Relationship of Parent and Child Informants to Prevalence of Mania Symptoms in Children With a Prepubertal and Early Adolescent Bipolar Disorder Phenotype

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A controversy regarding pediatric bipolar disorder is whether to use child in addition to parent informants. To investigate this issue, the authors conducted a study comparing separate child and parent interview data for child bipolar disorder. METHOD: Responses on the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia from 93 child and 93 parent informants were compared by using kappa statistics. Research nurses, blind to subject information, separately interviewed parents about their children and children about themselves. Different nurses were used for the parent and child in each family to avoid bias from the same research nurse interviewing a child after interviewing that child’s parent. Mania was defined by DSM-IV criteria, with at least one of the two cardinal symptoms of mania (elated mood and/or grandiosity), to avoid diagnosing mania by symptoms that overlapped with those for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). RESULTS: Parent-child concordance was poor to fair for all cardinal and noncardinal mania symptoms. Kappas were not significantly different by age within the 7–14-year-old age range. CONCLUSIONS: Symptoms endorsed by just the child included substantial proportions of bipolar symptoms that have been shown to best differentiate mania from ADHD (i.e., elation, grandiosity, flight of ideas, racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep). These findings support the need for child informants in research on prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder in children ages 7–14. Differences in mania symptom profiles between investigative groups may be, in part, due to whether child informants were assessed.

To our knowledge, no other study has compared parent to child informants in systematically assessed subjects with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Child informants, however, may be especially important for the assessment and diagnosis of prepubertal and early adolescent mania because of differences in symptom profiles reported by major investigative groups (1–3). Specifically, studies that examined child informants found a symptom distribution that resembled that described for severely ill adults with bipolar I disorder (4). In contrast to this picture of adult-type bipolar I disorder, other investigations did not include child interviews and found a profile characterized primarily by irritable mood and conduct-disordered behavior (3). Because some groups describing nonadult-type symptom profiles did not interview children under the age of 12 (3), there was a question of whether differences between studies might be due, in part, to whether child informants were used.

It was hypothesized that child informants would be important in diagnosing prepubertal and early adolescent mania because of reports in the literature of low agreement beyond chance between parent and child ratings (obtained by direct interviews of the informants) for other internalizing disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) (5–12). In child psychiatry, internalizing disorders refer to those primarily characterized by nonobservable symptoms (e.g., racing thoughts) as opposed to externalizing disorders that include observable pathology (e.g., hyperactivity).

In 1995, when the Phenomenology and Course of Pediatric Bipolar Disorder study began, it was the first investigation funded by the National Institute of Mental Health on the phenomenology and longitudinal course of children with prepubertal and early adolescent mania. To establish credibility for the existence of mania in children amid contention in the field (1), our group elected to study a phenotype with conservative diagnostic criteria.

To address ambiguities in the field of pediatric bipolar disorders (1), including how to differentiate prepubertal mania from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), several research strategies were developed (4). First, subjects needed to fit DSM-IV criteria for mania with at least one of the cardinal mania criteria (i.e., elated mood and/or grandiosity). This schema followed the DSM-IV pattern of needing a cardinal symptom of depression (i.e., sad mood or anhedonia) to fit the diagnosis of major depressive disorder. This cardinal symptom approach obviated the problem of diagnosing pediatric bipolar disorder by criteria that overlapped with those for ADHD (e.g., hyperactivity, distractibility) (13, 14). Elated mood and grandiosity were selected because they are highly specific to mania at all ages (2, 15). As etiopathogenetic studies become available (16), both the cardinal symptom definition of DSM-IV major depressive disorder and the cardinal symptom approach to prepubertal and early adolescent mania may need modification.

Another aspect of using the cardinal symptom approach addressed the issue of irritability. Several authors have stressed that child mania is characterized by irritable rather than elated or concurrent elated and irritable moods (3). Indeed, irritability across the age span is a common symptom of mania, as has been reported in numerous studies of bipolar I disorder in adults and in work with bipolar children (2, 15). For example, 87.1% of the subjects with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype had both elated mood and irritability (2). Irritability, however, although very sensitive (i.e., it is present in most cases of mania), is highly nonspecific because it also occurs in multiple other child diagnoses. For example, Aman et al. (17) reported a controlled study of risperidone for irritability and aggression in subjects with a low IQ. Another randomized clinical trial examined risperidone for irritability and aggression in autism (18). More recently, Kim-Cohen et al. (19) investigated whether young adults with multiple psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., eating, substance use, schizophreniform disorders) had a childhood diagnosis. These investigators found that 20%–60% of adults with a psychiatric diagnosis had a childhood disorder characterized by irritability and aggression (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder).

Based on the nonspecificity of irritability, subjects with only irritable mood (i.e., without euphoria) needed to have grandiosity in order to fit the study phenotype. Of note, although subjects only needed to have one of the two cardinal symptoms of mania, 77.4% had both elated mood and grandiosity. Moreover, 87.1% had concurrent irritability and elation (2).

A second strategy was to construct an assessment instrument, the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS), which included mania items specific to the developmental stage of prepubertal children (20, 21). This instrument was necessary because children are developmentally incapable of many manifestations of mania observed in adults with bipolar disorder (e.g., children will not have had four marriages or have “maxed out” their credit cards) (22). The WASH-U-KSADS has demonstrated reliability and 6-month stability and is used in the majority of federally funded grants on pediatric bipolar disorder (1, 21, 23).

By using these research strategies, a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype has been validated by both longitudinal (4, 24, 25) and family (Geller, unpublished data) studies. Subjects with this phenotype were suitable for study of the relationship of child informants to symptom profiles.

Method

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Details of the study inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously reported (2). Briefly, inclusion criteria were boys and girls ages 7–16 years who were in good physical health with a current DSM-IV diagnosis of mania (manic or mixed phase) for at least 2 weeks. A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (26, 27) score ≤60 was needed to establish significant clinical impairment.

Exclusion criteria were having an IQ <70, adopted status, pervasive developmental disorders, schizophrenia, epilepsy or other major medical or neurological disorder, baseline substance dependency or pregnancy, and manic symptoms only while taking medication. There were no family history exclusions.

The rationale for these inclusion and exclusion criteria included the following. Because this was the first federally funded study of the phenomenology of pediatric mania, the subjects were required to be in a current episode of mania and to fit conservative diagnostic criteria. Moreover, a conservative duration for mania was chosen to address controversies in the field (1–4). As noted, one cardinal mania symptom (elated mood and/or grandiosity) was needed to avoid diagnosing mania by symptoms that overlap with those for ADHD. A lower age of 7 was chosen because of the credibility of interview assessments, and an upper age of 16 was selected so that subjects would still be teenagers at the 2-year follow-up point (4). At baseline, the subjects could not have substance dependency or pregnancy to avoid confounding the mental status assessment, but subjects who developed these conditions were retained in the follow-up studies. Adopted subjects were not included because of concurrent family and genetic studies.

Subject Ascertainment

Details of the subject ascertainment methods were previously published (2). In brief, to optimize generalization, subjects were obtained by consecutive new case ascertainment from outpatient child psychiatric and pediatric sites. Inpatient units at these sites were not used because they closed before the start of this study.

Assessment Instruments

The WASH-U-KSADS, a semistructured interview, was separately administered by experienced research nurses to parents about their children and to children about themselves (21). Raters were blind to any information about the subjects. This was accomplished because subjects with mania were interviewed in randomized order with subjects assessed for the two contrast groups (2). Different nurses interviewed the parent and child in each family to avoid any bias from interviewing children after already interviewing their parents. Research nurses had established interrater reliability and were recalibrated annually (21). The WASH-U-KSADS was developed from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—1986 (28) by adding items assessing current and lifetime episodes, onsets and offsets of each symptom and syndrome, expanded items specific to prepubertal mania, a section on rapid cycling, and sections for ADHD and many other DSM-IV diagnoses. Examples of WASH-U-KSADS responses of prepubertal children with mania have been published (22). To establish diagnoses, either parent or child information was used in accordance with the methods of Bird et al. (29). Time frames during child interviews were established by using birthdays, Christmas, Easter, Thanksgiving, other holidays, the beginnings of school terms, and the endings of school terms as reference points.

Mixed mania was defined as overlapping periods of mania and major depressive disorder. Rapid cycling was defined by using modified Kramlinger and Post definitions (30), as detailed by Tillman and Geller (31). Rapid cycling was defined as four cycles per year, ultrarapid cycling was 5–364 cycles per year, and ultradian rapid cycling was ≥365 cycles per year. Notice that unlike the use of cycles in the adult literature in which cycles and episodes are used interchangeably, cycles in this article refer to cycles occurring during episodes (31). For example, an 8-year-old subject was manic for 2 years, during which he had three cycles each day of alternating elation and depression. Seventy-two subjects (77.4%) had ultradian cycling (at least one cycle per day), with a mean number of cycles per day of 3.7 (SD=2.1); thus, they were essentially continuously cycling.

Psychosis referred to pathological delusions and hallucinations.

A Children’s Global Assessment Scale score of ≤60 was needed to ensure impairment at a moderate or severe level (26, 27). The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (26) is a global measure of severity based on psychopathology and on impaired functioning in social, family, school, and work settings. The nurses who administered the WASH-U-KSADS derived the Children’s Global Assessment Scale scores.

Because maternal warmth and living in an intact biological family predicted recovery and relapse at the 2-year follow-up assessment (4), these factors were included in the analysis. Maternal warmth and living situation were assessed with the Psychosocial Schedule for School-Age Children—Revised (32), which was administered separately to parents about their children and to children about themselves. This scale has been shown to have good psychometrics and includes the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index for determining socioeconomic status (32). Impairments reported by either parent or child were used. Thus, if one informant reported high maternal warmth and the other reported low maternal warmth, the overall rating was low maternal warmth.

After complete description of the study to parents and children, informed written consent was obtained from parents, and written assent was obtained from children.

Hypomania

At baseline, there were 10 subjects who had hypomania. Of these, eight developed mania during the 2-year prospective follow-up (4). Thus, there were too few subjects with hypomania for separate analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Reports of mania and major depressive disorder symptoms and diagnoses were analyzed in three groups: those provided only by the parent, only by the child, and by both the parent and child. The kappa statistic was used to measure the extent to which parent-child agreement exceeded chance. Additionally, kappa statistics were calculated by age and gender of the child, by maternal warmth, and by living in an intact biological family. The relationship of the child’s age to parent-child concordance was determined by linear regression analysis. Two-tailed t tests were used to compare kappa statistics by gender, maternal warmth, and living in an intact biological family. SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

There were 93 subjects. The baseline age was 10.9 years (SD=2.6), the age of onset of the current manic episode was 7.3 years (SD=3.5), and the duration of the current episode was 3.6 years (SD=2.6). The proportion of boys was 61%; prepubertal subjects, 57%; and Caucasian subjects, 89%. The mean socioeconomic status was in the second highest of five classes, and the mean Children’s Global Assessment Scale score was 43.3 (SD=7.6). The proportion with comorbid ADHD was 87%; comorbid oppositional defiant or conduct disorders, 76%; and high maternal warmth, 45%; 55% were living in an intact biological family.

Table 1 includes the prevalence of WASH-U-KSADS mania symptoms and diagnoses by those endorsed by just the parent and by just the child. In addition, symptoms and diagnoses reported by both parent and child informants are given. Kappa statistics for comparisons between parent and child informants were in the poor-to-fair range for all mania symptoms.

Kappas for irritability (kappa=0.07) and other noncardinal symptoms of mania (e.g., distractibility [kappa=0.12], accelerated speech [kappa=0.15]) were also poor to fair.

Proportions of total symptoms given just by child informants included 37.0% for racing thoughts, 29.7% for decreased need for sleep, 26.4% for flight of ideas, 19.6% for pathological psychosis, 16.9% for elation, and 13.8% for grandiosity.

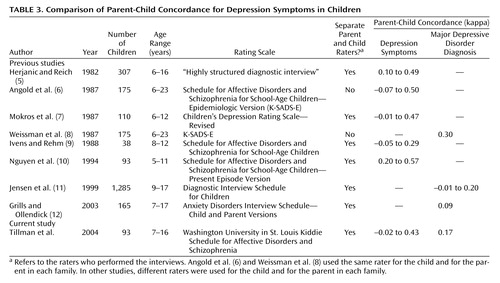

Table 2 shows depressive symptoms by those reported by the parent only, by the child only, and by both parent and child. The total number of subjects in the group with each symptom is also provided. Kappas for the symptoms and diagnosis of major depressive disorder in the 93 subjects were poor to fair, similar to kappas reported by other investigators (5–12), as presented in Table 3.

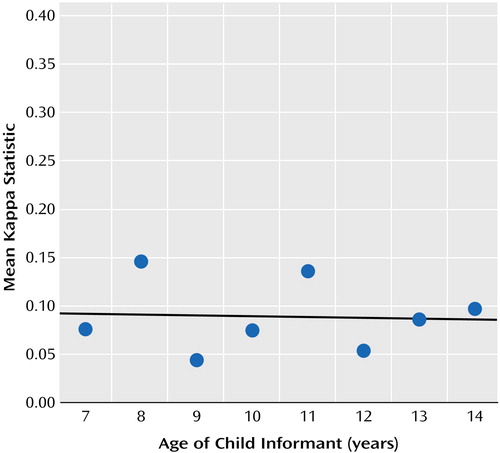

Figure 1 illustrates parent-child concordance on mania items by age of the child informants. Subjects ages 14 to 16 were combined into one group labeled “14” because only two subjects were age 15 and only five were age 16. No significant effect was found for age (F=0.02, df=1, 6, n.s.).

Mean kappas for parent-child concordance on mania items did not differ significantly by gender (male: kappa=0.05 versus female: kappa=0.11; t=0.90, df=15, n.s.), by high versus low maternal warmth (0.06 versus 0.10; t=0.64, df=14, n.s.), or by living in an intact biological family versus living in other situations (0.10 versus 0.04; t=0.89, df=14, n.s.).

Discussion

These findings support the study hypothesis that there would be low parent-child concordance. Because this is the first report to our knowledge of child versus parent informants for prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder, comparisons with other studies of child mania were not possible. Similar studies, as shown in Table 3, however, have been conducted for depressive symptoms (5–12). Kappas for the symptoms and diagnosis of major depressive disorder in the 93 subjects were similar to kappas reported for major depressive disorder by other investigators, which supports the reliability of the method.

These kappas for depressive and anxiety disorders, as Grills and Ollendick (12) have noted, reinforce the need for using child informants to obtain comprehensive assessments of children with internalizing disorders.

As noted, some investigators of prepubertal mania have not interviewed children under the age of 12 (3). In regard to this, data in Figure 1 show no significant differences in parent-child concordance by age of the child informant. These findings strongly support the importance of child informants for the assessment of children with bipolar disorder who are under the age of 12.

Unlike externalizing disorders that have observable behaviors (e.g., ADHD), the thoughts and feelings assessed in internalizing disorders (i.e., mood and anxiety diagnoses) may not be known to parents. Consistent with this internalizing nature of mood disorders, the two highest proportions of mania criteria given only by the child informants were racing thoughts and decreased need for sleep; both are items that parents could well be unaware of.

In a previously reported comparison of symptom profiles between subjects with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype and those with ADHD, five symptoms (elation, grandiosity, flight of ideas/racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep, and hypersexuality) provided the best discrimination of mania from ADHD (2). Some major investigative groups in the field have reported lower rates of these differentiating symptoms (3). One reason for these differences in symptom profiles may be that child informants were not interviewed in some studies (3). There were, however, also a number of other methodological differences between studies that did not use child informants and those that did (2, 3). These differences included not using an instrument that had prepubertal mania-specific items, no use of a severity scale, lay raters rather than experienced clinicians, no cardinal symptom requirement, and ascertainment for ADHD (3). Thus, both assessment of child informants and other methodological differences likely account for the varying prevalence of mania symptoms between investigative groups.

Future studies of parent-child concordance in broadly defined child bipolar disorder phenotypes, primarily characterized by irritability (1, 3), will be informative. In this regard, however, kappas for irritability and other noncardinal symptoms of mania (e.g., distractibility, accelerated speech) were also poor to fair. Therefore, data in this article suggest that poor to fair kappas for parent-child concordance will also be found in other child bipolar disorder phenotypes. These findings support the need to use child informants for comprehensive assessment of prepubertal and early adolescent mania.

|

|

|

Received Jan. 29, 2003; revision received Sept. 24, 2003; accepted Oct. 18, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Geller, School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, 660 South Euclid Ave., MS Box 8134, St. Louis, MO 63110; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-53063 (to Dr. Geller).

Figure 1. Mean Kappa Statistic on Mania Items From the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia by Age of Child Informants in 93 Subjects With Prepubertal and Early Adolescent Maniaa

aNo significant relationship between mean kappa on WASH-U-KSADS mania items and age of child informants (y=0.098–0.0008x) (F=0.02, df=1, 6, n.s.).

1. National Institute of Mental Health Research Roundtable on Prepubertal Bipolar Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:871–878Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, DelBello MP, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Frazier J, Beringer L, Nickelsburg MJ: DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12:11–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chu MP, Wozniak J: Further evidence of a bidirectional overlap between juvenile mania and conduct disorder in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:468–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, Nickelsburg MJ, Williams M, Zimerman B: Two-year prospective follow-up of children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:927–933Link, Google Scholar

5. Herjanic B, Reich W: Development of a structured psychiatric interview for children: agreement between child and parent on individual symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1982; 10:307–324Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Angold A, Weissman MM, John K, Merikangas KR, Prusoff BA, Wickramaratne P, Gammon GD, Warner V: Parent and child reports of depressive symptoms in children at low and high risk of depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1987; 28:901–915Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mokros HB, Poznanski E, Grossman JA, Freeman LN: A comparison of child and parent ratings of depression for normal and clinically referred children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1987; 28:613–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Warner V, John K, Prusoff BA, Merikangas KR, Gammon GD: Assessing psychiatric disorders in children: discrepancies between mothers’ and children’s reports. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:747–753Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ivens C, Rehm LP: Assessment of childhood depression: correspondence between reports by child, mother, and father. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:738–741Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Nguyen N, Whittlesey S, Scimeca K, DiGiacomo D, Bui B, Parsons O, Scarborough A, Paddock D: Parent-child agreement in prepubertal depression: findings with a modified assessment method. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:1275–1283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Jensen PS, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Bird HR, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB: Parent and child contributions to diagnosis of mental disorder: are both informants always necessary? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1569–1579Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Grills AE, Ollendick TH: Multiple informant agreement and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for parents and children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:30–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Fristad MA, Weller EB, Weller RA: The Mania Rating Scale: can it be used in children? a preliminary report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:252–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Craney JL, Geller B: A prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder-I phenotype: review of phenomenology and longitudinal course. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5:243–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR (eds): Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

16. DelBello MP, Axelson D, Geller B: Introduction, in Bipolar Disorder in Childhood and Early Adolescence. Edited by Geller B, DelBello MP. New York, Guilford, 2003, pp 1–5Google Scholar

17. Aman MG, De Smedt G, Derivan A, Lyons B, Findling RL (Risperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group): Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behaviors in children with subaverage intelligence. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1337–1346Link, Google Scholar

18. McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, Cronin P, Hong D, Aman MG, Arnold LE, Lindsay R, Nash P, Hollway J, McDougle CJ, Posey D, Swiezy N, Kohn A, Scahill L, Martin A, Koenig K, Volkmar F, Carroll D, Lancor A, Tierney E, Ghuman J, Gonzalez NM, Grados M, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Davies M, Robinson J, McMahon D (Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network): Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:314–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R: Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:709–717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Geller B, Williams M, Zimerman B, Frazier J: Washington University in St Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS). St Louis, Mo, Washington University, 1996Google Scholar

21. Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo C: Reliability of the Washington University in St Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:450–455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, DelBello MP, Frazier J, Beringer L: Phenomenology of a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder: examples of elated mood, grandiose behaviors, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts and hypersexuality. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12:3–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo CA: Six-month stability and outcome of a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2000; 10:165–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, DelBello MP, Williams M, Zimerman B: One-year recovery and relapse rates of children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:303–305Link, Google Scholar

25. Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K: Four-year prospective outcome of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:459–467Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S: A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1228–1231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Ribera JC: Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:821–824Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Puig-Antich J, Ryan N: The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (KIDDIE-SADS)—1986. Pittsburgh, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 1986Google Scholar

29. Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B: Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:78–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kramlinger KG, Post R: Ultra-rapid and ultradian cycling in bipolar affective illness. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:314–323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Tillman R, Geller B: Definitions of rapid, ultrarapid, and ultradian cycling and of episode duration in pediatric and adult bipolar disorders: a proposal to distinguish episodes from cycles. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13:251–255Google Scholar

32. Lukens E, Puig-Antich J, Behn J, Goetz R, Tabrizi M, Davies M: Reliability of the Psychosocial Schedule for School-Age Children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1983; 22:29–39Crossref, Google Scholar