Brief Reports: Prospective Assessment of Treatment Use by Patients With Personality Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the utilization of mental health treatments over a three-year period among patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorders compared with patients with major depressive disorder and no personality disorder. METHODS: A prospective, longitudinal study design was used to measure treatment use for 633 individuals aged 18 to 45 years during a three-year period. RESULTS: Patients with borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely than those with major depressive disorder to use most types of treatment. Furthermore, all patients continued using high-intensity, low-duration treatments throughout the study period, whereas individual psychotherapy attendance declined significantly after one year. CONCLUSIONS: Although our data showed that patients with borderline personality disorder used more mental health services than those with major depressive disorder, many questions remain about the adequacy of the treatment received by all patients with personality disorders.

A previous retrospective study that examined the treatment history of 664 patients showed that more patients with personality disorders reported using outpatient, inpatient, and psychopharmacologic treatments compared with patients with major depressive disorder and no personality disorder (1). In addition, patients with borderline personality disorder reported receiving greater amounts of most treatments compared with those with depression and those with other types of personality disorders. However, use of mental health treatment has rarely been examined prospectively. One study that followed 362 patients for six years found that after the fourth year the use of intensive day and inpatient treatments declined among patients with borderline personality disorder and a mixed comparison group of patients with other personality disorders (2). Patients with borderline personality disorder continued to use significant amounts of outpatient psychotherapy and psychopharmacology sessions. The investigation reported here extended previous work by prospectively assessing a broader sample of patients with personality disorders—schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive—who were recruited from both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Methods

Treatment-seeking or recently treated patients aged 18 to 45 years were recruited from clinical services affiliated with each of the four sites in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS) and through media advertising. Patients were excluded from the study if they had active psychosis, acute substance intoxication or withdrawal, a history of schizophrenia, or a history of schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorders. A detailed description of the original sample, including the overview and rationale for the CLPS, is available elsewhere (3).

Diagnoses of personality disorders were determined at baseline with the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) (4). All patients were interviewed by experienced research clinicians who were trained to achieve adequate levels of diagnostic reliability (5).

Patients with major depressive disorder (the comparison group) were required to meet criteria for having a current major depressive episode according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (6), have less than 15 total criteria on the DIPD-IV, and not have features of any personality disorder diagnosis—that is, were at least two criteria below threshold. Eligible patients who began the assessment gave written informed consent after the research procedures had been fully explained. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of New York State Psychiatric Institute, McLean Hospital, and Brown University and by Yale School of Medicine's human investigation committee.

The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation Adapted for the Personality Disorders Study was used to assess treatment use for three periods: intake to 12 months, 13 to 24 months, and 25 to 36 months (7). Patients were recruited and followed for a three-year period from August 1996 through May 2001. For each interval, estimates were obtained for the number of sessions for each type of outpatient treatment, including individual therapy and medication consultations; the number of psychiatric emergency department visits and psychiatric hospitalizations; and the number of days hospitalized.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS, version 8 (8). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) methods (9) with a Poisson distribution were used to estimate the relationship of the treatment variables and the diagnostic categories over time. The GEE analyses, relying on the least restrictive assumption available, assumed that the correlations between the time points were unstructured. Because of differences between diagnostic groups at intake, ethnicity, gender, age, recruitment site, baseline level of functioning as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), and number of lifetime axis I and axis II disorders were controlled for in subsequent analyses.

Results

The intake sample was composed of 668 patients; 633 completed treatment assessments in the first year (84 patients with schizotypal personality disorder, 160 with borderline personality disorder, 150 with avoidant personality disorder, 148 with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and 91 with major depressive disorder). A total of 605 completed assessments in the second year (81 patients with schizotypal personality disorder, 155 with borderline personality disorder, 137 with avoidant personality disorder, 146 with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and 86 with major depressive disorder). A total of 578 completed the assessments in the third year (76 patients with schizotypal personality disorder, 146 with borderline personality disorder, 130 with avoidant personality disorder, 143 with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and 83 with major depressive disorder).

Among the 633 patients who provided treatment data at year 1, the mean±SD age was 33±8 years, 403 participants (64 percent) were female, and 485 (76 percent) were white.

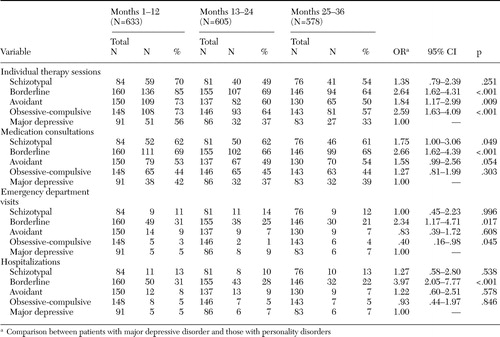

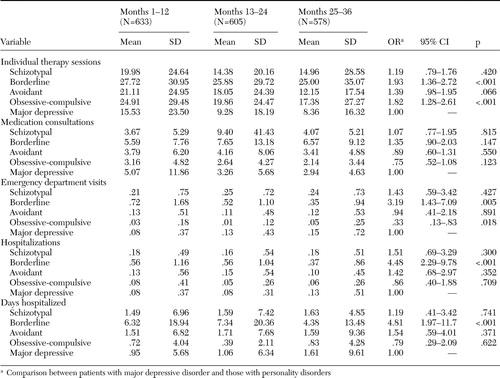

Table 1 presents the proportion of each group that received each type of treatment, and Table 2 shows the mean number of psychotherapy sessions, medication consultations, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and days hospitalized during each of the three intervals. The tables also summarize the results of the GEE analyses, which compared the likelihood of receiving treatment and the amount of treatment received between patients with personality disorders and those with major depressive disorder. A diagnosis-by-cell interaction effect was tested in all GEE analyses; no significant differences were found. This finding indicates that the patterns of use over time were the same for all five groups.

Results of the GEE analyses indicated that patients with borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorders were significantly more likely than those with major depressive disorder to receive individual therapy; odds ratios (ORs) ranged from 1.84 to 2.64.

In addition, compared with the first year of the study, a smaller proportion of patients in all diagnostic groups received individual therapy in the second year (OR=.49, p<.001) and in the third year (OR=.38, p<.001). However, this proportion remained constant over the second and third years of the study.

With regard to the amount of individual therapy used, patients with borderline personality disorder and those with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder received significantly more sessions compared with those with major depressive disorder. Compared with the first year, the amount of individual treatment received by all diagnostic groups was significantly less in the second year (OR=.84, p<.001) and the third year (OR=.73, p<.001), but amounts remained stable in years 2 and 3.

Patients with schizotypal personality disorder or borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely than patients with major depressive disorder to have had a medication consultation session during all three periods. Rates of receiving medication consultation sessions were relatively constant across all groups over the three years. Compared with patients with major depression, those with personality disorders did not receive significantly more medication consultation sessions, and the number of sessions received remained relatively constant throughout the study.

Compared with patients with major depressive disorder, those with borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely to make emergency department visits and be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were significantly less likely than those with major depressive disorder to have visited an emergency department. The proportion of each group that received services from an emergency department and a psychiatric hospital was constant for all groups throughout the study.

For the amount of hospital treatment received, compared with patients with major depressive disorder, those with borderline personality disorder had significantly more emergency department visits and psychiatric hospitalizations and more days in the hospital. Patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder had significantly fewer emergency department visits than those with major depressive disorder. The number of emergency department visits, psychiatric hospitalizations, and days in the hospital did not change significantly over time for any group.

Discussion

Similar to the findings of a previous retrospective study of lifetime treatment use (1), our results show that over a prospective three-year period, patients with borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely than those with major depressive disorder to have used more treatment resources of various types. In addition, the obsessive-compulsive group was significantly more likely than the major depressive disorder group to have received individual psychotherapy but less likely to have visited an emergency department. Compared with the major depressive disorder group, the avoidant group was more likely to have received individual treatment and the schizotypal group was more likely to receive psychiatric medications. These differences were significant beyond the contribution of comorbid disorders and demographic factors. When traced over time, the proportion of each group in individual psychotherapy declined after the first year, although the proportion of each group using other mental health services did not significantly change over the study period. These patterns were largely echoed in the analyses of the amount of treatment used by the groups over the three-year period.

These patterns of treatment use by patients with personality disorders have important implications. We found extensive use of more intensive treatments—emergency department visits and psychiatric hospital services—among patients with borderline personality disorder, which replicated the findings of other studies. These findings underscore the challenge that borderline personality disorder presents to the mental health field, even in less acute outpatient settings. Furthermore, our data raise questions about the adequacy of the duration and amount of individual psychotherapy received. The patients with personality disorders continued to show appreciable interpersonal and functional impairment two years after intake (10). Yet it can be seen that patients with borderline personality disorder received only about 25 sessions of individual psychotherapy per year—not even one session per week, on average—and more than 25 percent of patients with schizotypal, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder received no psychotherapy at all during the first year of the study. More data are needed to address whether appropriate outpatient therapy serves as the stabilizing factor leading to less use of more intensive services and less use of medical services in general.

Conclusions

We demonstrated, using a prospective study design, that patients with personality disorders and those with major depressive disorder and no personality disorder continued to use high-intensity, low-duration treatments throughout a three-year period, although use of individual psychotherapy declined significantly after the first year. In addition, although our data showed that patients with borderline personality disorder were heavier users of mental health services than those with major depressive disorder, many questions remain about the adequacy of the treatment received by all patients with personality disorders. Clearly, much more can be learned about factors affecting treatment use patterns among individuals with personality disorders. Future studies should focus on assessing needs for and barriers to treatment in this population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants MH-50837, MH-50838, MH-50839, MH-50840, and MH-50850 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Bender and Dr. Skodol are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Pagano, Dr. Dyck, Dr. Shea, and Dr. Yen are with the department of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr. Grilo, Dr. Sanislow, and Dr. McGlashan are with the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Zanarini and Dr. Gunderson are with McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

|

Table 1. Treatment patterns among patients with personality disorders and those with major depressive disorder

|

Table 2. Amount of annual treatment sessions used by patients with personality disorders and those with major depressive disorder

1. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al: Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:295–302,2001Link, Google Scholar

2. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al: Mental health service utilization of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:28–36,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, et al: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. Journal of Personality Disorders 14:300–315,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Zanarini, MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, et al: Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass, 1996Google Scholar

5. Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender DS, et al: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders 14:291–299,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

6. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition. New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1996Google Scholar

7. Keller M, Nielson E: Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation Adapted for the Personality Disorders Study. Providence, RI, Brown University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, 1989Google Scholar

8. SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute Inc, 1999Google Scholar

9. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 43:121–130,1986Google Scholar

10. Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, et al: Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychological Medicine 35:443–451,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar