Methadone Versus Buprenorphine With Contingency Management or Performance Feedback for Cocaine and Opioid Dependence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Physicians may prescribe buprenorphine for opioid agonist maintenance treatment outside of narcotic treatment programs, but treatment guidelines for patients with co-occurring cocaine and opioid dependence are not available. This study compares effects of buprenorphine and methadone and evaluates the efficacy of combining contingency management with maintenance treatment for patients with co-occurring cocaine and opioid dependence. METHOD: Subjects with cocaine and opioid dependence (N=162) were provided manual-guided counseling and randomly assigned in a double-blind design to receive daily sublingual buprenorphine (12–16 mg) or methadone (65–85 mg p.o.) and to contingency management or performance feedback. Contingency management subjects received monetary vouchers for opioid- and cocaine-negative urine tests, which were conducted three times a week; voucher value escalated during the first 12 weeks for consecutive drug-free tests and was reduced to a nominal value in weeks 13–24. Performance feedback subjects received slips of paper indicating the urine test results. The primary outcome measures were the maximum number of consecutive weeks abstinent from illicit opioids and cocaine and the proportion of drug-free tests. Analytic models included two-by-two analysis of variance and mixed-model repeated-measures analysis of variance. RESULTS: Methadone-treated subjects remained in treatment significantly longer and achieved significantly longer periods of sustained abstinence and a greater proportion drug-free tests, compared with subjects who received buprenorphine. Subjects receiving contingency management achieved significantly longer periods of abstinence and a greater proportion drug-free tests during the period of escalating voucher value, compared with those who received performance feedback, but there were no significant differences between groups in these variables during the entire 24-week study. CONCLUSIONS: Methadone may be superior to buprenorphine for maintenance treatment of patients with co-occurring cocaine and opioid dependence. Combining methadone or buprenorphine with contingency management may improve treatment outcome.

Federal legislation in 2000 and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in 2002 allowed psychiatrists and other physicians to obtain registrations from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency to prescribe buprenorphine, a schedule III partial opiate agonist, for opioid agonist maintenance treatment in office-based practice. This development may greatly expand access to maintenance treatment for untreated opioid-dependent individuals, estimated in 2001 to number more than 600,000 in the United States (1), and provide opportunities for physicians to treat patients outside the specialized setting of narcotic treatment programs. Despite the efficacy of buprenorphine for treating opiate dependence and the lower risk of overdose and abuse liability with buprenorphine, compared to methadone (2–18), the high prevalence and adverse consequences of concurrent cocaine abuse in this population (19) raise questions about the comparative efficacy of buprenorphine and methadone for patients with co-occurring cocaine and opioid dependence and about whether maintenance treatment can be improved by combining it with behavioral treatments, such as contingency management.

Cocaine abuse was found in 42% of those entering methadone treatment and in 22% at 1-year follow-up in a national multisite evaluation (20). Cocaine abuse during opioid agonist maintenance treatment contributes to persistent illicit opioid use (21); a high risk for HIV infection (22–25); higher levels of family, medical, vocational, and legal problems; and a continued focus on drug-related social interactions and criminal activity (26–29). We have no efficacious medication for primary cocaine dependence (30), and methadone maintenance does not specifically reduce cocaine use (29, 31).

Despite initial findings in animal and human studies that buprenorphine decreases cocaine use and possibly the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine more than does methadone (32–39), several randomized clinical trials found comparable or superior efficacy of methadone maintenance, compared to buprenorphine maintenance, for reducing cocaine and illicit opioid use (40–45). These findings led to the study hypothesis that methadone is superior to buprenorphine for co-occurring cocaine and opioid dependence. In animal models, however, cocaine self-administration is reduced most when buprenorphine is combined with access to an alternative, nondrug reinforcer, such as noncaloric sweetened water (46, 47). This finding suggests the possibility, explored in this study, that medications that reduce the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine, such as possibly buprenorphine, would be preferentially enhanced by combining them with alternative rewards.

Contingency management alone or combined with counseling based on the community reinforcement approach can motivate cocaine abstinence in patients without concurrent opioid dependence (48–52). Contingency management has been found efficacious during opioid agonist maintenance treatment in some but not all studies of patients with concurrent cocaine and opioid dependence (53–60), who often show little internal motivation to reduce cocaine use (61). The community reinforcement approach encourages involvement in rewarding, non-drug-related alternatives to illicit drug use; was used in combination with contingency management in the initial studies; and may contribute to persistence of abstinence after discontinuation of contingency management (48, 49, 62).

Consequently, this study compared methadone and buprenorphine and evaluated whether contingency management improved maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine. The two study hypotheses were that 1) methadone is superior to buprenorphine maintenance treatment for reducing illicit opioid and cocaine use and 2) contingency management compared to performance feedback reduces illicit opioid and cocaine use during opioid agonist maintenance treatment. The study also explored whether contingency management leads to greater reductions in cocaine use during buprenorphine rather than methadone maintenance treatment and whether reductions in illicit drug use persist after the value of the voucher rewards used in contingency management is reduced to a nominal level.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 162 individuals seeking opioid agonist maintenance treatment in New Haven, Conn. All subjects were at least 18 years old, had at least a 1-year history of documented opioid dependence, and met the DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence and cocaine abuse or dependence as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (63) conducted by a bachelor’s-level research assistant and confirmed by a psychiatrist. Individuals were excluded from participation if they met any of the following criteria: 1) current alcohol or sedative dependence; 2) significant medical condition (e.g., liver enzyme elevations greater than three times normal limit); 3) current psychotic or bipolar disorder, major depression, or suicide risk; 4) pregnancy; and 5) inability to read or understand English. Potential subjects who met the initial eligibility screening criteria and expressed interest in the study (N=169) between February, 1995, and July, 1998, were referred to the study through a centralized opiate intake treatment and research screening unit, and 163 of these 169 potential subjects enrolled in the study. Reasons for not enrolling included failure to complete intake (N=1), failure to attend the admission session (N=3), presence of a psychiatric condition (N=1), and expectation of incarceration (N=1). Randomization occurred at the time of enrollment. One of the 163 subjects received only one medication dose and provided no additional data; data for this subject were not included in the analyses. The results of analyses with this subject included do not differ from those with the subject excluded.

All eligible subjects provided written, informed, and voluntary consent before enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine.

Treatments

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups (methadone with contingency management, methadone with performance feedback, buprenorphine with contingency management, or buprenorphine with performance feedback) by using a computerized urn randomization procedure to balance the groups with regard to gender and presence of antisocial personality disorder. Subjects and research personnel were informed about allocation to contingency management or performance feedback at the time of randomization.

Community Reinforcement Approach Counseling

Manual-guided counseling with the community reinforcement approach (64) was provided to all subjects in individual sessions twice weekly during the first 12 weeks of the study and weekly during the last 12 weeks by a total of 11 therapists (nine doctoral-level psychologists, one psychiatrist, and one drug counselor with more than 5 years of experience). Therapists received intensive training in community reinforcement approach counseling and weekly individual supervision by a senior therapist with extensive training and experience in behavioral therapy. The community reinforcement approach utilizes behavioral counseling and cognitive and behavioral skills training to help patients develop long-range goals and encourage them to engage in non-drug-related, rewarding activities (64, 65).

Opioid Agonist Maintenance Medications

Opioid agonist maintenance medications were dispensed to subjects daily under direct observation. A research pharmacist who had no direct contact with any of the subjects prepared all medications in advance. To maintain the double blind, all subjects received identical volumes of an oral liquid medication (methadone or placebo) and identical volumes of a sublingual liquid medication (buprenorphine or placebo). Methadone (35 mg p.o.) or sublingual buprenorphine (4 mg) was started on the first day of treatment; the medication dose was increased rapidly during the first 2 weeks of treatment to a predetermined set daily initial maintenance dose (65 mg/day of methadone or 12 mg/day of buprenorphine). The success of the blinding was evaluated by asking each patient during the maintenance phase which medication the patient thought he/she was taking. These assessments were initiated partway through the study and are available for 42 subjects. Most subjects thought they were receiving buprenorphine, regardless of whether they were receiving methadone (72% [18/25] of the methadone patients reported that they thought they were receiving buprenorphine and one reported not knowing) or buprenorphine (88% [15/17] of the buprenorphine subjects thought they were receiving buprenorphine). The initial maintenance dose of methadone was increased by 10 mg and the initial maintenance dose of buprenorphine was increased by 2 mg after 2 weeks if 50% or more of the urine toxicology tests in the preceding week were positive for opiates. A total of two dose increases was permitted (to a maximum daily methadone dose of 85 mg or buprenorphine dose of 16 mg). Medication doses were tapered after completion of 24 weeks of treatment for patients who were not planning to transfer to methadone maintenance treatment.

Contingency Management

Subjects assigned to contingency management earned monetary vouchers for each urine sample that tested negative for both illicit opioids and cocaine, beginning the first week of treatment. Research assistants collected urine from subjects thrice weekly, tested them immediately using on-site testing, and gave subjects a slip of paper indicating the results of each test (negative or positive for illicit opioids or cocaine) and the value of the voucher earned if the sample was drug-free. During the first 12 weeks of maintenance treatment, the value of the voucher increased from the initial $2.50 value in $1.25 increments for each successive drug-free urine sample. Subjects earned a $10 bonus voucher for providing three consecutive drug-free urine samples. The value of the voucher was reset to $2.50 after a drug-positive urine sample, was subsequently increased in $1.25 increments for successive, consecutive drug-free samples, and could return to the previous level after five consecutive drug-free samples. After the first 12 weeks of treatment, the escalating schedule of voucher reward was discontinued, and subjects earned a voucher with a nominal value of $1.00 for each drug-free urine sample. Money earned for drug-free urine samples could be exchanged at any time for goods or services consistent with treatment goals and generally purchased by a project staff member. The maximum value of the vouchers that a subject could earn in contingency management was $1,033.50.

Performance Feedback

To control for the interaction between research assistants and subjects and the provision of feedback about urine toxicology results in contingency management, subjects assigned to performance feedback received an informational slip of paper of no monetary value indicating the results of each urine test (negative or positive for opiates and for cocaine).

Assessments

At baseline, subjects were assessed with the Addiction Severity Index, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (sections for substance use, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and antisocial personality disorder), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (63, 66–68), and urine toxicology testing. Urine samples were obtained three times weekly during treatment under direct observation. On-site toxicology testing used the EMIT system (Syva Company, Cupertino, Calif.), with cutoffs for positive findings set at 300 ng/ml for morphine and for cocaine metabolite. All assessments were administered by trained and experienced research assistants, who were supervised by a research coordinator with many years of experience in drug abuse treatment clinical trials.

Statistical Analyses

Analysis of variance procedures (for continuous variables) and chi-square tests (for categorical variables) were used to compare the baseline characteristics of patients in the four treatment groups. The differences in retention among the four groups were evaluated by using the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis procedure and the log rank test (69–71). The primary outcome measures, assessed by thrice weekly urine testing, were the maximum number of consecutive weeks of abstinence from illicit opioids and cocaine and the proportion of drug-free urine tests. The statistical significance of differences in the maximum consecutive number of weeks of abstinence was evaluated with a two-by-two analysis of variance procedure to test the main effects of the two factors (medication and contingency management) as well as their interaction. The maximum number of consecutive weeks of abstinence provides the best summary measure of varying, arbitrary periods of abstinence (e.g., never abstinent, 1, 3, 6, or 8 weeks of abstinence). For comparison with other studies, we also calculated the proportion of subjects in each group who never had a drug-free urine test or who achieved varying periods of abstinence, and we evaluated the significance of the differences between methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment and between contingency management and performance feedback by calculating odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The statistical significance of differences in the proportion of drug-free urine toxicology tests was evaluated by using the mixed-models procedure to test for the main effects of the two factors, time effects during treatment, and possible interactions among the two factors and time (72). To develop a continuous measure of the proportion of drug-free tests, urine test results were aggregated into eight successive 3-week periods and entered as a repeated outcome measure. Results were also analyzed separately for the proportion of opiate-negative urine tests and of cocaine-negative tests and for the maximum consecutive number of weeks subjects were abstinent from cocaine only and from illicit opioids only. Results are based on 8,201 urine samples (70% of the 11,664 total possible urine samples that could have been collected had all subjects remained in treatment for the entire study). During the time subjects remained in the protocol, 399 of the 8,600 scheduled urine tests (4.6%) were missed. Analyses were conducted for the entire 24-week study period and, to evaluate the effects of contingency management during the time of escalating voucher value, for weeks 1–12.

Because there were significant baseline differences among the treatment groups in race and in the reported number of days of cocaine use in the 30 days before enrollment, we repeated the analyses with adjustment for the effects of these baseline differences. The results of these analyses were similar to those found without adjustment for either variable. Consequently, the results of the analysis of covariance are not reported. Power calculations conducted before the study indicated that the planned sample size of 168 would provide sufficient statistical power (d=0.80) to detect small to moderate treatment effects on the primary outcome measures with an alpha level of 0.05 (73). All analyses were conducted by using SAS version 8.1 (74) and SPSS version 11 (75) statistical packages, with an alpha level of 0.05 and two-tailed tests of significance.

Results

Sample Characteristics

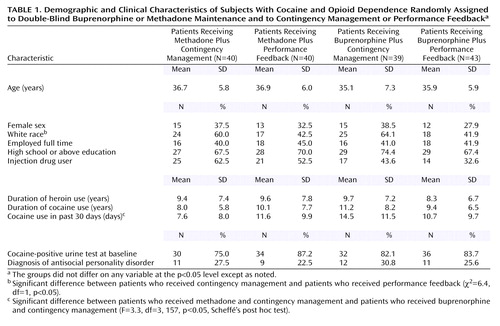

At baseline, there were no significant treatment group differences on most demographic, drug use, and psychiatric history measures (Table 1). Overall, 66% of the subjects were male; 52% were white, 36% black, and 11% Hispanic; 42% were employed full-time at treatment entry; and 70% had completed high school or had a General Equivalency Diploma. The average age was 36.2 years (SD=6.3). Subjects reported an average of 9.2 years (SD=7.2) of illicit opioid use and 9.6 years (SD=7.1) of cocaine use before study entry and an average of 28.7 days (SD=4.6) of heroin use and 11.1 days (SD=10.0) of cocaine use in the past 30 days, 47.5% of the subjects reported current injection drug use at treatment entry, and 27% of the subjects met the criteria for antisocial personality disorder. A significantly greater proportion of subjects assigned to contingency management, compared to those assigned to performance feedback, were white (χ2=6.4, df=1, p<0.05). Subjects in the methadone plus contingency management group reported the fewest days of cocaine use in the 30 days before treatment entry (F=3.3, df=3, 157, p<0.05).

Attrition From Treatment

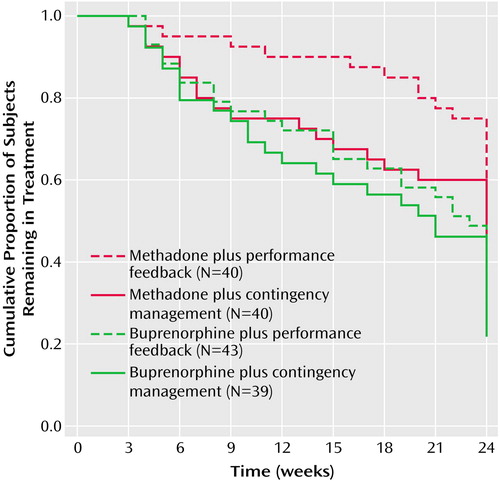

Subjects who received methadone remained in treatment significantly longer than those assigned to receive buprenorphine (log rank=6.4, df=1, p<0.05); there were no significant differences in retention between subjects assigned to contingency management or performance feedback (log rank=1.8, df=1, p=0.18) (Figure 1). Reasons for termination for the 73 subjects who did not complete 24 weeks of treatment included noncompliance (e.g., being verbally abusive or missing 3 consecutive days of medication or 3 consecutive weeks of counseling) (N=53), incarceration (N=13), pregnancy (N=2), psychiatric problems (N=3), elevated liver enzymes values (N=1), or transfer to inpatient drug abuse treatment (N=1). Of the 89 subjects who completed 24 weeks of treatment, 51 transferred to methadone maintenance treatment, treatment with naltrexone, or another treatment, and 38 left without a formal treatment plan during or after detoxification.

Treatment Effects on Illicit Opioid or Cocaine Use

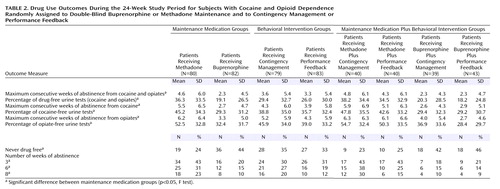

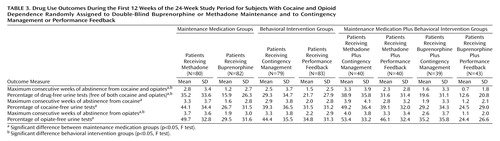

For the 24-week study period, there were significant effects of maintenance medication on the mean maximum number of consecutive weeks abstinent from illicit opioids and cocaine (F=7.4, df=1, 158, p<0.01) (Table 2). Subjects who received methadone achieved significantly longer periods of abstinence than those who received buprenorphine. There were no significant effects of contingency management (F=0.09, df=1, 158, p=0.76) and no significant interaction between medication and contingency management (F=0.10, df=1, 158, p=0.75). For the first 12 weeks (Table 3), however, when vouchers increased in value for successive drug-free urine samples, the effects of both contingency management (F=3.9, df=1, 158, p<0.05) and medication (F=10.7, df=1, 158, p<0.01) were significant; patients who received contingency management plus methadone had significantly longer periods of abstinence. Overall, a significantly higher proportion of methadone compared to buprenorphine subjects achieved at least one drug-free urine sample (odds ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.3–4.9), 3 or more consecutive weeks of abstinence (odds ratio=3.0, 95% CI=1.5–6.2), and 6 or more consecutive weeks of abstinence (odds ratio=2.7, 95% CI=1.2–5.7), but there were no significant differences between the subjects who received contingency management and those who received performance feedback in any of these measures. Of the 26 subjects who were abstinent during weeks 10–12, 12 (71%) of the 17 contingency management subjects who were abstinent, compared to four (44%) of the nine abstinent performance feedback subjects, relapsed during the next 6 weeks, but the differences were not significant (χ2=1.7, df=1, p=0.19).

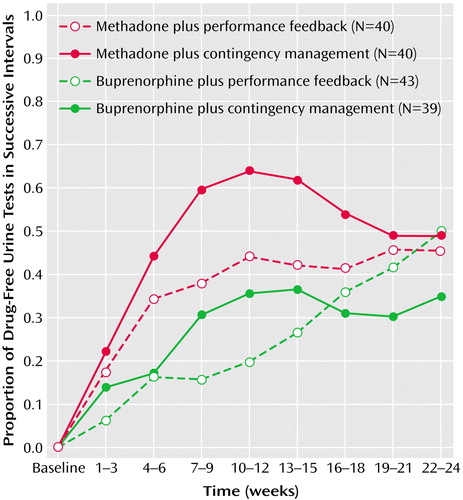

Significant effects on the proportion of drug-free urine tests during the 24 weeks were found for medication, time, and the interaction between medication and time (Figure 2 and Table 2). Cocaine and opiate use decreased significantly over time in all treatment conditions, and subjects who received methadone had significantly greater and faster reductions across the 24 weeks of the study than did the subjects who received buprenorphine. There were no significant differences between the patients who received contingency management and those who received performance feedback in the overall proportion of drug-free urine samples (F=1.3, df=1, 160, p=0.26) and no significant interaction between maintenance medication and contingency management (F=0.7, df=1, 160, p=0.40).

Separate analyses of the proportion of drug-free urine tests for the first 12 weeks of treatment (Table 3) showed similar effects of medication, time, and the interaction between medication and time. During the first 12 weeks, the effect of contingency management was also significant, as was the interaction between contingency management and time. During this period, methadone maintenance was associated with significantly greater and faster increases in the number of drug-free urine tests, compared to buprenorphine maintenance, and contingency management was also associated with significantly greater and faster increases in the number of drug-free urine tests, compared with performance feedback.

The results of separate analyses involving only opioid-negative urine tests and only cocaine-negative urine tests were similar to those found for the primary outcome measure of negative urine tests for both illicit opioids and cocaine (Table 2 and Table 3).

Discussion

The results of this study support the greater efficacy of methadone maintenance, compared to buprenorphine maintenance, and of combining contingency management with methadone or buprenorphine for concurrent cocaine and opioid dependence. Illicit drug use decreased over time both for subjects who received methadone and for those who received buprenorphine, but the subjects who received methadone remained in treatment longer, achieved longer periods of sustained abstinence from illicit opioids and cocaine, provided a greater proportion of cocaine- and opiate-free urine samples, and experienced a faster reduction in illicit opioid and cocaine use. During the period of escalating rewards for consecutive drug-free urine tests, contingency management was associated with longer periods of abstinence and greater and faster increases in the proportion of drug-free urine tests. No significant interaction was found between maintenance medication and contingency management, suggesting that contingency management improves outcome comparably when combined with methadone or buprenorphine.

The study results favoring methadone are consistent with recent double-blind clinical trials (40–44) but not with earlier studies that suggested particular benefits of buprenorphine for concurrent cocaine and opioid dependence (35–39). The doses used in this study for both methadone (range=65–85 mg/day, average maximum dose=80 mg) and buprenorphine (range=12–16 mg/day, average maximum dose=15 mg) are comparable to doses typically used in clinical programs and clinical trials during the period when the study was conducted. The protocol allowed dose adjustments of both medications, so that the differences in efficacy are unlikely to be the result of inadequate dosing with buprenorphine. Dose-dependent reductions in illicit opioid use have been found in systematic studies of methadone doses up to 100 mg/day and of buprenorphine doses up to 16 mg of sublingual liquid daily (5, 41, 76–80); even higher doses of both medications are used in clinical practice and may produce additional benefits in patients with continued illicit opioid use at lower doses. Bioavailability of the sublingual tablet formulations of buprenorphine (buprenorphine only or buprenorphine combined with naloxone in a 4:1 ratio) is approximately 80% of the liquid formulation used in this study (81, 82), and somewhat higher doses may be needed with the tablets.

The benefits of contingency management in this study, evident during the period of escalating reward, were not as pronounced or persistent as has been found in some other studies (53–57, 60) but were greater than those reported in other studies of patients receiving buprenorphine maintenance treatment (58) and of patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment (59). Several factors might account for the differences across studies. Some studies provided rewards contingent on abstinence from cocaine only (53–57), while the current study and some other studies provided rewards contingent on abstinence from both cocaine and illicit opioids (58–60). Abstinence from both cocaine and illicit opioids is an important goal, but setting too high a threshold initially for earning a reward may reduce the effectiveness of contingency management. Rewarding abstinence from cocaine only was associated with reduced illicit opioid use in one (53) but not all (57) studies. Other differences in study methods involve the counseling procedures and the control for contingency management. Providing manual-guided or specified counseling to all participants, as was done in the current and some (58, 59) but not all (53–57, 60) studies, reduces the likelihood that differences in the counseling provided to patients in one group could lead to observed differences in outcome. To control for the effects of performance feedback and the attention of study personnel in interactions between study personnel and subjects at the time of voucher delivery, this study and two prior studies (59, 60) provided urine test results to all participants. Other studies did not provide performance feedback (57) or provided monetary vouchers independent of urine test results (53, 58) to control for the effects of the additional resources provided with contingency management.

Reflecting the severity of drug dependence in this population, a high proportion of subjects in this and other studies (53, 58, 59) never provided a single drug-free urine test and thus never had an opportunity to sample the voucher reward. Allowing patients to sample reinforcers, lowering the threshold for earning a reward (e.g., rewarding reductions in use rather than complete abstinence), or providing very high magnitude monetary vouchers may improve the effectiveness of contingency management (56, 83). Promising alternatives to voucher-based contingency management that may be less costly and more feasible in community treatment settings include the use of an innovative lottery reward system or abstinence-contingent employment or housing (52, 60, 84–88). Strategies to enhance maintenance of abstinence after discontinuation of aggressive contingency management are also needed. Sustaining a longer duration of initial abstinence (e.g., with more prolonged contingency management) or gradual fading of rewards may help with abstinence persistence (51, 89).

One limitation of the present study was that contingency management was initiated at the outset of treatment, while subjects were being inducted into the maintenance medication regimens, a period when it might be most difficult for subjects to abstain from opiates and thus have an opportunity to sample the reward. The study design did not allow for a period of stabilization while taking methadone or buprenorphine, because subjects had to be randomly assigned to treatment group (medication and contingency management or performance feedback) at study entry. Differences in retention might also affect analyses of the proportion of drug-free urine tests, but the pattern of results did not change when other approaches for handling missing data (coding missing data as positive or negative or carrying the last value forward) were used. The findings favoring methadone are likely conservative, because drug use generally worsens after dropout from agonist maintenance treatment. The leveling off in effects of contingency management after 12 weeks was also coincident with a reduction in the frequency of community reinforcement approach counseling (from twice to once weekly). Counseling frequency was reduced after 12 weeks for all subjects, however, and subjects assigned to performance feedback showed continued reductions in illicit drug use during the final 12 weeks. Finally, individuals with current alcohol or sedative dependence or significant medical or other psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings.

In conclusion, illicit opioid and cocaine use is reduced by methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. The greater efficacy of methadone for concurrent opioid and cocaine dependence suggests that patients with continued illicit opioid or cocaine use during buprenorphine maintenance treatment might experience improved treatment response with methadone. Contingency management improved outcomes during both buprenorphine and methadone maintenance, supporting the efficacy of combining opioid agonist maintenance with this behavioral treatment. The leveling off of contingency management effects after the value of the voucher was set to a nominal amount as well as the cost and difficulty of implementing monetary voucher rewards (60, 88) points to the importance of continuing to improve contingency management techniques, evaluating innovative alternatives to voucher rewards, and developing behavioral treatments and counseling approaches that mobilize naturally occurring intrinsic and extrinsic rewards to reinforce abstinence.

|

|

|

Received Nov. 26, 2003; revision received April 13, 2004; accepted May 10, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine; and the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, Mass. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Schottenfeld, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, 34 Park St., Rm. S204, New Haven CT 06519; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01-DA-09413, K24-DA-00445, T01-DA-13108, R01-DA-09803-04A2, and R01-DA-012979.

Figure 1. Proportion of Subjects With Cocaine and Opioid Dependence (N=162) Remaining in Each of Four Treatment Groups Over a 24-Week Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Buprenorphine With Methadone Maintenance and Contingency Management With Performance Feedbacka

aSignificant differences in retention between subjects who received methadone and subjects who received buprenorphine (log rank=6.4, df=1, p<0.05).

Figure 2. Proportion of Drug-Free Urine Tests at Baseline and During Eight Successive 3-Week Intervals for Subjects With Cocaine and Opioid Dependence (N=162) in a Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Buprenorphine With Methadone Maintenance and Contingency Management With Performance Feedbacka

aThe mixed-models procedure was used to calculate the mean proportion of drug-free urine tests for subjects in each of the four treatment groups. For the entire 24-week study period, significant main effects of medication (F=14.9, df=1, 160, p<0.001) and time (F=22.4, df=8, 957, p<0.001) and a significant interaction between medication and time (F=3.2, df=8, 957, p<0.01) were found. During the first 12 weeks, significant main effects of medication (F=20.97, df=1, 160, p<0.001), contingency management (F=4.9, df=1, 160, p<0.05), and time (F=42.9, df=4, 552, p<0.001) and significant interactions between medication and time (F=6.13, df=4, 552, p<0.001) and between contingency management and time (F=2.7, df=4, 552, p<0.05) were found.

1. Rhodes W, Layne M, Bruen AM, Johnston P, Becchetti L: What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs 1988–2000: Report 3264. Washington, DC, Office of National Drug Control Policy, Dec 2001Google Scholar

2. Walsh SL, June HL, Schuh KJ, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML: Effects of buprenorphine and methadone in methadone-maintained subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995; 119:268–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML: Acute administration of buprenorphine in humans: partial agonist and blockade effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 274:361–372Medline, Google Scholar

4. Johnson RE, Eissenberg T, Stitzer ML, Strain EC, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE: Buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: clinical trial of daily versus alternate-day dosing. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 40:27–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE: A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:1290–1297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Johnson RE, Eissenberg T, Stitzer ML, Strain EC, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE: A placebo controlled trial of buprenorphine as a treatment for opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 40:17–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Schottenfeld RS, Pakes J, O’Connor P, Chawarski M, Oliveto A, Kosten TR: Thrice-weekly versus daily buprenorphine maintenance. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:1072–1079Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bickel WK, Amass L, Crean JP, Badger GJ: Buprenorphine dosing every 1, 2, or 3 days in opioid-dependent patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 146:111–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Comer SD, Collins ED: Self-administration of intravenous buprenorphine and the buprenorphine/naloxone combination by recently detoxified heroin abusers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:695–703Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Amass L, Kamien JB, Reiber C, Branstetter SA: Abuse liability of IV buprenorphine-naloxone, buprenorphine and hydromorphone in buprenorphine-naloxone maintained volunteers (abstract). Drug Alcohol Depend 2000; 60(suppl 1):S6-S7Google Scholar

11. Eissenberg T, Greenwald MK, Johnson RE, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML: Buprenorphine’s physical dependence potential: antagonist-precipitated withdrawal in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996; 276:449–459Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fudala PJ, Yu E, Macfadden W, Boardman C, Chiang CN: Effects of buprenorphine and naloxone in morphine-stabilized opioid addicts. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998; 50:1–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Harris DS, Jones RT, Welm S, Upton RA, Lin E, Mendelson J: Buprenorphine and naloxone co-administration in opiate-dependent patients stabilized on sublingual buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000; 61:85–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, Brown J, Batki SL: Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in methadone maintenance patients. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:1095–1101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, Baggott M, Fernandez I, Melby AK, Nath RP: Buprenorphine and naloxone combinations: the effects of three dose ratios in morphine-stabilized, opiate-dependent volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 141:37–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA: Buprenorphine and naloxone alone and in combination in opioid-dependent humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988; 94:484–490Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Weinhold LL, Preston KL, Farre M, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE: Buprenorphine alone and in combination with naloxone in non-dependent humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 1992; 30:263–274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, Williford WO, Chiang CN, Jones K, Collins J, Raisch D, Casadonte P, Goldsmith RJ, Ling W, Malkerneker U, McNicholas L, Renner J, Stine S, Tusel D (Buprenorphine/Naloxone Collaborative Study Group): Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:949–958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Leri F, Bruneau J, Stewart J: Understanding polydrug use: review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction 2003; 98:7–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, Anderson J, Etheridge RM: Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychol Addict Behav 1997; 11:261–278Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Wasserman DA, Weinstein MG, Havassy BE, Hall SM: Factors associated with lapses to heroin use during methadone maintenance. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998; 52:183–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Chaisson RE, Bacchetti P, Osmond D, Brodie B, Sande MA, Moss AR: Cocaine use and HIV infection in intravenous drug users in San Francisco. JAMA 1989; 261:561–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Joe GW, Simpson DD: HIV risks, gender, and cocaine use among opiate users. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 37:23–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bux DA, Lamb RJ, Iguchi MY: Cocaine use and HIV risk behavior in methadone maintenance patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 37:29–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hartel DM, Schoenbaum EE, Selwyn PA, Kline J, Davenny K, Klein RS, Friedland GH: Heroin use during methadone maintenance treatment: the importance of methadone dose and cocaine use. Am J Public Health 1995; 85:83–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kolar AF, Brown BS, Weddington WW, Ball JC: A treatment crisis: cocaine use by clients in methadone maintenance programs. J Subst Abuse Treat 1990; 7:101–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hunt D, Spunt B, Lipton D, Goldsmith D, Strug D: The costly bonus: cocaine related crime among methadone treatment clients. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse 1986; 6:107–122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD: Antecedents and consequences of cocaine abuse among opioid addicts: a 2.5-year follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis 1988; 176:176–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD: A 2.5-year follow-up of cocaine use among treated opioid addicts: have our treatments helped? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:281–284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. de Lima MS, de Oliveira Soares BG, Reisser AA, Farrell M: Pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2002; 97:931–949Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hser YI, Anglin MD, Fletcher B: Comparative treatment effectiveness: effects of program modality and client drug dependence history on drug use reduction. J Subst Abuse Treat 1998; 15:513–523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Foltin RW, Christiansen I, Levin FR, Fischman MW: Effects of single and multiple intravenous cocaine injections in humans maintained on methadone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 275:38–47Medline, Google Scholar

33. Foltin RW, Fischman MW: Effects of methadone or buprenorphine maintenance on the subjective and reinforcing effects of intravenous cocaine in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996; 278:1153–1164Medline, Google Scholar

34. Lukas SE, Mello NK, Drieze JM, Mendelson JH: Buprenorphine-induced alterations of cocaine’s reinforcing effects in rhesus monkey: a dose-response analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 40:87–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Mello NK, Lukas SE, Kamien JB, Mendelson JH, Drieze J, Cone EJ: The effects of chronic buprenorphine treatment on cocaine and food self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1992; 260:1185–1193Medline, Google Scholar

36. Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Bree MP, Lukas SE: Buprenorphine suppresses cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. Science 1989; 245:859–862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kosten TR, Rosen MI, Schottenfeld R, Ziedonis D: Buprenorphine for cocaine and opiate dependence. Psychopharmacol Bull 1992; 28:15–19Medline, Google Scholar

38. Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C: Treatment of cocaine abuse with buprenorphine. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 26:637–639Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C: Role of opioid antagonists in treating intravenous cocaine abuse. Life Sci 1989; 44:887–892Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Ling W, Wesson DR, Charuvastra C, Klett CJ: A controlled trial comparing buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in opioid dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:401–407Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Schottenfeld RS, Pakes JR, Oliveto A, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR: Buprenorphine vs methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:713–720Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M: Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002(4):CD002207Google Scholar

43. Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE: Comparison of buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1025–1030Link, Google Scholar

44. Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE: Buprenorphine versus methadone in the treatment of opioid-dependent cocaine users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994; 116:401–406Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. West SL, O’Neal KK, Graham CW: A meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of buprenorphine and methadone. J Subst Abuse 2000; 12:405–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Comer SD, Lac ST, Wyvell CL, Carroll ME: Combined effects of buprenorphine and a nondrug alternative reinforcer on IV cocaine self-administration in rats maintained under FR schedules. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 125:355–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Rodefer JS, Mattox AJ, Thompson SS, Carroll ME: Effects of buprenorphine and an alternative nondrug reinforcer, alone and in combination on smoked cocaine self-administration in monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997; 45:21–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Fenwick JW: A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1218–1224Link, Google Scholar

49. Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Badger G: Achieving cocaine abstinence with a behavioral approach. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:763–769Link, Google Scholar

50. Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ: Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:568–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Higgins ST, Wong CJ, Badger GJ, Ogden DE, Dantona RL: Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and 1 year of follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:64–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ: Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: how low can we go, and with whom? Addiction 2004; 99:349–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Silverman K, Higgins ST, Brooner RK, Montoya ID, Cone EJ, Schuster CR, Preston KL: Sustained cocaine abstinence in methadone maintenance patients through voucher-based reinforcement therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:409–415Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Silverman K, Wong CJ, Umbricht-Schneiter A, Montoya ID, Schuster CR, Preston KL: Broad beneficial effects of cocaine abstinence reinforcement among methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:811–824Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML: Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 146:128–138Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Preston KL, Umbricht A, Wong CJ, Epstein DH: Shaping cocaine abstinence by successive approximation. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001; 69:643–654Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, Shoptaw S, Farabee D, Reiber C, Ling W: A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:817–824Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Downey KK, Helmus TC, Schuster CR: Treatment of heroin-dependent poly-drug abusers with contingency management and buprenorphine maintenance. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 8:176–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Piotrowski NA, Tusel DJ, Sees KL, Reilly PM, Banys P, Meek P, Hall SM: Contingency contracting with monetary reinforcers for abstinence from multiple drugs in a methadone program. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 7:399–411Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Petry NM, Martin B: Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine- and opioid-abusing methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:398–405Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Margolin A, Avants SK, Rounsaville B, Kosten TR, Schottenfeld RS: Motivational factors in cocaine pharmacotherapy trials with methadone-maintained patients: problems and paradoxes. J Psychoactive Drugs 1997; 29:205–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Budney AJ: Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer term cocaine abstinence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 8:377–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), Clinician Version. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

64. Budney AJ, Higgins ST: A Community Reinforcement Plus Vouchers Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction: NIDA Therapy Manual for Drug Addiction: Manual 2: NIH Publication 98–4309. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1998Google Scholar

65. Schottenfeld RS, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Pakes J: Community reinforcement approach for combined opioid and cocaine dependence: patterns of engagement in alternative activities. J Subst Abuse Treat 2000; 18:255–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Radloff LS, Teri L: Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale with older adults. Clin Gerontol 1986; 5:119–136Crossref, Google Scholar

67. Radloff LS: The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991; 20:149–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat 1992; 9:199–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Selvin S: Statistical Analysis of Epidemiological Data. New York, Oxford University Press, 1991Google Scholar

70. Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, Shea MT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT: Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data: application to the NIMH treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program dataset. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:739–750Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Allison PD: Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

72. Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

73. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

74. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 8.1. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2000Google Scholar

75. SPSS 11.5.5 for Windows Brief Guide. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 2001Google Scholar

76. Strain EC, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA, Stitzer ML: Moderate- vs high-dose methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized trial. JAMA 1999; 281:1000–1005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE: Dose-response effects of methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119:23–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Schottenfeld RS, Pakes J, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR: Buprenorphine: dose-related effects on cocaine and opioid use in cocaine-abusing opioid-dependent humans. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 34:66–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Bickel WK, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA, Jasinski DR, Johnson RE: Buprenorphine: dose-related blockade of opioid challenge effects in opioid dependent humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1988; 247:47–53Medline, Google Scholar

80. Mello NK, Mendelson JH: Buprenorphine suppresses heroin use by heroin addicts. Science 1980; 207:657–659Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Mendelson J, Upton RA, Everhart ET, Jacob P III, Jones RT: Bioavailability of sublingual buprenorphine. J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 37:31–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82. Nath RP, Upton RA, Everhart ET, Cheung P, Shwonek P, Jones RT, Mendelson JE: Buprenorphine pharmacokinetics: relative bioavailability of sublingual tablet and liquid formulations. J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 39:619–623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML: Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcer magnitude. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 9:317–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84. Milby JB, Schumacher JE, Wallace D, Frison S, McNamara C, Usdan S, Michael M: Day treatment with contingency management for cocaine abuse in homeless persons: 12-month follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71:619–621Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Silverman K, Svikis D, Robles E, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE: A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: six-month abstinence outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 9:14–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Silverman K, Svikis D, Wong CJ, Hampton J, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE: A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: three-year abstinence outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 10:228–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Schumacher JE, Usdan S, Milby JB, Wallace D, McNamara C: Abstinent-contingent housing and treatment retention among crack-cocaine-dependent homeless persons. J Subst Abuse Treat 2000; 19:81–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88. McLellan AT: Moving toward a “third generation” of contingency management studies in the drug abuse treatment field: comment on Silverman et al (2001). Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 9:29–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

89. Preston KL, Umbricht A, Epstein DH: Abstinence reinforcement maintenance contingency and one-year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 67:125–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar