Use of Self-Ratings in the Assessment of Symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this research was to determine if adults can provide a true rating of their own childhood and current symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).METHOD: The authors conducted two studies. In study 1, 50 adult subjects completed a questionnaire assessing their ADHD symptoms in childhood. In addition, a parent of each subject completed a questionnaire rating the subject’s childhood ADHD symptoms. In study 2, 100 adult subjects completed a questionnaire rating their own current ADHD symptoms. The subject’s partner also completed a questionnaire rating the subject’s current ADHD symptoms. The correlation between subject and observer ratings was measured in each study. Inattentive symptoms, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and total symptoms were analyzed.RESULTS: Good correlations were found between subject and observer scores in both studies.CONCLUSIONS: The diagnosis of ADHD in adults relies on an accurate recall of childhood behavior and an accurate account of current behavior. The results of this study suggest that adults can give a true account of their childhood and current symptoms of ADHD.

At one time, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was considered strictly a childhood condition, outgrown in adolescence and of little consequence for adult mental health. Research indicates, however, that the disorder persists into adulthood in 30%–70% of affected individuals (1–3), often with serious consequences. ADHD is a known risk factor among adults for antisocial behavior, substance abuse, academic underachievement, and low occupational success (1, 4–7).

Although DSM-IV permits the diagnosis of ADHD in adults, assessment is considered problematic. To diagnose ADHD in an adult, it must be established that the individual currently meets criteria for the disorder and that clinically significant symptoms date from childhood. Because it is not always practical, or possible, to obtain information from an informant such as a parent or employer, clinicians and researchers often must rely on the subject’s own account of his or her current symptoms and the subject’s recollection of childhood symptoms in making a diagnosis. Since there is some question regarding the accuracy of self-reports (8, 9) and retrospective information (6, 8–11), assessing adults for ADHD is a contentious issue. To further research in adult ADHD, it is necessary to determine if adults can accurately report on current symptoms and accurately recall childhood symptoms. We conducted two studies to examine the validity of self-reported symptoms of ADHD, using informant ratings as the “gold standard.”

Method

Research Design

Study 1 examined the validity of childhood recollections of ADHD behavior. Fifty adult subjects completed a questionnaire rating their childhood ADHD symptoms. A parent of each subject also completed a similar questionnaire rating the subject’s childhood ADHD symptoms. The subject was given his or her choice about which parent, mother or father, would complete the questionnaire. Subjects and parents were asked to fill out the questionnaires completely and to the best of their ability. Two incomplete questionnaires, filled out by parents, were discarded.

In study 2, 100 adult subjects completed a questionnaire rating their current ADHD symptoms. The partner (spouse or common-law) of each subject completed a similar questionnaire rating the subject’s current ADHD symptoms. Participants in the study were instructed to fill in the questionnaire completely and to the best of their ability. Nine questionnaires were handed in incomplete and were discarded.

Subjects

Subjects were volunteers recruited from among the parents of children undergoing assessment at The Hospital for Sick Children, staff of the hospital, and friends and relatives of individuals working at the hospital. Although the subjects were not assessed for ADHD, a wide range of scores was obtained in both studies, indicating that a portion of the subjects rated themselves as having a considerable number of symptoms associated with ADHD. Questionnaires were completed by the participants after the study had been explained to them, and written informed consent was obtained.

The subjects in study 1 ranged in age from 20 to 50 years. The parents ranged in age from 45 to 93. Subjects included 28 women and 22 men. Forty-three mothers and seven fathers provided the parental ratings. There were 23 daughter and mother pairs, five daughter and father pairs, 20 son and mother pairs, and two son and father pairs.

The subjects in study 2 ranged in age from 25 to 65 years. The partners ranged in age from 25 to 65 years. Forty-seven female subjects and their male partners participated; 53 male subjects and their female partners participated.

Instruments

The instruments used in this study are based on the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. All 18 items included in DSM-IV were included in the questionnaire. Inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were intermixed. A rating scale ranging from 0 to 3 was used to determine the incidence of each ADHD symptom in an individual. On this scale, symptoms are rated as exhibited by the subject never (or rarely) (score=0), sometimes (score=1), often (score=2), or usually (score=3). A total score including inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms was obtained. In addition, separate scores were obtained for inattentive and hyperactive symptoms. The highest total score obtainable was 54. The highest score obtainable for inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms was 27. The diagnostic criteria listed in DSM-IV were adapted slightly for use with adults. The references to school, schoolwork, homework, and toys were omitted.

The use of questionnaires based on DSM-IV criteria for ADHD is not unique to the present research. Similar questionnaires have been used in other studies (12). This research is unique in that it compared subject and informant ratings of ADHD symptoms. The questionnaires used in the present study have not been validated as diagnostic instruments.

Statistical Analysis

In both studies, the correlation between subject and informant ratings for inattentive symptoms, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and total symptoms was measured by means of the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. To determine if the subjects and participants viewed the severity of symptoms differently, the mean subject and observer score for each of these categories was measured by using t tests for paired samples.

There was a large age range in study 1. To determine if the subjects’ ages at the time of testing affected the size of the correlation, the subjects were divided into two groups on the basis of the mean subject age of 33.76. One group included 25 subjects 34 years old or older, and the other included 25 subjects younger than 34. We used the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient to determine the correlations between subjects and informants for inattentive symptoms, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and total symptoms in these two groups.

The effect of subjects’ ages on the size of the correlation was also examined in study 2. These subjects were divided into two groups on the basis of the mean subject age at the time of testing of 39.12. One group included 48 subjects 40 years old or older, and the other included 52 subjects younger than 40. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the correlations between subjects and informants for inattentive symptoms, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and total symptoms in these two groups.

Results

Study 1

For subject and observer ratings, all correlations were found to be statistically significant. The correlations obtained for inattentive symptoms, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and total symptoms were r=0.76, df=48, pγ<0.001; r=0.69, df=48, pγ<0.001; and r=0.79, df=48, pγ<0.001, respectively.

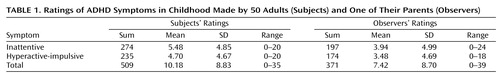

The t tests comparing the means of the subject and observer scores (Table 1) were also statistically significant. The values obtained were inattentive symptoms, t=3.21, df=49, p=0.002; hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, t=2.36, df=49, p=0.022; and total symptoms, t=3.40, df=49, p=0.001.

For the analysis of age effects, although differing slightly, all correlations were found to be statistically significant. The following correlations were found for the subjects who were 34 years old or older: inattentive symptoms, r=0.68, df=23, pγ<0.001; hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, r=0.70, df=23, pγ<0.001: and total symptoms, r=0.77, df=23, pγ<0.001. The correlations for the subjects who were younger than 34 were r=0.85, df=23, pγ<0.001, for inattentive symptoms; r=0.75, df=23, pγ<0.001, for hyperactive-impulsive symptoms; and r=0.83, df=23, pγ<0.001, for total symptoms.

Study 2

In the analysis of subject and observer ratings, the correlations between subject and observer scores for inattentive symptoms, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and total symptoms were statistically significant. The correlations obtained were as follows: inattentive symptoms, r=0.70, df=98, pγ<0.001; hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, r=0.59, df=98, p≤0.001, and total symptoms, r=0.69, df=98, p≤0.001.

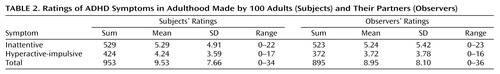

The values obtained from the t tests comparing the means of the subject and observer scores for the three categories (Table 2) were not statistically significant. The results were as follows: inattentive symptoms, t=0.13, df=99, p=0.90; hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, t=1.56, df=99, p=0.12; and total symptoms, t=0.92, df=99, p=0.36.

In the analysis of age effects, correlations for all categories were found to be statistically significant. The values obtained for the subjects who were 40 years old or older were as follows: inattentive symptoms r=0.74, df=46, pγ<0.001; hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, r=0.65, df=46, pγ<0.001; total symptoms, r=0.75, df=46, pγ<0.001. The correlations found for the subjects who were younger than 40 were r=0.65, df=50, pγ<0.001, for inattentive symptoms; r=0.54, df=50, pγ<0.001, for hyperactive-impulsive symptoms; and r=0.63, df=50, pγ<0.001, for total symptoms.

Conclusions

The present research investigated the ability of people to rate their own childhood and current behavior. The results show a good correlation between subjects’ and informants’ ratings. There are a number of issues that must be addressed, however.

Information obtained retrospectively is often viewed with suspicion (8, 11, 13, 14). Retrospective self-reports of childhood ADHD symptoms are seen as particularly suspect (6, 8–11). Indeed, individuals do not always report their own histories accurately (15, 16). It has been reported that adults and adolescents do not provide valid information on their own childhood symptoms of ADHD (6, 10, 11). Research demonstrates, however, that the type of information an informant is asked to recall (15, 16) and the manner in which the questions are posed can affect the accuracy of recall (17). More specific questions elicit more accurate responses than do open-ended questions. The responses to specific questions have been shown to have a high accuracy (17). The questionnaires used in the present research contain reasonably specific statements regarding past and present behavior.

There is also some concern about current information obtained from adults being assessed for ADHD. Data about an individual obtained from an informant is often considered to be more accurate than information obtained from the individual (8, 9). In many cases, however, there is no other person who may knowledgeably comment on the behavior of a person being assessed for ADHD. A spouse or other partner is often not available. Adults being assessed for ADHD may not want an employer involved in the assessment process. It is generally necessary to rely on the statements of the individual being assessed. Research does indicate that self-reports can be valid. Studies have found accurate reporting of substance abuse (18) and smoking (19), two socially unacceptable behaviors.

The possibility that the accuracy of recall of ADHD symptoms decreases with time was tested. Also tested was the possibility that age colors the perception of ADHD symptoms. In the present research, age did not seem to be a significant factor in recall of childhood behavior or judgment of current behavior.

Subjects tended to rate themselves as having more symptoms, or more intense symptoms, than did the informants. This difference reached significance in the study of childhood symptoms. This finding is not unique. Researchers investigating the reliability and validity of self-ratings of symptoms associated with other types of psychiatric disorders have obtained similar results (20, 21).

The subject and informant scores obtained on the questionnaires used in this research correlate substantially. This finding demonstrates that the information obtained from an individual about his or her behavior is as accurate as that obtained from a knowledgeable informant. The fact that subjects’ and informants’ ratings were highly correlated suggest that the ratings were valid.

It is impossible to say which participant gave the more accurate assessment on those occasions when the subject and observer did not agree. Many of the symptoms of ADHD as described by DSM-IV are subjective, however. An example of this would be feelings of restlessness. It is likely that a subject would be better able to describe this behavior than would an informant. When describing past behavior in the classroom, it is likely that the subject has better knowledge of events than the informant. Minor transgressions occurring in school, remembered by the subject, may have gone unreported to the parent. Regarding adult behavior, a subject may not inform a spouse about all the difficulties encountered at work. The subject would again be better able to provide a complete and accurate account of his or her own behavior.

A wide range of scores was obtained in both of our studies. Although some subjects reported experiencing no ADHD symptoms at all, the study group included subjects who rated themselves as having a considerable number of ADHD symptoms. It is a limitation of the study that the subjects were not assessed for ADHD, however.

The results of this study suggest that adults can give a true account of their childhood and current behavior. This finding has important implications for the study of ADHD. It can be concluded that if an informant is not available, an assessment of symptoms of ADHD can be made on the basis of subjects’ accounts of their own behavior. It should perhaps be noted that the fact of having a child with ADHD does not affect adults’ reporting of their own ADHD symptoms (22).

|

|

Received Jan. 29, 1999; revisions received July 30 and Nov. 1, 1999; accepted Nov. 18, 1999. From the Institute of Medical Science, University of Toronto, Toronto; and The Hospital for Sick Children, Department of Psychiatry, Brain and Behavior Programme. Address reprint requests to Dr. Schachar, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Ave., Toronto, Ont., Canada, M5G 1X8; pattyannemurphy @hotmail.com (e-mail). Supported by grant MT-13131 from the Medical Research Council of Canada.

1. Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T: Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: a controlled prospective 15-year follow-up of 63 hyperactive children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1985; 24:211–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N: Hyperactive boys almost grown up, I: psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:937–947Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bonagura N, Malloy TL, Addali KA: Hyperactive boys almost grown up, V: replication of psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:77–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Knee D, Munir K: Retrospective assessment of DSM-III attention deficit disorder in nonreferred individuals. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:102–106Medline, Google Scholar

5. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens T, Norman D, Lapey KA, Mick E, Lehman BK, Doyle A: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1792–1798Google Scholar

6. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Milberger S, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV: Psychoactive substance use disorders in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1652–1658Google Scholar

8. Mannuzza S, Gittelman R: Informant variance in the diagnostic assessment of hyperactive children as young adults, in Mental Disorders in the Community: Progress and Challenge: Proceedings of the American Psychopathological Association, vol 42. Edited by Barrett JE, Rose RM. New York, Guilford, 1985, pp 243–254Google Scholar

9. Shaffer D: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:634–639Google Scholar

10. Wender PH, Reimherr FW, Wood DR: Attention deficit disorder (“minimal brain dysfunction”) in adults: a replication study of diagnosis and drug treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:449–456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW: The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:885–890Link, Google Scholar

12. Murphy K, Barkley RA: Prevalence of DSM-IV symptoms in adult licensed drivers: implications for clinical diagnosis. J Attention Disorders 1996; 1:147–161Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Chess S, Thomas A, Birch HG: Distortions in developmental reporting made by parents of behaviorally disturbed children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1966; 5:226–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Steele GP, Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P: The reliability of reporting adverse experiences. Psychol Med 1980; 10:301–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Tilley BC, Barnes AB, Bergstralh E, Labarthe D, Noller KL, Colton T, Adam E: A comparison of pregnancy history recall and medical records: implications for retrospective studies. Am J Epidemiol 1985; 121:269–281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Olson JE, Shu XO, Ross JA, Pendergrass T, Robison LL: Medical record validation of maternally reported birth characteristics and pregnancy-related events: a report from the children’s cancer group. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145:58–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Mitchell AA, Cottler LB, Shapiro S: Effect of questionnaire design on recall of drug exposure in pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 123:670–676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Weiss RD, Najavits LM, Greenfield SF, Soto JA, Shaw SR, Wyner D: Validity of substance use self-reports in dually diagnosed outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:127–128Link, Google Scholar

19. Wills TA, Cleary SD: The validity of self-reports of smoking: analyses by race/ethnicity in a school sample of urban adolescents. Am J Public Health 1997; 87:56–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Tryer P, Alexander MS, Cicchetti D, Cohen MS, Remington M: Reliability of a schedule for rating personality disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 135:168–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR: Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:610–619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E: Symptom reports by adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: are they influenced by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in their children? J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:583–584Google Scholar