Treatment for Depression Following the 1996 National Depression Screening Day

Abstract

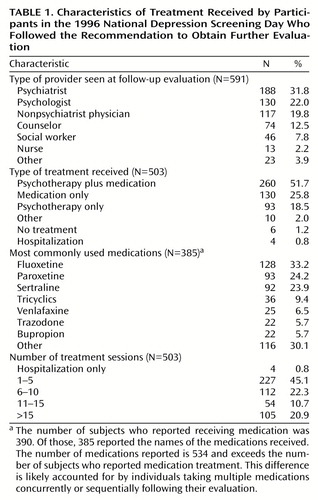

OBJECTIVE: Characteristics of the subsequent treatment received by people who screened positive for depression in the 1996 National Depression Screening Day were investigated. METHOD: A follow-up telephone survey was completed by 1,502 randomly selected participants from 2,800 sites. RESULTS: Of 927 people for whom additional evaluation was recommended, 602 (64.9%) obtained evaluations and 503 (83.6%) received treatment. Of these 503, 260 (51.7%) received psychotherapy and medication, 130 (25.8%) received medication only, and 93 (18.5%) received psychotherapy only. Compared with people without health or mental health insurance, individuals with health insurance (66.7% versus 57.5%) and mental health insurance (74.6% versus 55.3%) were more likely to comply with the recommendation to obtain follow-up evaluation. CONCLUSIONS: One-half of the people treated for depression received a combination of psychotherapy and medication. Lack of insurance was associated with not following the recommendation to obtain further evaluation and treatment.

We previously demonstrated that National Depression Screening Day, a voluntary, anonymous, community-based screening for depression, is feasible (1) and provides an effective way to bring untreated individuals with depression into treatment (2). In order to investigate the type of treatment received by participants who are referred, we conducted a telephone follow-up survey of the 1996 National Depression Screening Day participants. The purpose was to answer the following questions: 1) How many of those who screened positive for depression received treatment? 2) What type of treatment did they receive? 3) What type of treatment providers did they see? and 4) Were there any clinical, sociodemographic, or insurance characteristics that predicted the type of treatment received?

Method

On screening day, the attendees received educational information, filled out self-report anonymous questionnaires that included the 20-item Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (3), had the opportunity to review the screening results with a clinician, and received a referral if appropriate.

The study methods were approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from the people who wished to participate in the study. Informed consent was obtained by asking the participants to read the following informed consent statement, to indicate whether they understood it, and if so, to sign it: “In order to better evaluate the effectiveness of National Depression Screening Day, the program will be conducting a follow-up telephone survey of volunteer participants, 30–60 days after National Depression Screening Day. We would greatly appreciate your participation as it would assist us in improving the program. _____ Yes, I would like to participate in a follow-up survey. I understand my participation is voluntary.” Participants who answered yes were asked to write in their names and telephone numbers. Those who did not wish to participate left this statement blank. Complete forms that included the subject’s telephone number and signed informed consent statement were eligible for inclusion. Between April and May 1997, 13 trained interviewers used a structured questionnaire to conduct interviews. The responses were entered directly into a computer-assisted telephone interview system.

Chi-square tests of heterogeneity and trend were used for categorical variables, and one-way analysis of variance was used to perform unadjusted comparisons of the participants who did and did not comply with the screener’s recommendations. Computations were performed in SAS, version 6.12, and StatXact-4 for Windows. The hypothesis tests were two-sided and not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Differences with p values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

In 1996 there were 2,800 sites in 50 states and Canada, attended by 85,000 people, of whom 62,000 were screened. By randomized stratified sampling, 5,958 completed screening forms with signed consent statements were selected. Of these people, 499 (8.4%) refused to be included in the study, 3,957 (66.4%) were unreachable, and 1,502 (25.2%) completed the follow-up interview.

The majority of the participants were female (67.6%), unmarried (54.3%), employed (62.5%), and Caucasian (86.2%). The mean age was 47.1 years (SD=15.9), with a range of 16 to 87 years, and 96.1% of the participants had never previously attended a depression screening.

There were no significant differences in the Zung depression scale index scores of the interview completers and noncompleters. A somewhat greater proportion of interview completers were female (Pearson χ2=6.30, df=1, p=0.02), married (Pearson χ2=10.12, df=1, p=0.001), and Caucasian (Pearson χ2=23.92, df=1, p=0.001).

Of the 1,502 participants, 78.8% had Zung depression scale index scores consistent with depression, and of these, 80.0% had never previously received treatment. Of the 927 subjects who were referred, 602 (64.9%) obtained further evaluation. Of these 602, 503 (83.6%) received treatment, and 376 (74.8%) were still in treatment after 6 months. Treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Of the treated individuals, 51.7% received a combination of psychotherapy and medication. The type of treatment received differed by sex (Pearson χ2=8.03, df=3, p=0.05). More men than women received psychotherapy plus medication (57.9% versus 49.2%), more women than men received psychotherapy only (20.7% versus 13.1%), and more women than men received medication only (27.1% versus 22.8%). No other sociodemographic or clinical characteristics were associated with the type of treatment received.

Only the index score on the Zung depression scale was associated with the number of treatment sessions. The participants with more severe depression, as indicated by higher Zung depression scale index scores, received more treatment sessions (z score=2.14, two-sided p=0.04).

Individuals with more severe depression were more likely to comply with the recommendation to seek further evaluation (Mantel-Haenszel test for linear association: chi-square=4.83, df=1, p=0.03), as were those with a history of past treatment of depression (Pearson χ2=15.59, df=1, p<0.001). Those with more education were also more likely to follow the recommendation for further evaluation (Mantel-Haenszel test for linear association: chi-square=7.57, df=1, p=0.006). In addition, individuals with health insurance (66.7% versus 57.5%, Pearson χ2=4.17, df=1, p=0.04) and those with mental health insurance (74.6% versus 55.3%, Pearson χ2=34.01, df=1, p<0.001) were more likely to comply with the recommendation to obtain follow-up than those without insurance.

Discussion

This study replicates and strengthens our previous results (1, 2). It is important to note that only 3.9% of the participants had ever previously attended National Depression Screening Day, indicating that each year the screening program serves a mostly untreated, depressed population new to the program.

The proportion of depressed individuals who saw psychiatrists for further evaluation is greater than has been reported in other studies of payment type and clinical specialties (4). This difference may, in part, reflect the proportion of psychiatric treatment facilities that served as screening sites or may indicate preferences in a treatment-seeking population motivated to attend community screenings.

One-half of our sample received combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, and one-fifth received psychotherapy alone. The substantial majority of individuals receiving psychotherapy with or without pharmacotherapy is consistent with others’ findings that mental health specialists are more likely to provide psychotherapy than are general medical providers (4). The greater use of psychotherapy alone for women than for men may indicate sex differences in patients’ treatment preferences or acceptance, or it may indicate sex bias in provider selection of treatments. Finally, having general health and mental health insurance was clearly associated with whether or not depressed individuals in this population sought treatment.

In summary, the majority of participants whose screening results were consistent with depression followed through on the recommendation to obtain further evaluation and receive treatment. A combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was more common than either treatment alone, although women were slightly less likely to receive this combination than were men. Finally, lack of insurance remains a significant barrier to treatment for depressed individuals.

|

Presented in part at the 151st annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 4–9, 1998. Received Aug. 9, 1999; revisions received Jan. 7 and April 11, 2000; accepted May 12, 2000. From the Consolidated Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; the Department of Psychiatry, McLean Hospital; the National Mental Illness Screening Project, Wellesley, Mass.; and KAI Associates, Rockville, Md.; Dr. Muenz is a biostatistical consultant in Gaithersburg, Md. Address reprint requests to Dr. Greenfield, Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Program, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill St., Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants DA-00407 and DA-07252 (Dr. Greenfield); by the Lilly Center for Women’s Health Fellowship, Harvard Medical School; by the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust (Dr. Greenfield); and by the National Mental Illness Screening Project. The authors thank Dawn Sugarman for help in preparing this manuscript.

1. Magruder KM, Norquist GS, Feil MB, Kopans B, Jacobs D: Who comes to a voluntary depression screening program? Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1615–1622Google Scholar

2. Greenfield SF, Reizes JM, Magruder KM, Muenz LR, Kopans B, Jacobs DG: Effectiveness of community-based screening for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1391–1397Google Scholar

3. Zung WWK: A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1965; 12:63–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS: Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar