Treatment Utilization by Patients With Personality Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Utilization of mental health treatment was compared in patients with personality disorders and patients with major depressive disorder without personality disorder. METHOD: Semistructured interviews were used to assess diagnosis and treatment history of 664 patients in four representative personality disorder groups—schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive—and in a comparison group of patients with major depressive disorder. RESULTS: Patients with personality disorders had more extensive histories of psychiatric outpatient, inpatient, and psychopharmacologic treatment than patients with major depressive disorder. Compared to the depression group, patients with borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely to have received every type of psychosocial treatment except self-help groups, and patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder reported greater utilization of individual psychotherapy. Patients with borderline personality disorder were also more likely to have used antianxiety, antidepressant, and mood stabilizer medications, and those with borderline or schizotypal personality disorder had a greater likelihood of having received antipsychotic medications. Patients with borderline personality disorder had received greater amounts of treatment, except for family/couples therapy and self-help, than the depressed patients and patients with other personality disorders. CONCLUSIONS: These results underscore the importance of considering personality disorders in diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric patients. Borderline and schizotypal personality disorder are associated with extensive use of mental health resources, and other, less severe personality disorders may not be addressed sufficiently in treatment planning. More work is needed to determine whether patients with personality disorders are receiving adequate and appropriate mental health treatments.

Ongoing concern in the United States over the cost and availability of mental health services has led to several major epidemiologic studies addressing treatment utilization among patients with axis I mental disorders (1–3). However, we know little empirically about the relationship of axis II personality disorders to treatment utilization. Personality disorders tend to be underdiagnosed in clinical settings (4–6), and their contributions to functional impairment and treatment are underappreciated despite the documented co-occurrence of personality disorders with other disorders (both axis I and axis II) (7, 8) and the negative effects of personality disorders on the treatment and course of axis I disorders (9–14).

Given these circumstances, clinicians have increasingly been challenged to develop treatment approaches that directly address personality disorder pathology. A growing body of literature supports the notion that effective psychosocial treatments are available for many patients suffering from personality disorders (9, 10). Although it has been established that patients with characterological problems typically take much longer to improve than those suffering from more acute axis I distress without character pathology (15–19), there is a paucity of knowledge about psychosocial treatments provided or received for patients with these axis II disorders.

As for psychiatric medications, there is some evidence that depressed mood, anger, and impulsivity in certain patients with borderline personality disorder respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants or mood stabilizers (20, 21). Some success has also been demonstrated for the use of antipsychotics for transient psychotic states and impulsivity in patients with borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder (22). Improvement in excessive social inhibition among patients with avoidant personality disorder was noted in a study using phenelzine and fluoxetine (23).

It has been well established that patients with borderline personality disorder are often difficult to treat because of the persistence and severity of their symptoms and because of the negative effects of the pathology on the treatment relationship. Several studies (20, 24–26) have examined treatment history patterns of patients with borderline personality disorder, and they have shown more frequent psychiatric hospitalizations, greater use of outpatient psychotherapy, more visits to emergency rooms, and worse implementation of treatment plans by hospital and clinic staff, as compared to groups with other personality disorders or axis I diagnoses.

Previous research has focused mainly on severe character pathology (i.e., borderline personality disorder), with few or no data on the comparative treatment utilization of patients with different forms and severity of personality disorders. Analyses have demonstrated significant differences in levels of adaptation and functioning among various axis II diagnostic groups (27 and personal communication from A. Skodol, 1999). Not surprisingly, impairment was more severe for patients with schizotypal personality disorder and those with borderline personality disorder than for patients with cluster C personality disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, who showed the least amount of difficulty. Because of such variations in functioning, we expected that treatment histories would differ between personality disorder groups.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the patterns of mental health treatment history among patients meeting criteria for at least one of four representative personality disorders—schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive—compared to patients with major depressive disorder without personality disorder. We hypothesized that the personality disorder groups would have greater past utilization of psychological/psychiatric treatments than the depressed comparison subjects. Previous findings regarding patients with borderline personality disorder suggested that this group would report more past psychiatric hospitalizations and greater use of day treatment and medication than either the group with avoidant personality disorder or the group with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Because schizotypal personality disorder is associated with severe impairment, we expected this group would also have a more extensive past psychiatric history than the groups with avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

Method

Subjects

Treatment-seeking patients aged 18 to 45 years were recruited from clinical services affiliated with each of the four sites in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Postings and media advertising were also used, targeting individuals who were seeking, were receiving, or had a recent history of psychiatric treatment or psychological counseling. Patients may have entered the study without any history of treatment, as they may have been seeking treatment or in the assessment phase of treatment when enrolled. Potential subjects were screened to exclude patients with active psychosis, acute substance intoxication or withdrawal, or a history of schizophrenia or of schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorder. The subjects were also screened for the possible presence of personality disorders or major depressive disorder without personality disorder, and subjects with positive screening findings were referred for complete diagnostic and treatment history assessment (see the following section). All eligible patients who began the assessment signed written informed consent statements after the research procedures had been fully explained.

The original study group comprised 668 patients, each assigned to one of five cells: schizotypal personality disorder (N=86), borderline personality disorder (N=175), avoidant personality disorder (N=157), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (N=153), or major depressive disorder (with no personality disorder) (N=97). Four patients did not give complete information on treatment history; thus, the analyses included 664 patients. The study group was 75% white, 12% African American, 9% Hispanic, and 2% Asian; 64% of the subjects were female, and their ages were evenly distributed from 18 to 45 years. A more detailed description of the study group, including the overview and rationale for the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, is available elsewhere (28).

Assessment

Treatment history was obtained at the baseline intake interview. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (29), the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (30), and the baseline version of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation Adapted for the Personality Disorders Study (31) were among the assessments conducted. All patients were interviewed by experienced master’s- or doctoral-level raters trained to adequate levels of diagnostic reliability (32) by using live or videotaped interviews under the supervision of trainers certified in use of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation and the senior author of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (M.C.Z.). The training for these two instruments was conducted at Brown University and at McLean Hospital, respectively.

The five diagnostic cells were determined by a priori criteria. Diagnoses of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder made with the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders were confirmed by either the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (33) or the Personality Assessment Form (34). For inclusion in the comparison group with major depressive disorder, patients had to meet fewer than 15 of the total criteria of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders and could not fulfill the features for any personality disorder diagnosis (i.e., had to be at least two criteria below threshold). It should be noted that there was considerable co-occurrence of axis I and axis II disorders (7). Two or more axis II disorders were found for 65% of the personality disorder patients, and 98% of the personality disorder patients met current or lifetime criteria for at least one axis I disorder.

Data on treatment utilization were obtained from the section on health care utilization in the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation Adapted for the Personality Disorders Study. Patients were interviewed about past psychosocial treatments: individual, group, and family or couples therapy; self-help groups; day treatment; psychiatric hospitalization; and half-way house residence. Estimates were obtained for the number of months that included two or more sessions of each outpatient treatment received during the patient’s lifetime and the total number of weeks of inpatient, halfway house, and day treatment received during the patient’s lifetime. Reports of current and past psychiatric medications used were also obtained. In the present analyses, medications were aggregated into five categories: antianxiety, hypnotic, mood stabilizer, antipsychotic, and antidepressant.

Data Analysis

We report the percentages and likelihood of patients having received the various psychosocial treatments and psychotropic medications during their lifetimes. General linear models from analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to compare the amounts of psychosocial treatment received across the groups. Differences among groups in the distribution of gender, age, race, and number of current and past comorbid axis I disorders have been reported elsewhere (7, 28).

In order to describe the unique contribution of personality disorder pathology to treatment utilization, we used logistic regression analyses. Race, gender, age, and number of lifetime axis I disorders were found to vary by cell assignment and to independently predict treatment utilization, and thus they were controlled for in the analyses. Because comorbid axis I pathology might be a characteristic of some or all of the personality disorders, we performed logistic regressions in two ways: controlling for axis I disorders (in addition to demographic variables) and not controlling for axis I disorders. Variables (cell assignment, demographic characteristics, axis I disorders) whose 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the odds ratios excluded 1.0 were retained. Each personality disorder cell, as well as the personality disorder cells combined, was compared to the depression comparison group in the examination of the likelihood of treatment received. Goodness-of-fit for the models was assessed by using Hosmer and Lemeshow’s C statistic (35). This was calculated by grouping cases according to deciles of the predicted probabilities and then comparing the expected number of events in each group with the number observed. The statistic is well approximated by the chi-square distribution with eight degrees of freedom. All analyses were conducted by using SAS version 6.12 (36).

Results

Likelihood of Treatment: Combined Personality Disorders Versus Depression

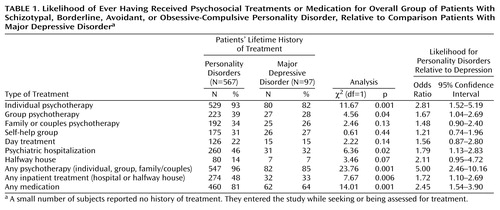

We found differences across study groups regarding the likelihood of having received the various forms of psychosocial treatment or psychotropic medication. The first analysis compared all personality disorder groups combined to the depression comparison group (Table 1). Outpatient psychotherapy (individual, group, or family/couples treatment) had been received by 96% of the personality disorder patients at some point in their lives, compared to 85% of the depressed comparison patients. Psychotropic medications had been received by 81% of the personality disorder patients in their lifetimes, compared to 64% of the comparison patients. When we examined specific types of psychosocial treatment, we found that significantly more personality disorder patients than depressed patients had received individual and group psychotherapy or had had psychiatric hospitalizations. There were no differences between the personality disorder and depression groups in utilization of family/couples therapy, self-help groups, or day treatment.

Likelihood of Treatment: Individual Personality Disorders Versus Depression

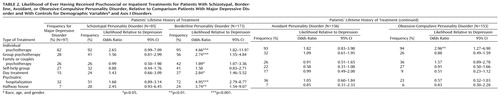

In the first set of logistic regression analyses, demographic variables (race, gender, and age) and number of lifetime axis I disorders were controlled. The individual diagnostic groups differed in the number of patients who had received most forms of psychosocial treatment (Table 2). Except for participation in self-help groups, the patients with borderline personality disorder had a greater likelihood of having received each mode of psychosocial treatment (i.e., individual, group, and family/couples therapy, day treatment, psychiatric hospitalization, and halfway house residence) than the patients with major depressive disorder. The significant odds ratios ranged from 1.89 (family/couples therapy) to 4.95 (hospitalization). The only other significant difference was the finding that patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were nearly three times as likely as depressed patients to have received individual psychotherapy.

Logistic regression analyses controlling for demographic variables alone yielded a pattern of findings similar to but stronger than those of the analyses controlling for demographic variables and comorbid axis I disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder had a greater likelihood of having received each mode of psychosocial treatment than the patients with major depressive disorder. The odds ratios ranged from 2.14 (family or couples therapy) (95% CI=1.23–3.71) to 6.19 (hospitalization) (95% CI=3.56–10.77). Patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were three times as likely as the comparison patients to have had individual psychotherapy (odds ratio=3.01, 95% CI=1.34–7.00). In addition, patients with schizotypal personality disorder were more likely to have had individual psychotherapy (odds ratio=2.79, 95% CI=1.07–7.28), psychiatric hospitalization (odds ratio=2.03, 95% CI=1.10–3.75), and halfway house treatment (odds ratio=2.93, 95% CI=1.14–9.45).

Logistic regression analyses for medication received across the patient’s lifetime indicated that patients with borderline personality disorder were more likely to have received all classes of drugs, except for hypnotics, than were patients with major depressive disorder (Table 3). The patients with borderline personality were twice as likely to have received antianxiety medications, over six times as likely to have received mood stabilizers, over 10 times as likely to have used antipsychotics, and twice as likely to have taken antidepressants. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder were over seven times as likely as depressed patients to have received antipsychotics over the course of their lives.

Controlling only for demographic variables, we also found that patients with borderline personality disorder were more likely than the depressed comparison patients to have received an antianxiety agent (odds ratio=3.09, 95% CI=1.75–5.42), mood stabilizer (odds ratio=7.59, 95% CI=3.71–15.48), antipsychotic (odds ratio=12.05, 95% CI=4.14–36.46), or antidepressant (odds ratio=3.03, 95% CI=1.69–5.31). Patients with schizotypal personality disorder were more likely to have received antipsychotics (odds ratio=8.12, 95% CI=2.64–24.78), antianxiety medications (odds ratio=2.33, 95% CI=1.21–4.44), and mood stabilizers (odds ratio=2.43, 95% CI=1.07–5.47). Finally, patients with avoidant personality disorder were slightly more likely than depressed patients to have taken antidepressants (odds ratio=1.94, 95% CI=1.11–3.35) and antipsychotics (odds ratio=3.22, 95% CI=1.06–9.78).

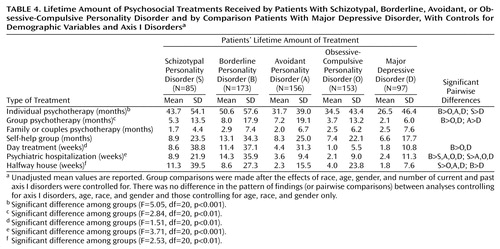

Amount of Psychosocial Treatment Received

The lifetime amounts of treatment received are found in Table 4. We report results from logistic regression analyses controlling for demographic variables and axis I disorders. Unadjusted means are presented. Differences between groups were evident in the amount of treatment received for most of the psychosocial treatments. The most consistent results were found for patients with borderline personality disorder, who had received significantly more treatment in all forms than the depression comparison group and the other personality disorder groups, with the exception of family/couples therapy and self-help. We also found differences for individual psychotherapy between schizotypal personality disorder and depression, for group psychotherapy between avoidant personality disorder and depression, and for psychiatric hospitalization and halfway house residence between schizotypal personality disorder and patients with avoidant personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and major depressive disorder.

Discussion

The results of this study show that patients with personality disorders have more extensive histories of psychiatric outpatient, inpatient, and psychopharmacologic treatment than do comparison patients with major depressive disorder. The patients with borderline personality disorder had a significantly greater chance of receiving every type of psychosocial treatment except self-help groups and were more likely to have used most classes of medications than were patients with major depressive disorder. The patients with borderline personality disorder had also received greater amounts of most psychosocial treatments than the comparison group and the other personality disorder groups. The patients with schizotypal personality disorder had a higher likelihood of having received antipsychotic medications than did the depressed patients, and they had had more psychiatric hospitalizations and halfway house stays than those with avoidant personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and major depressive disorder. A higher proportion of patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder reported a history of individual psychotherapy than did the depressed patients, and the patients with avoidant personality disorder had a larger amount of group therapy experience than the comparison group. Thus, it appears that patients with certain types of personality disorders seek treatments more often than those with major depressive disorder or other personality disorders and, in seeking treatments, also receive more of them.

These findings support our hypothesis that many patients with personality disorder pathology have more complicated and impairing symptoms and more enduring distress and disability, leading to more contact with the mental health system, than do psychiatric patients without personality disorders. In addition, axis I comorbidity is a significant factor contributing to the high proportions of patients with personality disorders who receive treatment and the greater amounts of treatment utilized. However, the fact that a number of these relationships largely do not change when axis I pathology is statistically held constant suggests that axis II disorders contribute to patient treatment seeking above and beyond the often comorbid presenting axis I problems.

Prior findings regarding utilization of treatment for borderline personality disorder were confirmed as well. The patients with borderline personality disorder used virtually every mode of psychosocial treatment more often and in greater amounts than the other groups. This finding is consistent with earlier reports of more frequent psychiatric hospitalizations and extensive, but sometimes erratic, use of outpatient mental health services (24–26, 37). The nature, severity, and varying phenomenology of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis continue to pose significant challenges to treating clinicians.

The current study has several limitations. First, the treatment data were obtained directly from patients, as opposed to examination of actual treatment records. While patients may vary in the accuracy of their reporting, our approach has been the standard method in prior studies (1–3). Another limitation may be that a history of seeking treatment was one major prerequisite for study participation. This could have implications for groups that are more averse to treatment or interpersonal interaction, such as individuals with schizotypal personality disorder, who under ordinary circumstances might be expected to seek treatment less frequently than our research subjects. In addition, the ethnic and gender composition of the study group may not be representative of the entire segment of the population who would meet the criteria for the target personality disorders. However, our study design was intended to yield findings meaningful within a clinical context.

An additional point regarding persons with schizotypal personality disorder is that 29% of those in our study also met the criteria for borderline personality disorder (7). Post hoc analyses removing patients with comorbid schizotypal and borderline personality disorder showed that those with schizotypal but not borderline personality disorder were no more likely than the patients with major depression to have received individual psychotherapy. This is consistent with what would be expected for individuals with more prototypical schizotypal personality disorder, and it helps to explain the greater use of individual psychotherapy by a certain portion of our subjects with schizotypal personality disorder.

The results of our study underscore the importance of considering personality disorder pathology in the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric patients. Certain personality disorders, such as borderline and schizotypal personality disorders, are related to more extensive use of mental health resources. On the other hand, the fact that patients with avoidant personality disorder are no more likely to receive treatment than are patients with major depressive disorder might suggest that no special consideration is being given to avoidant personality disorder psychopathology in treatment planning. While it is apparent that there is an additional public health burden associated with certain personality disorders, we do not yet have evidence that these patients are receiving adequate or appropriate treatment. Although patients with borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder have the most extensive treatment histories and a relatively high incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations, these same individuals continue to function at lower levels than patients with other personality disorders and those with no personality disorder (27). These trends continue in spite of increasing evidence (15, 38, 39) that the mental health system often fails to recognize the cost-effectiveness of appropriate psychotherapy for sicker patients, relying too heavily on more resource-intensive inpatient treatments. As we follow this patient group over time, the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study will continue to explore the relationship of treatment patterns to course and stability of axis II psychopathology.

|

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 152nd annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., May 15–20, 1999. Received Feb. 4, 2000; revision received July 26, 2000; accepted Sept. 6, 2000. From the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I.; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine and Yale Psychiatric Institute, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bender, Department of Personality Studies, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Box 129, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-50837, MH-50838, MH-50839, MH-50840, and MH-50850.

1. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, Kouzis AC, Frank RG, Edlund M, Leaf P: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:115–123Link, Google Scholar

2. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States, II: patterns of utilization. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1289–1294Google Scholar

3. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ: Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders: findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:95–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI: Differences between clinical and research practices in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1570–1574Google Scholar

5. Oldham JM, Skodol AE: Personality disorders in the public sector. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:481–487Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Kass F, Skodol AE, Charles E, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Scaled ratings of DSM-III personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:627–630Link, Google Scholar

7. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:256–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Widiger TA, Rogers JH: Prevalence and comorbidity of personality disorders. Psychiatr Annals 1989; 19:132–136Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH: Treatment outcome of personality disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43:237–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Target M: Outcome research on the psychosocial treatment of personality disorders. Bull Menninger Clin 1998; 62:215–230Medline, Google Scholar

11. Reich JH, Russell GV: Effect of personality disorders on the treatment outcome of axis I conditions: an update. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:475–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Shea MT, Widiger TA, Klein MH: Comorbidity of personality disorders and depression: implications for treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:857–868Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pilkonis PA, Frank E: Personality pathology in recurrent depression: nature, prevalence, and relationship to treatment response. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:435–441Link, Google Scholar

14. Pfohl B, Coryell W, Zimmerman M, Stangl D: Prognostic validity of self-report and interview measures of personality disorder in depressed inpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:468–472Medline, Google Scholar

15. Gabbard GO: Psychotherapy of personality disorders. J Practical Psychiatry & Behavioral Health 1997; 3:327–333Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Tyrer P, Seivewright H: Studies of outcome, in Personality Disorders: Diagnosis, Management and Course. Edited by Tyrer P. London, John Wright, 1988, pp 119–136Google Scholar

17. Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, Beutler LE: Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:1009–1016Google Scholar

18. Hogland P: Personality disorders and long-term outcome after brief dynamic psychotherapy. J Personal Disord 1993; 7:168–181Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Howard KI, Kopta SM, Krause MS, Orlinsky DE: The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. Am Psychol 1986; 41:159–164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Soloff PH: Symptom-oriented psychopharmacology for personality disorders. J Practical Psychiatry & Behavioral Health 1998; 4:3–11Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ: Biological and pharmacological aspects of borderline personality disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:1029–1033Google Scholar

22. Ewing SE, Falk WE, Otto MW: The recalcitrant patient: treating disorders of personality, in Challenges in Clinical Practice: Pharmacologic and Psychosocial Strategies. Edited by Pollack MH, Otto MW. New York, Guilford Press, 1996, pp 355–379Google Scholar

23. Deltito JA, Stam M: Psychopharmacologic treatment of avoidant personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:498–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Clarke M, Hafner RJ, Holme G: Borderline personality disorder: a challenge for mental health services. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1995; 29:409–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Perry JC, Cooper SH: Psychodynamics, symptoms, and outcome in borderline personality disorders and bipolar type II affective disorder, in The Borderline: Current Empirical Research. Edited by McGlashan TH. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1985, pp 19–41Google Scholar

26. Skodol AE, Buckley P, Charles E: Is there a characteristic pattern to the treatment history of clinic outpatients with borderline personality? J Nerv Ment Dis 1983; 171:405–410Google Scholar

27. Mehlum L, Friis S, Irion T, Johns S, Karterud S, Vaglum S: Personality disorders 2–5 years after treatment: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:72–77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Oldham JM, Keller MB: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:300–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

30. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L: Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Belmont, Mass, McLean Hospital, Laboratory for the Study of Adult Development, 1996Google Scholar

31. Keller M, Nielson E: Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation Adapted for the Personality Disorders Study. Providence, RI, Brown University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, 1989Google Scholar

32. Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender DS, Dolan RT, Sanislow CA, Schaefer E, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:291–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Clark LA: Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1993Google Scholar

34. Shea MT: Personality Assessment Form. Providence, RI, Brown University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, 1987Google Scholar

35. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Assessing the fit of the model, in Applied Logistic Regression. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989, pp 135–175Google Scholar

36. SAS Version 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

37. Andreoli A, Gressot G, Aapro N, Trico L, Gognalons MY: Personality disorders as a predictor of outcome. J Personal Disord 1989; 3:307–320Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Stevenson J, Meares R: An outcome study of psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:358–362Link, Google Scholar

39. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064Google Scholar