Low Incidence of Persistent Tardive Dyskinesia in Elderly Patients With Dementia Treated With Risperidone

Abstract

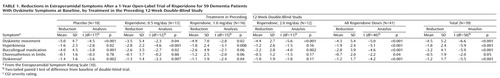

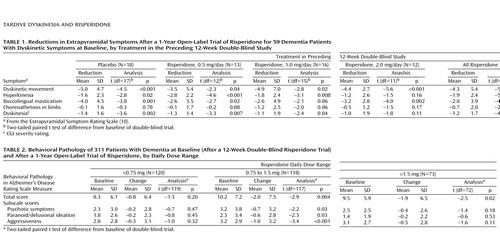

OBJECTIVE: The authors studied the incidence of tardive dyskinesia in elderly institutionalized patients with dementia being treated with risperidone.METHOD: After participating in a 12-week multicenter double-blind study during which they received placebo or one of three doses of risperidone, 330 patients (mean age=82.5 years) with Alzheimer’s, vascular, or mixed dementia were enrolled in a 1-year open-label study during which they received flexible doses of risperidone. Persistent emergent tardive dyskinesia was defined according to scores on the dyskinesia subscale of the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale.RESULTS: The mean modal risperidone dose was 0.96 mg/day (SD=0.53), and the median length of risperidone use was 273 days. The 1-year cumulative incidence of persistent emergent tardive dyskinesia among the 255 patients without dyskinesia at baseline was 2.6%. Patients with dyskinetic symptoms at baseline experienced significant reductions in the severity of dyskinesia. Patients who received 0.75–1.5 mg/day of risperidone showed a significant improvement in psychopathologic symptoms over the 1-year period.CONCLUSIONS: Although there was no control group, the observed incidence of persistent tardive dyskinesia with risperidone seemed to be much lower than that seen in elderly patients treated with conventional neuroleptics. The average optimal dose of risperidone in elderly dementia patients was found to be 0.75–1.5 mg/day.

Tardive dyskinesia is one of the most worrisome side effects associated with conventional neuroleptics, since it tends to persist and is sometimes irreversible (1, 2). Available data point to old age and cumulative neuroleptic amount as the most important risk factors for the emergence of tardive dyskinesia (2). Early extrapyramidal symptoms, alcohol or substance abuse, smoking, female gender, African American ethnicity, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorders, diabetes mellitus, and use of high-potency neuroleptics have also been identified as risk factors (3).

The cumulative incidence of tardive dyskinesia in prospectively studied young adult patients with chronic schizophrenia is estimated at 4%–5% per year (4). The rate is similar for younger, neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia patients in their first years of neuroleptic exposure, which indicates that long-term neuroleptic exposure at study entry is not a prerequisite. The incidence of tardive dyskinesia in older patients with little or no previous neuroleptic exposure is substantially higher. Jeste et al. (3, 5) reported a 1-year cumulative tardive dyskinesia incidence of 26% in 307 patients older than 45 years. Saltz et al. (6) and Woerner et al. (7) reported a 1-year cumulative incidence of 25% in 261 patients aged 55 and older.

In contrast, atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone may be associated with a lower incidence of tardive dyskinesia. Lemmens et al. (8) reported only two cases of tardive dyskinesia (0.2% per treatment year) in a review of 882 patients treated with risperidone for at least 12 weeks (903 patient years) in 27 clinical trials conducted by the manufacturer. It is, however, difficult to compute definitive incidence rates of tardive dyskinesia on the basis of such data given the vagaries of “patient treatment years.”

We present here the results of an open-label study of 330 elderly patients with dementia who received risperidone for up to 1 year. We assessed changes in psychopathologic symptoms, extrapyramidal symptoms, and tardive dyskinesia among patients treated with flexible doses of risperidone.

Method

The open-label study was preceded by a 12-week double-blind study (9) in which 625 elderly patients with Alzheimer’s, vascular, or mixed dementia received placebo or one of three doses of risperidone. Patients who completed the 12 weeks of double-blind treatment were eligible for a 1-year open-label investigation in which they received 0.5–2.0 mg/day of risperidone. They had to enter the open-label study within 14 days of completing the double-blind trial. For patients entering during the first 7 days, data obtained at the last visit of the double-blind trial served as the baseline data for the open-label trial; for those entering 8 to 14 days after completing the double-blind phase, new baseline assessments were performed. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each study site, and every patient and his/her family member or health care proxy gave written informed consent before participating.

The 330 patients who entered open-label treatment were examined every 2 months for 1 year. The Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (10) was used to assess extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. This scale measures the severity of parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and akathisia and has been employed in several studies of risperidone (11, 12). Each item in the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale is scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (absent) to 6 (severe and constant). The Functional Assessment Staging scale (13) was used to determine the dementia stage. Global cognitive functioning was assessed by using the Mini-Mental State (14). Psychotic and behavioral symptoms were evaluated by means of the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (15). Data on clinically observed adverse events were collected at each examination as were ECG, vital sign, and laboratory assessment results.

Dyskinesia at baseline of the double-blind trial was defined as a score of 3 points or higher on one item or 2 points or higher on two items of the Dyskinetic Movement Scale, a measure from the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale that assesses seven dyskinetic movements (lingual, jaw, buccolabial, truncal, choreoathetoid movements [for both upper and lower extremities], and other involuntary movements). Emergent tardive dyskinesia was defined as an increase from baseline of the double-blind trial of 3 points or higher on one item or 2 points or higher on two items of the seven-item Dyskinetic Movement Scale. Emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia was defined as emergent tardive dyskinesia that met the aforementioned severity criteria on two or more consecutive visits. These criteria for tardive dyskinesia are largely similar to the research diagnostic criteria that were based on the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (16). Worsened tardive dyskinesia in patients with symptoms of dyskinesia at baseline was defined according to Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale criteria similar to those for emergent tardive dyskinesia. Improvement in tardive dyskinesia was defined as that seen in patients whose dyskinesia scores decreased by the same magnitude and whose Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores never reached criteria for emergent or worsened persistent tardive dyskinesia. Time to emergence of persistent tardive dyskinesia was assessed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (17).

Results

Of the 435 patients who completed the 12-week double-blind trial, 330 (75.9%) elected to continue in open-label treatment with risperidone. The mean age of these 330 patients was 82.5 years (SD=7.5); 69.1% (N=228) were women, and 86.1% (N=284) were white. The dementia types diagnosed in this group were Alzheimer’s (76.1%, N=251), vascular (13.9%, N=46), and mixed (10.0%, N=33). The patients were characterized as having moderate to severe dementia with significant impairments in self-care (97.0% [N=320] were at dementia stage 6 or 7 per the Functional Assessment Staging scale). The mean Mini-Mental State score was 6.8 (SD=0.4). Continuous or intermittent neuroleptic medication had been received by 57.9% (N=191) of the patients during the 6 months preceding entry into the double-blind study. Background characteristics of the 330 patients in the open-label study were similar to those of the total cohort of 625 patients who entered the double-blind trial (9). Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores to diagnose tardive dyskinesia during the 1-year open-label study were available for 314 patients. Of these patients, 81.2% (N=255) did not meet criteria for dyskinesia at the baseline of the double-blind investigation while 18.8% (N=59) did.

The mean duration of treatment with risperidone was 230 days (SD=30); the median duration of treatment was 273 days. One hundred thirty-three patients (40.3%) completed 12 months of trial. The mean modal dose of risperidone was 0.96 mg/day (SD=0.53). Three patients (0.9%) received cholinesterase inhibitors, and 12 (3.6%) received anticholinergics.

Persistent Tardive Dyskinesia

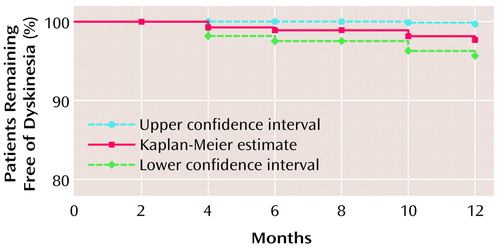

Among the 255 patients without symptoms of dyskinesia at baseline, six developed emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia during open-label treatment. The 1-year cumulative incidence of emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia was 2.6%; survival at 1 year was 97.4% (95% confidence interval=95.4%–99.5%) (Figure 1).

There was a significant relationship between risperidone dose during open-label treatment and the emergence of persistent tardive dyskinesia in the 255 patients without dyskinesia at baseline (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact probability test). Emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia was noted in four patients (5.5%) who received more than 1.5 mg/day of risperidone, in two patients (1.7%) who received 0.75–1.5 mg/day, and in none of the 120 patients who received less than 0.75 mg/day. Worsened tardive dyskinesia was noted in nine (15.3%) of the 59 patients with dyskinesia symptoms at baseline.

Patients who met the categorical criteria for persistent emergent, worsened, or improved tardive dyskinesia maintained their status at subsequent visits. Thus, the use of the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale cutoff scores described earlier to define persistent emergent or worsened dyskinesia appears to be a reliable method for detecting tardive dyskinesia. The use of a lower threshold (change of 1 point on two items or a change of 2 points on one item on two successive assessments) to define persistent tardive dyskinesia proved to be unstable, with patients’ status frequently changing from visit to visit.

Improvements in Dyskinesia

Of the 59 patients with dyskinesia at baseline of the double-blind trial, 29 (49.2%) showed persistent improvement. Overall, significant improvements were seen on all five dyskinesia factors (Table 1). In these 59 patients, no correlation was seen between change in dyskinesia score and change in parkinsonism score from baseline of the double-blind trial to endpoint of the open-label trial (r=0.12, df=57, p=0.34). There was also no correlation between change from baseline of the double-blind trial to worst dyskinesia rating during open-label phase and change in parkinsonism from baseline of double-blind to the visit with the worst dyskinesia rating (r=0.19, df=57, p=0.16). In the nine patients with dyskinesia at baseline whose dyskinesia worsened during open-label treatment, there was no relationship between worsening of dyskinesia and either risperidone dose or change in dose from double-blind to open-label phase.

Parkinsonism ratings were significantly higher at the endpoint of the open-label phase than at the baseline of either the open-label or the double-blind phase. Nine patients discontinued the open-label treatment because of extrapyramidal symptoms.

Psychosis and Behavioral Disturbances

Severity of psychotic and behavioral symptoms decreased during the open-label extension. Table 2 presents the changes in Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale total score and three subscale scores from the first visit of the open-label extension to the endpoint. Score reductions on each of the four measures were significant in patients who received 0.75–1.5 mg/day of risperidone.

Discussion

The cumulative annual incidence of emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia in the elderly patients with dementia in this study of risperidone was 2.6%. Although there was no comparison group of patients treated with typical neuroleptics, at least two other studies of relatively large samples of older patients have reported cumulative annual incidence rates of 25% or greater with conventional neuroleptics (5, 7). A direct comparison of results from different studies is problematic because of differences in patient populations as well as in methods used. Nonetheless, it would appear that the incidence of persistent tardive dyskinesia is considerably lower with risperidone than with typical neuroleptics.

The patient samples in the three studies were comparable in terms of ethnicity (82%–88% were white). The patients in the present study were somewhat older (mean age=82 years) than those reported in the investigations by Jeste et al. and Woerner et al. (mean ages of 66 and 73, respectively), and the gender distribution (69% women) in our study fell between that of the other two studies (18% and 74% women, respectively). All of the subjects in this report had a primary diagnosis of dementia, while this was true for 32% and 34% patients in the other two studies. The patients in the present investigation seemed to have had somewhat longer exposure to conventional neuroleptics at baseline (58% of patients during the previous 6 months) than the patients in the studies by Jeste et al. (57% of patients had fewer than 30 days’ exposure) or Woerner et al. (none had prior exposure). The 1-year cumulative incidence of tardive dyskinesia among the subgroup of patients with dementia from the Jeste et al. study was 25%. Mini-Mental State scores of the patients in the present report were substantially lower than those reported by Jeste et al. The samples from the three investigations were comparable in the rate of comorbid diabetes and concomitant anticholinergic use. Thus, there do not appear to be obvious population-related differences that would explain a lower risk of tardive dyskinesia with risperidone than with conventional neuroleptic treatment.

Whereas Jeste et al. (5) and Woerner et al. (7) used the AIMS (18) for the diagnosis of tardive dyskinesia, the present study used the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale. Although we employed an Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale cutoff score for diagnosing tardive dyskinesia that was numerically the same as that employed with the AIMS in the other two studies (at least one score of 3 or higher or two scores of 2 or higher), the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale has a broader range (0–6) of ratings for each item than the AIMS does (0–4). Hence, apparently similar scores on the two scales are not equivalent. Additionally, we used persistence of Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores on at least two consecutive examinations as the defining criterion for tardive dyskinesia in the present investigation. In order to clarify this definition explicitly, we have used the term “emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia.”

The rate of emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia in this study was too low to permit inferences regarding risk factors. It is unlikely that withdrawal of neuroleptics was a causal factor because, among patients without dyskinesia at baseline, all six cases of emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia occurred in patients who had received placebo in the double-blind trial or a higher dose of risperidone in the open-label period than in the double-blind trial.

The second important observation in this report is the substantial reduction in dyskinetic symptoms in the 59 patients who had dyskinesia at baseline of the double-blind trial. The rate of dyskinesia at baseline in our elderly patients is consistent with that in other reports (1, 2). It is conceivable that the symptom reduction with risperidone could have been secondary to discontinuation of previous (conventional) neuroleptic with a slow rate of spontaneous improvement. Nonetheless, this would suggest that risperidone did not contribute to persistence or increased severity of these symptoms during that period as might have occurred in at least some cases with a typical neuroleptic. The improvement in dyskinetic symptoms is unlikely to be due to suppression of symptoms by risperidone, since it was not related to dose of risperidone in the open-label period. Nor was the improvement greater in patients who had received placebo in the double-blind phase or who received a higher dose of risperidone in the open-label phase than in the double-blind study.

One limitation of the present study was that the raters were not blind to the medication that the patients were receiving. The findings reported above, however, are consistent with previous reports of low rates of emergent tardive dyskinesia with risperidone in schizophrenia patients (8) and resolution of dyskinetic symptoms with risperidone. Jeste et al. (19) found a significantly lower 9-month cumulative incidence of tardive dyskinesia in 61 middle-aged and elderly patients (mean age=66) prescribed risperidone than in a comparable group of 61 patients treated with haloperidol. Chouinard (20) reported greater reductions in preexisting tardive dyskinesia in patients who received risperidone than in those given placebo or haloperidol. Khan (21) reported substantial improvement of severe dyskinetic symptoms and behavioral improvement in a group of 21 mentally retarded adults who received risperidone after being treated with typical neuroleptics for many years.

Other atypical antipsychotics with combined serotonin/dopamine antagonism are also associated with less tardive dyskinesia than are typical neuroleptics. Lieberman et al. (22) noted improvement in tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia patients switched from typical neuroleptics to clozapine. A lower rate of tardive dyskinesia (based on the final two AIMS assessments) has been reported in schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine than with haloperidol (23).

The behavioral improvement observed in the patients with dementia would seem to outweigh the risks associated with the low rate of emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia. Patients treated with risperidone showed continued improvement in the open-label period beyond that observed in the 12-week double-blind trial. Improvements in the total Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale score as well as the psychosis and aggression subscales were observed in patients whose dose of risperidone was increased or unchanged during open-label treatment compared with that in the double-blind phase. It is also worth noting that although there was a significant increase in parkinsonian ratings on the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, only 3.6% of the patients needed treatment with an anticholinergic agent. The greatest improvement in psychopathologic symptoms was seen in patients treated with 0.75–1.5 mg/day of risperidone, which is consistent with the observations of the 12-week double-blind dose-ranging trial (9) as well as with the international multisite double-blind study of risperidone (24).

The low rate of emergent persistent tardive dyskinesia in this high-risk patient group suggests that risperidone is also likely to be associated with a low incidence of tardive dyskinesia in younger patients with chronic schizophrenia and other psychoses. This inference is supported by data demonstrating a low rate (0.2%) of emergent tardive dyskinesia in younger adults with schizophrenia treated with risperidone (8); a several-fold lower rate of emergent tardive dyskinesia with risperidone than with haloperidol in older patients, including some with little previous neuroleptic exposure (19); and improvement of preexisting tardive dyskinesia with risperidone (20).

Patterson et al. (25) have reported an association of tardive dyskinesia with lower quality of well-being among older patients treated with conventional neuroleptics. A substantially lower incidence of tardive dyskinesia with risperidone than with typical neuroleptics may result in improved quality of well-being and possibly in better treatment adherence, with a resultant increase in the proportion of patients who receive the needed treatment.

|

|

Received Jan. 19, 1999; revision received Dec. 13, 1999; accepted Dec. 20, 1999. From the Geriatric Psychiatry Intervention Research Center, University of California San Diego/VA San Diego Healthcare System; Janssen Pharmaceutica and Research Foundation; and Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Martinez, Janssen Pharmaceutica and Research Foundation, 1125 Trenton-Harbourton Rd., Titusville, NJ 08560; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by grants from Janssen Pharmaceutica to Drs. Jeste and Kane. The authors thank Drs. Daniel E. Casey, Donald C. Goff, Jeffrey A. Lieberman, Nina R. Schooler, and Carol A. Tamminga for their contributions during the analytic phase of this work.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve for Time to Emergence of Persistent Tardive Dyskinesia in 255 Dementia Patients Without Dyskinesia at Baseline During a 1-Year Open-Label Trial of Risperidone

1. American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report 18: Tardive Dyskinesia. Washington, DC, APA, 1980Google Scholar

2. Yassa R, Jeste DV: Gender differences in tardive dyskinesia: a critical review of the literature. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:701–715Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jeste DV, Caligiuri MP, Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Lacro JP, Harris MJ, Bailey A, Fell RL, McAdams LA: Risk of tardive dyskinesia in older patients: A prospective longitudinal study of 266 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:756–765Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kane JM, Woerner M, Lieberman JA, Kinon BJ: Tardive dyskinesia and drugs, in New Approaches to the Development of Anti-Schizophrenic Drugs: Proceedings of a Symposium (Drug Development Research Series, vol 9). Edited by Cornfeldt ML, Shutske GM. New York, Alan R Liss, 1986, pp 41–51Google Scholar

5. Jeste DV, Lacro JP, Palmer B, Rockwell E, Harris MJ, Caligiuri MP: Incidence of tardive dyskinesia in early stages of low-dose treatment with typical neuroleptics in older patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:309–311Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Saltz BL, Woerner MG, Kane JM, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Bergmann KJ, Blank K, Koblenzer J, Kahaner K: Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia incidence in the elderly. JAMA 1991; 266:2402–2406Google Scholar

7. Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, Saltz BL, Lieberman JA, Kane JM: Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia in the elderly: rates and risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1521–1528Google Scholar

8. Lemmens P, Brecher M, Van Baelen B: A combined analysis of double-blind studies with risperidone versus placebo and other antipsychotic agents: factors associated with extrapyramidal symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:160–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Katz IR, Jeste DV, Mintzer JE, Clyde C, Napolitano J, Brecher M: Comparison of risperidone and placebo for psychosis and behavioral disturbances associated with dementia: a randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:107–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annable L, Jones BD: Extrapyramidal symptom rating scale (letter). Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7:233Google Scholar

11. Simpson GM, Lindenmayer JP: Extrapyramidal symptoms in patients treated with risperidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:194–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Peuskens J (Risperidone Study Group): Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multi-national, multi-centre, double-blind, parallel-group study versus haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:712–726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Reisberg B: Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:653–659Medline, Google Scholar

14. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris S, Franssen E, Georgotas A: Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:9–15Medline, Google Scholar

16. Schooler NR, Kane JM: Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:486–487Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Assoc 1958; 53:457–481Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 534–537Google Scholar

19. Jeste DV, Lacro JP, Nguyen HA, Petersen ME, Rockwell E, Sewell DD, Caligiuri MP: Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with risperidone versus haloperidol. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:716–719Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Chouinard G: Effects of risperidone in tardive dyskinesia: an analysis of the Canadian multicenter risperidone study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15(Feb suppl 1):36S–44SGoogle Scholar

21. Khan BU: Risperidone for severely disturbed behavior and tardive dyskinesia in developmentally disabled adults. J Autism Dev Disord 1997; 27:479–489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, Pollack S, Borenstein M, Kane J: The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158:503–510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tamura RN, Tran PV, Potvin JH: Blind, controlled, long-term study of the comparative incidence of treatment-emergent tardive dyskinesia with olanzapine or haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1248–1254Google Scholar

24. De Deyn P, Rabheru K, Rasmussen A, Bocksberger JP, Dautzenberg PLJ, Eriksson S, Lawlor BA: A randomized trial of risperidone, placebo, and haloperidol for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Neurology 1999; 53:946–955Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Patterson TL, Kaplan RM, Grant I, Semple SJ, Moscona S, Koch WL, Harris MJ, Jeste DV: Quality of well-being in late-life psychosis. Psychiatry Res 1996; 63:169–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar