, depressed type (N=2). Patients were clinically stable without prominent positive symptoms at the time of testing. All patients resided with family or lived independently. None had been hospitalized within 6 months, and 21 had not been hospitalized within 2 years of testing. Fifteen patients were in remission from acute symptoms, and the remaining 13 had residual symptoms. Assessment at the time of testing revealed low levels of positive (26), negative (27), depressive (28), and general psychiatric (29) symptoms (Table 1).

Healthy participants were recruited from the local community and underwent assessment (30) to screen for substance abuse as well as other psychiatric or medical illness that might affect brain function. Subjects with a family history of schizophrenia or affective illness were also excluded. Demographic characteristics of the patients and comparison subjects are shown in Table 2. Patients were older than the comparison subjects (t=7.30, df=87, p=0.001) and had a higher proportion of male subjects (67.9% versus 47.5%) (χ2=3.19, df=1, p=0.08).

Procedures

Participants were tested by a trained research assistant in a sound-attenuated room where facial stimuli were presented on a computer screen. Standard instructions were followed by a demonstration of tasks and practice. Details regarding acquisition of facial expressions and task construction have been described previously (20). Examples of facial stimuli are shown in Figure 1.

The Penn Emotion Recognition Test (31) is a computer-based test that includes 96 color photographs of facial expression of evoked—or felt—emotions: happy, sad, angry, fearful, disgusted, and nonemotional or neutral. There are eight low-intensity and eight high-intensity expressions of each emotion and 16 neutral expressions. Across emotional categories, stimuli are balanced for poser’s gender and ethnicity. There are 48 male and 48 female faces, 59 Caucasian faces, and 37 non-Caucasian (24 African American, five Asian, eight Hispanic) faces. Participants were asked to rate the emotional valence of each expression without time limit for responses. Average testing time for the entire task was 10–15 minutes for comparison subjects and 15–35 minutes for patients.

Data Analysis

Logistic regression was used to model the odds of correct recognition and how this changed across expression, intensity, patient status, race and gender of rater, and gender of poser. Separate analyses were performed for possible effects of gender and race on emotion recognition. Post hoc analyses of patient and comparison groups, limited to all subjects older than 19 years (28 patients and 31 comparison subjects) and subjects between 19 and 27 years of age (11 patients and 31 comparison subjects) at the time of testing, revealed no adverse effect of higher age or longer duration of illness. The logistic regression was fit by using generalized estimating equations (32) to account for the nonindependence or clustering of the multiple faces assessed by each observer. The comparisons are expressed in terms of odds ratios.

Differences in accuracy by diagnosis were examined as well as interactions of diagnosis and intensity. Gender and ethnicity of poser and rater were used as covariates. For the analysis of error patterns, confusion matrices (33) were generated for each emotion by response cell and classified by diagnosis, gender of poser and rater, and intensity. Goodness of fit analyses (34) were performed on these error rates to determine whether emotions selected were random when the rater was incorrect. A multinomial regression model was used to determine if the pattern of error rates differed by diagnosis. This approach was used instead of chi-square in order to account for the clustering within observers. The association between performance and clinical measures was evaluated by using Spearman correlation coefficients.

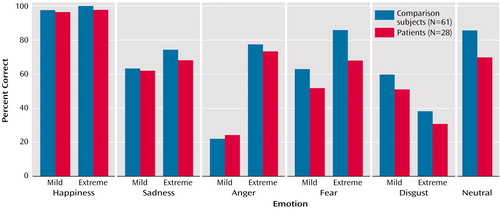

Results

As expected, patients performed worse than comparison subjects on emotion recognition across stimuli (patients got 63.6% correct, compared with 71.0% for comparison subjects) (odds ratio=0.71, p<0.001). Thus, patients were 0.71 times as likely to get the expression correct compared with healthy subjects. When examined by intensity, recognition rates were lower in patients than comparison subjects for both low-intensity (57.1% versus 61.1%) (odds ratio=0.84, p=0.04) and high-intensity (67.6% versus 74.9%) (odds ratio=0.70, p<0.001) expressions (Figure 2). With respect to specific emotions, recognition was worse in patients than in comparison subjects for fearful (60.0% versus 74.4%) (odds ratio=0.54, p=0.001), disgusted (40.9% versus 49.1%) (odds ratio=0.70, p=0.05), and neutral (69.6% versus 85.9%) (odds ratio=0.36, p<0.001) expressions but not for happy (97.1% versus 98.4%) (odds ratio=0.55, p=0.19), sad (65.2% versus 68.4%) (odds ratio=0.90, p=0.52) or angry (48.7% versus 49.9%) (odds ratio=0.92, p=0.48) expressions.

There were no independent effects of gender and race of rater on recognition of emotions in either group. Overall, female faces were better recognized (67.4% correct for male posers versus 69.9% for female posers) (odds ratio=0.89 for male posers relative to female posers, p=0.001). This difference was significant for happy (97.2% versus 98.7%) (odds ratio=0.44, p<0.05), sad (53.9% versus 80.3%) (odds ratio=0.29, p<0.001), and angry (44.7% versus 54.4%) (odds ratio=0.68, p<0.001) faces, but male faces were better recognized for fearful (76.4% versus 63.3%) (odds ratio=1.90, p<0.001) and neutral (83.6% versus 78.0%) (odds ratio=1.46, p=0.003) expressions. There was no difference in overall accuracy for rating faces of the same or different gender in either group, but disgusted faces were better recognized in same-gender photographs (49.3% correct for same gender versus 43.7% for different gender) (odds ratio=1.26 for same gender relative to different gender evaluations, p=0.01). Happy faces were better recognized in different-gender photographs (97.2% versus 98.7%) (odds ratio=0.44, p<0.05).

Recognition was better for high-intensity than low-intensity expressions for all emotions except disgust. However, across emotions patients showed less benefit from greater intensity of emotional expression (odds ratio=0.85 for patients relative to comparison subjects for mild expressions and odds ratio=0.70 for patients relative to comparison subjects for extreme expressions, p=0.02). The difference was most pronounced for fearful expressions (odds ratio=0.65 for mild and odds ratio=0.37 for extreme, p<0.03).

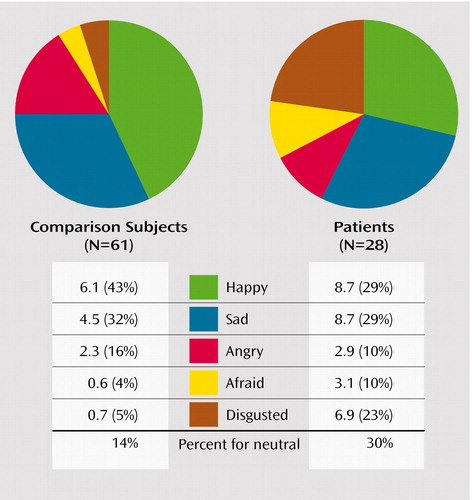

Examining the pattern of error rates, we found that patients and comparison subjects differed in the distribution of errors for neutral expressions (χ2=17.0, df=4, p=0.002) (Figure 3) but not for identification of happy, sad, fearful, angry, or disgusted expressions. Patients overattributed disgust to neutral expressions (23% for patients compared with 5% for healthy subjects) and, to a lesser extent, fearful expressions (10% versus 4%). Patients underattributed happy (29% versus 43%) and angry (10% versus 16%) expressions. In both groups, happy faces were most commonly misrecognized as neutral, followed by sad, then disgusted expressions. Sad faces were most commonly misrecognized as neutral, followed by disgusted, then angry expressions. Angry faces were most commonly misrecognized as neutral, followed by disgusted, then fearful expressions. Fearful faces were most commonly misrecognized as neutral, followed by disgusted, then sad expressions. Disgusted faces were most commonly misrecognized as sad, followed by angry, then fearful expressions.

The correlations between emotion recognition performance and symptom severity were significant for negative symptoms, including affective flattening (r=–0.57, p=0.002), alogia (r=–0.72, p<0.001), avolition (r=–0.49, p<0.02), and anhedonia (r=–0.47, p=0.02). Within emotions, fear recognition correlated with affective flattening (r=–0.47, p<0.02) and alogia (r=–0.55, p=0.006), sad recognition correlated with alogia (r=–0.52, p=0.009), and neutral recognition correlated with alogia (r=–0.42, p<0.04).

Discussion

Previous investigations have found impaired recognition of facial affect in schizophrenia. However, studies used a limited number of black and white photographs of Caucasian posers and tested heterogeneous patient groups. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate error patterns in facial recognition of five universal emotions in schizophrenia using color photographs of evoked low- and high-intensity emotional expressions and neutral expressions. This examination was enabled by the large number of stimuli for each emotion, balanced for intensity of expression, gender, and ethnicity of poser. These factors were not addressed in previous publications and may have contributed to the divergence of findings. Our study evaluated patients between the ages of 17 and 40 who were stable, had no prominent positive symptoms, and had not been hospitalized for at least 6 months. We replicated the finding of impaired emotion recognition, as measured by the overall recognition score, and extended it to show that patients with schizophrenia were impaired in recognition of mild emotional expressions and even more impaired on recognition of extreme expressions. All emotions, except disgust, were better recognized in the extreme than mild intensity. However, patients with schizophrenia did not benefit from greater emotional intensity to the extent that healthy subjects benefited. This relative lack of benefit was found for all emotions combined and was most pronounced for fear. This finding has practical implications in that more extreme facial expression of emotion may not lead to better recognition in patients with schizophrenia. More extreme expressions of emotions would lead to misattribution of other emotions rather than misidentification as neutral, which most commonly occurs in mild-intensity expressions. Perhaps most importantly, emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia showed some specific impairments. Recognition rates were lower for fearful, disgusted, and neutral expressions but not for happy, sad, and angry expressions.

Patients with schizophrenia differed not only in emotion recognition rates but also in the pattern of error rates, specifically for neutral faces. Neutral expressions were more commonly mistaken as sad or happy followed by disgusted in the schizophrenia group, and as happy followed by sad in the comparison group. Patients misidentified neutral cues as emotional, showing a negative bias. Previously we reported a positive error bias in schizophrenia (10, 35), but this was in the context of discriminating sad from happy emotions. Walker et al. (36) described a trend toward greater deficit in recognition of negative emotions in schizophrenia on a battery of eight different emotions, including five that are considered universally recognized. Error patterns of neutral faces were not examined separately in these studies.

As in previous studies, happy expressions were the best recognized of all emotions across groups. Happy expressions represent the only universally recognized positive emotion, in contrast to multiple negative emotions. We have observed little overlap in action units of facial expressions (37) for happy compared with sad, angry, and fearful expressions (31). The unique facial configuration of action units may explain the better recognition of happy expressions, even at low intensity.

The recognition deficit for fearful expressions was expected because mesial temporal lobe structures, implicated in fear processing, are affected in schizophrenia. We recently noted a lack of amygdala activation in patients with schizophrenia during discrimination of positive from negative emotions (22).

Disgust was not well recognized in either the comparison group or the patient group, but it was worse in patients. In contrast to the other emotions, disgust was better recognized in mild-intensity expressions and almost never identified as neutral. This finding lends support to the possibility that disgust is not a primary emotion but, rather, a combination of other emotions.

Impaired recognition of neutral or nonemotional faces in the schizophrenia group may have implications for understanding symptoms. During an acute psychotic episode, people with schizophrenia frequently misinterpret as significant neutral occurrences that are personally irrelevant. Perhaps even stable patients are more likely to identify neutral facial expressions as emotional, imputing negative valence to such expressions.

The lack of difference between groups for recognition of sad expressions accords with our previous finding that sad recognition is less impaired in schizophrenia (12, 35). However, the lack of deficit in recognition of anger in schizophrenia was less expected. On the basis of clinical symptoms, we expected that people who are more prone to paranoid thinking and hostility will also be more likely to misinterpret anger and show a different error pattern. Perhaps such deficits can be seen in study groups containing more paranoid patients.

Limitations of our study include the demographic differences between patients and the comparison group, the relatively small number of subjects in the patient group, and the focus on stable patients. The patient group was more likely to be male, non-Caucasian, and older than comparison subjects, although the difference was significant only for age. Because patients were clinically stable, most had undergone long-term treatment at our center and were older than the comparison group. However, there is no evidence that emotion recognition abilities change with age, and our statistical analyses indicated that neither age nor gender and race of rater accounted for the findings. The schizophrenia group was small because of the selection criteria for stability, which included partial or complete remission of positive symptoms and no hospitalization within the past 6 months. Comparisons regarding possible effects of typical or atypical antipsychotic medication on emotion recognition were not possible because only four patients were receiving typical antipsychotic medication only.

Another limitation of the study is that subjects were asked only to identify the emotion, not rate the intensity. In an earlier study (12), we used an emotion recognition test that investigated the ability to correctly identify the intensity of expression for happy and sad emotions using a forced choice design. Since the present test included 96 items, we were concerned that an additional task would produce fatigue in patients.

Finally, the high recognition rate for happy expressions in both patients and comparison subjects, which approached ceiling levels, may be unavoidable because happy is the only positive universal emotion. The majority of universally recognized emotions are of negative valence. Although surprise has been included as a positive emotion in some earlier studies, this is not necessarily valid because the valence of surprise depends on the triggering event. In our previous study examining emotion recognition (12), we evaluated outpatients who were considered stable enough for testing but not yet clinically stable. In that study, overall errors on the emotion recognition task were associated with greater severity of both negative and positive symptoms, including alogia, attention, hallucinations, and thought disorder. In the present study, the association with performance was found predominately for negative symptoms, probably because the positive symptoms were attenuated in this clinically stable group.

Future studies may examine the possible effect of treatment on emotion recognition abilities. A previous study (38) showed improved emotion recognition with amelioration of symptoms in acutely ill patients. This change was attributed to practice effects, despite a comparison group of patients with schizophrenia in remission who exhibited no such improvement. The emotion recognition test was limited by the use of only 12 faces representing six emotions. Few studies have explored the specificity of emotion recognition deficit to schizophrenia compared with other disorders, particularly bipolar disorder. A recent report (39) described impaired emotion recognition in patients with bipolar I disorder, specifically for fear and disgust. Finally, functional imaging studies using different emotional categories and contrasting groups with and without schizophrenia may establish the neural substrates of emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia.

|

|

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, Philadelphia, May 16–18, 2002. Received October 29, 2002; revision received May 27, 2003; accepted July 8, 2003. From the Neuropsychiatry Section, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kohler, Neuropsychiatry Section, 10 Gates Bldg., Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce St., Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-01839, MH-60722, MH-64045, and MO1-RR-0040.

Figure 1. Examples of Emotional Facial Expressionsa

aTop row: neutral and mild-intensity happy, sad, angry, fearful, disgusted expressions. Bottom row: neutral and extreme-intensity happy, sad, angry, fearful, disgusted expressions.

Figure 2. Recognition of Facial Emotions by Patients With Schizophrenia and Healthy Comparison Subjects

Figure 3. Error Profile of Patients With Schizophrenia and Healthy Comparison Subjects for Neutral Expressionsa

aFigure shows misidentification patterns of neutral faces as happy, sad, angry, fearful, or disgusted faces expressed in average frequencies and percentages of overall error rate. The overall error rate for identifying neutral expressions is also presented.

1. Morrison RL, Bellack AS, Mueser KT: Deficits in facial-affect recognition and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1988; 14:67–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mandal MK, Pandey R, Prasad AB: Facial expressions of emotions and schizophrenia: review. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:399–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Edwards J, Pattison PE, Jackson HJ, Wales RJ: Facial affect and affective prosody recognition in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001; 48:235–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kerr SL, Neale JM: Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:312–318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Salem JE, Kring AM, Kerr SL: More evidence for generalized poor performance in facial emotion perception in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1996; 105:480–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Silver H, Shlomo N, Turner T, Gur RC: Perception of happy and sad facial expressions in chronic schizophrenia: evidence for two evaluative systems. Schizophr Res 2002; 55:171–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mueser KT, Doonan R, Penn DL, Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS, Nishith P, DeLeon J: Emotion recognition and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1996; 105:271–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Penn DL, Combs DR, Ritchie M, Francis J, Cassisi J, Morris S, Townsend M: Emotion recognition in schizophrenia: further investigation of generalized versus specific deficit models. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:512–516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Mandal MK, Jain A, Haque-Nizamie S, Weiss U, Schneider F: Generality and specificity of emotion-recognition deficit in schizophrenic patients with positive and negative symptoms. Psychiatry Res 1999; 87:39–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schneider F, Gur RC, Gur RE, Shtasel DL: Emotional processing in schizophrenia: neurobehavioural probes in relation to psychopathology. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:67–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bryson G, Bell M, Lysaker P: Affect impairment in schizophrenia: a function of global impairment or a specific cognitive deficit. Psychiatry Res 1997; 71:105–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kohler CG, Bilker W, Hagendoorn M, Gur RE, Gur RC: Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:127–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gur RE, Turetsky BI, Cowell PE, Finkelman C, Maany V, Grossman RI, Arnold SE, Bilker WB, Gur RC: Temporolimbic volume reductions in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:769–775Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Nelson MD, Saykin AJ, Flashman LA, Riordan HJ: Hippocampal volume reduction in schizophrenia as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging: a meta-analytic study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:433–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Adolphs R, Tranel D, Hamann S, Young AW, Calder AJ, Phelps EA, Anderson A, Lee GP, Damasio AR: Recognition of facial emotion in nine individuals with bilateral amygdala damage. Neuropsychologia 1999; 37:1111–1117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Gur RC, Erwin RJ, Gur RE, Zwil AS, Heimberg C, Kraemer HC: Facial emotion discrimination, II: behavioral findings in depression. Psychiatry Res 1992; 42:241–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ekman P, Friesen WV: Unmasking the Face. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1975Google Scholar

18. Elfenbein HA, Ambady N: On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2002; 128:203–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Erwin RJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Skolnick B, Mawhinney-Hee M, Smailis J: Facial emotion discrimination, 1: task construction and behavioral findings in normal subjects. Psychiatry Res 1992; 42:231–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gur RC, Sara R, Hagendoorn M, Marom O, Hughett P, Macy L, Turner T, Bajcsy R, Posner A, Gur RE: A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J Neurosci Methods 2002; 115:137–143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Gur RC, Schroeder L, Turner T, McGrath C, Chan RM, Turetsky BI, Alsop D, Maldjian J, Gur RE: Brain activation during facial emotion processing. Neuroimage 2002; 16:651–662Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gur RE, McGrath C, Chan RM, Schroeder L, Turner T, Turetsky BI, Kohler C, Alsop D, Maldjian J, Ragland JD, Gur RC: An fMRI study of facial emotion processing in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1992–1999Link, Google Scholar

23. Gur RE, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, Levick S, Erwin R, Saykin AJ, Gur RC: Relations among clinical scales in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:472–478Link, Google Scholar

24. Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Richards J, Taleff MM, Heimberg C, Gallacher F, Gur RC: Volunteers for biomedical research: recruitment and screening of normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1022–1025Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

26. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

27. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

28. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

30. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP), version 2.0. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

31. Kohler CG, Turner TT, Gur RE, Gur RC: Recognition of facial emotions in neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Spectrums (in press)Google Scholar

32. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 73:13–22Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Kohavi R, Provost F: Glossary of terms: special issue on applications of machine learning and the knowledge discovery process. Machine Learning 1998; 30:271–274Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Agresti A: Categorical Data Analysis. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1990Google Scholar

35. Heimberg C, Gur RE, Erwin RJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RC: Facial emotion discrimination, III: behavioral findings in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1992; 42:253–265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Walker E, Marwit SJ, Emory E: A cross-sectional study of emotion recognition in schizophrenics. J Abnorm Psychol 1980; 3:428–436Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Ekman P, Friesen WV: Manual of the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978Google Scholar

38. Gaebel W, Wolwer W: Facial expression and emotional face recognition in schizophrenia and depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 242:46–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Lembke A, Ketter TA: Impaired recognition of facial emotion in mania. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:302–304Link, Google Scholar