Who Comes to Voluntary, Community-Based Alcohol Screening? Results of the First Annual National Alcohol Screening Day, 1999

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The feasibility of the 1999 voluntary, community-based National Alcohol Screening Day (NASD) was assessed by determining 1) the extent to which community and college sites were registered to hold screenings and the extent to which the subjects came to participate, 2) the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants at these screening sites, and 3) the extent to which individuals who were referred for evaluation and treatment adhered to follow-up recommendations. METHOD: Registered community and college sites were documented. Screening forms returned by the participants were analyzed. A subgroup of randomly selected participants from community and college sites was contacted by telephone. RESULTS: A total of 1,218 community sites and 499 college sites participated in NASD. At the 1,089 sites that reported results, 32,876 people participated, 18,043 were screened, and 5,959 were referred for treatment. Forty-three percent of those screened at these sites had a score of 8 or more on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), indicating harmful or hazardous drinking. Only 13% of those screened had previous alcohol treatment. In the subgroup that participated in the follow-up survey (N=704), community participants (N=337) had higher mean scores on the AUDIT than the college participants (N=337). Approximately 50% of the community participants and 20% of the college participants adhered to the recommendation to pursue follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: Voluntary, community-based screening for alcohol problems is feasible and offers education, screening, and referral for many individuals with harmful or hazardous drinking behavior.

Alcohol use disorders are common, with a lifetime prevalence of 14% and a 1-year prevalence of 7.4%. In 1992, nearly 14 million Americans met standard diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders (1). In addition to those individuals with an alcohol use disorder, one national survey estimated that another 20% could be classified as risky drinkers. Risky drinkers are defined as those whose daily consumption of alcohol in any single day during the previous year exceeded two drinks for men and one drink for women (2). Yet in 1994, only an estimated 3.4 million Americans received alcohol treatment (3). This disparity led to the creation of a program called National Alcohol Screening Day (NASD).

NASD was created to provide public education, screening, and referral for treatment when indicated (4). The program was based on a previously established model of voluntary, community-based screening for depression (5, 6). The NASD program was designed to identify and help two target populations: 1) persons in the community who have or are at risk for having alcohol problems and 2) students on college campuses who engage in binge drinking, as well as other students who might benefit from greater awareness and knowledge of the adverse consequences of binge drinking.

A follow-up study of NASD (held in 1999) was designed to investigate the following questions: 1) Was the NASD program feasible? Would community and college sites volunteer to hold screenings, and would participants come for screening? 2) What were the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the individuals who came to NASD in 1999? 3) Did the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the community and college participants differ? 4) To what extent did the individuals referred for additional evaluation and treatment adhere to the follow-up recommendations?

Method

Screening Day Procedures

The NASD program has been previously described (4). Health care facilities and colleges nationwide registered to hold screenings. Each site that was registered for participation received a screening kit with a procedure manual describing the program, screening forms with scoring instructions, and educational brochures, videos, posters, and flyers. In March, a toll-free number and a Web site were advertised so that interested individuals could call and locate a nearby site. Institutions paid a nominal registration fee, but all screenings were free for attendees.

The first NASD took place on April 8, 1999, at 1,717 sites across the United States. There were 1,218 community sites and 499 college sites. General and psychiatric hospitals comprised the majority of community sites. The attendees were greeted and given a screening form to complete. The screening form contained questions concerning demographic information and treatment history, as well as the 10-question Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (7), a screening self-test. The AUDIT, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), is used to identify individuals whose alcohol consumption has become hazardous or harmful to their health (8–17). Hazardous drinking is a pattern of drinking involving drinkers who have not yet experienced alcohol-related problems but consume alcohol in a pattern that puts them at high risk for developing such problems. Harmful drinking involves drinkers who have already experienced physical or mental harm due to their drinking but are not yet dependent on alcohol (18).

After the attendees completed the screening form, they were given the opportunity to meet privately with a qualified health professional to review the results of their written screening test and, if necessary, receive referral information. The screening sites were asked to return the screening forms to the NASD organizers.

Follow-Up Procedures

The methods of the follow-up study were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of McLean Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from those who wished to participate in the follow-up study by asking that they provide their first names and telephone numbers after reading and understanding the informed consent statement:

In order to better evaluate the effectiveness of National Alcohol Screening Day, the program will be conducting a follow-up survey of volunteer participants. The survey will be conducted by telephone and will take 10–20 minutes. All data collected will be anonymous and used only for research purposes. The research will be conducted in accordance with all applicable state and federal laws. There is no provision for medical or monetary compensation in the event of physical or psychological injury resulting from this research, however, there are no known risks to participation and the survey is not expected to cause any injury. _____Yes, I would like to participate in a follow-up survey. I understand my participation is completely voluntary. First name: _______________. Telephone number: ______________0.

Those who did not wish to participate left this statement blank. All returned forms that were complete, signed, and included the subject’s telephone number were eligible for inclusion in the follow-up study.

Interviews were conducted with the use of a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system. The interviewing system allowed for administration of the structured questionnaire, as well as the automated collection of data on the calling process (e.g., the number of calls made, the time of each call, and the number of attempts made to complete each call). Eighteen interviewers were trained to administer the interview and to enter the responses for a structured follow-up questionnaire with the use of the computer-assisted telephone interview system. Follow-up interviews were conducted through November 1999. Calls were made during three time periods, between 10:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. E.S.T., 7 days per week, to ensure that all geographic areas and different types of respondents were able to participate.

Scoring the AUDIT

The AUDIT is a 10-question self-test with possible scores ranging from 0 to 40. According to the WHO, a score of 8 or more is consistent with hazardous and harmful drinking; the AUDIT has an overall sensitivity of 92% and an overall specificity of 94% (10). A score of 8 or more indicates a need for further evaluation of an individual’s drinking and possible treatment. Because we did not know the clinical characteristics of the individuals who came to the first NASD and because NASD was designed as a voluntary, community-based screening and not as a primary care treatment, with established clinician-patient relationships, we decided to maximize the sensitivity of the instrument and to instruct clinicians to refer participants for further evaluation and possible treatment if they scored 7 or more on the AUDIT. We also evaluated drinking histories and compliance with referral according to several cutoff scores on the AUDIT, including 7, 8, 11, and 19.

Statistical Methods

Chi-square tests for heterogeneity and trend were used for analysis of categorical variables, and one-way analysis of variance was used to perform unadjusted comparisons of the participants who did and did not comply with the screener’s recommendations. Computations were performed with SAS, version 6.12 (19), and StatXact-4 for Windows (20). The hypothesis tests were two-sided and not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Differences with p values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Attendance at NASD

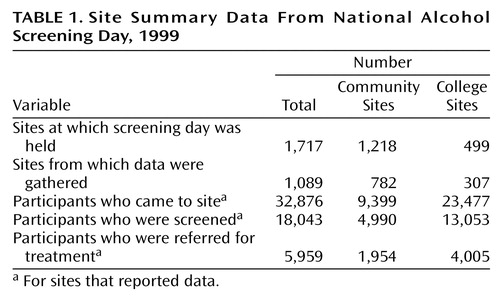

There were 1,218 community sites and 499 college sites; 1,089 (63.4%) of these 1,717 sites reported their results to the NASD organizers. Table 1 summarizes these 1,089 reports of the number of people who attended, were screened, and were referred.

Follow-Up Study Group

A total of 3,959 participants completed screening forms that were eligible for the follow-up study and were returned to administration offices. Of these, 615 forms were removed from the study because the subject’s AUDIT score was 0. In addition, 130 Spanish language forms and 46 forms from respondents under the age of 18 were excluded. Of the remaining 3,168 eligible subjects, 1,500 were “unreachable” by telephone, leaving a total of 1,668. In total, 901 (54.0%) of the 1,668 potential participants were contacted and completed follow-up interviews.

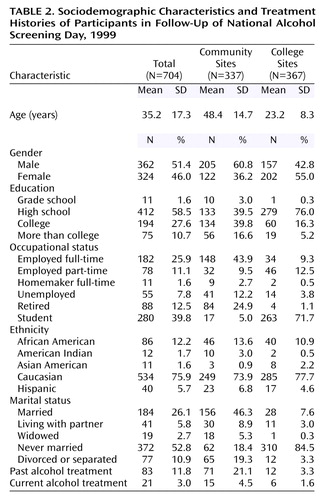

Of these 901 participants, 197 said they took the screening test for a significant other, and 704 came to the screening for themselves. Of these 704 people, 337 were screened at the community sites and 367 at the college sites. Table 2 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and treatment histories of the 704 participants.

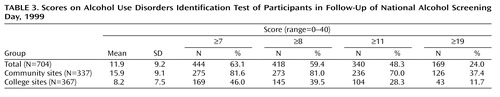

The mean AUDIT scores for the community and college groups and a breakdown of participants by AUDIT cutoff scores are presented in Table 3. We examined several cutoff scores for the AUDIT, including a score of 8, indicating harmful or hazardous drinking according to the WHO (10, 21); 11, indicating harmful or hazardous drinking in a college population (14); and 19, indicating need for immediate treatment (Babor, personal communication, 1998). We also examined a cutoff score of 7 and above, which was the score at which participating clinicians in NASD were instructed to refer participants for further evaluation and treatment.

Table 4 summarizes the self-reported compliance of the participants with the recommendation that they pursue further evaluation and possible treatment. Of the people in the community who were told to see someone for a follow-up visit, 50.7% complied with this recommendation. At the college site, 20.0% of the participants complied with the recommendation to go for a follow-up visit. We asked the participants who were referred for follow-up but did not go to cite the reasons why they did not go. Among these 592 participants, the reasons most frequently cited were as follows: 1) “I was not told to go for follow-up” (49.2%), 2) “I decided I don’t have an alcohol problem” (28.9%), and 3) “I decided I could handle it on my own” (17.9%).

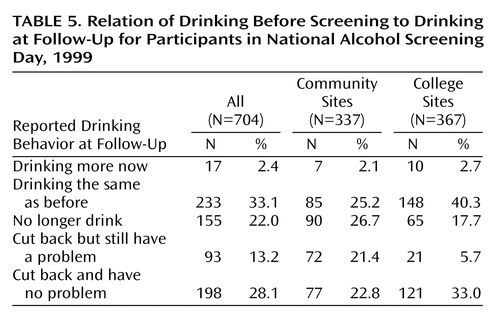

We also compared participants’ self-reported drinking at the time of the screening to their self-reported drinking at the time of the follow-up interview. These results are summarized in Table 5. In the community group, 26.7% reported that they were no longer drinking, and 44.2% said that they had cut back on their drinking. In the college group, 40.3% reported they were drinking about the same at the time of the follow-up as they had been at the time of the screening, 17.7% said that they no longer drink, and 38.7% said that they had cut back on their drinking.

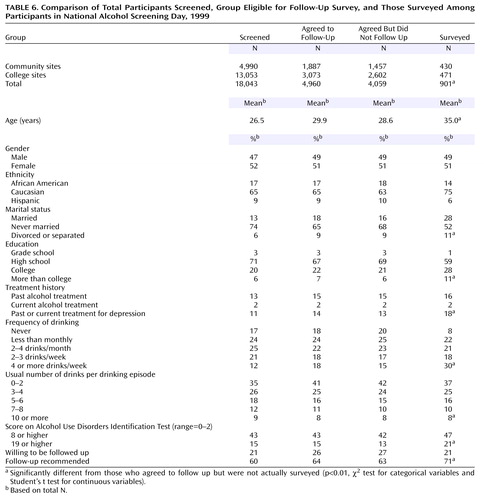

Because the follow-up group was small compared to the total number of individuals reported as having attended and been screened in the first NASD, we compared this subgroup with the entire screened group. Therefore, we compared the characteristics and drinking practices of the persons who were screened (N=18,043) and the subgroup that completed the follow-up survey (N=901) (Table 6). Although statistical comparisons of these groups were not made because of the size discrepancies between groups, it is notable that the AUDIT scores were virtually identical in the total screened group and the subgroup that agreed to the follow-up study. This subgroup was also similar to the entire screened group on measures of frequency and quantity of drinking.

We also compared the persons who actually completed the follow-up survey (N=901) with those who agreed to the follow-up survey but were not surveyed (N=4,059). Those surveyed tended to be slightly older (mean age=35.0 versus 28.6 years), employed full-time (25% versus 20%), married (28% versus 16%), and less likely to be students (33% versus 48%). There were ethnic differences between those surveyed and those who agreed to be followed up but were not surveyed. For example, a larger proportion of those surveyed were Caucasian (75% versus 63%), and a smaller proportion were African American (14% versus 18%) or Hispanic (6% versus 10%) compared with those who agreed to be followed but were not surveyed.

Compared with those who agreed to be surveyed but were not, a greater proportion of those surveyed drank more than 4 drinks per day, (18.0%, 731 of 4,059 versus 14.0%, 126 of 901), scored more than 8 on the AUDIT (46.9%, N=423, versus 42.0%, N=1,705), and scored 19 or higher on the AUDIT (21.0%, N=189, versus 13.0%, N=528). Consistent with these greater AUDIT scores, those who were surveyed were more likely to have been advised to pursue further evaluation and possible treatment (71.0%, N=640, versus 63.0%, N=2,557) than those who had agreed to participate but were not surveyed. These comparisons were all statistically significant at p<0.05.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the NASD program was feasible with 1,218 community sites and 499 college sites participating in this first-time national program of voluntary, community-based alcohol screening. In addition, data collected from the 1,089 sites that reported their results to NASD organizers revealed that almost 33,000 individuals attended the screenings and 18,043 people were screened. Participation in the first annual NASD compared favorably with participation in the 1992 National Depression Screening Day, the second annual event but the first for which results were reported (22). In 1992, 435 facilities registered to participate in National Depression Screening Day, and 5,367 questionnaires of adults screened for depression were returned for analysis (22). In this study group, 53.3% of the respondents had scores that indicated depression (22). Among those who were screened at NASD, fully 43% had AUDIT scores consistent with hazardous drinking. Fifteen percent scored 19 or above, indicating a level of drinking for which immediate intervention is indicated. In spite of the overall high AUDIT scores in the total screened group, only 13% said they had ever been treated for alcohol problems, and 2% reported current treatment for alcohol problems. Sixty-five percent of those screened said they drank three drinks or more on any drinking occasion, and 21% said that they drank seven or more drinks on any drinking occasion. These results indicate that the majority of those who were screened in the 1999 NASD reported drinking levels on any given drinking occasion that are considered above safe limits and consistent with binge drinking. Almost half of the group reported drinking that was consistent with the WHO definition of hazardous drinking (18).

Among the 704 individuals who comprised the follow-up subgroup, almost 60% scored 8 or above on the AUDIT, indicating hazardous drinking and 24% scored 19 or above, a level of drinking for which immediate intervention is indicated. Of importance, mean AUDIT scores differed between community and college groups in the follow-up study. In the community group, 81.0% scored 8 or above on the AUDIT compared with 39.5% of the college group. The differences in the AUDIT scores between these two groups were consistent with other differences in their demographic characteristics. Generally, the community group was older, more likely to have had past alcohol treatment, and had AUDIT scores consistent with hazardous drinking and likely to be consistent with alcohol dependence. The college group was younger, composed predominantly of students, and had lower overall AUDIT scores. On the other hand, although the mean AUDIT scores were lower for the college group, fully 39.5% had AUDIT scores consistent with hazardous drinking. These scores are consistent with other studies that indicate that in the United States, the developmental period of heaviest alcohol consumption for most drinkers is between the ages of 18 and 21 (23). Binge drinking is the type of risky drinking most often engaged in by people of this age group. Binge drinking has been defined as the consumption of four or more drinks at one sitting for women and five or more at one sitting for men (24) and is more prevalent among 18–21-year-old college students than nonstudents (25).

In the community follow-up subgroup, 66.9% said they went for a follow-up evaluation. This included 50.7% of those in the community who said they were told to go for further evaluation. In addition, 26.7% said they were no longer drinking at the time of the follow-up study, and 22.8% said they had cut back and did not think that their drinking was a problem anymore.

In the college group that was surveyed, only 9.5% reported being told to go for further evaluation. However, 17.7% said they were no longer drinking at the time of the follow-up study, and 33.0% said they had cut back and felt that their drinking was no longer a problem.

The present study has a number of limitations. We did not use a probability or a random sample of the survey group. Therefore, it is possible that the follow-up study’s subgroup was not representative of those screened. However, the demographic profile of the follow-up subgroup was similar to the survey group as a whole. The largest differences between these two groups were in part-time employment and marital status. It is unclear regarding the degree to which these characteristics affected the central results of the follow-up study. On the other hand, the AUDIT scores in the total screened group and the subgroup that agreed to be followed up were virtually identical.

Overall, the results of this study demonstrated that NASD is a feasible program by which health care facilities and colleges can volunteer to sponsor screening programs on a designated day and to which members of the general community as well as members of the college community can attend. There were fewer attendees in the general community, but those who attended and were screened were older on average and were more likely to have had alcohol treatment in the past, to have AUDIT scores that were consistent with hazardous drinking, and to be more likely to comply with the recommendation to follow-up and go for further evaluation than were the college participants. The college participants were likely to be younger and to have lower AUDIT scores than the general community participants. These differences were likely to indicate fundamental differences between the two groups that the first NASD served. The community-based screening sites seem to provide screening and referral for individuals with more severe alcohol problems who were more likely to follow through on the recommendation to get additional help. The college screening sites were more likely to serve late-adolescent and young adult students with less severe alcohol problems. These students were not likely to go for further treatment, but a significant minority said they had cut back on their drinking or stopped altogether after the screening.

Voluntary, community-based screening for alcohol problems is feasible and offers education, screening, and referral for many individuals, including those with hazardous alcohol use who have been predominantly untreated in the past. Future screening programs are likely to focus on public awareness of alcohol and health issues, including low-risk drinking and health consequences, as well as to enhance preventive efforts at college sites to help students cut back their alcohol consumption. In addition, increasing the number of participating sites as well as the number of attendees is another important goal. Investigations of future screening programs will employ methods to improve the proportion of those screened who agree to participate in any follow-up survey designed to measure the program’s effect.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received July 31, 2002; revision received Jan. 13, 2003; accepted Jan. 22, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; McLean Hospital; Screening for Mental Health, Wellesley, Mass.; and KAI, Rockville, Md. Address reprint requests to Dr. Greenfield, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill St., Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, grant DA-00407 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (to Dr. Greenfield), and the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust (to Dr. Greenfield).

1. Grant B, Harford T, Dawson D, Chou P, Dufour M, Pickering R: Prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1992. Alcohol Health Res World 1994; 18:243–248Google Scholar

2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Ninth Special Report to the US Congress on Alcohol and Health. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 1997Google Scholar

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies: National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings, 1994. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996Google Scholar

4. Greenfield SF, Keliher A, Jacobs D, Gordis E: The Development of National Alcohol Screening Day. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1999; 6:327–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Greenfield SF, Reizes JM, Magruder KM, Muenz LR, Kopans B, Jacobs DG: Effectiveness of community-based screening for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1391–1397Link, Google Scholar

6. Greenfield SF, Reizes JM, Muenz LR, Kopans B, Kozloff RC, Jacobs DG: Treatment for depression following the 1996 National Depression Screening Day. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1867–1869Link, Google Scholar

7. Babor T, de la Fuente J, Saunders J, Grant M: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1989Google Scholar

8. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Amundsen A, Grant M: Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons With Harmful Alcohol Consumption—I. Addiction 1993; 88:349–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T: A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1997; 21:613–619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M: Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons With Harmful Alcohol Consumption—II. Addiction 1993; 88:791–804Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Barry KL, Fleming MF: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and the SMAST-13: predictive validity in a rural primary care sample. Alcohol Alcohol 1993; 28:33–42Medline, Google Scholar

12. Volk RJ, Steinbauer JR, Cantor SB, Holzer CE III: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screen for at-risk drinking in primary care patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Addiction 1997; 92:197–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD: The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1998; 22:1842–1849Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R: The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict 1991; 26:1173–1185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Foster AI, Blondell RD, Looney SW: The practicality of using the SMAST and AUDIT to screen for alcoholism among adolescents in an urban private family practice. J Ky Med Assoc 1997; 95:105–107Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rubio Valladolid G, Bermejo Vicedo J, Caballero Sanchez-Serrano MC, Santo-Domingo Carrasco J: [Validation of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in primary care]. Rev Clin Esp 1998; 198:11–14 (Spanish)Medline, Google Scholar

17. Daeppen JB, Yersin B, Landry U, Pecoud A, Decrey H: Reliability and validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) imbedded within a general health risk screening questionnaire: results of a survey in 332 primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000; 24:659–665Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol 1995; 56:423–432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. SAS Version 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1997Google Scholar

20. Cytel Software Manual for StatXact-4 for Windows. Cambridge, Mass, Cytel Software Corp, 1998Google Scholar

21. Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB: The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction 1995; 90:1349–1356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Magruder KM, Norquist GS, Feil MB, Kopans B, Jacobs D: Who comes to a voluntary depression screening program? Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1615–1622Link, Google Scholar

23. Chen K, Kandel D: The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am J Public Health 1995; 85:41–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S: Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: a national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA 1994; 272:1672–1677Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J: National Survey Results on Drug Use From the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975–1998, Vol 2: College Students and Young Adults. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1999Google Scholar