Lower Effectiveness of Divalproex Versus Valproic Acid in a Prospective, Quasi-Experimental Clinical Trial Involving 9,260 Psychiatric Admissions

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined clinical differences between divalproex sodium and generic immediate-release valproic acid. METHOD: This 6-year prospective, quasi-experimental clinical trial compared the effectiveness and tolerability of divalproex and valproic acid. The dependent variables were length of hospital stay, rehospitalization rate, and adverse drug reactions in 9,260 psychiatric admissions. RESULTS: Inpatients who initially received divalproex sodium had a 32.7% longer hospital stay and 3.8% higher readmission rate than did patients who initially received valproic acid. Initial treatment with divalproex prolonged length of stay by 30.3% in patients treated with divalproex and valproic acid during different admissions. After other variables were controlled by multiway analysis of variance, the hospital stay of patients who continued the initial medication was 15.2% longer (2.0 days) for divalproex than valproic acid. Switching medications was more common for valproic acid, partly because of study design. Medication intolerance occurred in approximately 6.4% more patients taking valproic acid than divalproex. However, switching from valproic acid to divalproex did not significantly prolong length of stay, over that for continuous divalproex, or increase the rehospitalization rate. CONCLUSIONS: Lower peak valproate concentrations with divalproex sodium may have enhanced tolerability but may also explain the lower effectiveness. Extended-release divalproex could lower effectiveness further and require higher doses. Thus, inpatients are better served by beginning with generic valproic acid and by changing to delayed-release divalproex only if intolerance occurs. This would save up to one-third of inpatient costs and two-thirds of a billion dollars yearly in medication costs.

Valproate is available as a proprietary formulation in enteric-coated delayed-release divalproex sodium tablets (Depakote-DR) and as generic immediate-release valproic acid. The cost differential between the two formulations has steadily risen in the past decade (1). Substituting generic valproic acid for divalproex sodium saves 83% of the cost (1), which would be a $70,000 yearly savings for our hospital and two-thirds of a billion dollars nationwide. Differences in adverse drug reactions have been reported to favor divalproex sodium over valproic acid. With no economically feasible methods for large controlled studies comparing the two, the differences in adverse reactions have been presumed to be clinically significant.

Citing the difference in adverse drug reactions between divalproex sodium and valproic acid, the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee of our hospital left the choice of valproate formulation entirely to the attending physicians. The committee did request prospective information to assess the impact of adverse drug reactions on the length of inpatient stay and the rate of readmissions, suggesting postdischarge noncompliance in the patients treated with valproic acid. We prospectively collected this information from 9,260 admissions of patients who received either divalproex sodium or valproic acid during a 6-year study.

Method

Population and Setting

The system that includes our hospital and the mental health centers is an almost-closed system that provided the study population with inpatient and outpatient services regardless of their financial capabilities. Neither the hospital nor the associated mental health centers restricted or required additional documentation for dispensing divalproex sodium or valproic acid. Moreover, physicians’ prescription patterns were explicitly not individually monitored, further lifting the pressure to prescribe either formulation. Our pharmacy dispensed the name brand if ordered as “Depakote”; otherwise, valproic acid was dispensed. The initial formulation was continued throughout the hospital stay unless altered by the physician.

We included all psychiatric admissions of patients treated with divalproex sodium or valproic acid except those receiving valproic acid concentrate (generally prescribed for noncompliant inpatients with poor prognoses) and 14 participants in a controlled study that dictated the valproate formulation. Also excluded were patients treated with divalproex samples given to the hospital (for reasons unrelated to the study), as the physicians did not freely select the formulation.

Medications and Procedures

Patients received gelatin capsules of generic immediate-release valproic acid or tablets of delayed- or extended-release divalproex sodium. Most of the latter group (99.82%) received the delayed- rather than the extended-release formulation.

Bed demand limited assignment of a readmitted patient to the same physician at subsequent hospitalizations. Admitted patients were assigned to hospital units (wards), and thus to treating physicians, on the basis of arrival time and bed availability only and no other criteria (except age requirements for the child and adolescent unit and older adult unit). This provided what we believe to be the naturalistic equivalent of true prospective random assignment of subjects to different units, and thus to treating physicians, especially because of the large sample size.

Rather than following forced blinded medication assignment in our active treatment facility, physicians were allowed to initiate treatment with either valproic acid or divalproex sodium. They freely switched medications without restrictions, on the basis of what they believed to be in the patients’ best interest. We were, nevertheless, aware of possible indication bias (2) (bias affecting the physicians’ choice of valproate formulation) and bias about the appropriate length of hospital stay.

Two of the authors (D.E.W., A.L.R.) devised an adverse drug reaction monitoring and early warning system to closely monitor, among other variables, adverse reactions to valproate. Certain medication orders (discontinuation, sudden dose reduction, or switch from one to the other formulation) triggered a concomitant inquiry by one of the authors. This included a patient interview, a medical record examination, and a case discussion with the unit nurses, and occasionally with the physician, to determine whether the medication change resulted from adverse drug reactions. The medication order itself was not challenged. Physicians were generally unaware of the exact reason for the pharmacists’ visits, as the pharmacists perform several duties on the units. The design of the study of adverse drug reactions favored divalproex sodium; physicians who believed that divalproex sodium was better tolerated were likely to switch from valproic acid to divalproex sodium, rather than the opposite. Also, adverse drug reactions made the physicians more willing to switch valproate formulations for patients receiving valproic acid, while giving divalproex sodium more time to see whether the adverse drug reactions were transient.

There was no guarantee that the physicians accessed or used the information on prior adverse drug reactions that was available in the old medical records and online discharge summary. Our pharmacy computers did not automatically enter the previously identified adverse drug reactions into the current pharmacy patient record.

Human Subjects Considerations

With no consensus about differential adverse drug reactions or effectiveness, the patients signed the same consent form to receive either valproic acid or divalproex sodium. The patients did not sign research consent forms, as monitoring adverse drug reactions and collecting information to decide medication budget allocations are routine safety functions. In addition, the study did not change care or risk levels. The institutional review board approved publishing the study outcome.

Statistical Analysis

The primary a priori outcome variable was length of hospital stay. The secondary outcome variables were rehospitalization rate and valproate medication switches (i.e., discontinuation, dose reduction, or formulation change) confirmed by the researchers to be secondary to adverse drug reactions.

We used the valproate formulation (divalproex sodium or valproic acid) initially prescribed as the drug treatment classification for the analyses of length of stay, and we used the last formulation given for rehospitalization analyses. Categorization of drug sequence was based on four possible sequences of the two formulations from the initial to the last part of treatment: divalproex to divalproex, valproic acid to valproic acid, divalproex sodium to valproic acid, and valproic acid to divalproex. For example, the last group began treatment with valproic acid and then was switched to divalproex sodium.

General analysis strategy

We first evaluated whether the initial treatment assignment to divalproex sodium versus valproic acid systematically related to the available demographic, clinical, and treatment factors. Separate chi-square analyses and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for these evaluations. Because several of the factors proved to be significantly related to treatment assignment, we pursued additional analyses to determine whether the magnitude or direction of the apparent treatment effects might be attributed to the concomitant factors (3). The analyses of length of stay and readmission were consequently pursued in three ways: 1) unadjusted for concomitant factors (ANOVA), 2) adjusted only for the combination of concomitant variables that independently affected the initial treatment assignment, when the variables were considered in combination (multiway ANOVA), and 3) adjusted for the effects of all the concomitant variables available in the study (multiway ANOVA).

We anticipated that multiple admissions of the same individual were likely in the naturalistic environment of our hospital. As a first step, we used the entire data set (9,260 admissions). This provided an estimate of the effects of the study medications, as actually used in our hospital, for all the admissions, including the most recidivist patients. We next tackled the correlated errors associated with multiple admissions of some patients by excluding all subsequent admissions of the same individuals. This analysis estimated medication group differences in the 5,228 patients based only on their first admission during the study period. For further confirmation, we evaluated differences in length of stay for the 2,690 patients admitted for the first time ever to our hospital. The latter analysis also reflected differential response in the patients with more recent onset of severe mental illness. We first compared the groups classified by the initial medication assignment and then further compared them according to the classification of medication sequence within the admission (divalproex to divalproex, valproic acid to valproic acid, divalproex to valproic acid, and valproic acid to divalproex).

Finally, we compared the mean lengths of stay for the two formulations within a group of 670 patients who were treated with divalproex sodium during one or more hospital stays and with valproic acid during others. Since each patient was represented in both the divalproex and valproic acid conditions, the repeated-measures analyses reduced interpatient variability and also controlled further for differences that result from possible systematic assignment of more treatment-resistant patients to one of the treatment groups.

Data on readmission category (readmitted versus not readmitted) were analyzed by using multiway ANOVA as an alternative to complex multiway contingency table analysis (since the large sample size allowed for reliance on the binomial approximation to the normal distribution). We controlled for the effects of concomitant variables and the confound of multiple admissions of the same patient in these analyses also, as already outlined.

Statistical software and statistical notes

All analyses were conducted by using SPSS for Windows, version 11.0.1 (4). Two-tailed p values of ≤0.05 were considered for statistical significance. To adjust for the effects of concomitant variables in the a priori group comparisons of length of stay and readmission rates, we used a multiway ANOVA main effects model (except where otherwise indicated) and type III sum of squares. ANOVAs of the length of stay were actually performed on log-transformed data, which effectively normalized the positively skewed distribution of the lengths of stay. Only the primary diagnosis designated by the attending physician was considered as the patient’s diagnosis.

Patient age was not used in the analysis, as patients outside the age range of 17–54 years were directly admitted to age-specific hospital units, bypassing the naturalistic randomization. Age had an effect on length of stay. However, differences in length of stay among medication groups did not depend on patient age when entered in the multiway ANOVA for length of stay (either as a continuous covariate or when categorized as below 17, 17–54, or 55 and above). Because age was confounded with hospital unit assignment, we entered only the more comprehensive unit assignment as a control variable in the subsequent multiway ANOVA.

Results

A total of 5,228 separate patients received initial treatment with divalproex sodium or valproic acid during their combined 9,260 admissions and readmissions. During only 9.7% of the 9,260 hospitalizations, or 897, was the initial medication switched to the other formulation for any reason, including adverse drug reactions.

Patient Characteristics

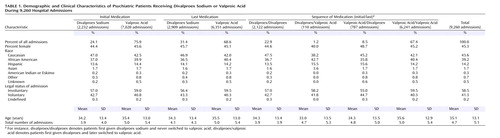

With large samples, statistical significance alone does not necessarily represent clinically meaningful differences between treatment groups. For instance, this was evident in the difference in age between groups (Table 1); the patients initially treated with valproic acid were only 1 year older on average, but the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001, t test). However, the 28.2% higher number of past admissions in patients initially treated with valproic acid (p<0.001, t test) suggests that those patients might have meaningfully poorer outcomes than the patients initially treated with divalproex sodium. Gender and legal status did not differ by initial medication (p=0.32 and 0.11, respectively).

The patients receiving valproic acid at the time of discharge were a year older, were 6.9% less likely to have had voluntary admissions, and had 22.0% more past admissions (p<0.001, p=0.007, and p<0.001). The gender distributions were similar in the groups classified by discharge medication.

There were also differences among the groups classified by valproate formulation sequence. The group receiving valproic acid both initially and last was 1.3 years older, were 4.4% more likely to have had involuntary admissions, and had 1.1 more past psychiatric admissions than the divalproex/divalproex group (p<0.001, p=0.05, p<0.001). Gender did not differ. The divalproex/divalproex group was similar to the valproic acid/divalproex group in age, gender, and admission legal status, but the latter group had an average of 0.9 more past hospitalizations (p<0.001). Finally, the valproic acid/divalproex group differed in mean age from the valproic acid/valproic acid group by 1.3 years (p=0.01). The latter group were 8.2% more likely to have had involuntary admissions (p=0.02), but the gender distributions and numbers of prior admissions were similar. Thus, there was somewhat greater prestudy and past psychiatric psychopathology in the valproic acid groups.

Factors Affecting Medication Assignment

Several concomitant variables were judged to possibly affect treatment outcome by influencing medication assignment in the naturalistic hospital setting. Of particular interest, involuntary legal status suggests poorer prognosis, and the diagnosis of mania is the only psychiatric indication for valproate approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. In addition, the treatment unit (or hospital ward assignment) could affect medication preferences and views about appropriate length of stay for different patients. Also, the admission year could affect the length of stay and views about valproate’s role, since both have changed over time.

We used a chi-square test for nonindependence to assess the effect of each of several concomitant variables, considered separately, on patient assignment to divalproex sodium or valproic acid. The variables included demographic ones, namely gender and race (divided into Caucasian and non-Caucasian), as well as the following clinical variables: total number of admissions to our hospital (below versus at or above the mean of 4.71 [SD=5.11]), admission legal status (voluntary versus involuntary), and diagnosis (bipolar versus not bipolar). Additionally, the two hospital variables, hospital unit and admission year, were also considered. Of these, race, total number of admissions to our hospital, diagnosis, hospital unit, and admission year separately related significantly to treatment assignment.

In view of the large sample size, we then used multiway ANOVA, relying on binomial approximation to normal to identify which of the seven variables independently affected medication assignment, with all the variables considered in combination. Of the seven variables, only diagnosis, hospital unit, and admission year had significant independent effects on medication assignment, all at p<0.001.

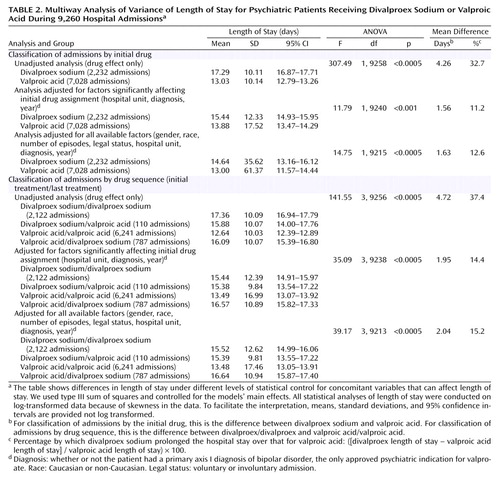

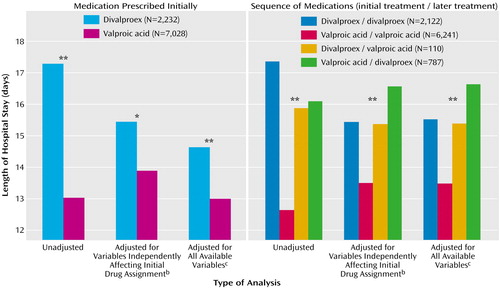

Length of Stay

The median lengths of stay and interquartile ranges for the groups initially treated with divalproex sodium and valproic acid were 15 days (range=10–22) and 11 days (range=7–16), respectively. The values for the medication sequence groups were as follows: divalproex/divalproex, 15 days (range=10–22); valproic acid/valproic acid, 10 days (range=7–16); divalproex/valproic acid, 13 days (range=8–21); and valproic acid/divalproex, 13 days (range=9–20). Table 2 and Figure 1 show the results of the ANOVA and multiway ANOVA for length of stay among all 9,260 admissions. The results are presented by increasing degree of control over the concomitant variables that could potentially affect length of stay. Length of stay was significantly shorter (range=11.2%–32.7%) for valproic acid than for divalproex sodium across different statistical control levels. Outcomes were similar in the drug sequence groups; the length of stay for the patients treated both initially and last with valproic acid was shorter (range=14.4%–37.4%) than that for patients in the divalproex/divalproex group. Tukey honestly significant difference post hoc tests of homogeneous subsets showed that, of the four drug sequence groups, the valproic acid/valproic acid group had the shortest length of stay.

We then used a full factorial ANOVA model, with all possible interactions included in a balanced quasi-experimental design (5), to estimate the effect that treatment would have on length of stay if equal numbers of patients were assigned in a controlled, counterbalanced experiment to all combinations of the different conditions. We included the three variables that independently affected medication assignment (hospital unit, diagnosis, and year of admission) to adjust for their possible effects on length of stay of the medication sequence group. Length of stay differed significantly in the four drug sequence groups, independent of the other concomitant factors (F=5.17, df=3, 8847, p=0.001). Length of stay was 1.7 days (12.8%) longer in the divalproex/divalproex group than in the valproic acid/valproic acid group; the mean for the former group was 14.92 days (SD=17.18), with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 14.19–15.65, whereas the mean for the latter group was 13.23 days (SD=27.65, 95% CI=12.54–13.91).

We repeated the analyses of length of stay using only the first admission of each patient during the study (N=5,228) to eliminate the correlated error that results from multiple admissions of some patients. When none of the variables was controlled for, the length of stay for the valproic acid group (mean=13.11, SD=9.82, 95% CI=12.79–13.43) was shorter than that for the divalproex sodium group (mean=17.62, SD=9.83, 95% CI=17.13–18.10) (F=263.14, df=1, 5226, p<0.001). Additionally, controlling for only the variables that independently affected initial medication assignment showed similar results (mean=13.90, SD=15.19, 95% CI=13.41–14.40, versus mean=15.44, SD=12.75, 95% CI=14.82–16.07) (F=8.86, df=1, 5207, p=0.003), as did controlling for all the variables (mean=14.18, SD=17.39, 95% CI=13.62–14.75, versus mean=15.78, SD=13.73, 95% CI=15.11–16.45) (F=10.00, df=1, 5189, p=0.002).

The results were also similar when the medication sequence groups replaced the groups classified by initial medication. Additionally, length of stay consistently did not differ significantly between the divalproex/divalproex and the valproic acid/divalproex groups. Thus, even failing to tolerate valproic acid did not significantly prolong the length of stay beyond that expected for patients in the divalproex/divalproex group.

Further sample restriction involved only patients hospitalized for the first time at our facility (N=2,690). This changed the direction and magnitude of the results little under all three degrees of statistical control. For example, when we controlled for only the variables that independently affected the initial medication assignment, the initial assignment significantly and independently affected length of stay (F=4.00, df=1, 2668, p=0.05). Differences between the two groups favored valproic acid (N=1,989) over divalproex sodium (N=701) by 1.3 days, or 9.3% (mean=13.42, SD=15.39, 95% CI=12.74–14.09, versus mean=14.67, SD=11.57, 95% CI=13.82–15.53). The medication sequence groups also significantly affected length of stay (F=13.72, df=3, 2666, p<0.001), as length of stay in the divalproex/divalproex group (N=673) was 1.6 days (12.3%) longer than that for the valproic acid/valproic acid group (N=1,758) (mean=14.61, SD=11.60, 95% CI=13.73–15.48, versus mean=13.01, SD=14.80, 95% CI=12.32–13.71).

The mean length of stay of the 670 patients who began treatment with divalproex sodium during one or more hospitalizations and began with valproic acid during others was 17.2 days (SD=10.4) for divalproex and 13.2 days (SD=7.4) for valproic acid (t=8.82, df=669, p<0.001), a 30.3% difference.

Rehospitalization

Patients were classified as either having one or more readmissions during the 6-year study or as having no readmissions (coded 1 or 0, respectively). With no adjustment for concomitant factors, the overall readmission rate was somewhat worse (3.8% higher) for patients discharged while taking divalproex than for patients taking valproic acid at discharge (mean=0.55, SD=0.49, 95% CI=0.54–0.57, versus mean=0.53, SD=0.48, 95% CI=0.51–0.54) (F=6.17, df=1, 9258, p=0.02). Similarly, the drug sequence groups differed significantly in readmission (F=10.18, df=3, 5256, p<0.001). The divalproex/divalproex group had a 9.4% higher readmission rate than the valproic acid/valproic acid group (mean=0.58, SD=0.01, 95% CI=0.56–0.60, versus mean=0.53, SD=0.01, 95% CI=0.51–0.54) (p<0.001). However, the differences between the two groups were not significant after we adjusted for the effects of factors that significantly affected the initial medication assignment (four-way drug-by-unit-by-diagnosis-by-year model). The same was true after we restricted rehospitalization to the 5,228 first admissions during the study and the 2,690 that were first hospitalizations at our facility (data not shown). When we corrected for all the seven study variables using a main effects model, the differences in rehospitalization between the groups receiving valproic acid and divalproex at discharge and the differences between the medication sequence groups were also not significant. Hence, discharge drug and drug sequence did not significantly affect the rehospitalization rate. No rehospitalization group differences were noted either when the data were analyzed by initial medication (valproic acid versus divalproex sodium). Thus, the data suggest no negative impact from low-grade adverse reactions to valproic acid, not intense enough to warrant medication change. Also, no lasting valproate aversion followed adverse reactions to valproic acid. Thus, trying valproic acid carried no increased readmission risk, whether it was or was not tolerated.

Adverse Drug Reactions

There were fewer switches from divalproex to valproic acid for any reason (including, but not exclusive to, adverse drug reactions) than switches from valproic acid to divalproex sodium (Mann-Whitney U test: z=8.72, p<0.001). The difference in the rates of switches specifically related to adverse drug reaction was 6.4% in favor of divalproex (Mann-Whitney U test: z=11.37, p<0.001). No formulation switches resulted from lack of effectiveness. Patients who developed adverse effects while taking divalproex sodium were significantly older (mean=42.1 years, SD=13.1) than patients who had adverse reactions to valproic acid (mean=34.9 years, SD=12.7) (t=2.34, df=518, p=0.02). The mean daily valproate doses were comparable in the two groups at the time of the adverse drug reactions (mean=1039.5 mg/day, SD=572.9, and mean=1008.9 mg/day, SD=445.4) (t=0.29, df=526, p=0.77). Thus, the tolerability differences were not due to dose differences.

It is interesting that 14.7% of the admitted patients who were treated with valproic acid during a following episode had been previously switched from valproic acid to divalproex sodium, because this suggests that some physicians fail to recognize prior intolerance. Hence, the true difference in the rate of intolerance between divalproex and valproic acid is 5.5%.

Discussion

The length of inpatient hospital stay was meaningfully shorter in patients who began treatment with valproic acid than those whose initial treatment was divalproex sodium. The difference remained statistically significant regardless of the subpopulation studied or statistical control exercised. There was no increased readmission risk from trying valproic acid first, even in patients who could not tolerate valproic acid and were consequently switched to divalproex sodium. Failure to tolerate valproic acid did not result in a significantly longer hospital stay than that for patients who received divalproex sodium continuously. Adverse reactions to both divalproex sodium and valproic acid were easily managed and produced no subsequent valproate aversion. Thus, physicians should universally start with generic valproic acid for inpatients requiring valproate. The fivefold added expense of delayed-release divalproex sodium remains justified in the 5.5% of patients who cannot tolerate valproic acid.

Valproic acid and delayed-release divalproex are equally bioavailable and identical following absorption. Thus, valproic acid’s higher peak serum concentration might account for its association with a shorter length of stay. Extended-release divalproex (Depakote-ER) has an even lower peak serum concentration (6, 7). Consequently, we now switch patients who cannot tolerate valproic acid to delayed-release, not the extended-release, divalproex.

A limited number of small studies have compared the effectiveness and adverse effects of divalproex sodium and valproic acid (Table 3). While a subset of patients could not tolerate valproic acid (8–10, 12), switching patients already taking divalproex to valproic acid was easily accomplished (1, 11, 13–15). Inferences from earlier studies comparing divalproex sodium and valproic acid are limited by the lack of information on postdischarge compliance and by the inability of some patients to express adverse drug reactions. A retrospective study of 300 medical records by Zarate et al. (16) noted equal effectiveness. The rate of discontinuation of valproic acid because of adverse reactions was 9% higher than the rate for divalproex, but the occurrence of at least one adverse drug reaction did not differ significantly. Only 6.7% switched from valproic acid and tolerated divalproex, a number supporting our rate (6.4%) and package insert information for brand-name valproic acid (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.), which states that gastrointestinal adverse events are “usually transient and rarely require discontinuation of therapy.” Switching from divalproex to valproic acid should produce even fewer adverse drug reactions. (We studied initial treatment.) Thus, our prestudy concerns about intolerance of valproic acid were unwarranted.

Switching from delayed-release divalproex to valproic acid may produce a 10%–14% reduction in the serum concentration of valproate (1, 17, 18), merely reflecting differences in the timing of the trough concentration. This should be clinically insignificant. Changing from the less bioavailable extended-release divalproex to valproic acid requires a 14%–20% dose reduction (6).

For completeness, we provide here the outcome of a separate, but relevant, retrospective review in which we focused on medication switches due to adverse gastrointestinal reactions to valproate (94% of all valproate switches were due to gastrointestinal effects). Gastrointestinal upset predominated, followed by nausea, vomiting, acid reflux, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps. Patients with adverse gastrointestinal effects in the divalproex group were older than those in the valproic acid group (mean age=40.0 years, SD=18.0, and mean=34.8, SD=12.6). The patients with gastrointestinal drug reactions were less than half a year younger than the entire group with adverse drug reactions, while sedation or confusion occurred in older patients (t=2.57, df=525, p=0.01). Gastrointestinal effects resulted in medication discontinuation, dose alteration, or formulation switch for 6.8% fewer patients in the divalproex group than in the valproic acid group (Mann-Whitney U=7310630.0, z=12.39, p<0.001). The rates of other adverse drug reactions did not differ except for a slightly higher rate of sedation with divalproex sodium. Information on the outcomes of the adverse drug reactions was available for 67.5% of the patients with medication changes secondary to adverse gastrointestinal effects. Switching to divalproex sodium resolved the problem in 97.6% of these patients. The reader is, however, reminded that the study design created a strong bias in favor of the tolerability of divalproex sodium. None of the adverse drug reactions was consequential.

The advantages of our adverse drug reaction monitoring and early warning system and the analysis method described herein include suitability for large-scale studies, simplicity, affordability, prospective nature, and seamless integration with the busy context in which it is applied. However, it detects differences only if relapse produces significant and rapid clinical or behavioral consequences (e.g., hospitalization or emergency room visits), not slow, chronic cumulative damage. For this reason, studying antihypertensives, for example, requires more comprehensive and costly approaches, such as those described elsewhere (19).

Our study’s weaknesses include possible physician bias, change in admission criteria over time, and lack of prospective randomization. However, the statistical analyses that controlled for these factors consistently indicated shorter hospital stays for valproic acid than for divalproex sodium. There were no structured interviews, but such is the case in clinical practice. Some patients may have left our mental health system, but differential impact on the study groups is unlikely. The greater effectiveness of valproic acid may be limited to inpatients, since our study was hospital based. The lower effectiveness of divalproex sodium may have resulted from using inadequate divalproex doses, as the trough serum concentration of delayed-release divalproex occurs after the following dose is due. This could have produced a falsely higher valproate concentration (7, 20). Increasing the dose of divalproex sodium might, thus, match its effectiveness to that of valproic acid. However, this would undoubtedly further increase the cost of divalproex sodium only to match the effectiveness of valproic acid. It would likely increase adverse reactions to divalproex too, as higher doses increase several of the adverse reactions to valproate. For now, several issues counter the unequal-dosing argument. As noted earlier, physicians in our study used divalproex and valproic acid at comparable doses, and divalproex and valproic acid are equally bioavailable. Additionally, trough valproate concentrations have not been tightly linked to response, even when valproate is used for seizures.

On the other hand, several factors strengthen the study conclusions: the prospective nature, large sample size, long-term data, and consistent large and clinically meaningful differences. The study was conducted in a real treatment context. Only a few patients were excluded and none dropped out, and these factors differentiate our study from standard clinical trials. The bias in adverse drug reactions favored divalproex sodium. This strengthens our conclusion that initial treatment with valproic acid should be universal. With no reason to suspect diagnosis-based differences in tolerability, the tolerability of generic valproic acid should extend from psychiatric to epilepsy and migraine patients.

In summary, initial inpatient treatment with generic immediate-release valproic acid is most effective. Delayed-release divalproex remains an option for the 5.5% of patients who cannot tolerate valproic acid, despite its fivefold cost. We are unable to recommend extended-release divalproex as an alternative. Using valproic acid would annually save two-thirds of a billion dollars in medication costs and more in hospital costs. In a broader perspective, this study and others (19, 21) suggest the value of rigorously comparing the effectiveness of new medications to older ones in real-life settings and conducting cost-effectiveness comparisons before approving the extensively marketed, and more expensive, new medications. With some limitations, the methods presented herein can aid such comparisons.

|

|

|

Received May 21, 2003; revision received March 16, 2004; accepted April 23, 2004. From the Harris County Psychiatric Center and the University of Texas Health Sciences Center; McKesson Medication Management, Brooklyn Park, Minn.; and Comprehensive Pharmacy Services, Laurel Ridge Hospital, San Antonio, Tex. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Wassef, Rm. 2C-07, HCPC, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, 2800 South MacGregor Way, Houston, TX 77021; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Robert Guynn, M.D., for his advice.

Figure 1. Mean Length of Stay for Psychiatric Patients Receiving Divalproex Sodium or Valproic Acid During 9,260 Hospital Admissions, With Three Levels of Statistical Controla

aThe estimates of length of stay were obtained from multiway analyses of variance (ANOVAs). The p values are results of comparisons of the indicated groups by means of multiway ANOVAs.

bHospital unit, diagnosis, and year.

cGender, race, number of episodes, legal status, hospital unit, diagnosis, and year.

*p=0.001. **p<0.0005.

1. Sherr JD, Kelly DL: Substitution of immediate-release valproic acid for divalproex sodium for adult psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv 1998; 49:1355–1357Link, Google Scholar

2. Slone D, Shapiro S, Miettinen OS, Finkle WD, Stolley PD: Drug evaluation after marketing. Ann Intern Med 1979; 90:257–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Appleton DR, French JM, Vanderpump MPJ: Ignoring a covariate: an example of Simpson’s paradox. Am Stat 1996; 50:340–341Google Scholar

4. SPSS for Windows 11.0.1. Chicago, SPSS, 2002Google Scholar

5. Campbell DT, Stanley JS: Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research on teaching, in Handbook of Research on Teaching. Edited by Gage NL. Chicago, Rand McNally, 1963, pp 171–246Google Scholar

6. Dutta S, Zhang Y, Selness DS, Lee LL, Williams LA, Sommerville KW: Comparison of the bioavailability of unequal doses of divalproex sodium extended-release formulation relative to the delayed-release formulation in healthy volunteers. Epilepsy Res 2002; 49:1–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Freitag FG, Collins SD, Carlson HA, Goldstein J, Saper J, Silberstein S, Mathew N, Winner PK, Deaton R, Sommerville K (Depakote ER Migraine Study Group): A randomized trial of divalproex sodium extended-release tablets in migraine prophylaxis. Neurology 2002; 58:1652–1659Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sherwood Brown E, Shellhorn E, Suppes T: Gastrointestinal side-effects after switch to generic valproic acid. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998; 31:114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Levine J, Chengappa KN, Parepally H: Side effect profile of enteric-coated divalproex sodium versus valproic acid (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:680–681Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wilder BJ, Karas BJ, Penry JK, Asconape J: Gastrointestinal tolerance of divalproex sodium. Neurology 1983; 33:808–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cranor CW, Sawyer WT, Carson SW, Early JJ: Clinical and economic impact of replacing divalproex sodium with valproic acid. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997; 54:1716–1722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bates ER Sr: Replacement of divalproex sodium with valproic acid not clear-cut (letter). Am J Health Syst Pharm 1998; 55:1073.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wagner PG, Welton SR, Hammond CM: Gastrointestinal adverse effects with divalproex sodium and valproic acid (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:302–303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Vadney V, Ricketts RW, Cole RW: Effects on individuals with mental retardation of changing Depakote to Depakene. Ment Retard 1994; 32:341–346Medline, Google Scholar

15. Brouwer OF, Pieters MS, Edelbroek PM, Bakker AM, van Geel AA, Stijnen T, Jennekens-Schinkel A, Lanser JB, Peters AC: Conventional and controlled release valproate in children with epilepsy: a cross-over study comparing plasma levels and cognitive performances. Epilepsy Res 1992; 13:245–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, Narendran R, Tomassini EC, McDonald J, Sederer M, Madrid AR: The adverse effect profile and efficacy of divalproex sodium compared with valproic acid: a pharmacoepidemiology study. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:232–236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Cloyd JC, Kriel RL, Jones-Saete CM, Ong BY, Jancik JT, Remmel RP: Comparison of sprinkle versus syrup formulations of valproate for bioavailability, tolerance, and preference. J Pediatr 1992; 120:634–638Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Dumoulin L, Landry P: Plasma concentration of valproate following substitution of divalproex sodium by valproic acid (letter). Can J Psychiatry 2000; 45:761Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. The ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group: Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 2002; 288:2981–2997; corrections, 2003; 289:178; 2004; 291:2196Google Scholar

20. Pugh CB, Garnett WR: Current issues in the treatment of epilepsy. Clin Pharm 1991; 10:335–358; correction, 10:501Medline, Google Scholar

21. Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, Liu-Mares W, Collins J, Warren S, Leslie D, Allan E, Campbell EC, Caroff S, Corwin J, Davis L, Douyon R, Dunn L, Evans D, Frecska E, Grabowski J, Graeber D, Herz L, Kwon K, Lawson W, Mena F, Sheikh J, Smelson D, Smith-Gamble V (Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on the Cost-Effectiveness of Olanzapine): Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290:2693–2702Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar