Views of Potential Subjects Toward Proposed Regulations for Clinical Research With Adults Unable to Consent

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to assess healthy individuals’ attitudes toward five of the most prominent proposed safeguards regarding the consent process for research with adults unable to consent. METHOD: Telephone interviews were conducted with 246 individuals with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease who had participated in clinical research. RESULTS: The majority of respondents said that they were willing to participate in research if they lost the ability to consent. Few completed a research advance directive. Many had discussed their preferences with their families, and the majority would allow their families to make research decisions for them. CONCLUSIONS: Enrolling individuals who are unable to consent in research that offers no potential for medical benefit is consistent with the preferences of at least some individuals. This suggests that such research should not be prohibited, provided there is sufficient evidence that it is consistent with the preferences of individual subjects. Requiring that such evidence be provided in a formal research advance directive may be unnecessarily restrictive. More research is needed to assess whether the findings in this group of subjects generalize to other groups.

By relying on adults’ informed consent, the U.S. regulations for clinical research (45CFR46, “Common Rule”) leave adults who are unable to consent without specific safeguards (1–4). This regulatory gap has taken on critical importance because investigators now realize that research with this population is crucial to making progress on a number of conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia (5, 6).

Several commentators (7–14) and groups (15–18) have proposed safeguards to fill this regulatory gap. The National Bioethics Advisory Commission (15) would exclude adults who cannot consent from riskier research that does not offer a potential for medical benefit, unless it concerns their impairment and they executed an advance directive authorizing their enrollment. Proposals from commissions in Maryland (17) and New York (16) would allow only formally appointed proxies to enroll impaired individuals in riskier research that does not offer a potential for medical benefit.

Because there are no data on individuals’ attitudes, these proposals are based in part on assumptions concerning what individuals think about participating in research if they became impaired. For instance, proposals to allow impaired adults to be enrolled only in research on conditions from which they suffer are based largely on the assumption that individuals are less willing to participate in research on conditions from which they do not suffer. Similarly, proposals for research proxies rely on assumptions concerning individuals’ willingness to allow others to make research decisions for them. Proposals that would bar impaired adults from research that offers no potential for medical benefit assume that individuals are unwilling to participate in such research.

To assess these assumptions, we interviewed 246 individuals with regard to five of the most prominent proposed safeguards regarding the consent process for research with adults who are unable to consent: 1) restrictions on research with no potential for medical benefit, 2) formal research advance directives, 3) proxy decision makers, 4) restrictions on research not associated with the individuals’ impairments, and 5) respect for subjects’ dissent. Finally, the majority of Americans support clinical advance directives, but only about 20% complete one (19–21). Recognizing this gap between preference and performance with respect to clinical advance directives, we also assessed the completion rate for research advance directives. Taken together, these data provide important information for assessing which of the proposed safeguards offer appropriate protection.

Method

Study Group

To ensure the respondents were familiar with clinical research and decision making for those with cognitive impairment, we targeted individuals who had participated in clinical research for subjects who have a close relative with Alzheimer’s disease. Respondents were drawn from studies of healthy individuals who have at least one first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s disease being conducted at four geographically dispersed research centers: Stanford University, Duke University, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Institutes of Health.

All individuals participating in these studies were sent a letter explaining the survey, along with a self-addressed, stamped “opt-out” card. Those who did not return the card within 2 weeks were contacted by telephone. After explanation of the study, those who consented to participate were interviewed by specially trained interviewers from the Center for Survey Research, Boston. Of the 263 eligible respondents, 246 (94%) completed the survey.

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of California, Los Angeles; Stanford University; Duke University; the University of Massachusetts, Boston; and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Survey Development

Following review of the literature, we developed a draft survey instrument that was revised on the basis of input from experts on research ethics and Alzheimer’s disease. The instrument was then administered in person to elderly individuals as a cognitive comprehension and behavioral pretest. The final survey instrument (available from the first author) addressed five domains: 1) clinical research experience, 2) general attitude toward clinical research, 3) attitude toward research advance directives, 4) willingness to participate in clinical research if unable to consent, and 5) sociodemographics.

To assess individuals’ willingness to participate in clinical research if they lost the ability to consent, respondents were asked how likely they would be to give advance permission to be enrolled in five kinds of research: 1) “taking experimental medication that might improve your memory,” 2) “taking experimental medication that would not help you, but might lead to knowledge that would help others,” 3) “answering questions on a computer, if the study could not help you but might lead to knowledge that would help others,” 4) “an Alzheimer study involving two X-rays, if the study could not help you but might lead to knowledge that would help others,” 5) “a study involving two X-rays that would not help you with your Alzheimer’s disease, but could help research on some other disease.”

These examples were chosen to represent the three risk levels included in most proposals: 1) minimal risk, 2) minor increment over minimal risk, and 3) more than a minor increment over minimal risk. The computer study represented a minimal risk study. There is no accepted definition of “minor increment” over minimal risk. In the only article we found on assessments of risk categories, a bone scan was deemed a minor increment over minimal risk by many respondents (22). We assumed that bone scans would be unfamiliar to many of our respondents. Therefore, to represent a minor increment over minimal risk study, we choose a study involving two X-rays, which pose radiation levels roughly similar to a bone scan. The medication study represented a study with more than a minor increment over minimal risk.

Research Advance Directive Development and Administration

Despite discussion of research advance directives, no standard form exists. We developed a draft based on existing clinical advance directives and the proposals for research advance directives (11–17). This draft form was reviewed by experts on research with impaired subjects and revised. At the end of the telephone survey, respondents were told that we would send them a research advance directive within 14 days and that they could return this form to their home research institution using an enclosed self-addressed, stamped envelope. All forms returned to the subjects’ home institutions within 1 year were counted and analyzed for content.

Statistical Analysis

Associations were tested by using a Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for two-by-k tables when the k categories were ordered. Fisher’s exact tests (two-tailed) were used for all two-by-two tables.

Results

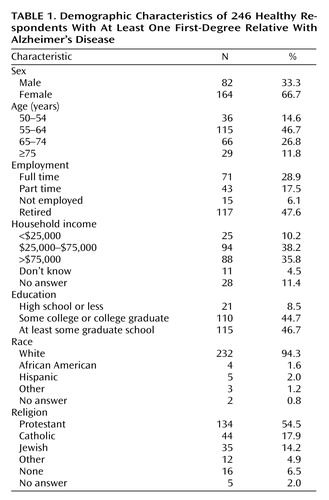

Table 1 indicates respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics. Respondents had significantly higher incomes and more formal education than the average adult living in the United States (23). One hundred thirteen (46%) reported discussing their research preferences with their family.

Willingness to Give Advance Consent

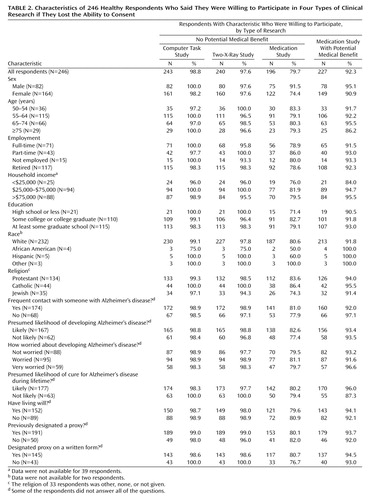

The vast majority of respondents were willing to participate in clinical research if they lost the ability to consent (Table 2). Specifically, 92% were willing to participate in a study that involved taking experimental medication that might help them; 80% were willing to take experimental medication that had no chance of helping them; 99% were willing to participate in a study that involved a computer task that would not help them; and 98% were willing to participate in a study involving two X-rays that would not help them. In addition, 239 (97%) were willing to undergo two X-rays for research on a disease from which they did not suffer (data not shown).

Exploratory analyses revealed no significant associations between individuals’ willingness to participate in these five types of research and their sex, age, employment, income, education, religion, assessment of their chances of developing Alzheimer’s disease, level of worry about Alzheimer’s disease, and previous execution of a clinical advance directive.

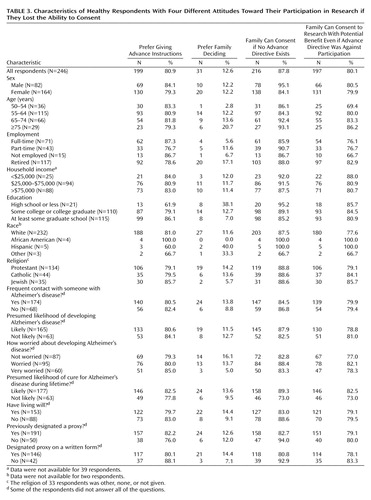

Attitudes Toward Research Advance Directives

Two hundred nineteen respondents (89%) said they were willing to fill out a research advance directive if asked to do so by their family, and 212 (86%) said they would be willing if asked by their doctor. Eighty-one percent said they preferred giving advance instructions rather than allowing their family to make research decisions for them after they had lost the ability to consent (Table 3). Individuals with a college education were significantly more likely than those with a high school education or less to prefer giving advance instructions (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=9.62, df=1, p=0.002); retired individuals were significantly more likely than employed or unemployed subjects to want their families to make research decisions for them if they lost the ability to consent (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=5.58, df=1, p=0.02). Eighty-eight percent stated that their family could enroll them in research in the absence of a research advance directive, and 80% stated that their families could enroll them in potential benefit research even when their advance directive opposed enrollment in research (Table 3). Those who had previously designated a proxy for clinical care were significantly less willing to allow their family to make research decisions for them (p=0.01, Fisher’s exact test).

Completion of Research Advance Directives

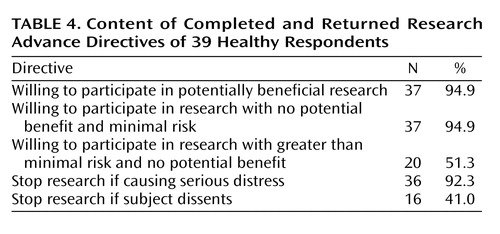

Thirty-nine (16%) of the 246 research advance directive forms were completed and returned to the subject’s home research institution within 1 year (Table 4). Ninety-five percent of the returned forms indicated a willingness to participate in research that offered a potential for medical benefit; 95% indicated a willingness to participate in minimal risk research with no potential for medical benefit; 51% indicated a willingness to participate in greater than minimal risk research with no potential for medical benefit. Ninety-two percent agreed that their research participation should be stopped “at any time it is causing serious distress to me”; 41% agreed it should be stopped “at any time I say I want it to stop.”

Individuals who had discussed their research preferences with their family were significantly more likely to complete and return a research advance directive (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test), as were those who were willing to participate in a medication study that would not help them (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Otherwise, there were no statistically significant associations with sex, age, employment, income, religion, or whether individuals preferred giving advance instructions or allowing their family to decide. None of the 12 nonwhite respondents completed and returned a research advance directive, compared with 17% of the white respondents; this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.22, Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first systematic assessment of individuals’ attitudes toward five of the most prominent proposed safeguards regarding the consent process for research with adults unable to consent. Many respondents said they were willing, if they became impaired, to participate in clinical research that would not help them; only one in seven respondents completed and returned a research advance directive; almost half of all respondents had discussed their research preferences with their family.

Some have argued that enrolling impaired adults in research that offers no compensating potential for medical benefit is inherently exploitative, even when the research cannot be conducted with adults who are able to consent. These arguments assume that enrollment of impaired individuals in research that offers no potential for medical benefit conflicts with their competent preferences—the preferences they had when they were able to understand. Against this, our data suggest that such research may be consistent with the competent preferences of at least some individuals. At the same time, our data cannot be used to estimate how many Americans have this view. Indeed, the majority of Americans may be unwilling to participate in research that offers no potential for medical benefit.

Our data suggest that enrolling adults who are unable to consent in research that offers no potential for medical benefit is not inherently exploitative and, therefore, should not be prohibited altogether. However, the possibility that many individuals may be unwilling to participate in such research suggests that specific individuals should be enrolled only when there is sufficient evidence that enrollment is consistent with their competent preferences.

Several groups would mandate that individuals’ competent preferences must be documented in a formal research advance directive. Although the overwhelming majority of our respondents supported the use of research advance directives, only one in seven completed and returned a research advance directive to their home institution. This failure is striking given that respondents 1) had an overwhelmingly positive attitude toward clinical research, 2) had already enrolled in clinical research on Alzheimer’s disease, 3) were overwhelmingly willing to participate in clinical research if impaired, and 4) recently completed our phone survey, which detailed the difficulties involved in obtaining informed consent from impaired individuals and the ways in which research advance directives could address these difficulties. These factors suggest that the average American is unlikely to be more willing to complete a research advance directive; therefore, requiring that individuals’ competent preferences be documented in a research advance directive could jeopardize important research.

In contrast to individuals’ failure to execute a formal research advance directive, almost half of all respondents reported explicitly discussing their research preferences with their family. Of course, many impaired individuals, especially those unfamiliar with clinical research, may never discuss their research preferences with others. Hence, allowing research enrollment of impaired adults on the basis of sufficient evidence of their competent preferences, without stipulating how such evidence must be documented, will not ensure that all impaired individuals who wanted to enroll in clinical research will be able to do so. Nonetheless, our data suggest that this approach is more likely to lead to research decisions consistent with individuals’ competent preferences.

Some have argued that only individuals who have been formally assigned to serve as a research proxy should be able to enroll impaired adults in clinical research. Against this, 88% of our respondents supported allowing their families to make research decisions for them. In contrast, respondents who had assigned someone to make clinical decisions were overwhelmingly willing to participate in research once impaired, but they were unwilling to allow their families to make research decisions for them. Although not supported directly by our data, these facts suggest that individuals who have assigned someone to make clinical decisions for them if they lose the ability to consent prefer having these individuals make their research decisions as well.

One possibility would be to incorporate statements about individuals’ research preferences on clinical advance directives. For instance, individuals could be asked to specify whether the person they assign to make clinical decisions for them should be allowed to make research decisions as well. Including statements about research participation on clinical advance directives might also prompt individuals to discuss their research preferences with their proxies and families, thus increasing knowledge of individuals’ competent research preferences.

The possible limitations of relying exclusively on individuals’ preferences as specified in formal advance directives are highlighted by the fact that 80% of our respondents would allow their families to enroll them in research that offers a potential for medical benefit even when their advance directive opposed research participation. This finding suggests that competent preferences expressed in formal research advance directives should not automatically be regarded as definitive. Instead, these expressions should be evaluated in the context of any other evidence of individuals’ competent preferences, such as discussions with family members, as well as other reasons (e.g., the study offers potential medical benefit) to think the individual would or would not want to be enrolled in the study in question.

A number of proposals would prohibit the enrollment of impaired adults in research on conditions from which they do not suffer. However, almost identical numbers of respondents were willing to participate in two-X-ray studies on conditions from which they suffered and two-X-ray studies on other conditions (98% versus 97%). This suggests that, for the purposes of deciding whether they are willing to be enrolled in clinical research once impaired, many individuals may not be concerned primarily with the condition being studied. Instead, many individuals may base these decisions on the risks and potential benefits that the research offers to them, as well as the extent to which their research participation may help others.

There is widespread agreement that impaired individuals should be removed from clinical research if they object. Surprisingly, half of all the respondents who returned a research advance directive stated that their research participation should not be stopped if, once impaired, they say they want it stopped.

This finding should be evaluated with caution. Less than one in seven respondents returned a research advance directive. Moreover, these individuals may have been concerned that a single objection would eliminate them from potentially beneficial research. In addition, respondents may not have fully appreciated subjects’ rights to withdraw from clinical research. Nonetheless, these data appear to contradict proposals that would remove impaired adults from research at the first sign of dissent. One possibility would be to halt temporarily and obtain an independent assessment of the research participation of impaired adults who object. While this approach is more likely to respect individuals’ competent preferences, the principle of beneficence suggests that the sustained objections of impaired individuals should be respected irrespective of their competent preferences.

The present data are subject to several important limitations. First, as with any initial study, further research will be needed to assess whether the current findings generalize to other populations. In particular, it will be important to assess whether individuals at risk for other disabling conditions, such as schizophrenia and stroke, have similar attitudes. In addition, since we surveyed individuals older than 50 years of age, some of our results may be due to a generational effect. Although we did not find any statistically significant effects based on race, they may be seen in future studies that include more minority subjects.

We assessed the execution rate of research advance directives by sending individuals a form and asking them to fill it out. Future research should consider whether more active approaches, such as intervention by personal physicians, might result in higher execution rates. Finally, the percentage of individuals willing to participate in no-benefit research was lower among those who completed and returned a research advance directive than among all those who participated in the telephone interview. In the light of the very low return rate for the advance directives, future research should assess whether this is a statistical artifact or whether individuals who complete a research advance directive are less willing to participate in no-benefit research.

|

|

|

|

Received June 6, 2001; revision received Oct. 18, 2001; accepted Nov. 27, 2001. From the Department of Clinical Bioethics, National Institutes of Health; the Geriatric Psychiatry Branch, NIMH, Bethesda, Md.; and the Center for Research Methodology and Biometrics, AMC Cancer Research Center, Denver. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wendler, Department of Clinical Bioethics, Warren G. Magnuson Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bldg. 10, Rm. 1C118, Bethesda, MD 20892-1156; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank their collaborators: Gary Small, Andrea Kaplan, and Karen Miller at the University of California, Los Angeles; Ranga Krishnan, Murali Doraiswamy, and Jessica Sylvester at Duke University; Jerome Yesavage and Cathy Fenn at Stanford University; and Judy Friz and Sue Bell at NIMH. They also thank Frank Miller, Alan Fleischman, Brian Clarridge, Patricia Backlar, Rebecca Dresser, Kiran Prasad, and Marion Danis. The ideas and opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not represent any position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service, or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1. Childress J: The place of autonomy in bioethics. Hastings Cent Rep 1984; 14:12-16Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Dworkin G: The Theory and Practice of Autonomy. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1988Google Scholar

3. Beauchamp TL, Childress J: The Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 77-104Google Scholar

4. Veatch RM: From Nuremberg through the 1990s: the priority of autonomy, in The Ethics of Research Involving Human Subjects: Facing the 21st century. Edited by Vanderpool HY. Frederick, Md, University Publishing Group, 1996, pp 45-58Google Scholar

5. Bonnie RJ: Research with cognitively impaired subjects: unfinished business in the regulation of human research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:105-111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Capron AM: Incapacitated research. Hastings Cent Rep 1997; 27:25-27Google Scholar

7. American College of Physicians: Cognitively impaired subjects. Ann Intern Med 1989; 111:843-848Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Appelbaum PS: Patient’s competence to consent to neurobiological research. Account Res 1996; 4:241-251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Appelbaum PS: Rethinking the conduct of psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:117-119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Berg JW: Legal and ethical complexities of consent with cognitively impaired research subjects: proposed guidelines. J Law Med Ethics 1996; 24:18-35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Dresser R: Mentally disabled research subjects: the enduring policy issues. JAMA 1996; 276:67-72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Keyserlingk EW, Glass K, Kogan S, Gauthier S: Proposed guidelines for the participation of persons with dementia as research subjects. Perspect Biol Med 1995; 38:319-361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Melnick VL, Dubler NN, Weisbard A, Butler R: Clinical research on senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: suggested guidelines addressing ethical and legal issues, in Alzheimer’s Dementia: Dilemmas in Clinical Research. Edited by Melnick VL, Dubler NN. Clifton, NJ, Humana Press, 1985, pp 295-308Google Scholar

14. Moorehouse A, Weisstub DN: Advance directives for research: ethical problems and responses. Int J Law Psychiatry 1996; 19:107-141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. National Bioethics Advisory Commission: Final Report: Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity. Springfield, Va, US Department of Commerce, Technology Administration, National Technical Information Service, Dec 1998Google Scholar

16. New York State Advisory Work Group on Human Subject Research Involving Protected Classes: Recommendations on the Oversight of Human Subjects Research Involving the Protected Classes. Albany, State of New York Department of Health, 1998Google Scholar

17. Attorney General’s Working Group: Final Report of the State of Maryland Attorney General’s Working Group on Research Involving Decisionally Incapacitated Subjects. Annapolis, Md, Attorney General’s Office, June 12, 1998Google Scholar

18. National Institutes of Health: Interim research involving individuals with questionable capacity to consent: points to consider. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:1013-1016Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. SUPPORT Principal Investigators: A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA 1995; 274:1591-1598; correction, 1996; 275:1232Google Scholar

20. Emanuel LL, Barry MJ, Stoeckle JD: Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:889-895Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Gross MD: What do patients express as their preferences in advance directives? Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:363-365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Janofsky J, Starfield B: Assessment of risk in research on children. J Pediatr 1981; 98:842-846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. US Census Bureau: Educational Attainment in the United States, March 1999: Detailed Tables. http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/education/p20-528.htmlGoogle Scholar